An outdated weapon still played an important psychological role.

Bayonets have been used in battle since the seventeenth century, having evolved from the pike as an ancillary weapon for the single-shot musket. The bayonet enjoyed two hundred years of use in battle.

Fighting during the American civil war and Anglo-Prussian was demonstrated how ineffective the weapon was in the face of superior firepower, as men with single-shot rifles and bayonets faced rapid-fire weapons and accurate artillery for the first time. For troops who fought the First World War, however, the bayonet was a weapon that gave men the confidence to encounter their enemy on the battlefield. So routine and effective was their training with the weapon that Australian troops emerged from the First World War with the reputation for being able to employ the bayonet with ferocity and skill in close-quarter fighting.

The Pattern 1907 sword bayonet was made for use with the .303 Lee Enfield rifle and was part of the Australian soldier's kit in both the First and Second World Wars

On the eve of the First World War the bayonet was on the forefront of a tactical dilemma. Traditional methods of warfare were challenged by new weapons such as the machine-gun and artillery, which threatened to replace the tactics of rapid mobility with stalemate. These weapons were designed to overwhelm the enemy with firepower from greater distances, but exponents of traditional methods were sceptical of the modern doctrine, maintaining the wars were won by “the spirit of the offensive”. Artillery and machine-guns could suppress the enemy’s fire, demoralise him and destroy his defences, but no more: it was still the role of the infantry and cavalry, the traditionalists said, to gain the ground from hm at the point of the bayonet and sabre.

Just how challenging modern warfare was to traditional methods became clear during the initial campaigns of the First World War – or for the Australians, just a few months after arriving on Gallipoli. On the morning of the 7 August 1915, two regiments of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade mounted an assault at the Nek as part of major push on the Sari Bair ridge, while the New Zealander’s attacked Chunuk Bair. A combination of field guns, howitzers and naval gins fired in support of the dismounted light horseman to suppress fire from the Turkish positions; but the allied bombardment stopped before the ground assault was launched, which gave the defenders enough time to man their defences. When the light horsemen rushed from their positions seven minutes later, armed with bayonet and rifle, they were cut down by a wall of machinegun and rifle fire and fell just a few metres from their parapet. A second and third wave followed with similar results, and within fifteen minutes, 234 Australians lay killed and 140 wounded.

No one actually believed that a charge head-on into unsuppressed machine-gun fire was tactically viable, but the failure of the ground assault to coincide with the artillery bombardment emphasized the importance of command and control during combined arms operations. It would be the latter half of 1917 before the doctrine of close tactical co-ordination between arms was mastered, a lag that cost the Australians dearly at Fromelles, Pozières, Bullecourt, and in numerous trench raids throughout the war.

Despite the failure at the Nek, however, bayonet assaults were employed on the Western front. Lieutenant Charles Pope, 11th Battalion, was commanding an advance piquet at Louverval on 15 April 1917 that became cut off and surrounded when 23 German battalions attacked the Lagnicourt area. His men having expended all ammunition defending the position, Pope led them in bayonet charge head-on into the German infantry. Some reports claim that the charge accounted for eighty Germans before the entire piquet of twenty men were themselves overpowered and killed.

Pope’s attack stopped the German advance in his sector, and for maintaining his post at all costs, he was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. The bayonet failed to stem the greater German counter-attack at Lagnicourt, and did little to save Pope and his men from being killed. Nonetheless, the light horsemen at the Nek and Lieutenant Pope’s piquet had left their positions and charged head-on into the enemy. They were motivated by confidence in their ability to fight at close quarters, which had developed over months, even years, of training in hand-to-hand combat.

Men of the 28th Battalion carry out bayonet training near Hazebrouck, France, in September 1917

Bayonet drill played an important role in mentally preparing soldiers for battle; it used aggression to imbue the wielder of the bayonet with confidence to overpower his opponent and kill him before he had a chance to do likewise. According to the Manual on the training of platoons for offensive actions. Issued to officers in 1917, confidence in combat was gained through “being blood-thirsty, and forever thinking how to kill the enemy”, and through platoon commanders using bayonet training to foster bloodlust for the enemy. By 1916, Australian troops were being instructed to temporarily incapacitate the enemy and then use the bayonet against vulnerable parts of the body such as the “face, throat, chest and thighs when enemy is facing and the region of the kidneys when the back is turned”. One training officer lecturing Australian NCO’s in France in July 1916 wrote:

It is the spirit of the bayonet which urges on the assault [and] makes a man stand and meet the counter-attack with the bullet. It is the spirit of the offensive and the spirit of determination. Realise this and inculcate it into every one of your men. Instil it into them … by practice … carried out daily if possible and always with the true offensive spirit.

Inculcate the “spirit of the bayonet” they did. The Australians trained in Egypt during and after the Gallipoli campaign, by which time they were well practised in the art of bayonet fighting. During periods of inactivity, bayonet training was a routine part of life in the rear area on the Western Front as well as in the training camps of Australia and England.

Writing of the 3rd Division going into action at Messines in June 1917, the official historian Charles Bean described how the order to fix bayonets before battle “always stirred a supressed excitement” among Australian troops, who “were always keen for the experience of plunging a bayonet into an enemy". Some units cultivated distinctive techniques with the weapon in order to foster the offensive spirit. Men of the 15th Brigade were trained in what Brigadier General “Pompey” Elliot dubbed the “throat jab”: a thrust “under the chin and up into the spinal cord”, making it “most deadly and difficult to parry … Our men practice it assiduously … and in a melee it makes them invincible.”

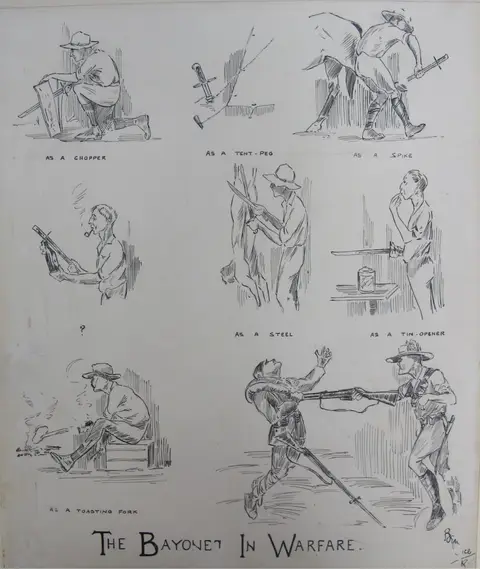

Because the static nature of trench warfare restricted the bayonet’s use to raids and major attacks, it became a weapon that fulfilled a multitude of more practical roles, from chopping wood to opening tins. Just 0.28 per cent of Australian battle casualty admissions to the field ambulances on the Western Front were bayonet wounds. This shows how rarely the weapons were put to their intended use in trench warfare.

The bodies of a German machine-gun crew killed during the 13th and 15th Brigade's attack on Villers-Bretonneux on the night of 24-25 April 1918. Greatcoats cover wounds to horrific to photograph.

When a face-to-face encounter with the enemy did come bout, however, Australian troops were ruthless. On the night of 24-25 April 1918, the 13th and 15th Brigades launched a counter-attack to recapture the village of Villers-Bretonneux, which had fallen under German occupation the morning before.

Under the cover of darkness, and without artillery support to warn of the impending attack, the Australians crept up to the German machine-gun positions dug into the hillside on the fringes of the village.

The official history relates how, with the tactical advantage of surprise and a “ferocious roar and the cry of ‘Into the bastards boys’”, the Australians descended on the German positions with their bayonets, employing the deadly throat jab.

Sergeant William Downing , 57th Battalion, recalled “ a howling as of demons” when his battalion went into action that night, describing how “bayonets passed with ease through grey-clad bodies and were withdrawn with a sucking noise” as the Australians overran and killed German machine-gun crews, some of whom threw away their weapons as they attempted to flee. Intoxicated with bloodlust, the Australians showed little mercy and took few prisoners.

“Each man was in his glee and old scores were wiped out two or three times,” recalled one participant in the melee, while the 15th Brigade intelligence officer reported the men “had not had such a feast with their bayonets before”. The counter-attack was so effective that the Australians were able to continue their drive and push on into Villers-Bretonneux, retaking the village on the third anniversary of the landing at Gallipoli.

William Longstaff, Night attack by 13th Brigade at Villers-Bretonneux, The "throat jab" is depicted on the far left of the painting.

The official historian dealt with this unpleasant aspect of the Australian experience with a sense of unease, and drew the conclusion that the callous behaviour of men in close-quarters fighting was “inseparable from the exercise of the primitive instincts”. Perhaps he was right.

When their blood had had a chance to cool, however, men struggled to comprehend the gruesome act of face-to-face killing with the bayonet. After the attack at Villers-Bretonneux, Lieutenant John Christian MC, 59th Battalion, found some under his command showing remorse for going in too hard. “I can’t help thinking of that chap I bayoneted,” they confessed in the days after the attack.

Although it motivated the man who used it, the thought of being bayoneted was so horrible that it had a tremendous demoralising effect on the enemy. Having withstood heavy artillery bombardment, for many German defenders the sight of Australin infantry advancing towards the with bayonets fixed was enough to persuade them to a hasty surrender. Charles Carington, a British officer with the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, recalled: “I never knew the enemy to stand if your men with their long gleaming blades could get to charging distance.”

A cartoon from Kia-Ora from August 1918 making ironic comments on the bayonet's many practical uses.

In its coverage of the battles of Third Ypres in 1917 and the Allied offensive in 1918, the Australia official history gives numerous examples of shattered German troops emerging from pillboxes and heavily defended positions with their hands and souvenirs in the air, pleading for mercy, as Australian troops approached with rifle and bayonet.

Tenacious machine-gunners who made their intensions to surrender know too late, on the other hand, were shown little mercy, which acted as an incentive for other defenders not to hold on so stubbornly. Even at times when they were superior in numbers, groups of unarmed German prisoners of war were deterred from trying to overpower their escort and make their escape by the prospect of being run through with the bayonet – an ever-present weapon in the hands of sentries.

In the face of unsuppressed machine-gun and artillery fire, bayonet assaults such as the one at the Nek and Lieutenant Pope’s stand at Louverval may have been heroic, but were also futile and bound to fail. With adequate support from machine-guns and artillery, and the element of surprise, however, the bayonet was a fearful weapon which fulfilled the purpose of imbuing troops with the morale and confidence to overwhelm their enemy at close quarters and gain the ground from him.

When it eventuated, bayonet fighting was cold, hard and bloody, but it was the means by which Australian troops fought their enemy face-to-face during the First World War.