By his own account a genius, was Hitler chiefly responsible for Nazi Germany's military defeat?

In the early stages of the Second World War, as victory followed victory for the Germans, it became common among Nazis to refer to Hitler as the Grösster Feldherr aller Zeuten, the "greatest military commander of all time”. Later on, as victory turned to defeat, the sobriquet was abbreviated to Gröfaz and acquired an ironic, derogatory flavour in the mouths of the ordinary German troops who had to pay the price. Which use of the term was the more appropriate? Was Hitler a military genius? Or was he, as many of his generals claimed after the war, an incompetent, untrained in matters of strategy, ignorant of military doctrine, and unwilling to take their informed and invariably sensible advice?

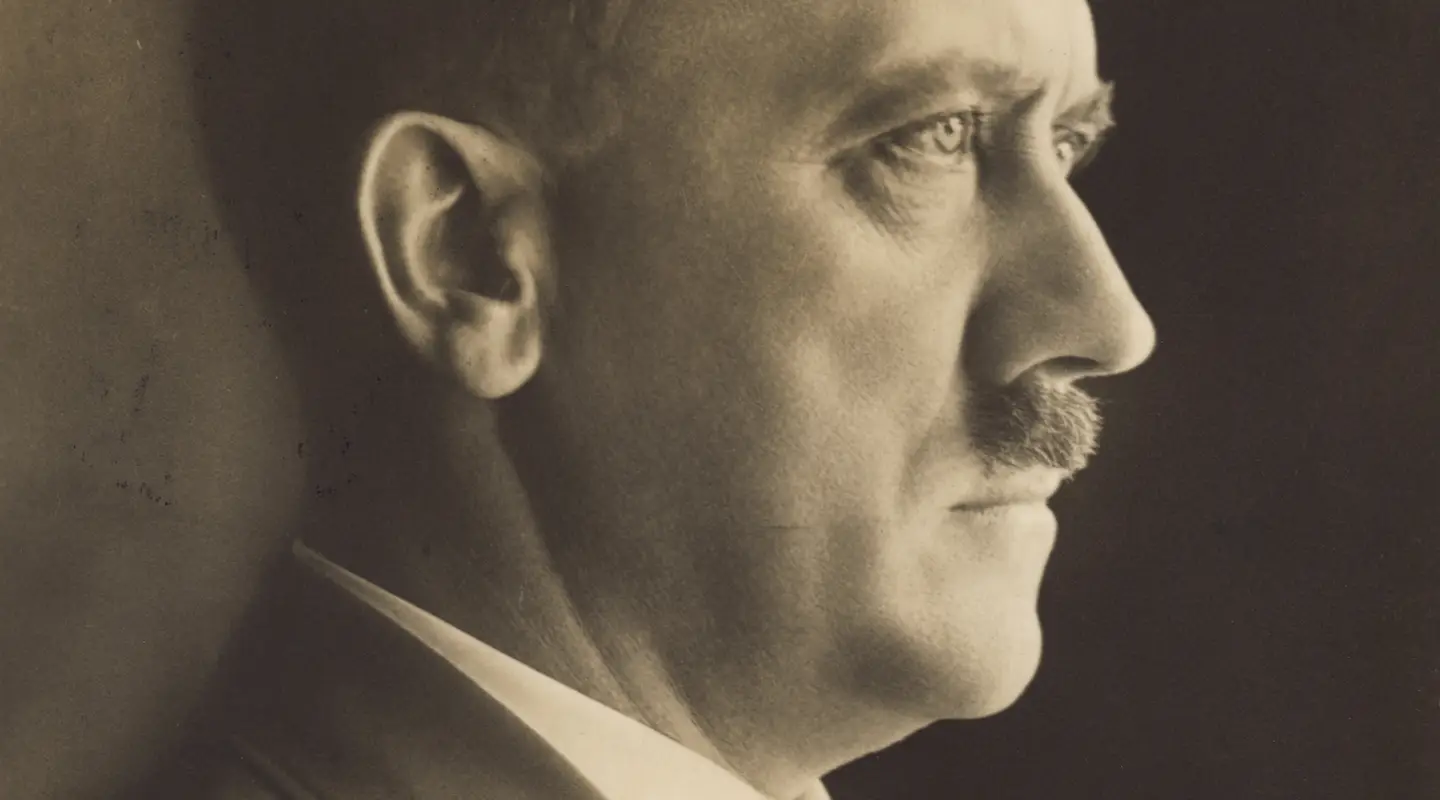

Adolf Hitler in 1939. Photographer: Heinrich Hoffmann

Hitler had fought in the First World War, but as an ordinary soldier, not as an officer. He had no military experience beyond that of a front-line messenger. A charismatic politician, he led the Nazi Party to a series of stunning election successes in the economic depression of the early 1930s and was appointed as head of a coalition government by the Weimar Republic’s aged President, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, on 30 January 1933. Outmanoeuvring his conservative coalition partners in the cabinet, and unleashing a storm of retrospectively legalised violence on the streets, he succeeded in establishing a one-party dictatorship by July 1933, and became head of state, or “Leader” (Führer), on Hindenburg’s death the following year.

Hitler intended from the very beginning to wage another European war in order to regain the territories Germany had lost after her defeat in 1918. He wanted to resume the drive to conquer large swathes of territory in the east that had met with temporary success in 1917–18 after the Bolshevik Revolution had taken Russia out of the war.

On 3 February 1933, anxious to secure the support of the Reichswehr, the small but well-disciplined army of the Weimar Republic, he told its senior officers – all of whom had received their training under the Kaiser and remained wedded to traditional military doctrines and ambitions – that he would restore conscription, revise the Treaty of Versailles, and “Germanise” eastern Europe.

Soon he had sidelined those officers skeptical of Nazism and was pressing the army leadership for estimates of what it would cost to rearm. Their initial figures he rejected as too modest. By 1937 rearmament was in full swing, but the senior officers were still in his view too cautious; so he now manoeuvred some 60 of them into resignation, premature retirement, or redeployment by one means or another, and appointed himself supreme commander of the armed forces early in 1938.

From now on, he had complete control. But the remaining senior generals still considered Hitler’s headlong rush to war premature, and Germany’s prospects in a general European war dismal in the extreme. During the Munich crisis of 1938 they planned to arrest him, before the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain pulled the rug from under them by forcing Czechoslovakia to yield to Germany’s territorial demands. So by the time it came to the invasion of Poland in September 1939, Hitler had ample experience of what he considered to be the excessive caution and lack of ambition of the senior German generals.

Triumph and Temptation

Hitler’s foreign policy successes in 1938–39, the easy conquest of Poland, and above all the rapid defeat of France, Holland, Belgium, Denmark and Norway in 1940, silenced his remaining critics in the top ranks of the army. True, it was his order that had halted the German troops shortly before they reached the Channel in 1940, allowing the British to evacuate their forces successfully from Dunkirk. But the German armies were halted on the advice of a senior general, Gerd von Rundstedt, who thought that the troops needed a break before turning south towards Paris – and of Hermann Göring, who assured him that his air force could destroy the British on the beaches.

German troops on the outskirts of Warsaw, Poland, September 1939. The stunning success of the Wehrmacht in Poland in 1939, then France in 1940, silenced Hitler’s remaining critics in the top ranks of the army.

Despite the failure to conquer Britain, the German generals regarded Hitler by this time as little short of a genius, and accepted his assurances that the Soviet Union, his next target, would crumble easily. On 22 June 1941 the largest invasion force in history marched eastwards into Soviet territory. The Germans and their allies scored a series of stunning victories, encircling and destroying a series of huge Red Army forces and taking millions of prisoners (3.3 million of whom they deliberately left to starve to death or perish from disease in makeshift camps in the open). But within a relatively short period, the generals running Operation Barbarossa were privately recording their consternation at the refusal of the Soviet armies to give up. They were losing large quantities of men and equipment as the Red Army brought in seemingly limitless numbers of fresh reinforcements. At the end of July 1941 the generals paused the invasion to recover and regroup.

The invading force was divided into three army groups – north, centre and south – and Hitler now ordered the southern group to be strengthened with troops taken from Army Group Centre and to conquer Kyiv and southern Ukraine, securing the vast grain fields and industrial resources of the region and marching towards the oilfields of the Caucasus. The commander of Army Group Centre, Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, objected: Prussian military doctrine dictated the prime objective of a campaign to be the destruction of the enemy’s main force, and this, he told Hitler, lay before him, outside Moscow. Whatever its economic justification, the attack on southern Ukraine was, he said, a “sideshow”. The German forces in Ukraine won another series of spectacular victories, and troops and equipment were sent back to Army Group Centre to resume the march on Moscow.

But the delay was fatal. After getting bogged down in the autumn mud, the German troops were attacked by fresh Soviet reinforcements brought in from the Pacific coast, where it was clear from mid October that the Japanese intended to push south in the Pacific instead of west into Siberia. Dressed only in light uniforms, the German forces began to freeze to death in the winter snows. The offensive shuddered to a halt. The generals had persisted in their rigid devotion to attack, they had failed to prepare defensive positions for overwintering, and they were paralysed by indecision as the failure of Operation Barbarossa became evident.

Hitler signs an autograph for a young boy. Germany c. 1933

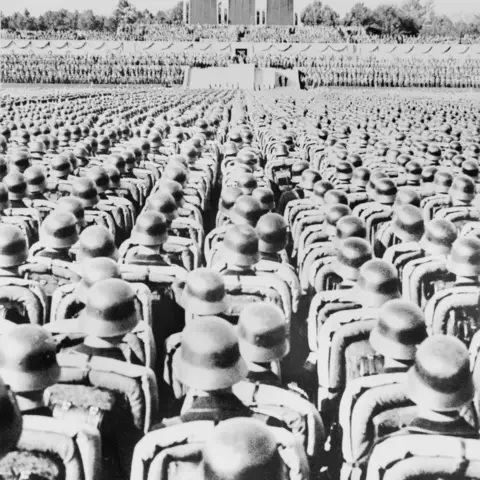

Hitler appointed himself supreme commander of the armed forces in early 1938. Here, he addresses troops at the 1938 Nuremberg Rally.

In this situation, the generals cracked; three of them suffered heart attacks, and Bock himself went on sick leave. Those who remained looked to Hitler to deal with the catastrophe. He issued orders to stand firm, a decision greeted with relief by most senior officers. Those who carried out tactical withdrawals, like the tank commander Heinz Guderian, were dismissed. Hitler blamed the defeat before Moscow on the indecision of the generals. From now on he regarded them with increasing contempt. In the new year, when Bock returned from sick leave to take charge of Army Group South, he captured the city of Voronezh but, aware that his troops were exhausted after a lengthy campaign in the Crimea, he refused to move on to encircle the retreating Soviet divisions. Hitler regarded him as overcautious and fired him.

Stalingrad and the Caucasus

Moving his field headquarters to Vinnitsa, in Ukraine, Hitler took over operational command himself, splitting Army Group South in two, with the northern divisions marching on Stalingrad and the southern into the Caucasus. Both forces scored significant victories, but they were also weakened by the diversion of troops to take part in the siege of Leningrad (now St Petersburg). Every time the Red Army counter-attacked, Hitler refused the generals permission to carry out a strategic withdrawal to stronger defensive positions. “You always come here with the same proposal,” he shouted at the army chief, Franz von Halder, “that of withdrawal.” Halder in his turn was dismissed by the dictator, who accused him of losing his nerve.

Spread too thinly, the German armies ran into tough resistance from the Soviet forces. Though its strategic significance was debatable, the city of Stalingrad on the Volga held a special significance for Hitler because it was named after the Soviet dictator. Despite taking most of the city, the German, Italian and Romanian forces were surrounded by the Red Army in a vast pincer movement stretching across hundreds of kilometres. The general in charge of the German forces, Friedrich Paulus, did not organise a breakout and retreat because he knew Hitler would countermand the order. By the end of the year the German armies’ supplies were cut off as the Soviet forces pressed ever closer. The troops began to starve to death. Without sufficient fuel a breakout was now in any case impossible.

At the beginning of February Paulus surrendered, refusing the command to kill himself which Hitler had implied with his promotion to Field Marshal. Even Hitler could recognise that defeat at Stalingrad left the German forces in the Caucasus in danger of being cut off, and agreed to a retreat: shortly after having given his assent, he changed his mind, but the order had already been given and the German forces withdrew. By the time the spring rains came, the Eastern Front had been stabilised for the moment.

A German self-propelled howitzer on the Eastern Front. Germany’s generals had accepted Hitler’s assurances that the Soviet Union would crumble easily. This was not to be.

This was one of a number of occasions on which Hitler accepted the necessity for a tactical withdrawal. He could also be persuaded to bow to the conditions imposed by the weather, delaying the assault on France in 1939–40 until the ground was firm enough to bear the weight of the armour which was the most important element in the attack, or ordering a pause in troop movements in the sodden spring of 1943. But on the whole he regarded such standard military manoeuvres as little more than evidence of cowardice on the part of those who advocated them. The more difficult the situation became, the more reluctant he was to take advice from the professionals.

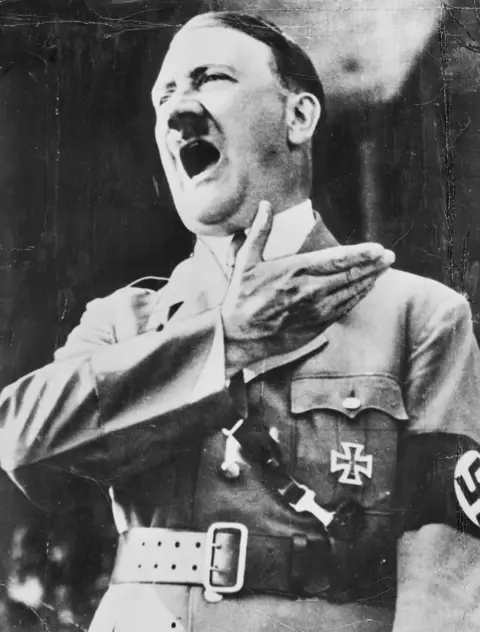

For Hitler, the most important aspect of waging war was will power. The German troops in the First World War, he believed, had in the end lacked the will to carry on, undermined by traitors behind the front. His own triumph in 1933 had been, as Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda film put it, a Triumph of the will; his iron will power had overcome the obstacles set in his path by conservative and unadventurous generals in 1938 and had achieved the rapid victory over France that brought those generals unconditionally behind him.

Hitler was confirmed in his growing contempt for the traditionally trained military elite of Germany by their repeated warnings about the strength of their Soviet enemy, by their appeal to his leadership during the crisis before Moscow, and now, in the spring of 1943, by their vacillations and disputes over the best way forward. Should they try to hold the line in the east while strengthening the Reich’s defences in Italy and the west? Or should they attempt to regain the initiative in the east by a bold and aggressive stroke against “the Russian” or “Ivan”, as the Red Army was generally known? Inevitably, Hitler chose the latter course. The generals argued about where the attack should fall. Hitler decided on a massive assault against an exposed salient in the Soviet front line at Kursk, spearheaded by armoured divisions. But the Soviet generals got wind of this early on, and prepared defences in depth, assembling more than four million troops and huge quantities of armour and combat aircraft, vastly outnumbering the Germans in every respect. As the assault ground to a halt in mid-July, Hitler ordered his tank divisions to redeploy to Italy, where the Allies had landed in Sicily on the 10th. From this point on the story of the German armed forces in every theatre of war is a story of more or less continual retreat.

For Hitler, and for the Nazis more generally, there was no question of bringing the conflict to an end by suing for peace in the face of what was increasingly recognised as the inevitability, sooner or later, of defeat. Hitler believed that only through perpetual warfare, conflict, struggle, in adversity as well as in victory, could a people be hardened, their will strengthened, their ultimate triumph secured. War was an end in itself, not a means to an end; had he won in Europe, there is every indication, following suggestions he made in his unpublished “second book” in 1928, that Hitler would have unleashed a war against America. “I always go for broke,” he once said: compromise was not in his nature. In any case, the Allies insisted from early 1943 onwards that nothing short of an unconditional German surrender would bring the war to an end. There was, therefore, no real choice that Hitler had to face.

In the months following the battle of Kursk the German armies, heavily outnumbered and heavily outgunned, were forced time and again to retreat. On every occasion Hitler ordered them to stand firm. Frequently his orders were simply disregarded – among others, by one of his most favoured generals, Walter Model, who was not prepared to sacrifice his troops in a futile defence action when manpower was becoming so scarce. Hitler sacked General Werner Kempf for ordering the evacuation of Kharkov before it was completely surrounded by superior Soviet forces, but Kempf’s replacement told him that there was no alternative, and so, reluctantly, Hitler approved the retreat. But as the Red Army approached and then entered Germany he was prepared to endorse only resistance to the bitter end.

Collapse and defeat

Making a speech in 1940. Hitler believed many of his generals lacked will power, which he considered the most important aspect of waging war.

Hitler was in the end no more incompetent in most respects than the vast majority of the military professionals who served him, and their postwar attempts at self-justification carried little conviction. They frequently vacillated and dithered, and they were in such awe of him that they surrendered much of their own judgement to the power of his will. More tactical flexibility of the kind Hitler hated would have saved many lives but it would not in the end have changed very much. In one respect, however, Hitler was markedly inferior to them, and that was in his ability to bolster the morale of the troops and civilians he led.

As the situation got worse, he hid himself away from the population at large, refused to acknowledge – let alone share in – in their sufferings, and increasingly voiced his contempt for their weakness and his conviction that they deserved to perish. Nazism in its final phase relied on terror to keep people going. And if military leadership also involves a concern for the conquered, Hitler failed here too: his savage and genocidal treatment of “Slavs” in the occupied territories convinced the citizens and soldiers of the Soviet Union that however bad a life under Stalin might be, it was at least a life; while the extermination of six million Jews brought the Western Allies to the conviction by December 1942 that Nazism embodied the ultimate evil. Already in 1943 German military communications were becoming seriously disrupted as men flocked to join partisan units, Jewish and non-Jewish, in the east and, in the last year of the war, resistance movements in the west.

In the last months of the war, Hitler’s mistrust of the military was deepened by the involvement of a number of army officers in an attempted military coup, following the attempt to assassinate him on 20 July 1944. And as the military situation worsened, he dismissed one general after another for incompetence or cowardice. Typically, his reaction to the D-Day landings in June 1944, and the Allied advance across northern France and southern Belgium, was to order a fresh attack, seeking to replicate the triumphs of 1940. He expected the Americans, whom he regarded with almost as much contempt as “the Russian”, to crumble. But in the battle of the Bulge at the end of 1944 they eventually held firm. By this time manpower and supplies of matériel and fuel were becoming woefully short.

As the Allies advanced from the west, south and east, Hitler lost touch with reality, hoping for the advent of “wonder-weapons” that never came or – if, like the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 rocket, they did come – were too few in number and too hastily produced to be effective. By the final stage of his dictatorship he was ordering about divisions that no longer existed except on paper.

Finally accepting that he was defeated, he committed suicide along with his long-term companion (now, at the end, his wife) Eva Braun, on 30 April 1945. Large numbers of army officers and Nazi administrators followed him into oblivion, unable to conceive of a future beyond the Third Reich.