Letters to a model reveal wartime longing, connection and a life cut tragically short.

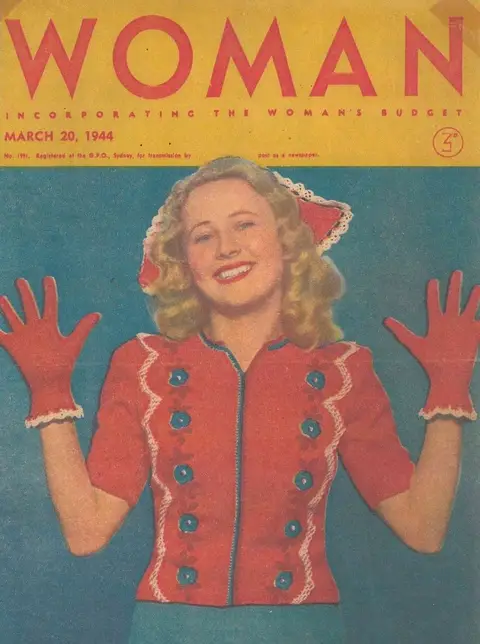

When Astrid Wagstaff appeared on the cover of Woman magazine in March 1944, her golden curls and bright blue eyes lit up newsstands across Australia. Just nineteen years old, the Sydney stenographer dreamed of becoming an actress, but her cover debut unexpectedly made her a wartime icon. For servicemen stationed around the world, Astrid’s image was more than a pretty face. She was a reminder of home, and a fleeting sense of normal life amid the uncertainty of war.

Letters soon began to arrive from soldiers touched by her warmth and innocence. No one could have guessed that Astrid’s life would end just two years later in a tragic accident.

Astrid Wagstaff dreamed of becoming an actress. Photo courtesy of Hilary Cleland.

The collection of letters written to her was later donated to the Australian War Memorial by her niece, Hilary Cleland.

“I found the letters once my grandmother and mother had passed away,” she said.

Hilary, the daughter of Astrid’s sister Dahlas, grew up hearing stories about her aunt.

“I never got the chance to meet Astrid, but she was always described as very sweet. She was also a very talented artist who kept a sketchbook of drawings – she had a very good eye.”

Astrid on the cover of Woman magazine, March 1944. Courtesy of Hilary Cleland.

Cover girl

Astrid Volga Wagstaff was born in Chatswood, NSW, on 17 November 1925, the youngest of three daughters born to First World War veteran Robert and his wife Eva.

The years during the Second World War were lively in the Wagstaff household. Astrid modelled, wrote letters to men of the Merchant Navy and helped her mother host Sunday lunches for local and visiting servicemen – dishing up roast dinners and custard to packed tables.

“Every Sunday lunchtime the house would be full, and the boys would flock in” Hilary said.

Astrid’s father would joke that the home was like “flies to honey” with three daughters in residence, who could “stop the carriages at Chatswood Station” with their beauty.

One serviceman even confirms as much, writing:

“I was wondering where I had seen you before … I happened to see you on Chatswood Station”

Letters from the Front

Within weeks of the magazines release, Astrid began receiving letters from servicemen around the world – from nearby bases to the islands of the Pacific and the front lines of Europe. The letters expressed a wide range of emotion, from playful flirtation to genuine connection and friendship.

Fan mail to Astrid from a U.S Serviceman. AWM2025.6.56-14

One serviceman confessed:

“I’m just scribbling these few lines in appreciation of this photograph, which I must say is very nice and now has priority IA in our tent ‘pin ups'."

A US serviceman, Gene, boldly declared:

”A few days ago, I chanced to see your picture on the front of Woman magazine. Your picture impressed me very much and I said to myself, ‘there’s a girl I would really like to know."

Sergeant Reginald Lee of the RAAF discovered Astrid’s photograph under unusual circumstances. While walking along a beach in Papua New Guinea, he came across the wreckage of a crashed aircraft.

“My curiosity got the better of me so I proceeded inside to do a little snooping," he wrote.

Inside, he discovered a copy of Woman magazine.

“The book was a little faded from tropical heat and rains, but I could still distinguish the very beautiful girl on its cover.”

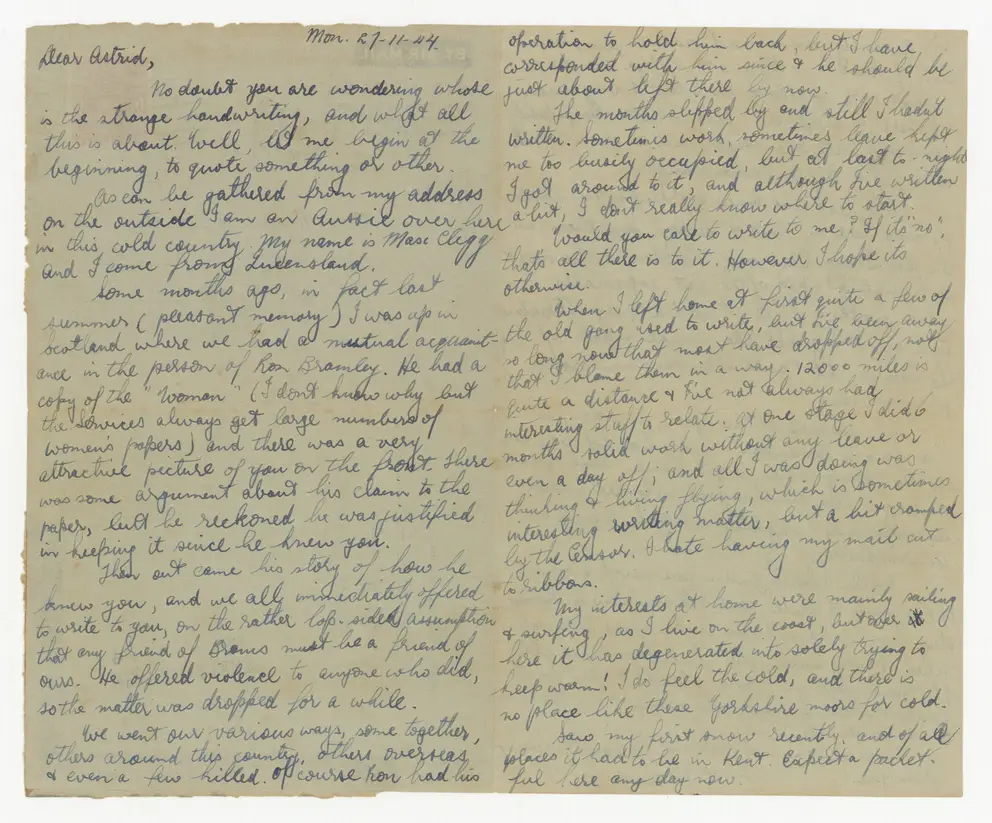

Handwritten letter to Astrid from Flying Officer Max Clegg. He writes about of his love of sailing, surfing and travelling around the United Kingdom. AWM2025.6.56

The voice of Max Clegg

Among the most touching letters are those from Flying Officer Bernard ‘Max’ Clegg, a wireless operator with 460 Squadron, RAAF. He was a member of Bomber Command, based at RAF Binbrook in Lincolnshire, England.

On the page his voice is warm, charming and familiar.

“Dear Astrid, no doubt you are wondering whose is this strange handwriting

“Let me begin at the beginning.”

Max explains he first saw Astrid’s photo in Scotland, through a mutual acquaintance named Ron Bramley.

“He had a copy of the Woman… then out came his story of how he knew you, and we all immediately offered to write to you, on the rather lop-sided assumption that any friend of Bram’s must be a friend of ours.

"He offered violence to anyone who did, so the matter was dropped for a while.”

Clegg and his crew of 460 Squadron RAAF, England, January 1945. Clegg is standing, far left.

Flying Officer Bernard Maxwell Clegg, (wireless operator) [detail of P04171.005]

The Avro Lancaster bomber used by Clegg and his crew of 460 Squadron. The aircraft was shot down by German night fighters on 21 February 1945.

His letters must have struck a chord with Astrid, as he sent a second letter roughly six weeks later.

“Very pleased to get your letter, as I haven’t had any Aussie mail for just about three weeks. Was beginning to wonder if the place was still there.”

“Your mention of surfing tempts me to say ‘what’s that?’, as it is so long now since I had a surf that I have almost forgotten what it is. And as for my once beaut suntan – it has totally vanished, though I will say that I am not as white as some of these English chaps.”

Max mentions the bombings in London and his concern for friends, including Ron Bramley.

“I haven't seen Ron for months now and don’t know what has become of him.

“Just lately when I haven’t heard from several friends for a while, I’ve learnt that they have ‘gone in’ or are ‘Missing’.”

It would be his last letter.

In the early hours of 21 February 1945, Max and his crew were returning from a bombing raid on Dortmund, Germany, when they were attacked by a night fighter. According to the pilot – Australian Flight Lieutenant Alex Jenkins – the plane was hit without warning. Jenkins was the only survivor.

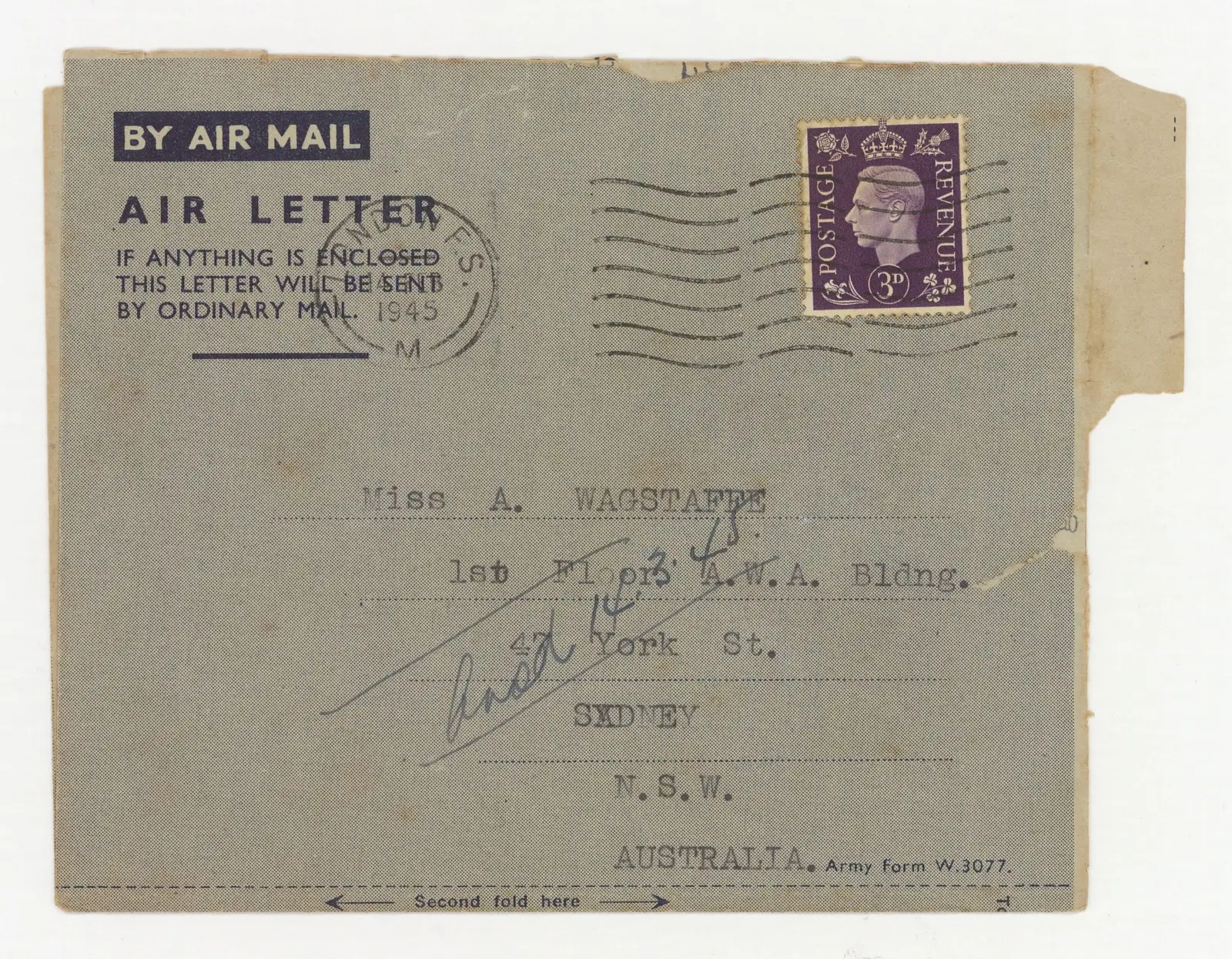

Max had been killed just a week after his final letter to Astrid. The postage stamp dated 14 February 1945 – Valentine’s Day.

Envelope addressed to Astrid from Flying Officer Bernard 'Max' Clegg. AWM2025.6.56

Remembering Astrid

Astrid herself would be killed in an accident a year later.

On 6 April 1946, Astrid and her sister Patricia, 24, went out with two Navy servicemen. Their car struck a stationary lorry, rolling four times, throwing the passengers from the vehicle. Astrid, in the back seat, was killed. She was just 21 years old.

The driver of the car, Lieutenant Lyle Carr, was initially charged with manslaughter. In the end, the court ruled the tragedy an accident and Carr were found not guilty.

Astrid Wagstaff. Courtesy of Hilary Cleland.

The Sun Newspaper, 7 April 1946. Courtesy of Trove.

Her niece Hilary said the crash had a profound effect on the family.

“Patricia was very effected by the whole ordeal, and their mother mourned the loss for the rest of her life.”

Hilary’s mother, Dahlas, was living in England at the time and was not able to return for the funeral. She named her daughter Hilary Astrid, in honour of her sister.

“Astrid is buried with her parents and sisters. Each Anzac Day, I visit their graves to lay flowers.”

The letters form a time capsule – a glimpse into a generation of young people caught up in extraordinary circumstances.

By donating the collection of letters, Hilary Cleland hoped Astrid would be remembered not only for her beauty and kindness, but also for the way she connected with others. She wanted people to know how much she meant to the young men who saw something special in her and took the time to write.