Thousands of Australian and British prisoners of war, worked under brutal conditions to finish the infamous Burma–Thailand Railway. A staggering 44 per cent of the men would not survive the ordeal.

For most men of F Force, the months from May to October in 1943 were the worst of their entire wartime experience. Spread across several Japanese prison camps near the Burmese border in Thailand, the group, originally made up of 7,000 British and Australian prisoners from Singapore, worked under brutal conditions to finish the infamous Burma–Thailand Railway. An early monsoon had settled in, and without adequate food or medical supplies, a cholera epidemic was taking a heavy toll on the men. Australian Lieutenant Andrew Hyslop recorded in his secret diary on 18 August that the men were “straining exertion to get order out of chaos” amid the “piping treble of the dying”. A staggering 44 per cent of the men would not survive the ordeal.

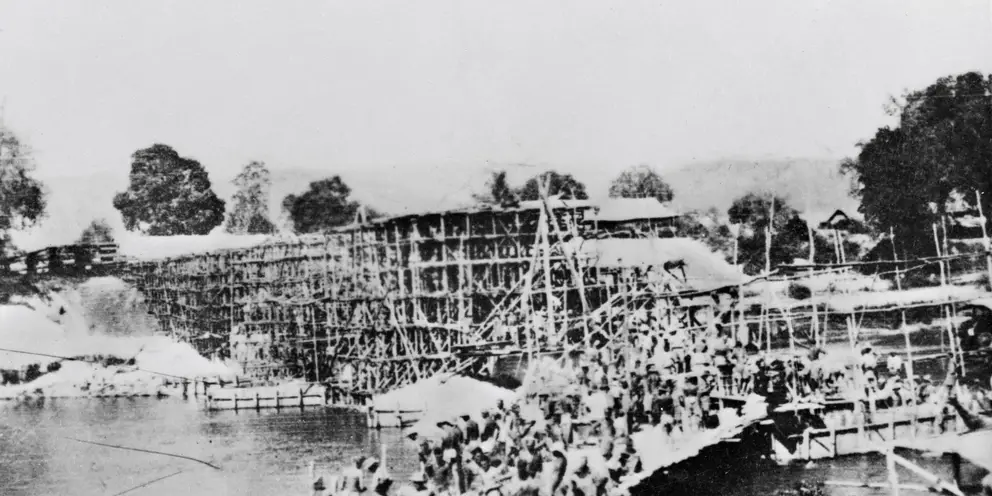

Allied prisoners of the Japanese building a bridge at Tamarkan which was completed in April 1943. Photographer unknown.

Those who did not die from overwork, illness and malnutrition gradually returned to Singapore as physical wrecks after they had completed the construction of the railway in late October. British Lieutenant Colonel Edward Holmes wagered that this story “would prove to be the outstanding event of 1943.” Captain Alan Rogers of the Australian Army Medical Corps went further and noted in his diary on 18 December that “a story like this will keep, I should think, for as long as there is history.”Captain Rogers was, in one sense, correct. The story of F Force has had a profound influence on popular memory of the Burma–Thailand Railway in Australia and Britain. Though other working parties on the railway suffered horribly too, the experiences of F Force made a crucial contribution to the project’s reputation as the ‘railway of death’.

F Force was raised in April 1943 in Singapore’s Changi camps as a working party destined for Thailand. Though they did not know it at the time, they were to become part of an ambitious project to connect the Burmese and Thai rail networks by building a new single-track line between Thanbyuzayat in Burma and Nong Pladuk near Bangkok. Preparations for the project had begun in early 1942 as Japan looked for a safer route to resupply its troops in Burma as the sea lanes were becoming more dangerous. Drawing on the large body of Allied personnel captured in 1942 , Japan began moving working parties made up of prisoners around the empire and in June some had already begun work on the railway. As the Japanese war effort became more desperate, completion of the Burma–Thailand Railway became a higher priority. Japan began to allocate more prisoners and romusha (Asian labourers) to railway work in both Burma and Thailand.

During 1943 new working parties arrived in Thailand to expand the labour force already in country. Their job was to extend the existing Thai rail network northwest from Bangkok towards Three Pagodas Pass near the Burmese border. Dunlop Force –900 men commanded by Colonel Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop – arrived from Java in January 1943; and D Force, made up of more than 5,000 prisoners from Singapore arrived in March. More were to follow, including F Force in April and H, K and L Forces over the next five months.

When F Force (the largest group of prisoners to leave Singapore) was formed in April 1943, Japanese commanders there misled British and Australian officers by promising that the new working party was to be sent to a place where food was more plentiful and sick men could recover. Since resources in Singapore were becoming scarce and daily routines had become tedious, the prospect of moving raised hopes among some of the prisoners. “We were agog with excitement,” recalled Sergeant Erwin Heckendorf from the 2/30th Battalion’s intelligence section. “We had become bored with the dull routine of POW life at Changi. Five groups had left the camp during the past few months to go up country or to Borneo and now it was our turn.” Others remained far more sceptical, and some were openly reluctant to leave.

Setting out

After some back-and-forth with the Japanese, F Force was assembled, with Lieutenant Colonel Charles Kappe in command of the Australian contingent (3,666 men) and Lieutenant Colonel S.W. Harris in charge of the British (3,334 men). The group was, however, already in a weak state – particularly the British. Lionel Wigmore, in the Australian Official History, estimated that 125 of the Australians were unfit but as many as 1,000 men of the British contingent (approximately 30 per cent) were already sick. To make matters worse, many had received only one of two rounds of inoculation against cholera before they departed.

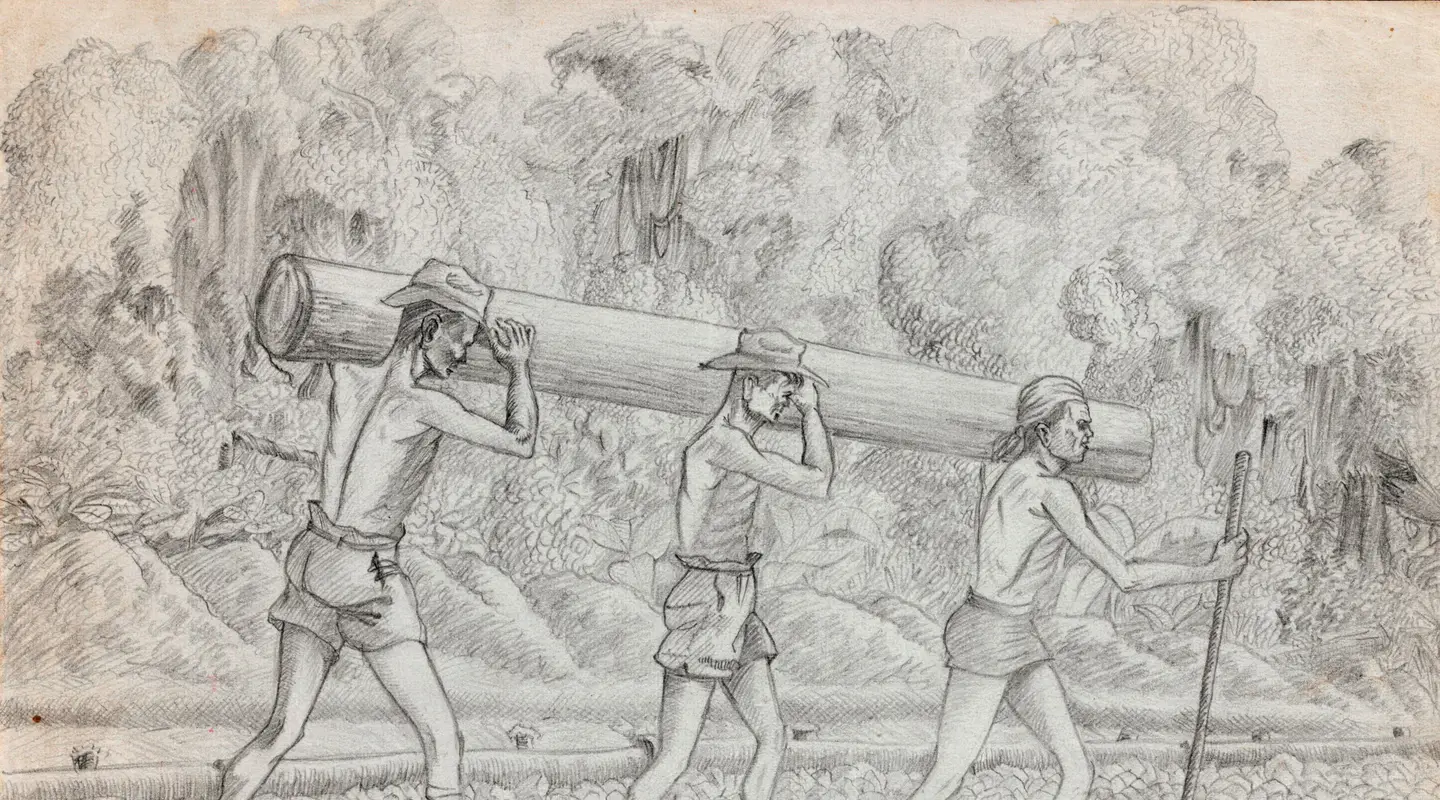

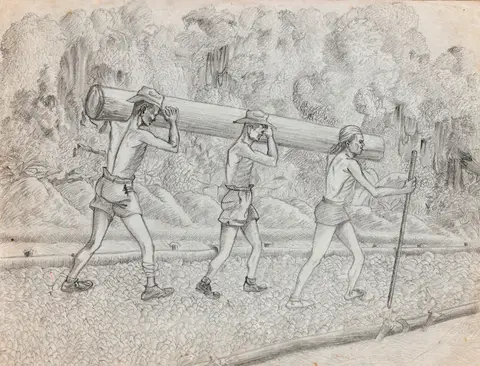

Artwork of three men carrying railway sleepers. James French, Sleeper laying party, c.1943

The first of 13 F Force trains departed Singapore on 16 April. The trains transported the men in steel rice trucks, each typically carrying 27 or 28 men in crowded and uncomfortable conditions; there were no seats, no toilets and few provisions. Those that had believed promises of respite also carried a surprising array of belongings, including trunks and a piano.

The trains travelled north from Singapore through Malaya and Thailand for five days before arriving in Ban Pong, 70 kilometres west of Bangkok. Some men later recalled that when they arrived, “the huts and adjoining area were in a filthy condition and the stench from insanitary latrines was overpowering.”

Here any remaining hopes for rest or recovery were finally crushed.

After enough men had reached Ban Pong, the Japanese began to assemble them into smaller groups for a march of as much as 300 kilometres to camps distributed along the planned route of the railway. Abandoning many personal possessions, the first group departed Ban Pong on foot in late April and began arriving at their camps 17 days later. As they moved up country, the jungle became thicker, the terrain more mountainous and the camps more remote. Before the last men had reached the camps, cholera had already begun to spread, and some never reached their destination.

F Force established a headquarters at Nikke but most of the men were distributed through several main camps including Kami [upper] Songkurai, Songkurai, Shimo [lower] Songkurai, Konkoita and the furthest camp, Changaraya. When they arrived, their squalid camps were a series of simple bamboo huts that provided only the most basic protection from the scorching heat or, with the coming of the monsoon, torrential rain. Maintaining daily routines became essential. The prisoners did their own maintenance and cooking, and their own medical teams cared for the growing number of sick men.

Speedo

From these camps the men of F Force began the grim task of completing the railway. Construction in these mountainous areas was among the most complicated of the entire project. The Japanese engineering teams were now under intense pressure to open the line as soon as possible, so daily work quotas were increased. One Japanese engineer, Yoshihiko Futamatsu, recalled the dismay among his comrades when their orders to speed up construction had arrived. “When they heard the order,” he wrote in his post-war memoir, they were “astonished at such a reckless command and one after another stressed how impossible it was.” The demands of what became known to both guards and prisoners as ‘speedo’ – the reduced timeline for completion of the project – overshadowed all the work that F Force and the other working parties completed during the final stages of finishing the railway.

To organise the work, officers were given orders each morning to arrange labour parties. These varied in size and purpose, depending on the location of the camp, how many fit men were available and what obstacles lay in the railway’s path. Work could involve sourcing timber from the jungle or cutting through a rocky embankment with shovels and hoes to level out the route for the tracks. Other men might be required to build bridges (688 in total) or lay sleepers, rail tracks or ballast. The tasks were diverse, but for F Force the labour was always gruelling, since heavy machinery was rare – it was simply too difficult to transport and repair. Some men managed to capture the work vividly in secretly-drawn sketches, such as those produced by Gunner James Joseph French of the 2/10th Field Regiment.

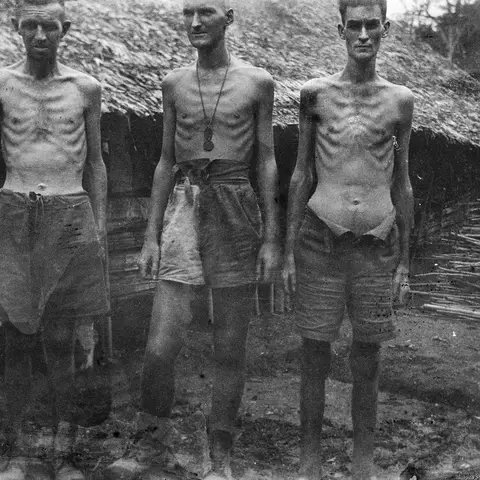

Three workers at Shimo Songkurai No. 1 Camp. They are believed to be Privates Bruce Pearce, Oscar Jackson and Reuben Pearce, all of the 2/30th Battalion. Photographer: George Aspinall (who secretly photographed his experience as a prisoner of war)

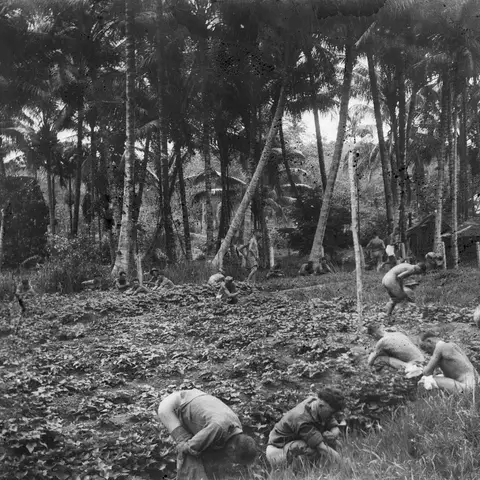

Members of F Force suffering from dysentery relieve themselves during a break in their journey to work on the Burma-Thailand Railway. Photographer: George Aspinall (who secretly photographed his experience as a prisoner of war)

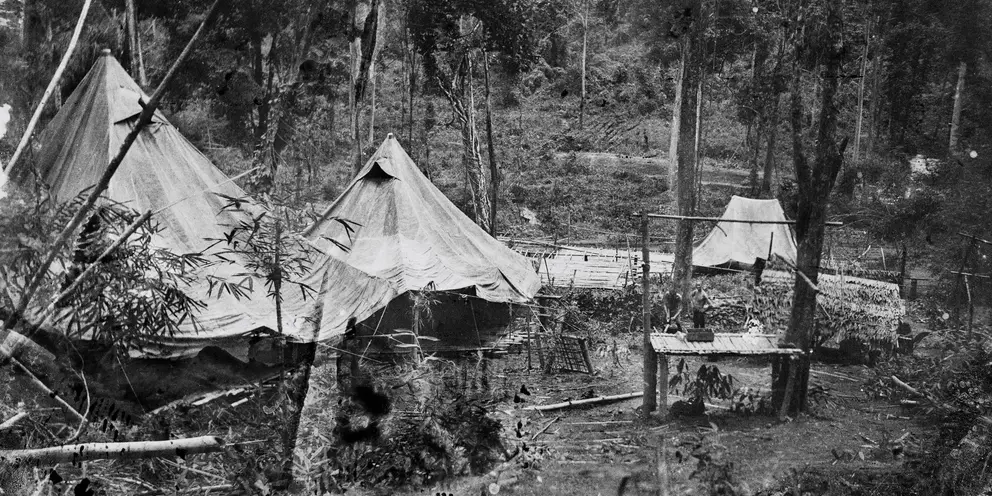

The isolation hospital for member of F Force at Shimo Songkurai No.1 Camp, known as Cholera Hill. Photographer: George Aspinall (who secretly photographed his experience as a prisoner of war)

The construction work was made infinitely worse from June, as the health of the men deteriorated rapidly. Though there were many common afflictions, cholera was the most severe, as it could kill in a matter of days. Private Cliff Bayliss of the 2/30th Battalion was reported as diagnosed with cholera at Kami [upper] Songkurai on 1 June and was dead two days later. In his diary, Lt Andrew Hyslop, Bayliss’s friend and fellow-school teacher, described his death as a ‘bitter blow’ and drew a small map locating the grave where he was buried. Cholera killed 571 members of F Force in May and June 1943 alone.

Those who escaped cholera faced malaria, beri beri, dysentery, tropical ulcers and other conditions, some captured in the rare photographs taken by Private George Aspinall. By the end of June, an estimated 46 per cent of all prisoners at Shimo [lower] Songkurai were suffering from malaria and 38 per cent from dysentery. In total, some 72 per cent of the all the men at Shimo Songkurai were incapacitated due to illness.

The declining health of F Force placed a terrible physical and psychological strain on officers and medical staff. Those working in the makeshift hospitals operated with inadequate supplies at extreme risk to themselves. After the war, Reg Jarman, a medical orderly from the 2/10th Field Ambulance, recalled:

Medical orderlies would be up before daybreak to collect the half-ration of food for the sick and dying in the hospital hut. They would feed those who couldn’t feed themselves and clean up all the mishaps from dysentery patients who couldn’t make it to the latrines. Two orderlies would remove all who had died during the night to an outside area. The daily average was four-plus, but I can remember one day when the death count was ten men.

Many survivors later remembered the doctors and medical staff as the true heroes of the railway.

Every prisoner, irrespective of rank, suffered from malnutrition. In part this was because the Japanese empire’s resources were under extreme pressure by mid-1943. It was also because the F Force camps were furthest from the existing rail hubs and larger towns in Thailand and Burma, and all the roads leading to the camps were dirt and had become a boggy mess when the monsoon began. In many cases, ration-carrying parties were the only way to get food into the camps – usually basic staples such as rice, beans and small amounts of meat. These deliveries could be exhausting, as Lt Clive Henry Moore of the 2/26th Battalion recalled:

On 14 June a party of nine officers and seventy-one other ranks left [Shimo Songkurai] with eight Yak [buffalo] carts for rations … which meant a haul of 13 km each way, the whole trip was a nightmare and some of the bogs were unbelievable, at one stage it took us one hour to move 500 yards … [After arriving] we loaded up with supplies and left for the return journey at 1700 hours, the trip back was even worse on account of the load and we were pulling carts like beasts of burden; we finally arrived back at Shimo Sonkrai at 0230 hours in the morning with 10 bags of rice, 2 bags of onions, 2 salt and 3 of beans which was about two days rations for the camp.

The only opportunities to supplement their diet came from slaughtering wild animals such as snakes and buffalo, or by buying additional food from local Thai or romusha camps when it was available.

Despite the immense odds, the 415 kilometres of rail between Thanbyuzayat and Nong Pladuk were joined on 17 October 1943 at Konkoita, Thailand, where a ceremony was held eight days later to celebrate the project’s completion. In part due to its rapid and shoddy construction during the speedo period, the railway only ever reached a maximum transport capacity of 500 tons per day, far short of the 3,000 tons the Japanese had originally planned.

Return

From November 1943, survivors of F Force began returning to prison camps in Singapore. Those who had remained in Singapore had some warning of F Forces’s devastating losses, but they were unprepared for the shock of seeing the survivors when they returned. According to Stan Arneil, who worked with F Force and later wrote about his wartime experiences in a popular memoir, a ‘great crowd’ of prisoners gathered on the road into Changi as the first 500 members of F Force approached. They looked like ‘silent corpses’ and climbing down from the transport trucks proved a ‘slow and ghastly business’. In Arneil’s account, when Australian commander Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Galleghan asked where all the men were, he was told, “All present and correct, sir.” Galleghan, who had a reputation as a tough and domineering commander, then walked through the lines of men with “tears streaming down his face”.

Building a bridge along the Burma-Thailand Railway. Photographer unknown.

In total, of the 62,000 Allied prisoners of war used on the Burma–Thailand Railway, 11,979 died – an overall death rate of 19 per cent. With a total death rate of 44 per cent, F Force clearly suffered far above average for the prisoners. Overall numbers, however, only ever tell part of the story. Within F Force, very few officers died (among Australian officers, approximately 1 per cent). Though many were conscientious, officers were paid at a marginally higher rate, were given preference for shelter, and they were not required to perform manual labour – all of which made enough difference to improve their chances of survival.

In F Force, there was also a major disparity between the British and Australian death rates – 61 per cent of British prisoners in the force died compared with 29 per cent of the Australians. One reason for this was that there were more unfit British men in F Force when they departed Changi in April, leaving them more vulnerable to cholera and other diseases. It should be noted, however, that the death rate of British and Australian prisoners across the entire railway were similar – 22.9 per cent among the British and 21.5 per cent among the Australians – making the figures for F Force something of an anomaly.

In popular imagination the ‘warrior code’, allegedly embedded deep within Japanese military culture at the time, is often taken as a key explanation for the suffering of prisoners in the Asia–Pacific theatre and on the Burma–Thailand Railway. While the code certainly contributed, it is far from a sufficient explanation and it fails to make sense of the vastly different death rates among prisoners spread across Japan’s 384 camps during the war. To take two extreme examples, the 2,500 Allied prisoners at Sandakan in Borneo suffered a 99 per cent death rate but only 0.1 per cent of the 87,000 prisoners rotated through Changi in Singapore died there during the war.

Better explanations for F Force’s exceptional attrition lie in the circumstances of their deployment during 1943. Moving men into remote Thailand was a logistical challenge, compounded by the fact that Japanese authorities in Thailand and Malaya had to share responsibility for the men in an unnecessarily complicated arrangement. The Japanese engineers were also rushed to finish the railway, and so placed ever-increasing pressure on the workers, pushing many beyond their limits amid an outbreak of cholera and the monsoon. The callous attitude of some camp guards did nothing to alleviate the appalling conditions. After the war, five Japanese and two Koreans were charged with war crimes directly related to the treatment of F Force.

The story of F Force was not the only story of the Burma–Thailand Railway. It says little, for example, of the fate of the romusha (perhaps as many as 180,000 people) who made a crucial contribution to the project and who died in far greater numbers than Allied prisoners of war – a death rate some have estimated to be as high as 50 per cent. What happened to F Force does, however, offer some insight into why the Burma–Thailand Railway was so traumatic for many prisoners who survived and left an account of their ordeal.