In the Second World War, a number of women served as agents amid the dangers of occupied Europe.

Her boots slipping on the dry larch needles that covered the rocky outcrops, Krystyna Skarbek scrambled ever higher up the goat tracks that led to the Nazi German garrison on the Col-de-Larche, a strategic frontier pass in the Alps. The fort dominated the surrounding terrain, effectively controlling the military route to the large French garrison town below. It was a hot day in early August 1944. Skarbek tied back her hair with a white and red silk scarf – her weapon of choice to take on the garrison above.

Portrait of Krystyna Skarbek OBE, GM, C de G. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery NPGx201396

Following D-Day in June, the Allies were slowly pushing the Wehrmacht back through France. The fear in the south-east region was that an unknown quantity of enemy troops … possibly Italian, possibly German, perhaps as many as seven divisions … were stationed in northern Italy, ready to attack over the Alpine passes.

The Polish-born Skarbek, serving with the British Special Operations Executive, or SOE, in partnership with the local French resistance, had learnt that the German fort on the Col-de-Larche was manned largely by conscripted Polish troops. These men had been taken from disputed territories and forced labour camps. Unsure of their loyalty, the Germans had posted the Poles away from the Polish front and regularly moved them around – but had not counted on their meeting a Polish speaker in the Alps.

When she reached London in late 1939, Skarbek had made her way to the headquarters of the British Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6. The first record of her in the files is a December 1939 memo describing her as a “flaming Polish patriot … expert skier and great adventuress”.

Not so much volunteering as demanding to be taken on, Skarbek had submitted a bold plan to ski, possibly from Slovakia, over the Carpathian mountains into enemy-occupied Poland. She would take in news, propaganda and money for the fledgling resistance, and gather military intelligence for the Allies before returning.

She spoke the right languages, had extensive contacts, and even knew the smuggling routes across the mountain border passes because, as a thrill-seeker some years earlier, she had brought in contraband cigarettes. “She is absolutely fearless,” MI6 closed their report, signing her up despite the then-problematic twin issues of her foreign nationality and female gender. As a result, Skarbek became the first woman to serve Britain as a special agent during the Second World War, more than a year before the SOE, into which she was later transferred, was established.

The first record of her in the files is a December 1939 memo describing her as a “flaming Polish patriot … expert skier and great adventures”.

Skarbek had already undertaken four perilous missions into occupied Poland, establishing early communications between the resistance and their British allies, gathering and delivering intelligence, and helping to evacuate downed pilots and escaped prisoners of war. Eventually she had been arrested at her lover’s apartment, but managed to avoid interrogation by biting her tongue sufficiently hard that she could feign coughing up blood – a symptom of tuberculosis. Rightly terrified of this disease, the Germans had quickly released her. The following day she crossed the border west, hidden in the boot of a car, bringing one last microfilm of military intelligence with her, stashed inside her gloves.

After Poland

Skarbek would eventually see service in three theatres of the war. After Poland, she worked in Egypt and the Middle East, before becoming the only female agent to parachute from North Africa into German-occupied France in the summer of 1944. It was there, while serving as a courier for an SOE resistance circuit, that she learnt about the conscripted Poles manning the Col-de-Larche garrison.

This Suitcase Wireless Set 'A' Mk 1 is one of the first wireless sets disguised via suitcase to be produced by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) during the Second World War.

Eventually reaching the concrete, stone and strengthened steel platform that composed the edge of the fort, she carried out a careful reconnaissance, knowing the nervous German commanders were vigilant for local partisans aiming to attack.

Once sure the coast was clear, she called out to a pair of Polish perimeter guards in their native language. When, instead of opening fire, the astounded men called back, Skarbek took her life in her hands and emerged from the trees holding her white and red headscarf aloft: unfolded, it was the Polish flag.

After a frantic conversation, Skarbek won the men’s trust. A week later she returned, persuading the more than sixty Poles at the garrison to defect at an agreed date. They were first to render their heavy weapons useless by removing their breech-blocks and firing pins, and to collect as many mortars and machine-guns as they could, to bring down to the French resistance.

It was through Skarbek’s ‘own personal efforts’ that she achieved ‘the complete surrender of the Larche garrison’, one of her SOE colleagues later wrote. The local resistance leader reported that her work ‘had been nothing short of remarkable’ and ‘of the greatest value to the Allied cause’.

The SOE

Krystyna Skarbek’s early successes would help to overcome official reluctance in the SOE to recruiting other women to the role. Established in July 1940 after the fall of France, the SOE was created to support resistance in occupied territory. It was organised into sections by country, and its initial aim, as Churchill put it, was ‘to set Europe ablaze’. Trainees who passed the rigorous courses in fitness, orienteering, weapons, explosives and silent killing (with just a knife, a rope or the hands) went on to learns specialisms such as breaking and entering, losing a tail, parachuting, wireless transmitting, morse and coding.

Teams of three (a network leader, a courier, and a radio operator) would then be delivered behind enemy lines to create and run resistance circuits. They brought with them not only a morale boost but also weapons and ammunition, training opportunities and, vitally, a communication link with London. Establishing radio contact meant resistance groups could not only organise the supply of arms but also run operations as part of a coordinated national strategy, rather than simply responding to localised hostilities.

There was a problem, however. Able-bodied men of conscription age moving around occupied territory inevitably attracted attention. Compounding this, in June 1942 Germany imposed the Service du travail obligatoire on France, enforcing the enlistment and deportation of hundreds of thousands of French workers to serve as labourers for the German war effort.

As a result, thousands more young men fled to the hills, where they established resistance camps, calling themselves the ‘Maquis’ after the scrubby terrain. A generation of Frenchmen were either in hiding, prisoners, deported or dead, but women of all ages were still travelling around to care for family and keep businesses running. For once, women could exploit their gender superpower: not seduction, but their ability to be largely overlooked and underestimated.

Lieutenant Odette Sansom GC, MBE, served with great distinction in France and after being captured, survived repeated, brutal interrogations, but remained unbroken. c. 1946. Imperial War Museum, HU 3213. Image courtesy of Wikicommons.

Virginia Hall DCS, C de G, MBE, worked for the British Special Operations Executive and American Office of Strategic Services. The Gestapo called her “the most dangerous of Allied spies”. c. September 1945. Image courtesy of Wikicommons.

Women at war

Nevertheless, as one SOE agent noted, in London there was still ‘definitely a hostile resistance to women being put in a combat situation’. Gendered belief about conflict was so profound that, despite a long history of active female military engagement, Britain had still chosen to exclude women from frontline service at the start of the war. Disempowered under the guise of male protection and chivalry, they were told they did not qualify for active service, did not have the required strength; they would be a liability, distract the men and weaken their resolve. Yet in 1942, the demands of war prevailed.

Although SOE’s recruiting officer, Selwyn Jepson, distinguished what he called women’s ‘cool and lonely courage’ from male bravery, women were in fact recruited from similar routes and for the same skills and qualities as their male counterparts. Anyone in the armed services with language skills was considered, and trained wireless operators were particularly sought after. Like many of the men, some women were also recruited through word of mouth or serendipity, such as when Odette Sansom responded to an Admiralty request in the press for photographs of the French coastline, but accidentally sent hers to the War Office.

Among recruits, SOE was a great leveller. The women had to pass the same fitness and endurance courses, their bodies exhausted in the same muddy fields, their minds tested through identical mock interrogations. And the women, too, were trained in weapons, sabotage, silent killing and various specialisms. Male and female experience never entirely overlapped, however, as the men were legally soldiers while the women were seconded civilians. Only their enrolment into the ‘First Aid Nursing Yeomanry’, the one uniformed women’s service to operate outside the British Armed Forces, meant they were entitled to bear arms and, if caught, might have protection under the Geneva Convention.

Known by the Gestapo as the White Mouse, Nancy Wake was highly decorated for her work with the French Resistance.

In August 1942, Yvonne Rudellat became the first trained female agent SOE sent to France, in her case by boat, where she served as a courier for the ‘Prosper’ resistance circuit for almost a year. Severely wounded during a dramatic car chase, she was captured and ultimately died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp a few days after its liberation.

Serving as a courier like Rudellat, or as a wireless operator, were the only roles open to the women, but once in the field many stepped up when their male colleagues were arrested or killed. Among these was Pearl Witherington. Parachuted into central France to serve as a courier, Witherington posed as a cosmetics saleswoman to smuggle messages, radio sets, weapons and other equipment to the resistance. When her circuit leader was arrested in June 1944, she became the only female agent to lead her own circuit. The associated group of around 2,000 Maquis proved particularly effective in sabotaging railway lines and telegraph poles to slow down German reinforcements to Normandy after D-Day.

Other women had already served in the resistance before being recruited by SOE. Born in New Zealand but raised in Australia, Nancy Wake was living with her French husband in Marseilles at the start of the war. There she became a courier for an escape-line evacuating downed pilots into neutral Spain, before being forced to follow in their footsteps when her husband was arrested, and her own identity discovered. In May 1944, SOE parachuted her back to the Auvergne region with a list of targets to be destroyed before D-Day. During one raid, Wake killed a German sentry with her bare hands to prevent the alarm from being raised.

‘aka Zo’

As well as the 39 women sent to France, others served gathering intelligence in Belgium, Egypt and Madagascar, or supporting partisans and taking part in operations in Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia and Yugoslavia. Among them was one of the very first women to undertake active service in the war.

Elżbieta Zawacka, also known as Zo, was already a member of the Polish women’s military auxiliary when she was woken by a series of explosions in the early hours of 1 September 1939.

Elżbieta Zawacka, known as Zo, was a Polish freedom fighter who carried intelligence to the Polish government in exile in London, fought in the Warsaw Uprising, and defied the Germans and the Soviets. Image courtesy Fundacja Elżbieta Zawacka

Deployed to the then Polish city of Lwów (now Lviv in Ukraine) she supplied shells and ammunition to anti-aircraft batteries, and made petrol-bombs to throw at the German and Soviet tanks invading from the west and east respectively.

After Poland was occupied, Zo joined the resistance Home Army, both gathering and delivering intelligence before being appointed as the Home Army’s only female emissary in 1943.

Having crossed almost a thousand miles of enemy-occupied territory, Zo delivered two important microfilms to London, and joined the Polish elite Special Forces being trained with SOE. She parachuted back three months later, as the only woman in SOE’s Polish section. There she played a key role in the largest organised act of defiance against Nazi German occupation – the Warsaw Uprising.

In total, around seventy-five women from thirteen different nations served with Britain’s SOE. All were courageous, had an intimate knowledge of the country in which they would serve, and were deeply committed to the Allied cause, but they had little else in common.

Most were Anglo-French, but there were also American, Australian, Belgian, Chilean, Dutch, German, Indian, Irish, New Zealand, Polish, Russian and Swiss nationals. They practised all faiths and none.

One, Noor Inayat Khan, was a Moscow-born Indian Sufi Muslim princess, and Skarbek was a countess with Jewish heritage. Others were working women, like Violette Szabo, a shop assistant from Stockwell, South London. They were of all ages; several were married, some were mothers and at least one was a grandmother. One, the American Virginia Hall, had a prosthetic leg. Many were beautiful, although this could be a disadvantage if it made their face more memorable. Despite popular perception, it was not only possible but preferable for female agents to be plain.

They were of all ages; several were married, some were mothers and at least one was a grandmother... Many were beautiful, although this could be a disadvantage if it made their face more memorable.

Survival

The women were told that their chances of survival were fifty-fifty, with wireless operators warned they had just a six-week life expectancy because German detection vans could track their radio signal down to a specific property. Thirteen of the 39 women sent to France did not return, and among female agents in all regions, a total of 16 died. A few were arrested on arrival, reeled in by the Germans using captured wireless sets and codes forced from prisoners during interrogation. Others were caught after local betrayals, or during gun fights, or exhausted over their wireless sets, or after long investigations. In all, however, 75% of the female agents would survive.

Krystyna Skarbek was Britain’s longest serving agent of the war, male or female. Unable to return to her Polish homeland under its Soviet-imposed post-war communist regime, she adopted the name Christine Granville, which she had used as one of her wartime noms de guerre, and took British citizenship in 1946. The French honoured her with the Croix-de-Guerre, and for her service to the British crown she received the George Medal and OBE.

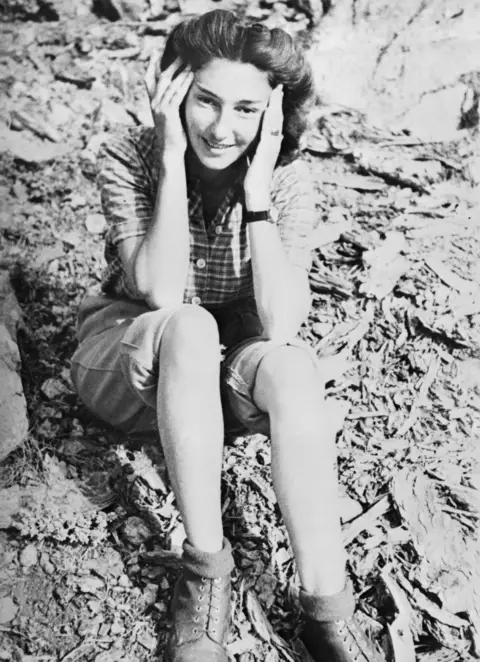

Violette Szabo recovering from an injury sustained during parachute training, 1944. NAM. 1994-07-296-44. Courtesy of National Army Museum.

Three of the women, Noor Inayat Khan and Violette Szabo, both executed, and Odette Sansom, who had not spoken under the most brutal interrogation, were awarded the George Cross, Britain’s highest award for non-operational gallantry or gallantry not in the presence of an enemy.

These were all civilian honours because, as women, the female agents were not entitled to British military honours. “There was nothing remotely ‘civil’ about my service,” Pearl Witherington commented. One of the great ironies of this history is that it was lack of recognition that had helped to make many female agents so effective during the war; but even as their service was being recognised afterwards, this misogynistic oversight continued.

Today, Britain’s female agents are honoured anonymously, among more than seven million other women with London’s Monument to the Women of World War II. This is a bronze memorial, box-shaped, hollow and nearly seven metres tall. On it are hung, as if on clothes hooks, a range of women’s empty uniforms and other outfits, far above the head of the viewer.

No actual woman is represented. However, there is also a white marble memorial on the village green at Tempsford, in Bedfordshire, near the Special Duties Squadron airfield from which so many of the women were flown out to enemy-occupied territory. Onto this stone pillar are etched the names of nearly all the women who served behind enemy lines as agents with the SOE.

The greatest memorial to these women, however, is the defeat of Nazi Germany. After the war, Eisenhower wrote that, supported by the SOE, the resistance “throughout the whole of occupied Europe, played a very considerable role in our total and complete victory.” It is impossible to distinguish the value of the women’s contribution to the Allied war effort from the men’s, because they served in mixed teams, and often in the same roles, and this is how they should most fittingly be remembered.