Neil Davis lived on his instincts to produce startling footage of wars in Asia.

The legendary news cameraman Neil Davis would not have expected to die on 9 September 1985 in Bangkok, but colleagues who knew him were not surprised to learn that he had actually filmed his own death.

That day Davis was planning to travel to the Cambodian border, to help his former driver in Phnom Penh, An Veng, start a new life. But before he could leave for the border, he was told by his employer, American network NBC, to cover one of Thailand’s military coups. These were usually fairly gentlemanly affairs, with the losers allowed to leave the country and return discreetly some months later.

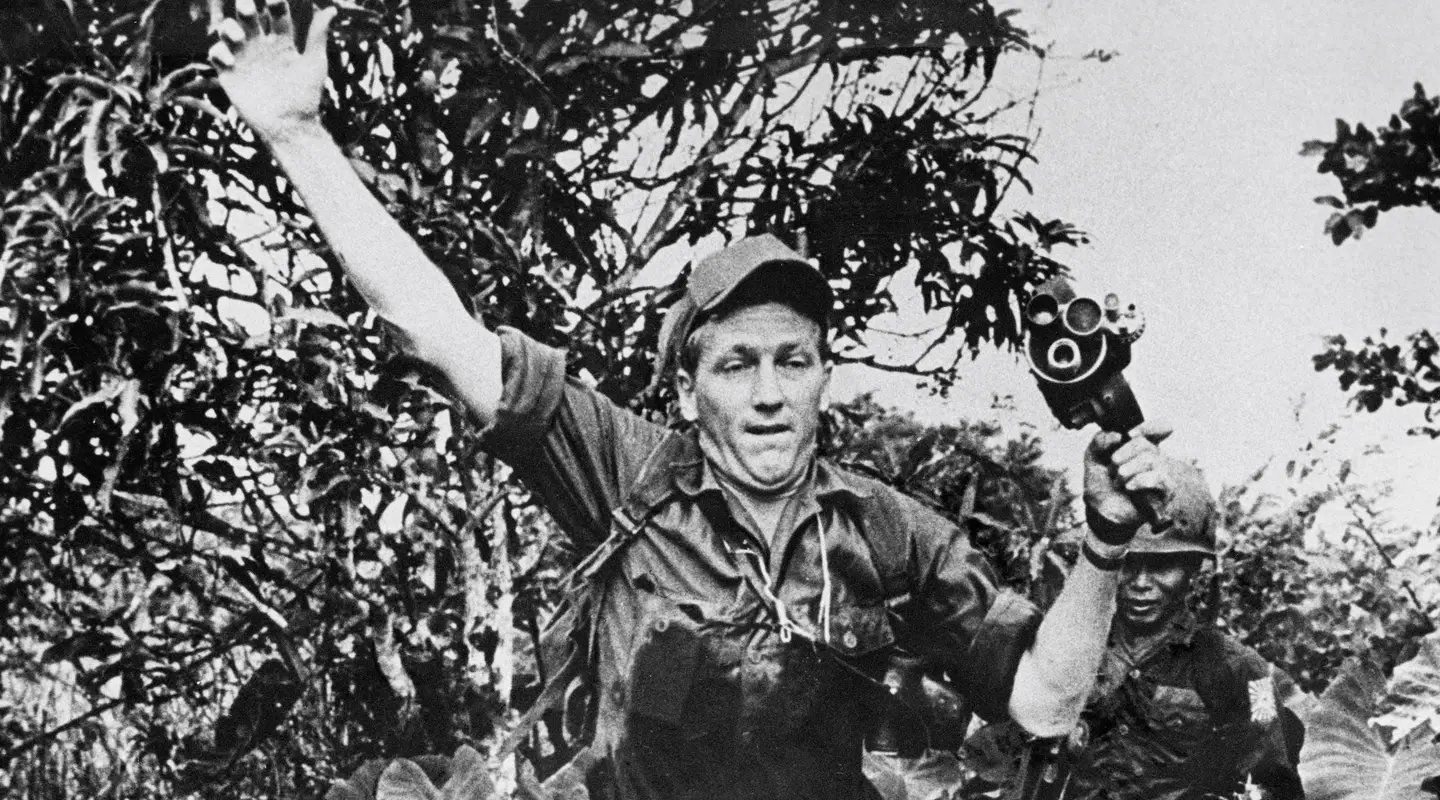

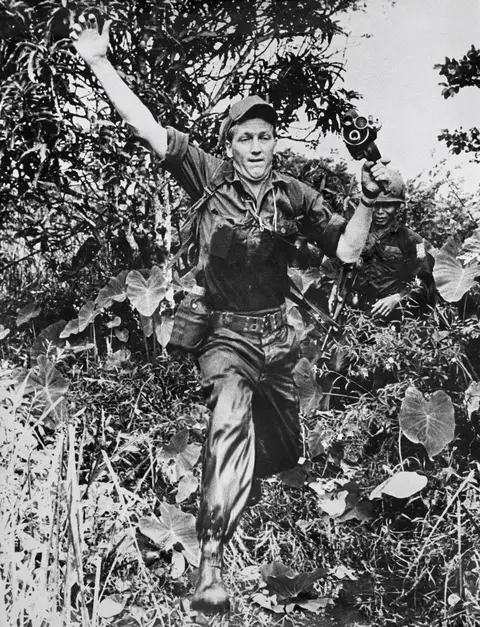

Neil Davis leaps through the jungles of South Vietnam with his hand held Bell and Howell camera c. 1967. Photographer: Peter Arnett

Davis had spent the preceding 11 years covering frontline combat in Vietnam and Cambodia for the international agency Visnews, and had only joined the American television network NBC shortly before the war ended in 1975.

During most of that time he had worked alone, filming combat with a hand-held clockwork Bell & Howell camera, and recording sound with a cassette recorder strapped to his waist. He liked to work alone, as he had great faith in what he called his sixth-sense anticipation in dangerous situations.

But in 1985 modern technology had him working with his nine-kilogram video camera yoked to a heavy battery and cassette pack, carried by his soundman, Bill Latch, whom he joined in Bangkok’s busy Phitsanulok Road where rebel soldiers had occupied a radio station.

Neil’s Australian friend, cameraman Gary Burns, joined him, and they had no warning when a machine-gun opened fire. According to Burns they grabbed their gear and ran in search of cover.

“Unfortunately my soundman ran the wrong way, to the left, in front of three tanks. If we’d run to the right we would have been clear of the tanks and the soldiers very quickly.”

Davis stayed between two phone booths to film the firing. Taking what cover he could, Burns looked along the road to see Davis up on one knee and filming. “I thought, oh shit, if he’s filming, I’ve got to film.” He poked his camera out, but still behind cover. During a brief lull before the tanks opened up with their cannon, Davis and Latch ran over to join Burns behind a small metal junction box. All hell broke loose from machine-guns, tanks, cannons and soldiers with automatic weapons. The four men, yoked in pairs with camera gear and cables, were desperate for cover, crammed in behind the junction box, barely a metre wide, as the soldiers fired directly into the gate of the radio station and the wall behind the camera crews.

Burns was unbelieving as he saw Davis preparing to film again, even though the machine-gun bullets and cannon shells were screaming overhead and exploding against the wall behind them. It was utter pandemonium. The street filled with smoke. Burns could feel Davis lying half across his body. He felt they were all going to die. During a lull, soldiers on a tank gestured towards the news crews to get out of there. He didn’t feel Neil get hit. He recalled:

Always the complete professional, Neil Davis had filmed his own death. His head, astonishingly almost in focus, appeared in front of his own lens as Burns, at enormous personal risk, tried to pull him away, Davis’s still-rolling camera tilted over on its side. His mortally wounded sound man, Bill Latch, hit in the stomach and legs, was filmed desperately crawling away as Burns attempted to rescue his friend’s body. Davis’s camera also showed tank cannons still inexplicably firing, seemingly at them. Other cameras showed the ghastly blood trail from Davis’s terrible wounds staining the tarmac as he was dragged away by Burns.

Into Vietnam

In Sydney, unaware of what was happening in Thailand, I had started writing Davis’s biography with a quote from our interviews, the very first in my book One Crowded Hour. “I wasn’t afraid of being killed, but I really didn’t want to be wounded and lie out there with a gut full of shrapnel – I’d seen a lot of wounded soldiers die like that, and I didn’t care for it at all.” The irony of beginning his life story on the day he died would have amused him.

I did become addicted to combat after experiencing my first three years in Vietnam. It was exhilarating, much the same as playing a good hard game of football … I was apprehensive many times and very excited, but when I got used to it, I used to look forward to combat ... I felt very confident I could handle any situation, partly because I developed an extra sense – instinct if you like – which a wild animal has and which we have lost in our so-called civilised life ... On occasions I have instinctively dropped to the ground before a shot was fired.

When Davis first arrived in South Vietnam in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson was committing 500,000 United States troops to prevent, he hoped, a communist takeover from North Vietnam. Saigon was also being flooded with an American press corps, so Davis decided to cover the conflict by going out with the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN). He realised they were already doing the major share of the fighting, suffering heavier casualties than the US troops.

Davis on patrol with South Vietnamese troops in Mekong Delta c.1972

Neil was the only Western correspondent to go out with the ARVN, which meant there would be no helicopter evacuations available if he was wounded, and he would have to eat their rations and drink water from rice paddies. He would often have to stay out in the field for four or more days. He conversed easily with the ARVN troops in a patois of French, English and whatever Vietnamese he had picked up, plus a great deal of body language.

He was 30 when he won the Visnews job in South Vietnam. He had done his apprenticeship with the Tasmanian Government Film Unit, learning to be economical with film, an expensive commodity even in black and white 16 mm, and learned to craft a story in the camera so minimal editing would be required. These skills proved invaluable when covering combat in Vietnam with a hand-held spring-loaded Bell & Howell. “Thirty-five-millimetre film was terribly expensive and the edited news clips [for cinemas] ran for less than a minute. We were expected to cover a story using only 100 feet of film with a running time of two minutes forty seconds.” In Vietnam Davis was bemused to see US cameramen chew through more than one 400 ft film cannisters for what would finish up as a short news clip.

The Americans were wrongly contemptuous of the fighting abilities of the ARVN troops, and referred to them in racist terms as gooks, dinks, or slopes. By 1970 approximately 2,000 anti-communist soldiers were being killed a year. Neil noted in a letter that 1,800 of them were Vietnamese, and only 200 were American.1 It was inevitable that that some of these deaths would occur in front of Davis’s Bell & Howell camera.

Neil Davis on assignment at Aranya Prathet during Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia circa 1979

“Most Westerners tended to forget that the Vietnamese soldiers on both sides were nice, simple people with ordinary human thoughts and desires. I tried to bring out this human element whenever possible,” he said. One of his favourites was Nguyen van Phuc, known as “the grenade thrower”. He would take off his heavy flak jacket and military gear, put a cluster of hand grenades in a plastic shopping bag and crawl forward in his pants and shirt to within a few metres of a machine-gun post to knock out the position.

On this occasion Phuc was aiming to knock out a North Vietnamese unit taking cover in a cemetery. Neil gained some superb film of Phuc who, as expected, stripped down to his pants and T-shirt and while the rest of his unit covered him with their fire, he wriggled forward to lob his grenades into the North Vietnamese machine-gun positions. Late in the day Phuc made his third and final sortie, using one of the tombstones as cover.

He actually scampered the last three metres very cockily. He thought he had killed all the attackers and made his one fatal mistake. [Back in the lines] he stood up to put his heavy flak jacket back on. I was half-lying behind a tree and Phuc stood in a shallow trench, laughing and excited. A burst of automatic weapons fire came in, and I ducked my head.

When I looked up again at Phuc I could see that he had been hit – stitched right across his body with bullets. He said just one word, chet, which means “dead”, and then he fell forward. I suppose it was a reflex action, but I kept running my camera. I knew I had film of this laughing young man displaying the joy of life as he knew it just an hour before – and I hoped that if I showed the shock of him suddenly dying, it would impress on people at home very graphically what it was like to be a common soldier out there, no matter what side he was on.

Phuc lifted his head, his eyes went out of focus and it was obvious he was dying quickly. He died with dignity and quietly slumped forward about ten seconds later without another word.

This film received enormous praise when it was shown, but Davis thought that Visnews and the audience had missed the point, just seeing it as some film taken in unusual circumstances, and not as he hoped: a story to bring home on a personal level the awful reality of war. As he later wrote to his confidant, Aunt Lillian in Tasmania, “However, it’s done, and there’s little doubt I would ever do it again.”

Open war

When Lyndon Johnson began introducing half a million men into South Vietnam, there was an unshakeable confidence that they could do the job. It was also the Amercians’ first, and last, open war – when anyone who wanted to (journalists, writers, do-gooders) could be accredited by the United States to go where they wanted on military transport, photograph and film what they wanted – all in the interests of the fight against communism.

When I went there for the first time in 1965, Neil Davis met me at the airport and took me to the US Military HQ to be accredited with the notional rank of a lieutenant in the US Army as a correspondent for the ABC. This would allow me a seat on any military helicopter or aircraft and I could notionally bump a lesser rank if there was no room for me. Not that I ever did. Neil also made sure I was accredited with the South Vietnamese Army that same day.

The concept of an open was war not a good idea, particularly when the conflict in its later years was not going well for what the Americans called the “free world forces”. The first and biggest shock for the Americans was when Tet erupted in 1968 (see Wartime 92). Things were never the same after that, although the Viet Cong paid dearly in casualties and North Vietnam effectively took control of the insurgency from that moment.

Davis carries a wounded Cambodian soldier out of action on his back, 1971. Photographer unknown.

Davis on a stretcher after being injured by a mortar blast in Cambodia, 1974. Photographer unknown.

Two specific incidents soured public opinion in the United States during this increasingly unpopular conflict. The Vietnam war’s most coldly brutal images were filmed (by Vo Huynh, a South Vietnamese cine-cameraman) and photographed (by Eddie Adams of Associated Press) and went viral all around the world. The first showed Saigon’s Chief of Police, General Loan, shoot a Viet Cong prisoner in the head in cold blood in the street. (Loan had just heard that the Viet Cong had murdered his best friend, a police colonel, and his wife and six children. The children had their throats cut.)

The other public relations disaster was the shocking image of a nine-year-old girl, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, who had run naked from an aerial napalm attack on a village, her clothes burnt from her tiny body and her skin peeling off as she screamed in agony. The photo was taken by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize. (She survived, and after a period of bitterness and hatred over what had happened to her, converted to Christianity.)

In 1975, near the end of the war, Neil Davis decided to remain in Saigon and wait for the communist takeover. There were other cine-cameramen in the grounds of the Independence Palace when the leading North Vietnamese tank smashed through the palace gates. But only Neil was game enough to raise his cumbersome sound camera to his shoulder (which might have been mistaken for a weapon) and film until a North Vietnamese soldier jumped from the tank, ran towards him and knocked the still rolling camera off his shoulder. But in those frenetic few seconds, Neil alone had filmed the end of the Indo-China war.

The other toll

In the course of that war from 1965 to 1975, an estimated 70 journalists were killed in action. These included journalists from North and South Vietnam as well as journalists from Japan, Singapore, India, Laos, and Cambodia. Western journalists, men and women, came from America, Britain, Australia, Germany, France, Argentina, Holland and Switzerland.

But none of these was targeted by the enemy, and their deaths can be summarised by the euphemism of “collateral damage”: being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Some were experienced war correspondents, others worked for established news, radio and television organisations; there were writers of all kinds and freelancers. Anyone could cover the Indo-China war if they wanted to. The United States would never again be involved in a conflict that was such a free-for-all. In future major wars involving US forces in the Middle East in the latter part of the 20th century, journalists would be “embedded” with fighting units so the Army could restrict their access to action, and censor their copy. It would not be long before uncensored war-related images and stories would be powerful influences on public opinion, as in the Balkan wars of the 1990s.

But since the end of the Indo-China war in 1975, the press was likely to be deliberately targeted by the perpetrators to prevent such stories getting out and being shown to the world. I now believe that Neil Davis died as a result of the pro-government forces deliberately targeting the unwanted attention from Western news crews filming their attack on the rebel radio station in Bangkok in 1985. Since then the philosophy of “shoot the messenger” has been all too prevalent in conflicts around the world.

The last word comes from Neil Davis, on his own chances of survival as a chronicler of combat: “But of course a sense of instinct doesn’t stop a well-aimed bullet … you can always be killed … unluckily killed.”'

1 Nearly 30,000 anti-communist troops lost their lives in South Vietnam in 1970.