In August 1944, 168 Allied airmen, including nine Australians, were falsely accused of being terrorists. They were not sent to a prisoner of war camp, as set out in international law, but to Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany.

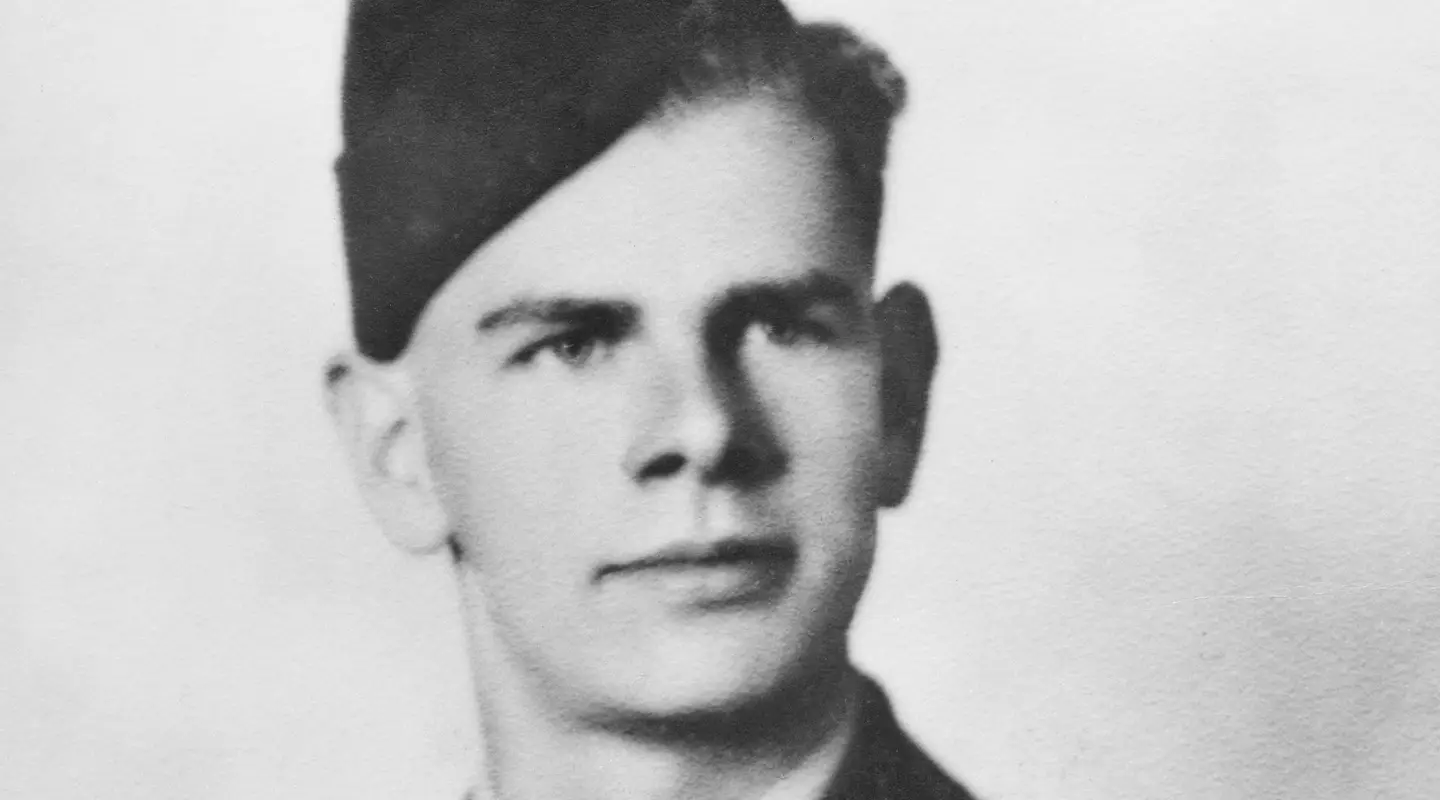

Portrait of Flight Sergeant Keith Mills

On a clear summer night, with the target well behind them the crew of Halifax MZ692 ‘P for Peter’ heard two loud bangs and saw their aircraft wings catch fire. After hearing the order to bail out, navigator Keith Mills fixed his parachute, kicked out the escape hatch and fell into a starry sky.

In August 1944, 168 downed Allied airmen were deported from a Paris prison to Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany. The men were from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Jamaica.

Falsely accused of being terrorists and saboteurs, these airmen were not sent to a Stalag Luft (prisoner-of-war camp for airmen) as set out in international law; instead they were transferred to Buchenwald, notorious for its crematoriums and its program of medical experimentation on prisoners.

The men, nine of them Australians, spent a number of months at Buchenwald before being transferred to Stalag Luft camps, where they remained until war’s end.

The story of the Australian airmen held at Buchenwald is little known.

Buchenwald concentration camp was a huge forced-labour prison, holding mainly Russians but also common criminals, Jews, Poles, Gypsies and homosexual prisoners. Everyone held at Buchenwald witnessed the horror and brutality of Nazi tyranny.

Doing time

While the Allied flyers were at Buchenwald they had no contact with the Red Cross, no parcels, little to eat, less to do. The key difference between the airmen and other inmates was that they were not allowed to work. They simply languished. They would not have known it at the time, but the airmen’s identity cards at Buchenwald were marked ‘Dikal’, a shortening of ‘Darf in kein anderes Lager’- meaning ‘not to be sent to another camp’. Their prospects of survival were very slim.

To give them a sense of purpose and order, formal meetings began under the leadership of ranking officer Royal New Zealand Air Force pilot Phil Lamason, and in October 1944 the Konzentrationslager Buchenwald, or KLB Club came into being.

The singular purpose of the club was to boost morale and maintain comradeship. The airmen – while maintaining military rank and protocol – exchanged ideas, gave talks, and made a pact to survive and to bear witness. They designed a logo for the Club: a naked, winged foot with ball and chain attached (symbolising the barefoot condition of the airman while in camp), mounted on a white star, the symbol of the Allied invasion forces.

When the war was over, members of the KLB Club commissioned a large pin or brooch with this logo, and all those still alive were allocated one.

Two of the airmen died (one from the Royal Air Force, the other from the United States Army Air Forces) at Buchenwald concentration camp, both from illness and neglect.

Portrait of Squadron Leader Phil Lamason DFC and Bar. It was thanks to the efforts of Lamason that the airmen were transferred out of Buchenwald and into Stalag Luft camps. Photographer unknown.

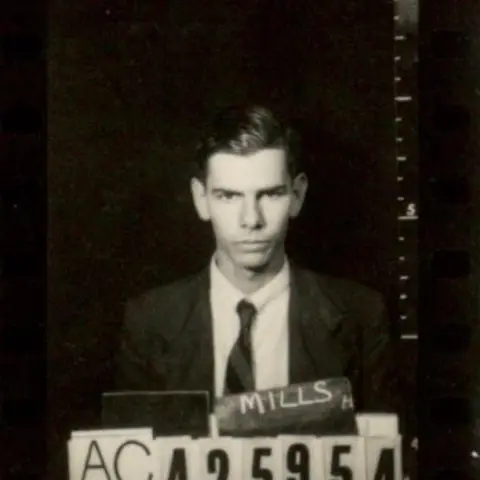

Flight Sergeant Keith Mills. Coutesy of National Archives of Australia.

A flying start

Keith Mills was born on 2 January 1924, the son of a general store-keeper. After a carefree childhood in Mackay, Queensland, Mills travelled to Brisbane to enlist in the Royal Australian Air Force, aged 18. After a brief introductory ground school to study aeronautics and the theory of flight, Mills learnt to fly at No. 8 Elementary Flying Training School at Narrandera, NSW.

Though he completed the pilot’s course, Mills was re-mustered as a navigator and sent on to Bradfield Park, Sydney, for further study of navigation and mathematics. Three months later Mills embarked for Canada to train at No. 2 Air Observers School in Edmonton, Alberta, where he was awarded his navigator’s badge.

Having completed this final advanced stage of the Empire Air Training Scheme, Mills sailed for England, where he crewed up and was posted to No. 78 Squadron at RAF Breighton in June 1944.

It was here that many RAAF men, including Keith Mills, took part in a cricket match against an English team.

Arriving at the ground, the Australians were given a royal reception by the huge crowd that had gathered. It transpired that an over-zealous cricketing scribe had mistaken the name Keith Mills on the team sheet for that of another RAAF serviceman – Keith Miller, perhaps the greatest all-rounder Australia had ever produced. Now a Flight Sergeant, Mills was part of a seven-man crew, all bar one of whom were Australian. From enlistment to operational readiness had taken them just over two years.

On their very first operational flight, on the night of 22 June 1944, in Halifax ‘P for Peter’, Mills’ crew were detailed to bomb the railway yards at Laon in northern France.

Having successfully bombed the target and now homeward bound, their aircraft was attacked by a Ju-88 and caught fire.

Pilot Bob Mills (no relation to Keith) gave the order to bail out, and the crew managed to leave the Halifax and parachute out successfully. From the ground, Keith Mills saw his aircraft explode, the fireball lighting up the night sky.

Evasion

All aircrew had received some instruction in evasion techniques. They knew that once on the ground, their best chance of survival was to separate, hide by day and try to make contact with the Resistance.

‘P for Peter’s’ British Flight Engineer Charles Wright, was captured almost straight away and sent to Stalag Luft VII for the rest of the war.

Separately, two other crew members, Mid-Upper Gunner Douglas Foden and Air Bomber Ian Innes, managed to evade successfully, returning to England in less than three months.

Two of Keith Mills crew who were with him at Fresnes and Buchenwald. Left, Wireless Operator Flight Sergeant Eric Johnston and right, Flight Sergeant Jim Gwilliam Rear Gunner.

Photographer unknown.

After five days on the run, sheltering in bushes and haystacks, Keith Mills made contact with the Resistance. He was passed from house to house until a more stable arrangement could be found for him. Nearly a fortnight after being shot down and thanks to the Resistance network, Keith Mills was reunited with his Wireless Operator Eric Johnston, Pilot Bob Mills, and Rear Gunner Jimmy Gwilliam. They spent nearly five weeks being sheltered by French civilians in the village of Coivrel. The men were well cared for and given civilian clothes.

Told they were going to be flown back to England, the men were instead betrayed by a collaborator and taken to Beauvais gaol. They were interrogated and savagely beaten – particularly Keith Mills and Bob Mills, as the Gestapo thought they were brothers and tried to thrash information out of them. Dressed as they were in civilian clothes, the men were repeatedly accused of being saboteurs and spies. Had they been in their military uniforms, the Gestapo would have sent the men to one of the many Stalag Luft camps for Allied airmen.

After three days the men were transferred to Fresnes, an infamous prison used by the Nazis to torture and hold French resistance fighters and Allied secret agents.

Meanwhile, after breaking through at Normandy and fighting their way to liberate Paris, the Allied forces were approaching Fresnes, so the prison was emptied. Two thousand prisoners from Fresnes – most of them French, but including the airmen – were herded into railway cattle boxcars (as many as 75 men in cars) and spent five days travelling to Buchenwald. The weather was hot, the cars poorly ventilated, and there was not enough room for everyone to sit. Many of the prisoners were suffering from dysentery. Several times during the journey the train was strafed by Allied aircraft. At one point a French prisoner, just a boy, was shot dead for simply looking out a window grille.

On the railway journey from Fresnes to Buchenwald, as the train passed through Frankfurt, a Red Cross Official was spotted on the platform. At great personal risk, Royal New Zealand Air Force prisoner Phil Lamason managed to throw him a note which briefly stated that many of the men in the cattle boxcars were Allied airmen and not civilian prisoners. Keith Mills credited that action as the initial catalyst in Lamason’s subsequent dealings with the Luftwaffe (German Air Force).

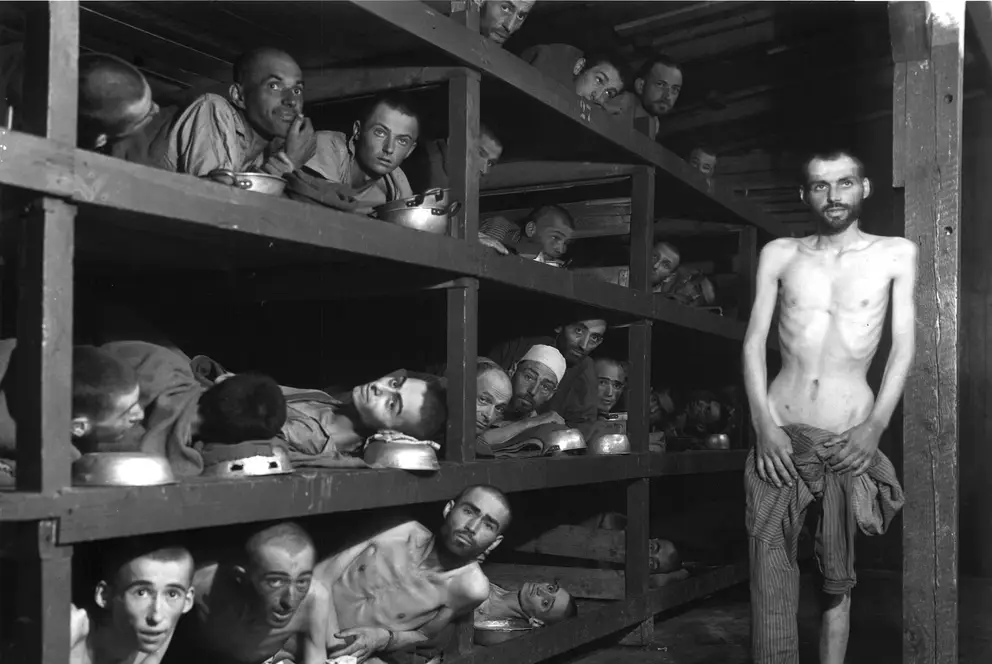

Liberated inmates of Buchenwald Concentration Camp, April 16, 1945. Photographer: Harry Miller, U.S. Signal Corps. ©National Archives, Washington

At Buchenwald

On arrival at Buchenwald all prisoners were stripped, shaved and issued blue and white striped uniforms with hats, but no shoes. For the next eight days they slept on open ground without blankets. They were later moved into a rough wooden hut with an earth floor, no windows, and four tiered shelves for sleeping. The huts were extremely overcrowded, with five or six men sharing a space four feet wide on the wooden shelves. Many prisoners were suffering from tuberculosis and dysentery.

Soon after arriving at Buchenwald, the airmen witnessed a large stream of American Flying Fortress aircraft bomb the armaments factory outside the camp where prisoners were forced to work. Although the objective was clearly to destroy the factory, nearly 400 prisoners were killed.

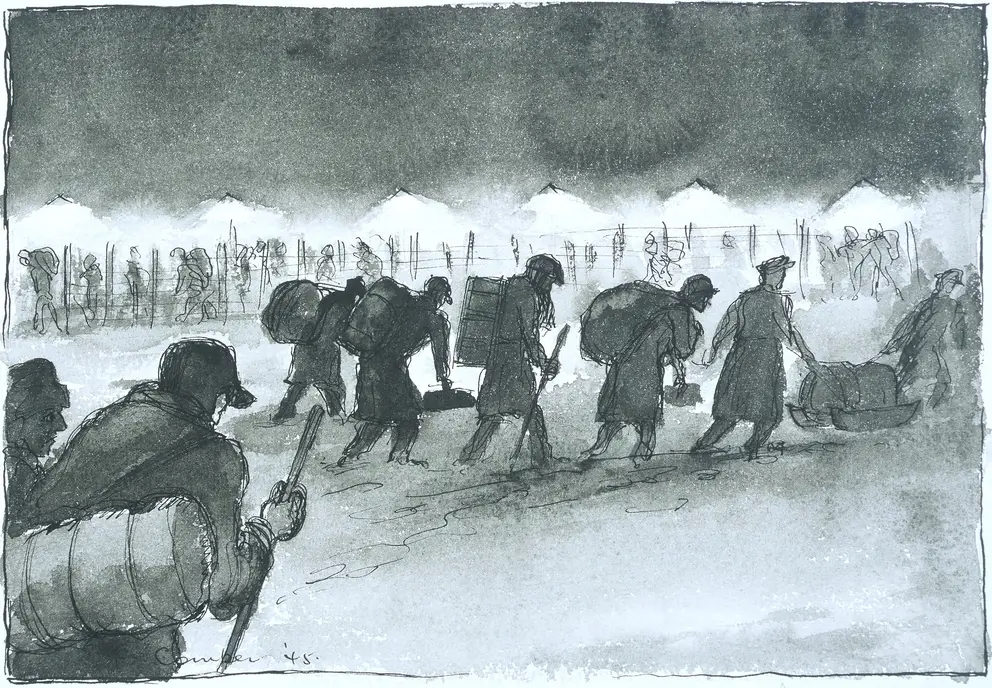

The artwork, The shapeless ghosts leave camp: Stalag Luft III, 1945 by Albert Comber shows prisoners of war on the long winter march from one POW camp to another.

After the war, in a RAAF intelligence de-briefing, Keith Mills was asked to record any atrocities he had witnessed while he was a prisoner of war. At Buchenwald Mills saw a Polish prisoner hanged for attempting to escape. He witnessed Gypsy children, inmates of Buchenwald, taken away to be gassed in vans. He observed killings, torture, beatings, the exposure of prisoners-of-war to danger, and a total failure to provide prisoners with proper medical care, food or quarters.

Keith’s pilot Bob Mills was detailed to pull a handcart around the camp in the morning to collect the bodies of those who had died in the night. Bob then had to push the cart into the crematorium, where he witnessed emaciated corpses being fed into ovens.

The men spent 60 days at Buchenwald before, thanks to Royal New Zealand Air Force prisoner Phil Lamason, Luftwaffe officials were pressured into removing the airmen from the camp. They were then marched to a train and transported to Stalag Luft III. Here their experience as prisoners of war became more standard. Still facing the depression of being held in captivity, still hungry and overcrowded, for the men at least conditions at Sagan were described by Mills as ‘fair’.

The worst came in freezing January as the Soviet Army advanced on the Eastern front and German authorities evacuated prisoner-of-war camps to delay the liberation of prisoners.

With Soviet troops only 20 kilometres from the barbed wire fence, the guards at Stalag Luft III were determined to keep their prisoners out of Allied hands. Close to midnight on 27 January 1945, prisoners were marched out of camp into the freezing dark and heavy snow. With the crewmates he had been with since their betrayal in France six months earlier, Mills and the men of ‘P for Peter’ were forced to march for more than a week towards Berlin in bitter conditions with little food or shelter.

They reached Luckenwalde prisoner-of-war camp and remained there until it was liberated by Russian soldiers on 22 April 1945.

Prisoners of war (POW) from Stalag VIII B (344), Lamsdorf, Silesia (now Lambowice in Poland) during an enforced march westward to escape the advance of Soviet forces.

Prisoners of war from Stalag VIII B (344), Lamsdorf, Silesia (now Lambowice in Poland) during an enforced march westward to escape the advance of Soviet forces.

Release

For the first 282 days of his imprisonment, Keith Mills had received no mail and no clothing parcel. It was three months after he was shot down before he was able to write a Red Cross letter home to let his family know he was still alive. But Mills survived, as did the rest of his crew, and they were flown out as part of Operation Exodus, the airborne repatriation of 354,000 British prisoners-of-war, and reached England close to a year after they had left.

Keith Mills returned to Mackay, where he married Valerie Garner in 1947; the following year they opened a general store which they ran for almost forty years. They raised five children.

Under an agreement signed with West Germany in 1964, money became available to British victims of Nazi persecution. The British KLB Club airmen from Buchenwald received a basic compensation, but when Australian servicemen lodged their claims, they were knocked back. The Australian government denied that any of their servicemen had ever been held in concentration camps. This injustice was made worse by the men’s Stalag Luft prisoner-of-war records, which did not indicate that they had come from a concentration camp. Only persistent lobbying for more than twenty years – from the airmen, a journalist, and a single government minister, Minister for Foreign Affairs Bill Hayden – finally brought results. The claimants, 27 Australians – most former soldiers held at Auschwitz and Dachau – received an ex gratia payment. It was a huge relief after years of denial and rebuttal, and on 24 June 1988, the members of Keith Mills’ crew met in Canberra and celebrated their compensation payment.

Surviving Buchenwald airmen held a reunion in 1988 to meet again and celebrate their compensation. Left to right: Tom Malcolm, Kevin Light, Eric Johnston, Jim Gwilliam, Keith Mills, Bob Mills. Photographer unknown.

At the Memorial

With the development of the new Anzac Hall and the Australians in Bomber Command exhibition, the Memorial’s curatorial team wished to include the story of the small group of Australian airmen held at Buchenwald: their experience is as extraordinary as it is compelling, and the story had never been told in the Memorial’s galleries. Not only did these men serve their country, bail out of a burning aircraft, parachute to safety and evade capture: they endured the largest and arguably most brutal concentration camp in Germany, in the process witnessing the Holocaust first-hand.

Caterpillar Club pins were awarded to airmen whose lives were saved by parachutes.

Thanks to the era of the internet, curators managed to find the family of Keith Mills. His children could not have been more helpful.

They shared information and documents, and made donations: his uniform, medal group, Caterpillar Club pin (awarded to airmen whose lives were saved by parachutes), prisoner-of-war identity disc, and his Konzentrationslager Buchenwald KLB Club badge.

Keith Mills was the last surviving Australian airman to have been imprisoned at Buchenwald.

He was an active father; he loved fishing and family and friends. He was modest and generous, and although his children knew he had served in the RAAF, had been shot down and taken prisoner of war he never revealed details of his ordeal. It was not until an article on his experiences was published in mid-1988, after recognition had finally come for Australians held in Nazi concentration camps, that Keith’s family knew what he had been through.

A report by a British parliamentary delegation who visited Buchenwald on 21 April 1945 describes its policy of steady starvation and inhuman brutality. Though it is a restrained and objective report it describes camps like Buchenwald as marking ‘the lowest point of degradation to which humanity has yet descended’.

It is incredible that Keith Mills, like so many former prisoners of war was not bitter, nor saw himself as a victim. or

Australians in Bomber Command 1939-1945 gallery

When it opens, the Australians in Bomber Command 1939-1945 gallery will exhibit many objects new to the Memorial’s collection - objects that have never been publicly displayed - and examine new aspects of this epic campaign. Historians and curators are very grateful to the family of Keith Mills and very pleased to be able to tell his story.