The lack of preparation and leadership in East Timor could have had disastrous consequences.

At its peak, the INTERFET coalition was made up of contributions from 23 countries and numbered close to 11,000 military personnel, led by an Australian commander, Major General Peter Cosgrove, and Australian headquarters. The Australian Defence Force (ADF) provided more than 5,500 troops to this coalition (around 5,000 from the Australian Army, more than 270 from the Royal Australian Navy and close to 420 from the Royal Australian Air Force). This was the largest deployment of ADF personnel since the Second World War, and perhaps the most complex strategic challenge Australia had faced since the 1940s.

The INTERFET mission was remarkably successful. The UN had given INTERFET three missions - to restore peace and security in East Timor, to protect and support UNAMET mission, and to facilitate humanitarian assistance operations. All of this INTERFET accomplished - at the lowest possible cost in Australian lives and within only 157 days. Policymakers and decision-makers in Canberra and New York certainly had not anticipated such success with so little cost, within such a timeframe. So what can be learned from the command, control and planning process that accompanied INTERFET?

Private Tammy Smithson provides medical assistance to a child in Suai's marketplace during Operation Laverack, 29 October 1999. Photograph: Gary Ramage. V9917407 Image courtesy Department of Defence.

The ADF in the late 1990s was very much an organisation structured for peace, in both physical and mental terms. When the East Timor crisis struck, it found itself hollow and profoundly unsuited to a large-scale overseas operation like that demanded by INTERFET. The Army in particular had atrophied since the Vietnam War. It did not simply lack experience in expeditionary operations of this scale; it had been actively structuring itself in a manner that would impede its ability to conduct such operations after a string of ‘efficiency’ initiatives. The Defence Efficiency Review alone gutted numbers and capabilities tied to a potential need to fight abroad.

Within the Army there was a belief verging on gospel that no unit outside 3 Brigade, the Army’s high-readiness formation, would deploy into a warlike situation. In 3 Brigade itself, thinking was aligned to the deployment of the ‘online’ battalion group at most. The idea of a large Australian force as the core of a coalition under ADF leadership was seen as beyond sensible consideration. The focus of ADF training naturally flowed from these views of the strategic landscape. The ADF had never practised mounting an overseas operation on such a scale – only what it would do once in theatre. It therefore failed to develop or test enabling functions, nor had it tested newer ‘joint’ organisations and capabilities.

On the eve of the INTERFET deployment, however, the CDF, Admiral Chris Barrie, reassured the Australian public that the ADF had a comprehensive planning process already in place. The Minister for Defence, John Moore, assured the world that prudent preparations had been going on throughout 1999. Both statements were, of course, true – from a certain point of view. But the experience of planning for INTERFET was deeply problematic, and the plan bore all of the scars of an ADF, and a wider defence organisation, conditioned for peace at best and limited operations at home at worst.

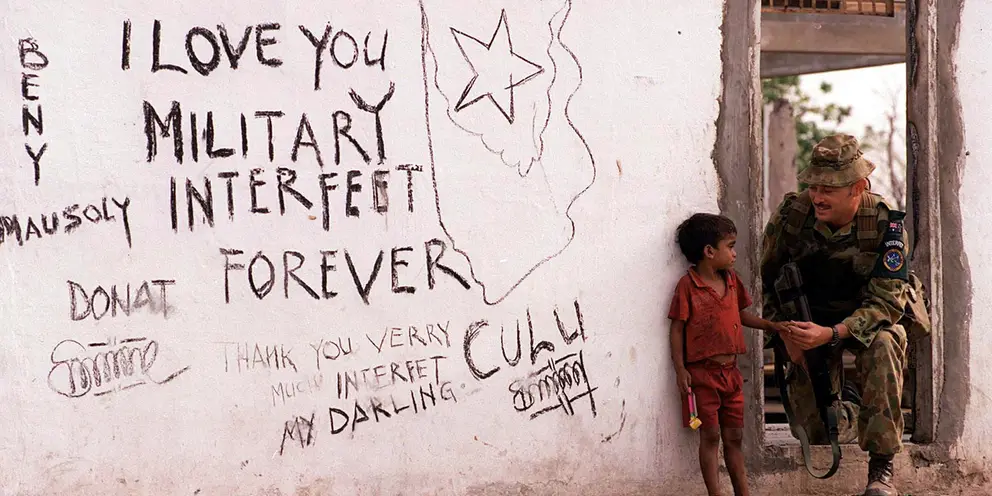

Corporal Andrew Barham stops to talk with a child who has returned to the devastated town of Suai. 29 October 1999. Photograph: Gary Ramage. V9917535. Image courtesy Department of Defence.

Planning problems

ADF expeditionary planning problems began at the very top. Strategic guidance was lacking. There was no new Military-Strategic Estimate, for example, produced after March 1999 despite the looming crisis in East Timor. In government there was a clear feeling, and some angst at the strategic level within Defence, that interdepartmental activities had been dominated by DFAT and PM&C. They pushed their own agendas - primarily the importance of maintaining the relationship with Indonesia. There seemed a belief that readying forces for deployment (an obvious requirement for any significant military operation) would negatively impact attempts to resolve the Timor crisis peacefully. It seemed to some observers that the best thing Defence could do was to sit at the back of the room and keep quiet. With Prime Minister John Howard personally involved in the East Timor crisis, ‘the long peace’ had also left the national security apparatus profoundly unpractised. It had to be slowly led by Defence through a range of key decision-making moments throughout the crisis.

Prime Minister John Howard visits troops in East Timor in late November 1999. V9925424. Photograph: Corporal Troy Rogers. Image courtesy Department of Defence.

There were also significant frictions between senior uniforms and Defence public servants, for example. From the start, the central strategic focus seemed to be on how to get out of East Timor and transition to a UN operation as fast as possible, rather than what might be needed to be done to complete the mission. Defence cobbled together ad hoc structures to deal with the complexity of mounting a large politically sensitive operation outside Australia, reflecting the lack of a standing capacity to deal with this type of crisis. Significant gaps in strategic thought emerged. Beyond a desire to deploy a Media Support Unit (MSU) to East Timor, for example, no Defence public affairs plan was ever drafted for INTERFET prior to its dispatch, nor was any domestic or international public information strategy covering the military operation ever considered at the strategic level, until Indonesian information operations and their strategic impact led to a scrambled response in early October 1999.

More significantly, more concrete problems connected to the high-level ADF command and control apparatus soon emerged. The complex and problematic command and control relationships that had grown during the ADF evacuation operations from East Timor (Operation Spitfire) were inherited by INTERFET. Major General Cosgrove, as Commander of Spitfire, had been placed in command of the umbrella organisation for all ADF evacuation operations in East Timor. Yet for the concurrent Spitfire Special Recovery Operation (SRO), the Commanding Officer of the SASR, Lieutenant Colonel Tim McOwan, not Cosgrove, was designated the ‘Evacuation Commander’– and he reported to Headquarters Special Operations (HQSO) for this contingency, not DJFHQ. Moreover, in practical terms Cosgrove and his headquarters did not exercise command so much as monitor its activities. Over the top of such arrangements, due to the ‘political nature’ of any operation mounted, the CDF sought communication, and control if necessary, through Major General Mike Keating’s Strategic Command Division (SCD) in Canberra.

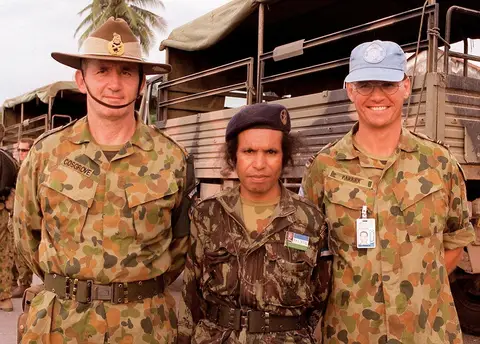

Major General Peter Cosgrove, Commander Interfet, with Falintil Vice Commander Taur Matan Ruak and Lieutenant Commander Ian Parker, RAN, an observer with UNTAET. Photograph: Sergeant W. Guthrie. V9923508 Image courtesy Department of Defence.

As Spitfire wound up on 18 September, Admiral Barrie appointed Major General Cosgrove as Commander INTERFET. Problems associated with what happens when peacetime structures meet the political and strategic reality of a large, important military deployment began to be exposed. INTERFET was a big deal. It was the centre of attention from the Prime Minister downwards. Thus Cosgrove was placed under Barrie’s direct command, and was to report through the CDF to the Australian government and the UN. This meant that Cosgrove spoke daily with Keating. Thus SCD transformed over the course of INTERFET into a pseudo-operational headquarters, with Keating drafting Barrie’s paperwork for Cosgrove, and Cosgrove ringing Keating to seek counsel as to how he should reply.

While it was entirely within the CDF’s remit to make such command arrangements, this was not how the ADF had planned or structured itself for operations. Rather, based largely on the experiences of running large-scale tri-service exercises in the early 1990s, the then CDF, General John Baker, had raised Headquarters Australian Theatre (HQAST) and appointed a permanent ‘theatre commander" in Sydney in 1996 to create a separate, operational-level headquarters to command, plan and conduct joint operations. The deliberate bypassing of HQAST in favour of the Cosgrove–Keating–Barrie axis left a tangled thicket of command relationships behind.

This reflected a political reality: INTERFET was enormously important to the government domestically, and to Australia’s standing in the region and the world. Even comparatively minor tactical operations and incidents had potential strategic and political consequences. The Prime Minister and Cabinet demanded timely and direct answers from Baker with an expectation he had direct knowledge of events on the ground. Putting Cosgrove under his command helped ensure this would happen and shielded him from the multitude of other players who may have wanted to exercise their influence. But this decision demonstrated a lack of confidence in the theatre model that permeated the upper echelons of the ADF.

While the ADF had a basic idea of how the theatre model was supposed to function, the specifics were still being fleshed out. Faced with urgent deadlines, senior officers focused on making things work, rather than respecting technical, untested command and control pathways. Personal relationships and service loyalties trumped doctrinal notions of theatre command. Confusion was the predictable result of high-level command and control arrangements, where established pathways and chains were to some extent circumvented or ignored. Certainly what was confusing within the ADF was even more so to external coalition partners.

Aboard Tobruk

An example of the consequences of high level command and control muddles involved a series of events at Headquarters 1 Brigade in Darwin. Brigade headquarters ordered the squadron to load its vehicles aboard Tobruk on 8 September. The task was completed in the early evening after a quick farewell ceremony. The subsequent C Squadron vehicle embarkation was a very public event. By Tobruk's direction, C Squadron personnel boarded the following day. Discussions ensued on the bridge of the vessel, between its captain and the Officer Commanding the cavalry squadron, concerning putting to sea that night, or the following. The next day, however, the cavalry major took a call from Headquarters 3 Brigade, demanding to know what was going on and who had authorised his squadron to load. Apparently elements within ADHQ were ropeable with the ‘overt’ loading of armoured vehicles at a particularly vulnerable point in diplomatic activity with Indonesia, and had vented that frustration upon Headquarters 3 Brigade. The media messaging of ‘troops prepare for war’ was not considered helpful at this point. It was made crystal clear to the OC that under no circumstances was he to sail without instructions from Townsville. C Squadron personnel duly disembarked, leaving their vehicles and a small maintenance team aboard Tobruk. Over the next few days the captain of Tobruk, with what appeared to be unambiguous direction from his naval chain of command, contacted the squadron a number of times, ordering them aboard, as Tobruk intended to sail. The OC, in accordance with the instructions he had received from 3 Brigade, declined. Eventually the squadron re-embarked on 16 September, minus its OC who still refused to board for fear of the ship sailing during the night. At last, with permission from 3 Brigade, he finally boarded the next day.

Soldiers from 3RAR conduct a cordon and search operation in Dili 24 September 1999. Photograph: Corporal Darren Hilder. V99305 Image courtesy Department of Defence.

This debacle of C Squadron’s on-again, off-again antics with Tobruk was remarkable on a number of levels. The cavalry squadron assumed that 1 Brigade headquarters was ‘in the know’. This was not the case. Rather, the brigade commander was responding to naval requests which had come directly from the CDF’s office, unbeknownst to him, as a deception operation aimed at the Australian media. The effort was successful. Deception was certainly achieved, and not just of the media. Headquarters 1 Brigade might reasonably have assumed the order to place C Squadron aboard Tobruk had been synchronised with all elements at ADHQ, DJFHQ and 3 Brigade. This too, was not the case. All actors were doing what they thought ought to be done but without the necessary information to guide them.

A useful case study of the lack of real ‘tri-service-ness’ within the ADF was Major General Cosgrove’s own headquarters. In August and September 1999 DJFHQ was essentially an army headquarters, while labelled ‘joint’, and fitted for (but not adequately with) the other two services. It was absolutely land-centric; its maritime and air components were not permanently manned, other than a single naval and air force liaison officer. When air and sea staffs eventually arrived, they quickly realised that the headquarters planning staff had hitherto been meeting essentially without RAN of RAAF representation. Indeed, the Naval Component Commander was forced ask to be included in their briefings. Nor had Cosgrove previously worked with either of his RAAF or RAN component commanders.

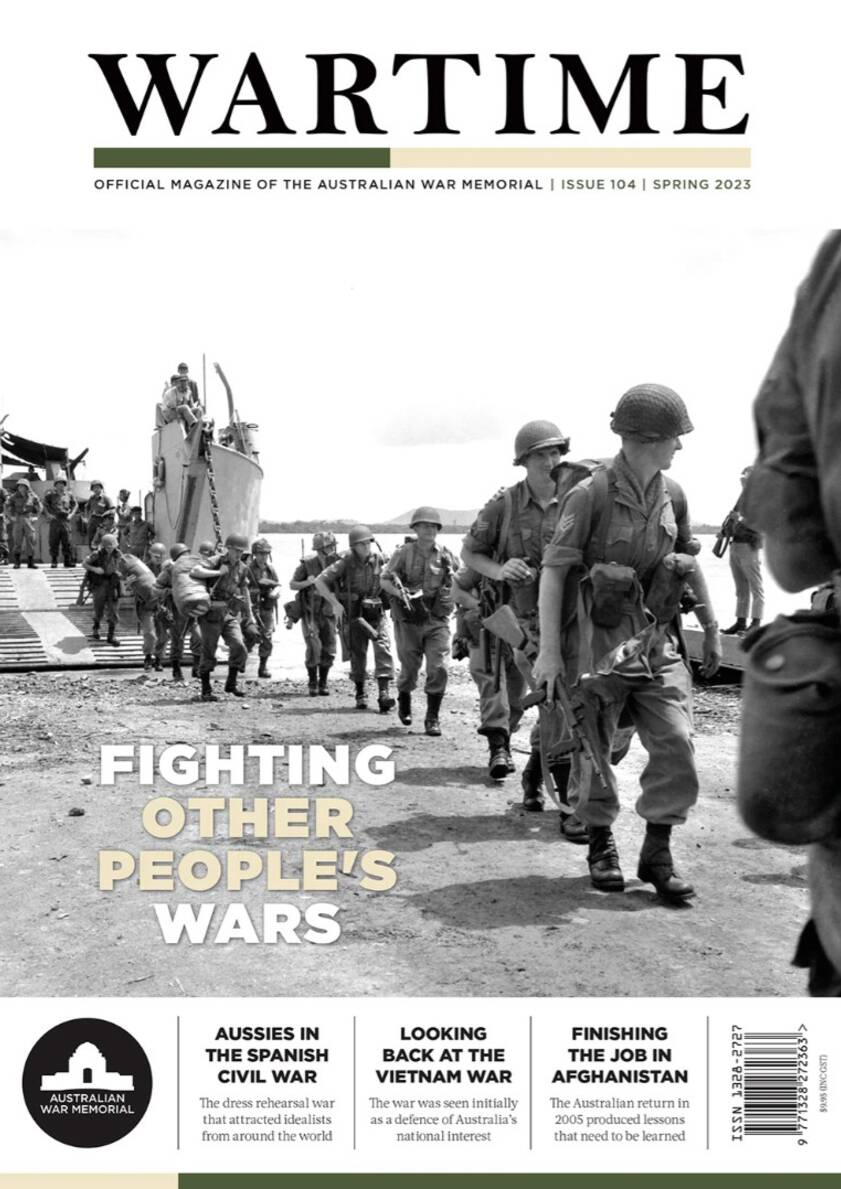

Elements of 5/7RAR disembark from a Navy LGH during the occupation of the Oecussi Enclave, 23 October 1999. V9914430 Image courtesy Department of Defence.

Army planners seemed distinctly unaccustomed to the other two services questioning what they might be doing, and why they were doing it. The root of such problems, however, ought not to be laid solely at the Army’s doorstep. After all, difficulties of tri-service integration were well-known to HQAST beforehand, and little effective action had been taken to address it. So too, a range of RAAF and RAN difficulties in this regard were self-inflicted. The RAAF had chosen, for a variety of reasons, not to fill its billets within DJFHQ on a standing basis, while the naval component of DJFHQ was established in January 1999, but at Maritime Headquarters in Sydney, not with the rest of the headquarters in Brisbane.

Secrecy

Beyond issues of command and control and tri-service cooperation, a third significant driver of planning difficulties was a continuing veil of secrecy drawn across anything to do with East Timor until the last possible moment. DFAT’s insistence on the primacy of the relationship with Indonesia was the justification for such secrecy. Certainly, a level compartmentalisation was standard ADF practice, yet the degree of secrecy in this case, and how late it was enforced, was not. Sensitivity over the bi-lateral relationship and how Indonesian perceptions of overt ADF preparations might impact upon it, were overwhelming issues. The result was a situation where the authority for force preparation, readiness and deployment to mounting bases was removed from appropriate operational commanders. Instead, each was forced to seek endless approvals from the strategic level for any and all changes. The process was time consuming, added little value and significantly increased the workload of staff at multiple headquarters.

Australian troops take up position on the Suai shoreline during Operation Laverack. Photograph: Sergeant W. Guthrie. V9910029 Image courtesy of Department of Defence.

For a number of senior ADF figures it was not so much the early confidentiality and clandestine nature of planning that was problematic, rather the fact that the information was restricted for so long, right up to the moment of the landings themselves. As it became apparent that the potential operation was getting bigger and bigger, planners at DJFHQ and Headquarters 3 Brigade needed to bring in subordinate units, and for some considerable time this was forbidden.

The first casualty was the planning process itself. Ideally the process would have begun at the top and worked its way down. Specialist expertise would be drawn from across the ADF as required, and developing plans would be back-briefed up the chain to ensure the final product was militarily practical, and in alignment with government intent. This did not happen. Rather, crisis and pseudo-panicked planning took the place of broader, more circumspect and deliberate preparations. Information constraints caused almost a reverse sequence where the tactical and operational levels were forced to plan with limited guidance. Even at DJFHQ, the fulcrum of planning efforts once they had begun, staff complained of a lack of clear direction, and of parameters within which to work.

The INTERFET ‘plan’ was, as a result, essentially one designed and written in haste at Headquarters 3 Brigade, the ‘land’ component headquarters. By necessity, this ‘land’ plan was itself shaped by the requirements of the Spitfire evacuation contingency – an entirely different operation. The problematic nature of this ‘reverse’ sequence (especially as it pertained to logistics) was not lost on those doing the planning. Countless frantic phone calls were made, and personal contact between commanders took place amidst an all-consuming blur of activity, but a formal planning framework was consistently lacking. Further, additions and amendments to the initial 3 Brigade concept, as it made its way back up the ADF chain, were undertaken as a sort of disjointed incrementalism which unfolded on the run. This process in itself consumed considerable time and effort and was a marked distraction.

Moreover, the very strict control on the number of people who could be ‘read into’ preparations for deployment acted against one of the primary strengths of the doctrinal Military Appreciation Process, which relied upon the combination and integration of a broad range of subject-matter experts. Much specialist advice was subsequently not available to planning cells at in Townsville and Brisbane. When individuals were cleared to join them, they were often frustrated to see that their early advice would have improved the plan, or saved time by overcoming difficulties already encountered. Under such circumstances it was little surprise that the planning focus in Australia prior to INTERFET deployment was always simply on getting there. INTERFET’s mandate included responsibilities such as humanitarian relief, but these received little more than lip-service in the rush to formulate a plan to arrive, and arrive safely.

East Timor's independence leader Xanana Gusmao arrives at Komoro Airport for the official handover ceremony by Indonesian authorities, 30 October 1999. Photograph: Sergeant W. Guthrie. V9918304. Image courtesy Department of Defence.

In many cases the most obvious and dramatic problems associated with the compartmentalisation of information during the INTERFET planning process manifested at a unit and sub-unit level. Strict secrecy meant no ability to plan ‘vertically’. Units who were unable to prepare beforehand crashed through their notice-to-move thresholds. HQAST took advice from the environmental commanders as to what was a ‘reasonable risk’ in this regard – considerations that meant little at the coalface, especially for logistics units. By the final planning stages the situation in East Timor and Australia’s likely military role were already a media issue. Continuing secrecy, however, still robbed deploying units of valuable preparation time.

After the fact, INTERFET units spoke with one voice in this regard. One of Brigadier Evans’ two infantry battalions, 3RAR, later rued the fact its deployment was well beyond its Capability Preparedness Directive requirements, and urged in future for low readiness units to be manned to sufficient levels of personnel, stores and equipment to allow immediate non-augmented deployment – unlike the situation in September 1999. Crucially, opportunities for training associated with ‘rules of engagement’ were also severely curtailed. The lateness of issue for these rules, 72 hours before the launch of the operation, was a universal concern for tactical commanders.

So what can be said of such difficulties? In East Timor the Army relied entirely too much on skilled, dedicated and adaptable people who made things work in spite of the systems in place – not because of them. Much of this was the legacy of an organisation structured for peace, and of a concept of its possible employment - in line with the strategic guidance provided to it - that failed to take into account the reality of what it would actually be asked to do. No one in a green uniform in the 1990s seriously contemplated the deployment overseas of a divisional-sized force under Australian leadership.

INTERFET worked in spite of such weakness. It worked because no one pushed back. This is unlikely to be consistently the case in all future expeditionary deployments. In 1999 the Army was confident in what it thought it could do, not in what it might be called on to do. There is a difference. The consequences of failing in East Timor in 1999 would have been far-reaching. The consequences of failing the next time the ADF is called upon to launch and perhaps lead a large, expeditionary military operation in the absence of a great power structure within which to comfortably nestle, might be catastrophic.