How the military has contributed to Australia’s policy of assistance with natural disasters in our region.

Just before 8 am on 26 December 2004, a 9.1-magnitude earthquake, one of the largest on record, caused a displacement of the sea floor off the west coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, creating a series of giant waves, a tsunami. It smashed into coastal areas bordering the Indian Ocean, causing widespread destruction and the death of up to 230,000 people in 14 countries. Aceh in northern Sumatra was one of the worst affected areas, with a death toll of more than 160,000 and extensive damage to infrastructure around its capital, Banda Aceh. More than 500,000 people were left in need of food, water and shelter.

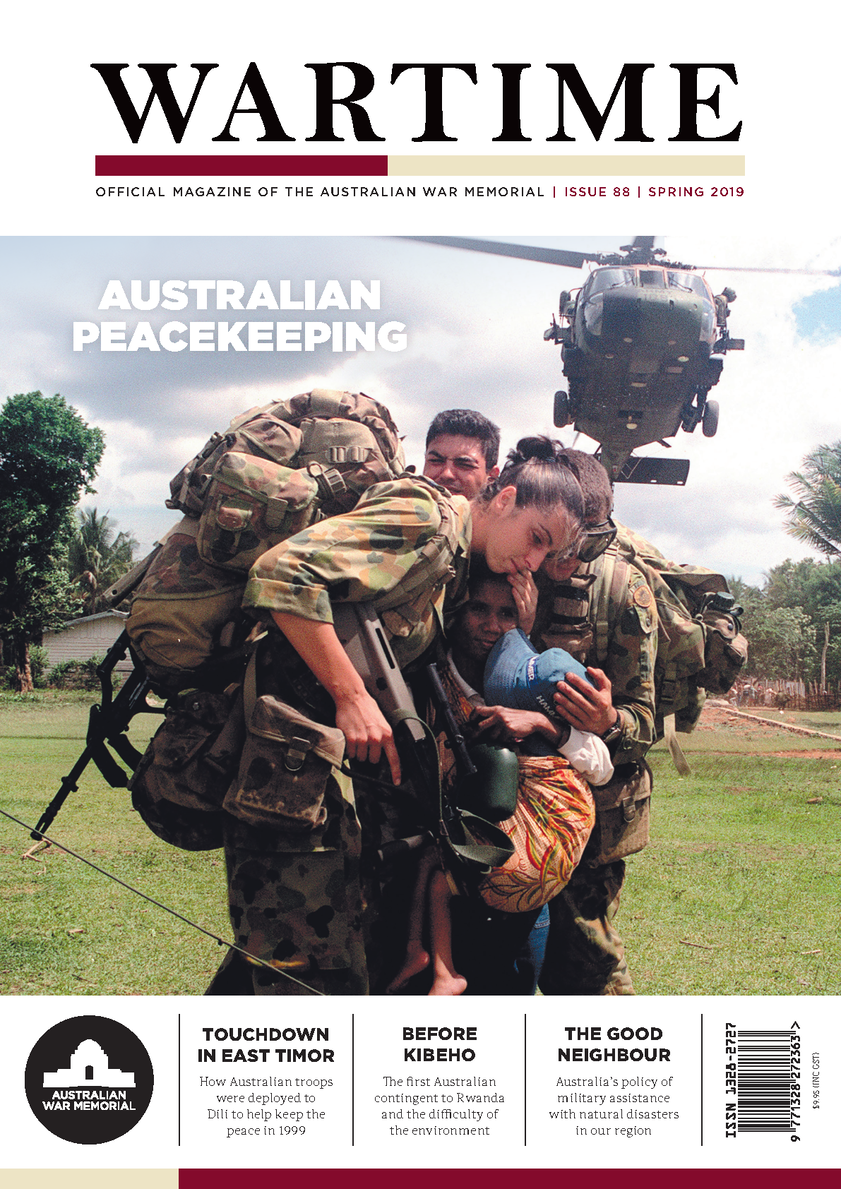

Devastation after the tsunami hit Banda Aceh. Photo: Ben Bohane.

As part of the Australian response to such an unprecedented disaster in the region, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) contributed approximately 1,100 personnel over a three-month period in what is still the ADF’s largest-ever overseas disaster relief mission. This response included an Army field hospital to supplement stretched local health services; Army engineers to provide purification of water and clearance of roads and drains; a detachment of Army Iroquois helicopters to transport displaced persons and relief supplies; several Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) C-130 Hercules aircraft to evacuate casualties and transport humanitarian supplies; and an air traffic control team to assist at Banda Aceh airport, which overnight had become one of the busiest airfields in the world. The Royal Australian Navy’s HMAS Kanimbla transported the engineers and their equipment, and then remained in the region to provide medical and other logistics support for the land-based relief effort. Sea King helicopters on board Kanimbla transported supplies and personnel, supported by a range of other communications, logistics and headquarters personnel.

Since the 2004 tsunami, the ADF has contributed to numerous Australian responses to disasters in the region and further abroad. But it was not always the case that the ADF would so readily provide services of that kind. ADF involvement in overseas disaster relief is a relatively new phenomenon. It was brought on by developments in a range of domestic and international fields, by the direction provided by defence and foreign policies, and by trends in international relief and disaster management.

Early missions

The first Australian overseas disaster relief mission began in November 1918 with the transportation of an Army medical team in HMAS Encounter to provide assistance to the New Zealand military administration of Western Samoa, and to the British colonial authorities in nearby Fiji and Tonga. The islands were at that time suffering badly from the effects of the Spanish flu pandemic sweeping the globe, causing the deaths of as many as 100 million people worldwide. New Zealand, which requested Australian assistance, was not in a position to respond, as it was dealing with its own Spanish flu outbreak. Australia was free of the disease because of a strict quarantine regime; despite this, as many as 12,000 Australians would later perish at the hand of the “Spanish Lady”.

Inhalation of zinc-sulphate and daily “thermometer parades”, such as depicted here on the deck of HMAT Derbyshire in February 1919, were part of the strict quarantine regime imposed by Australia to keep out the Spanish flu.

The mission was undertaken because of Australia and New Zealand’s imperial connections to Britain, and it was enabled by the mobilisation of Australian armed forces immediately after the end of the First World War. While it was outwardly a demonstration of concern for the peoples of the region, the deployment was also an opportunity for Australia to press its case for a mandate over the former German territories in the Pacific. This was a goal of Prime Minister Billy Hughes, to increase Australian prestige and prevent Japanese expansion south of the equator (see Issue 87). Though the mission was successful in providing some assistance to local authorities and succour to victims of the disease, it was very much the exception that proved the rule: that the primary purpose of Australia’s military forces was the defence of the nation, not to assist the civil community through disaster relief.

As a result, aside from several limited responses to volcanoes in Papua and New Guinea (Australian overseas territories at that time), Australian military forces were not again involved in overseas disaster relief until January 1960, when a detachment of engineers was deployed to the New Hebrides (today’s Vanuatu) after a cyclone caused heavy damage to the capital, Port Vila. This unprecedented deployment originated in a request from the British administrators of the colony. They wanted a show of military force to counter the deployment of French troops from New Caledonia – reflecting a rivalry that stemmed from the unique dual British–French administration of the New Hebrides. The Australian deployment was also made possible by the acquisition of the first Hercules aircraft the previous year, which enabled the quick delivery of large quantities of material and personnel over the expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

In this period, several other factors prompted consideration of using military forces in this way. With the emergence of the Cold War, in the early 950s Australia sought to support non communist-aligned countries of the region through development projects, such as the Colombo Plan, and with financial grants after natural disasters. It was hoped that such assistance would encourage these countries not to adopt communism, and so prevent its spread through the region. While these financial grants did not include the use of Australian military forces for relief efforts, in this period humanitarian assistance began to be seen as bringing political and strategic benefits to Australia.

In response to Cold War tensions in the region, Australian strategy during the 1950s involved the deployment of Australian military forces to various locations in south-east Asia, which was known as the Forward Defence Policy. These Australian military forces, which were either already in or travelling to the region, were in a position to respond quickly after natural disasters in countries aligned with the West; this was a natural extension of the purposes motivating financial grants to these countries. Such thinking led to several Australian military contributions after floods and earthquakes during the 1960s and 1970s in Malaya, Thailand and Indonesia. Indeed, the engineer unit that deployed in 1960 on the first cyclone relief mission was already on short-notice readiness for contingencies in south-east Asia, enabling its quick deployment to the New Hebrides.

In Australia

Developments in the responses to disasters in Australia had an impact on overseas relief efforts. After a series of floods and fires during the early 1950s, RAAF aircraft, amphibious vehicles (so-called Army Ducks) and other military equipment and Defence personnel began to be used more extensively to supplement civilian relief efforts during disasters across Australia. Disaster relief was constitutionally the responsibility of the states, but the federal government could get around constitutional obstacles by providing the states with Defence personnel and equipment.

Those efforts culminated in the extensive responses to a series of devastating fires, heatwaves, cyclones and floods across the eastern states of Australia. The ten years from the mid-1960s were later known as the “disaster years” or “disaster decade”. In 1974 the new Whitlam government established the Natural Disasters Organisation (NDO) to coordinate the national response and provide assistance to the states after major disasters. The NDO was part of the Department of Defence, and a serving military officer, Major General Alan Stretton, was appointed as its first director-general – indications of the growing importance of the military in domestic disaster relief.

There was an unprecedented military response to the destruction of Darwin by Cyclone Tracy on Christmas Day 1974, just months after the NDO was established. The comprehensive response by the three armed services over the following three months included more than 3,000 personnel and seven fleet vessels from the Royal Australian Navy. Two contingents of approximately 650 personnel, with supplies and equipment, came from the Army; and the RAAF provided medical assistance and aircraft, which flew more than 1,600 hours transporting casualties, displaced persons and relief supplies.

But the increased importance of Australia’s military forces in domestic emergency relief was not yet matched by a role for Defence in responding to disasters overseas. By the mid-1970s Australia had abandoned forward defence in favour of a strategic policy of self-reliance – a move influenced by US and British declarations they would withdraw the majority of their military forces from south-east Asia by the early 1970s. Australia gradually came to realise that the country would need to rely more heavily on its own military resources for its defence, and thus Australia’s primary area of strategic interest had shifted much closer to home. In this changing strategic environment, in the second half of the 1970s there was a marked increase in development aid, diplomatic representation and defence cooperation programs to the nations of the South Pacific.

Darwin aftermath Cyclone Tracey 1974

A salvation army volunteer distributes food in Darwin following Cyclone Tracy in 1974. Photo courtesy National Archives of Australia.

In the region

These closer connections, and improving communication systems across the region, gave Australia a better awareness of the impacts of natural disasters in these areas. By this time, the role of the military in domestic disaster response had expanded, so there was a growing tendency to consider a similar military response to regional disasters. The first came after an earthquake and mudslides on Guadalcanal, in the Solomon Islands, in April 1977 left 12 people dead and thousands homeless; a RAAF Iroquois helicopter detachment was deployed for two weeks to deliver supplies. Over the next 15 years, the ADF was involved in another 18 similar relief missions to the nations of the Pacific. They typically involved the delivery of relief supplies by Hercules, often with Iroquois helicopters and Caribou aircraft for transport and distribution of supplies in affected areas.

Though assistance missions to the Pacific started in 1977, it was not till 1984 that it became Defence policy to use the military in this way. The government decided to expand the NDO’s mandate to include responses to disasters in the Pacific and the near region, as well as to emergencies within Australia. After one of the most destructive storms on record struck the Solomon Islands in May 1986, this new Pacific mandate for the NDO resulted in the largest overseas military relief effort by Australian forces to that date. Costing more than $5 million, the military response after Cyclone Namu included more than 600 Defence personnel, four RAN ships, RAAF helicopters and aircraft, a clearance diving team, and Army water purification and preventive medicine teams.

In addition to relief missions to the Pacific nations, Australian military forces were involved in responding to a further 14 disasters in Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and south-east Asia from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. After a peak of activity in 1993 and 1994, these missions became smaller and less frequent – primarily because of the growing cost of Defence involvement, and because of a decision to allocate the costs to the overseas aid budget. Pacific nations were also developing their capacity to respond to disasters with their own resources. This was partly a result of efforts in the 1990s by the international community and local governments during the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction, which aimed to reduce the effects of natural disasters before they occurred.

An Iroquois from 171st Command and Liaison Squadron delivering relief supplies to a remote northern island of Vanuatu, January 1992. The Vanuatu police patrol boat was provided by Australia. Photo: Paul Copeland.

The Keating Labor government also placed less emphasis on engagement in the Pacific, and focused more on promoting wider capacity and cooperation within the region. Defence Cooperation Programs were increasing, as was support for the Pacific Patrol Boat Program; from 1987, Australia provided 22 patrol boats to 12 Pacific nations to improve their maritime surveillance. At the same time, reflecting the international optimism brought on by the end of the Cold War, Australia was involved in a series of large international peacekeeping missions to Namibia, the Gulf, Cambodia, Somalia, Rwanda and Bougainville; these further reduced Defence’s limited capacity to respond to disasters in the region.

Ater it was elected in 1996, the Coalition government led by John Howard undertook a comprehensive review of Australia’s strategic and diplomatic situation, with a foreign affairs white paper, In the national interest, and Defence’s Australian strategic policy. Both these documents emphasised that Australia’s security and economic interests were intimately linked to the security and stability of the Asia–Pacific region, with a special place for Indonesia as Australia’s largest neighbour. These policies also reflected the government’s cautious approach to multilateral solutions in international affairs. This was partly a reflection of Howard’s bias against the United Nations and partly a result of disillusionment with peacekeeping after the tragedies in Rwanda and Bosnia earlier in the decade.

The Howard government’s desire for social and economic stability in the region was demonstrated by Australia’s response to the widespread drought and famine brought on by an extreme El Niño weather event in 1997. Papua New Guinea and Indonesia were hardest hit. The situation in Indonesia was made worse by widespread wildfires, the disruptive impacts of the Asian financial crisis, increasing unemployment, and a growing disaffection with the ruling Suharto regime. Australia’s response to the crisis included a $1 billion contribution to the international financial bail-out for Indonesia. Australian military aircraft and personnel also deployed to both countries for a total of 11 months in 1997 and 1998 to assist local authorities and other agencies to distribute famine relief supplies.

After 9/11

Australia’s strategic situation (and the world’s) changed radically as a result of the terrorist attacks against the United States on 11 September 2001. Australia contributed to the “coalition of the willing” to defeat the Taliban in Afghanistan, and joined the United States in 2003 in the controversial deployment of troops to Iraq to remove Saddam Hussein and his capacity to produce weapons of mass destruction. The presence of Australian military forces in the Middle East (characterised by the government as support for wider interests in the post 9/11 world) led the government to consider the first disaster relief missions outside south-east Asia and the Pacific. These included a one-off delivery of relief supplies to Iran after the Bam earthquake in 2003, and the contribution of a medical team and helicopter detachment to the international response to the Kashmir earthquake in 2005.

Australian medics assisting at Camp Bradman, Pakistan, after the 2005 earthquake. Photo: Gary Ramage.

The rise of international terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and failed states as breeding grounds for transnational insecurity required an innovative response from government. ADF involvement in disaster relief reflected the trend towards multiagency responses to crises, usually called the “whole-of-government” approach. The role of Australia’s defence forces had also evolved beyond war-fighting to include, for instance, border patrols, resource and fisheries protection and humanitarian assistance after major emergencies. The recent acquisitions of the C-17 Globemaster aircraft and the Canberra class Landing Helicopter Dock vessels were not determined by the needs of humanitarian assistance – but they were justified along those lines, and have undoubtedly increased the ADF’s capacity to undertake such missions.

Since the ADF’s response to the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Australia has continued to use its military forces to provide assistance to the international community after natural disasters, both to countries in the region and further afield. Humanitarian concerns have been given as the prime motivation for responding to such disasters, as they should be for a humane and civilised country. Nonetheless, specific political, economic and strategic conditions have led to policies and circumstances in which Australian military personnel have been asked to contribute to such relief efforts over the past 100 years. Later events have shown that this attitude endures, and that Australia will continue to assist our neighbours in their time of need.