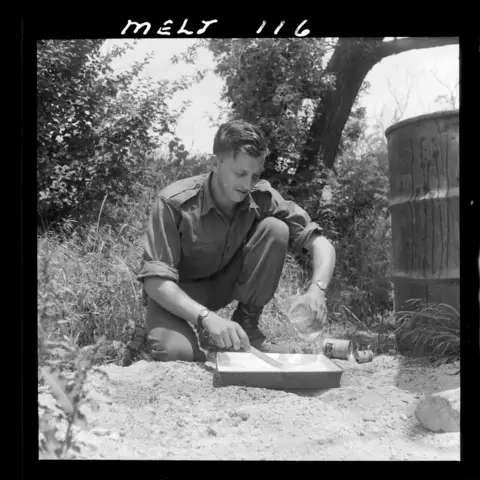

War zone Korea posed difficulties for photographers who shot and developed their film in situ.

The realities of working in a war zone in Korea understandably posed difficulties for photographers who shot and developed their film in situ. Undeterred by the logistics involved in procuring film, developer and equipment, and often operating under harsh conditions, men of the Australian battalions took up photography with enthusiasm.

Informal portrait of 31932 Private Ian 'Robbie' Robertson, 3rd Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment

31932 Sergeant Ian ‘Robbie’ Robertson was already interested in photography before serving in Korea; he explained that all one really needed was “a box camera and a backyard”. Robertson became a sniper and unit photographer for the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3RAR), commenting, “Everywhere I looked there was a photo.” Often with a .303 Lee-Enfield rifle in his hand and a large Zeiss Ikoflex Ikon twin-lens camera around his neck, Robertson described taking photographs while in the line: “You’re in action and then there’s a sudden lull … you’ve just got to take a chance on it.” Behind the line there was more time to deliberately compose an image of the men traversing the Korean landscape, or locals attempting to go about their lives despite the conflict. Here Robertson’s love of art became evident in his keen eye for composition.

Despite the element of added risk, designation as a unit photographer typically came without any additional pay. Robertson’s solution was to employ a papasan to print his photographs while he was on leave in Japan, before on-selling the prints to his fellow diggers for a shilling each. This covered the cost of ordering more film, which could be delivered via mail. The affordability of good quality cameras and equipment in Japan also helped to maintain this hand-to-mouth routine.

Sergeant Ian Robertson on being a sniper and unit photographer

I had a camera at home, but I didn't use it and film was short throughout the war. So, you know, my experience as a photographer was really limited, you know.

I became a battalion photographer for a few months before we went to Korea.

I became a sniper. They said, oh, well, we don't need a photographer there really. They just ignored that fact. And so, but I took two cameras over there with me.

I was a sniper first and a photographer second. And it's got to be that way too.

When there's bullets flying, you can't think of taking photographs then. You've just got to shoot back.

You're in action and then there's a sudden lull or there's something where I'm behind cover and I look around, there's a photograph.

Bang, you know. And there was a film that I lost forever on 35mm. Everywhere I looked, there was a photo.

[partial] oral recording of Ian Robertson, 26 March 2007 AWM S04271

3RAR arrives in Pusan, Korea, 1950. Ian Robertson

Members of the Intelligence (or Sniper) Section sit in a shallow trench after capturing Hill Salmon from the Chinese, April 1951. Ian Robertson

Members of C Company, 3RAR led by Corporal Len Wright (left) move forward from Hill 614 to attack Hill 587. Ian Robertson

“Everywhere I looked there was a photo.”

Sergeant Ian Robertson

An unidentified member of 3RAR using a cinecamera. Ian Robertson

Korean refugees trudges along a dusty road away from the war. Ian Robertson

Private Chris Bell-Chambers, 3RAR, smiles and waves to a group of Korean children. Ian Robertson

For men who did not want to wait for leave rotations, the task of developing film in the field took some resourcefulness. 13018 Private John ‘Dogger’ Dick was a station hand, drover and amateur rodeo rider from Wynnum, Queensland. He, too, had taken up photography before enlisting, and naturally inherited the role of unit photographer. In an image from June 1954, Dick is pictured diverting water from a mountain stream into a tub to wash his negatives. Such streams would freeze over during winter with temperatures below zero, making developing outdoors extremely unpleasant, if not impossible.

Dick’s medium-format photographs contributed to a large photographic album compiled by members of 1RAR, which was reportedly almost four feet long and three feet wide (about 120x90 cm). Under Dick’s mentorship, 1RAR formed a camera club and erected and operated their own darkroom, as more men took up photography during their second deployment in Korea (March 1954 to March 1956) after the war had officially ended.

By 1954 British Commonwealth Forces Korea (BCFK) Public Relations observed of 1RAR that “hundreds of soldiers have become keen shutterbugs.” While the BCFK affectionately suggested that for some men their enthusiasm outweighed their skill with a camera, snapshots taken by seasoned photographers and so-called shutterbugs alike provide an engaging glimpse into life on the 38th Parallel.