Throughout the Second World War the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) sent out mobile field units to record audio for radio broadcast.

Throughout the Second World War the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) sent out mobile field units to record audio for radio broadcast. The first unit arrived in the Middle East in October 1940, equipped with a large studio truck and a utility vehicle with portable recording equipment, to be operated by technicians of the Postmaster-General’s Department. The unit recorded actualities, reports, and descriptions of the situation at the front, as well as interviews with members of the forces and hundreds of messages home for the Voices from Overseas program.

“Making recordings for broadcasting is a fairly simple matter if you’re working with recording gear set up on a bench in a well-lit studio, but it’s quite another matter when you try to make a recording in a dug out, in the back of a truck, or the floor of a tent with a sandstorm raging outside and the dust filling the grooves of the discs as soon as they have been cut.”

Lawrence H Cecil, ABC Field Unit

Recordings were cut into lacquer discs (also known as acetate discs) using a portable disc-cutting lathe that was both cumbersome and delicate. Lacquer discs have rigid cores of metal (or occasionally glass or cardboard, due to wartime metal shortages) with a surface coating of nitrate cellulose lacquer. A sapphire cutting head on the lathe moved in sync with the electrical current coming from the microphone, through the amplifier, cutting a groove into the record’s lacquer surface.

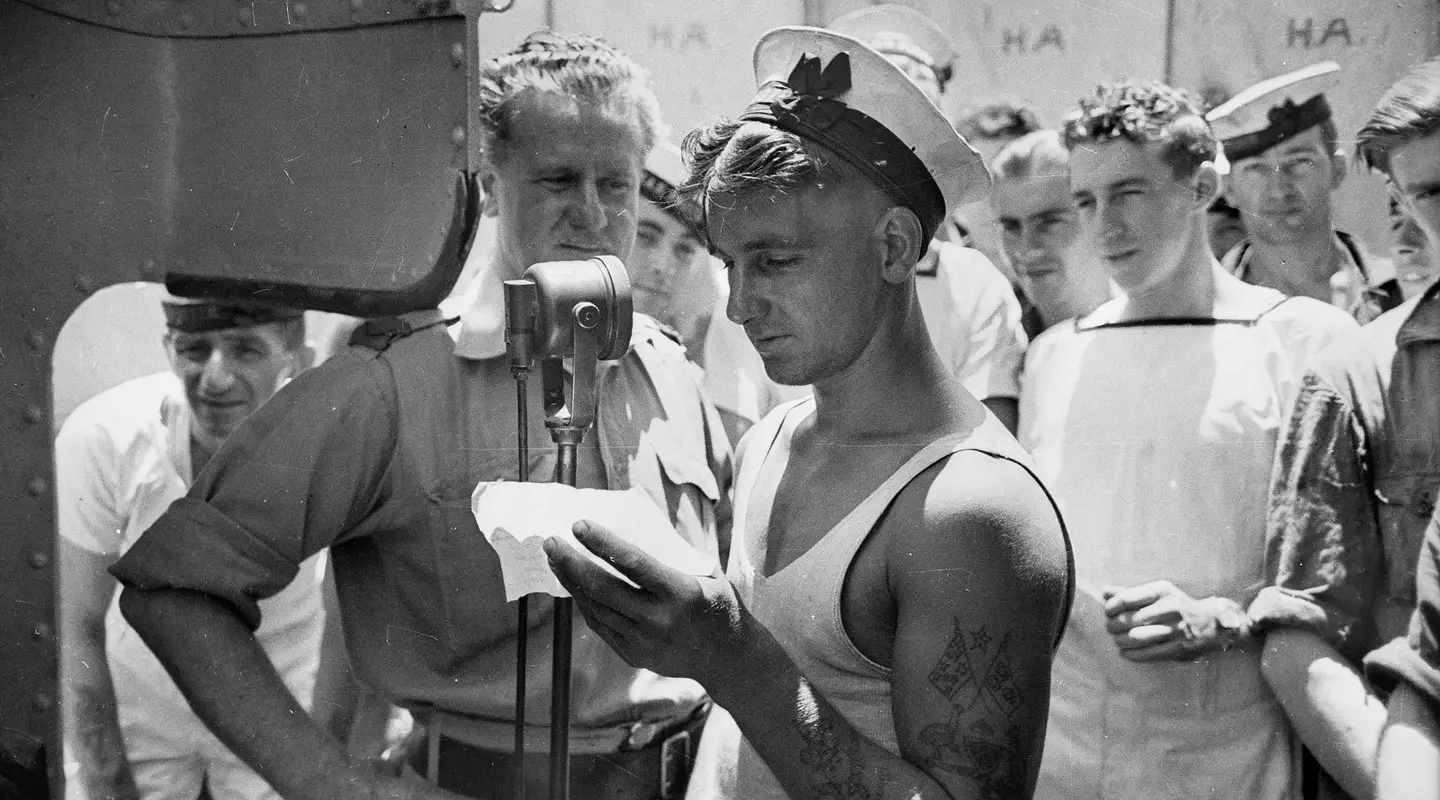

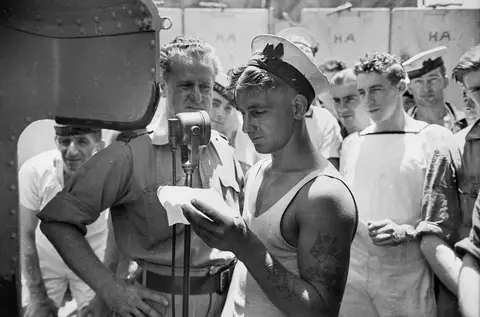

Lawrence H. Cecil of the ABC, recording messages home on board HMAS Perth, 1941. Photographer George Silk.

In a snowy region near Salonika in Greece, ABC correspondent Chester Wilmot recollected, “The cold made the acetate discs so hard that the recordings couldn’t be cut, until [sound engineer] Bill MacFarlane warmed them up by holding them close to his chest under his great coat. And when the road was blown about 2am, the explosions shook the truck and the cutting head momentarily lifted, but the recording was playable.”

There were similar problems on the bridge of HMAS Perth during an air raid in Alexandria: every time Perth's guns fired, the cutting head lifted, leaving only snatches of sound in the recording. At Tobruk, a nearby Vickers gun caused the cutting head to skip with every burst of rounds.

Later in the war other ABC units used the equipment around the Pacific and in Australia, on board ships and motor launches, in the air, and from the backs of vehicles. Unlike the problems of recording in the snow, the heat in this region softened the lacquer discs, so a clean cut of broadcast quality could not be achieved. The solution was to record in the relative cool of early morning or evening.

ABC records messages home

[Singing] The more we get together, together, together

The more we are together the happier we'll be

Cause your friends are my friends

And my friends are your friends

Alright boys, alright, and you're all my friends don't forget that. All right I want you to be quiet because we're going to start the voices now. Standby for we're recording in 10 seconds from now.

Best of health and spirits to everyone as [unintelligible] Cheerio and keep smiling.

My that sounds good, best of health and spirits in the bottle.

Hello Australia, this is Jimmy [unintelligible] with a cheerio call from the Middle East. To my brother Syd and Nancy, and her mother Sue. I am in the best of health and hope all at home are OK. Cheerio to call to all [unintelligible] and personnel and hope to be home shortly. Love to all at home from Jimmy. Popeye sends a cheerio call to Charlie Badden of [unintelligible] and wish him a speedy recovery.

Righto, I say Popeye when you going to join the Australian Forces? Very shortly. Very shortly - you belong the [unintelligible] You look just splendid in that uniform! laughs It's not all in keeping though.

Calling Turramurra this is Jack McCurren speaking from somewhere in Lebanon. It's a great day here and the boys are in the best of spirits. Hello dearest aunty and Joyce, uncle Jack and Norman. How is [unintelligible]? As far I know Fred and Tom is doing fine, although I haven't seen him in the last days, love to Mrs Murdoch and Nan, Vauxhall and Valentine families, Jimmy and Mrs Burke, Captain [unintelligible] Naomi and all my good [unintelligible] in Sydney and Brisbane. We've had a great time in Syria but we'd sure like to see the Harbour bridge again. Love to you all and I hope to be home soon.

My word Sergeant you've saved a few stamps on that one, didn't you? You reckon? My well I do.

Hello Sydney, this is Jack Roberton, sending a cheerio call from Syria to mother and family at Bondi Junction. And also daughter Shirley, Mr and Mrs Marshall of Manly. All OK, having a great time. Wish to be remembered to all friends. Aussie girls and aussie beer is still our favourite. Cheerio and hope to be home soon. Good luck and keep your chin up. Known through the Middle East as 'Honest John' - rather amusing to the boys of Bondi Junction and I've only got one red mark on my paybook. laughs

Good boy honest John, why do they call you honest John?

Well, I was always known for the square deal I give everyone.

And what about all those girls at Bondi Junction? Do they call you honest John?

Well, just tell them to forget about me. laughs

NSW this is a great day. We've got with me my good [audio ends]

Over New Guinea, correspondent Frederick Simpson and technical officer Len Edwards used equipment modified by Edwards which allowed them to record in an airborne Liberator bomber. To record Zebu oxen on the move in Malaya, Edwards placed the disc cutting equipment in a slow-moving jeep as Simpson walked between the herd and the jeep with the microphone.

Towards the end of the war, some ABC recordists started using a smaller wire recorder. This new equipment recorded audio magnetically onto a spool of thin wire; this had a recording duration of two hours and the ability to delete and re-record. The thin wire did, however, have a nasty habit of snapping and unspooling.

How Recordings were made and Despatched during the Libyan Campaign, part 1/4

During the Libyan Campaign, the Australian Broadcasting Commission's Field Unit with the AIF had to write its script to make its recordings when and where it could. In this story the CO of the unit, Lawrence H. Cecil, tells us some of the strange places in which these were done.

Making recording for broadcasting is a fairly simple matter if you're working with recording gear set up on a bench in a well-lit studio. But it's quite another matter when you try to make a recording in a dugout, in the back of a truck, or the floor of a tent with a sandstorm raging outside and the dust filling the grooves of the disc as soon as they have been cut. In conditions like these we made a recording of Christmas greetings from the most advanced Australian troops near Mersa Matruh last December. I had twenty-six men in a small dugout which was normally the Sergeants mess. The dugout was about 12 feet by 24 [feet] and so you could imagine a couple of dozen voices in that confined space was a problem in acoustics that I had difficulty in solving. Whilst Bill McFarlane our engineer, outside in the driving sandstorm was endeavoring to shield the equipment which was set up in the utility truck. After cutting the first record he asked me to spare if he could move the gear into an adjacent tent. With much willing help we struggled with the blinding sand and set up in the tent. But this was worse. Everything covered over almost as fast as it could be dusted off and so we were forced to bring everything back again to the truck, which was a little more protected than the tent. But unfortunately, it was made unstable by the wind and this swaying added to the problem. Nevertheless, we persevered, recording five sides with only one recut. At the finish Bill, was covered in sand and looked as though suffering from yellow jaundice, but I assure you it was only his appearance that was yellow for he did a good job under difficult conditions.

Outside Bardia our recording studio was a cave, situated in a wadi running up from the escarpment and Sallum. The small harbour had been visited by the "Flying Circus" and had been bombed several times. So, we set up the gear in anticipation, ready to jump into action recording a bomb-to-bomb description. The "Flying Circus" consisted generally of about half a dozen bombers, chaperoned by a large number of fighters. But every day we were set up ready, these bombers and fighters stayed away. Recording battle actualities may be compared with fishing, luck and opportunity are important factors. Days go by and nothing happens then suddenly perhaps everything is occuring all over the place at the same time making it impossible to cope with. Or having waited in vain and moved to another position is made, making the thing you had wanted happens in the place you had left.

After the gear had stood ready for action for a few days and nights with nothing happening, we learned of a special bombardment that was to take place. So packed the gear and went expectedly to the front line and waiting all night on the plateau. But the shoot was cancelled and so we had the disappointment of returning without a recording. We came down the Sallum escarpment, passed the harbour, along the track to our cave in the wadi when suddenly CRUMP CRUMP CRUMP behind us on the harbour fell three huge bombs from the "Flying Circus". We jumped out of the truck, and there almost above us were five bombers and thirty-one fighters. And on the breakwater and in the town were huge clumps of black smoke curling up from the road we had just left. Besides dropping bombs in Sallum, and on the shipping in the bay, they combined the raid with spotting for their 6 inch battery in Bardia, which fired three salvos. The crump of the shells exploding, mingled with the bursting of huge bombs and the shellfire from our anti-aircraft guns dotting the sky, made an inferno in sound of which combination we will probably not get again. And then came in sight six of our Gladiators, twenty-four of the Italian escort disengaged to give fight, whilst the other seven and the bombers made off to safety.

Fight did I say? In less than ten minutes there was not an Italian plane to be seen. A couple of losses and the remainder flew away as fast as they could go.

And during all this marvelous display - this broadcasters dream - our gear was packed in the truck and it was all over before we could get into action.

Chester Wilmot and I looked at each other broken-hearted. And from each came the same remark: wouldn't it? Just wouldn't it?

Narrated by Lawrence H. Cecil and introduced by Chester Wilmot.