During the Second World War, Papua New Guineans were a small but crucial part in the fight against the Japanese.

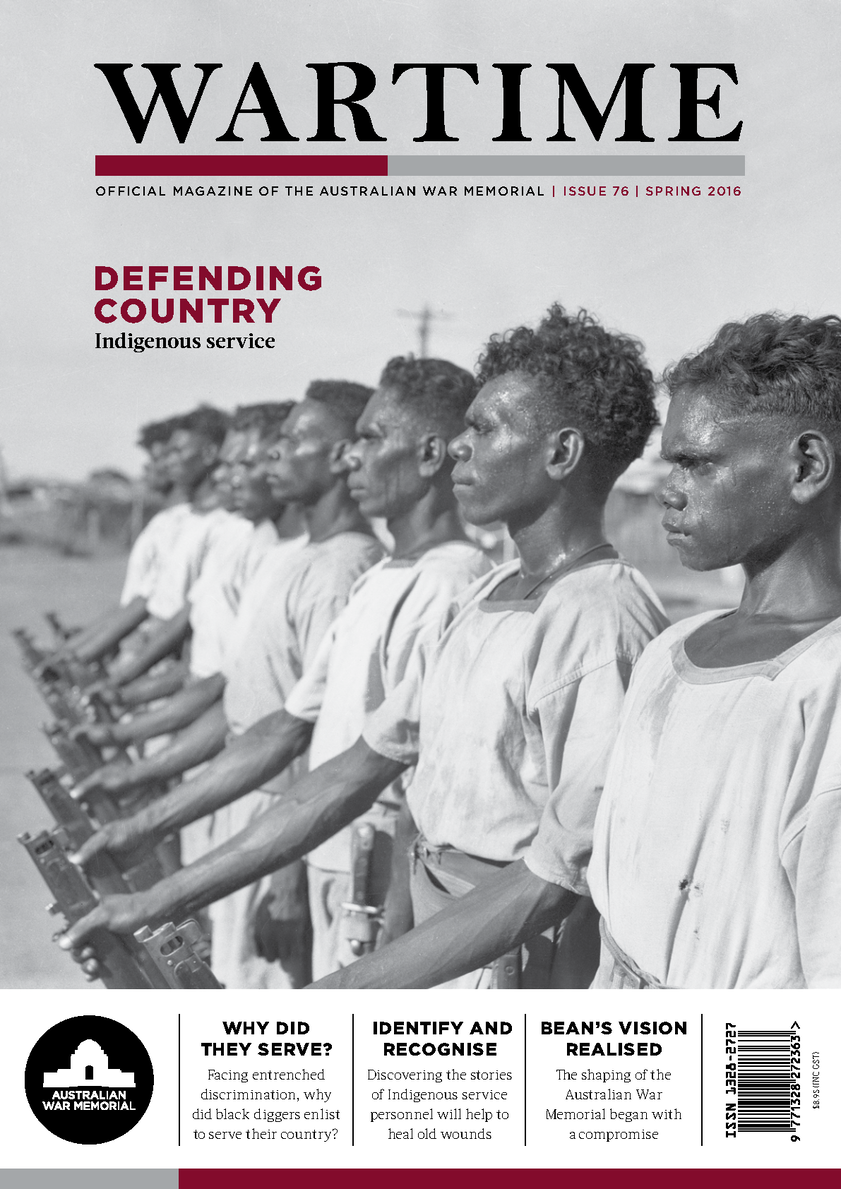

Each year on Papua New Guinea’s Remembrance day, 23 July, people gather at the National War Memorial, close to the bustling Koki markets in Port Moresby, to remember their people’s involvement in the Second World War. They do so around the quintessential symbol of the war in Papua New Guinea (PNG): a bronze recreation of George Silk’s famous photograph of a “fuzzy wuzzy angel”, Raphael Oimbari, guiding an Australian soldier with bandaged eyes, George Whittington.

Papuan native Raphael Oimbari helping Private George Whittington towards a hospital.

This is a particularly Papua New Guinean monument. Whittington is portrayed in bas relief, while Oimbari steps out of that panel to be shown in three dimensions. Similarly, PNG’s national day of remembrance commemorates not the end of the First World War, as in Australia, but the first action of the Papua New Guinean troops on the Kokoda Trail on 23 July 1942. National commemoration of the war therefore focuses equally on the two pillars of Papua New Guinean service in the Second World War: the crucial roles played by carriers and by soldiers in support of Australian colonial rule in PNG.

For those areas of PNG that were fought over or occupied, the Second World War was a period of upheaval. In Japanese-held areas, Australian rule was usurped, and Papua New Guineans subjected to deprivation, bombing and destruction of their homes and gardens. War touched many Papua New Guinean lives profoundly, and shaped the nation for years to come. Sir Michael Somare, for instance, the first prime minister of PNG in 1975, attended a Japanese primary school during the occupation of the Sepik region. Many worked for the Japanese, some willingly, many under duress.

By contrast, for almost a third of the Papua New Guinean population, the war was distant or non-existent. Many, particularly in the highland region, had little inkling that a war was raging along the coast, save for the occasional errant aeroplane.

Life for Papua New Guineans in Australian-held regions was often better than under the Japanese, particularly in the last year of the war as the supply-starved Imperial Japanese Army increasingly raided villages’ food stocks. Australians left local gardens largely intact, while Papua New Guineans in government employ received regular, if monotonous, supplies of food. One of the most famous songs in Papua New Guinea, “Rici mo i anina”, told the story of a Papua New Guinean soldier pining for his usual fare of yams and taro, but faced with yet another meal of white rice.

Papua New Guineans came under the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU), a military organisation that in April 1942 assumed control of the two separate administrations of Papua and New Guinea. This division was a legacy of the different legal frameworks governing the Australian Territory of Papua, and the former German colony of New Guinea, captured in 1914. While ANGAU oversaw health, law and education, its primary function was the support of the army through the provision of intelligence, topographical information and, most importantly, labour. These tasks saw the organisation grow from around 450 Australian personnel in 1942 to over 2,000 by the end of the war.

ANGAU’s control was exercised through the Royal Papuan Constabulary and the New Guinea Police Force, each composed of a Papua New Guinean rank and file who assisted in enforcing the sweeping powers of Australian officials, known as kiaps. The police also played a vital role in the war effort. As they knew the land and the people, and were armed, they acted as guides, scouts and sometimes as soldiers. Many Papua New Guineans also served with the Allied Intelligence Bureau, helping to reconnoitre Japanese strengths and dispositions, as well as to maintain contact with local populations.

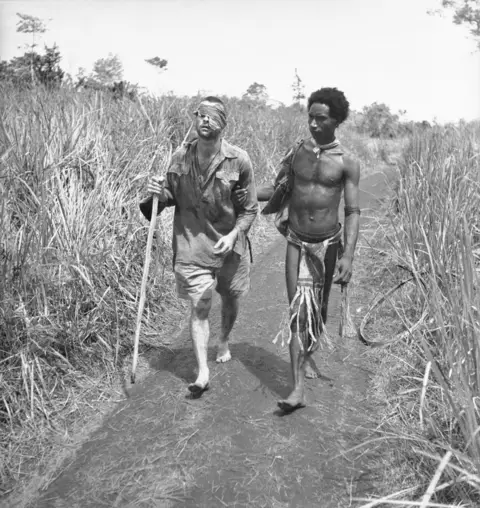

The most significant and well-known Papua New Guinean contribution to the war effort was as unskilled labourers and carriers. They built roads, airfields and hospitals, unloaded cargo, grew vegetables, crewed small ships plying the coast, and tapped rubber. Around 900 Papua New Guineans were medical orderlies, while others worked as laundrymen and servants. For Australian soldiers, the most readily recognised role played by Papua New Guineans was their work transporting supplies to the front lines, and returning the wounded to hospitals in rear areas.

Native bearers carrying a stretcher case down from Shaggy Ridge, above the Ramu Valley, 1944.

Carriers were initially volunteers, but when the numbers coming forward proved inadequate, ANGAU turned to compulsion. ANGAU officials were empowered to conscript up to one third of the able-bodied men of any village, although in many instances this proportion was far higher. As the war progressed, some regions were particularly stripped of young men, and some ANGAU officers resorted to threats when faced with Papua New Guinean reluctance. At any one time during the war, there were between 25,000 and 37,000 Papua New Guinean labourers, and an estimated total of 50,000 served. Of these, at least 2,000 died.

Carriers are best remembered for their role in returning wounded men from the front line. The only way to get the wounded out of the steep terrain was to carry them, and it took a team of between and eight and 16 men to transport each Australian. The carriage of wounded men to field hospitals, or to points from which they could be carried by road or air, was a key part of the medical system.

Papua New Guineans did their best to ensure that their wounded charges suffered as little as possible, and their efforts were almost universally appreciated. Sapper Bert Beros, in his well-known poem “The Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels”, wrote of these men that “the look upon their faces makes us think that Christ was black”. Although Beros’s words were intended as a tribute to the efforts of carriers, the poem’s fame has overshadowed the wide range of experiences and motivations of Papua New Guineans. Their often ambivalent attitude towards the Australians who had forced them to work in harsh conditions, away from their families, has been overshadowed by the image of the loyal “fuzzy wuzzy”.

Papuan Infantry man, 1941.

While carriers were central to the war effort, Australians were reluctant to recruit Papua New Guineans as soldiers. Colonial authorities worried about the threat that armed and well-trained Papua New Guineans might pose to Australia’s rule, and some army officers raised questions about the suitability of “the native” to modern soldiering. Even in 1940, the possibility of raising a unit of Papua New Guineans was still being debated in Port Moresby and Canberra. In the end, it was the pressing need to free policemen from guard duties around Port Moresby that decided the issue, and the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) was approved in May 1940, although it was not until early 1942 that it received enough recruits to form a complete battalion.

In addition to guard duties, the PIB was conceived as a reconnaissance and raiding force, building on the role already undertaken by the police and Coastwatchers, but in larger and more powerful groups and without the added burden of policing. It was in this reconnaissance role that Papua New Guinean soldiers first met the Japanese, as the PIB scouted the region between the airstrip at Kokoda and the Japanese landings in the Buna–Gona area on 21 July 1942.

Two days later, 35 men from the PIB, led by Lieutenant J. Chalk and two other Australians, set up an ambush near Awala to wait for the approaching Japanese. The trap was sprung on the Japanese advance party, who were riding bicycles and motorbikes, marking the first Papua New Guinean shot fired in anger during wartime. However, faced with overwhelming Japanese firepower, the rifle-armed Papua New Guineans were quickly forced to retreat, scattering into the jungle.

Linking up with the 39th Battalion, the PIB fought a series of delaying actions and mounted reconnaissance patrols while falling back to Kokoda. The battalion fought alongside Australian troops over the entire seven-month Kokoda campaign, eventually losing 15 men killed and over 30 wounded.

New Guinea Infantry Battalion troops on their way to attack the village of Gisananbu, a Japanese position, July 1945.

Despite calls for the unit’s disbandment after accusations of poor performance in its initial clashes with the Japanese, the PIB was retained. After the Kokoda campaign, detachments of the PIB served in the beachhead battles at Buna–Gona, and later in the battles around Wau. In the Salamua campaign of 1943, PIB troops assisted US and Australian units in their fighting along the tracks and ridges to shift elements of the Japanese 51st Division, and later patrolled to the north of the US paratroop landings at Nadzab during the campaign to capture Lae.

In this way, Papua New Guinean troops were often at the forefront of Australian campaigns, usually performing an intelligence rather than a fighting role. Papua New Guinean troops were expected to range in front of the Australian army, observing the enemy unseen and liaising with local civilians. This was a crucial role in a largely infantry-based war without continuous front lines, fought in jungle terrain that restricted observation from the air. In this environment the PIB earned the sobriquet “green shadows” for their ability to move through the jungle undetected to report on the enemy.

The use of a company of the PIB in the capture of Kaiapit by the 2/6th Independent Company in September 1943 is a fine example of the use of Papua New Guinean troops. In this operation, the 2/6th were daringly flown 40 miles (65 kilometres) from Australian positions into enemy territory. They landed on a rough airstrip, and then formed up for a lightning attack on the Japanese base and airfield at Kaiapit in the Markham Valley north-west of Lae. Despite Japanese counter-attacks, the operation was successful and greatly speeded up the Australian advance from Lae.

However, the landing of the 2/6th in one lift by unarmed Dakota transports was only made possible by the presence of the PIB in the area beforehand, which confirmed the absence of Japanese soldiers from the landing strip. Seeing Papua New Guinean soldiers from the plane as he flew in, Lieutenant Gordon King recalled being reassured by the presence of the PIB. Nonetheless, the PIB was not considered to be a front-line unit, and when the time came to assault Kaiapit, Papua New Guinean troops were instead deployed to screen Australian positions and guard the carrier lines.

The PIB’s utility as scouts and in conducting raids on the Japanese was such that army authorities approved the raising of three New Guinea Infantry Battalions (NGIB) in 1943. By the war’s end, two more battalions were forming, with all six grouped under the aegis of the Pacific Islands Regiment (PIR) in early 1945. Only the first two NGIB battalions saw action alongside the PIB in the Australian campaigns to liberate their territory on New Britain, Bougainville, and in the advance from Aitape to Wewak.

No. 5 Platoon, A Company, 1st Papuan Infantry Battalion, escorted by Sergeant R.H. Barker, on patrol. New Guinea, July 1944.

In all, around 3,500 Papua New Guineans served in the battalions of the PIR, which fought in every Australian campaign in PNG apart from the defence of Milne Bay. Papua New Guinean troops fought hard throughout the war, and ended their service with one of the highest kill-ratios against the Japanese in the Allied forces, while at least 51 Papua New Guinean soldiers died during the conflict. As British subjects, these men are recorded on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial alongside other Australian soldiers.

Despite having a strong reputation as fighting troops, Papua New Guineans also attracted the disapproval of the army and the colonial government because of a number of discipline issues, particularly in the final year of the war. In one case, troops shot at New Guinean policemen after a fellow soldier was arrested in Annaberg, New Guinea.

Senior Sister E.B.Y. Cameron with members of the Papuan Infantry Battalion at the 106th Casualty Clearing Station. Heldsbach Plantation, New Guinea, 1944.

While colonial authorities played down cases of poor discipline away from the front lines, they were far more concerned about instances of disobedience, such as in Lae in 1945. Here, troops embarked on a campaign of disobedience over an ill-conceived army plan to replace the Australian uniform with “native” dress: a laplap, or loincloth, and no shirt. This was a grave insult to a regiment that had shared the burden of fighting alongside white troops, and was a reminder of the unequal place accorded Papua New Guineans under Australian rule. While this issue was resolved by an army about-face on the matter, the PIR suffered in reputation.

After the war, units of the PIR were used to guard Japanese prisoners of war and Japanese war criminals on trial on Manus Island. In the two years following the end of the conflict, the regiment’s battalions were slowly disbanded alongside the wholesale demobilisation of the Australian Army, until the last company was discharged in 1947.

The fear of “arming the natives” also formed an important part of the decision to disband the regiment, particularly as discipline issues cemented the view of the PIR as a liability to colonial rule. Moreover, being second-class citizens in PNG, neither Papua New Guinean soldiers nor carriers received pensions for their service after 1945, unlike white troops – a fact that continued to rankle until the Australian and Papua New Guinean governments provided a one-off gratuity in the 1980s.

Papua New Guinean soldiers continued to serve during the post-war period. In 1951, the threat of the Cold War was such that the PIR was re-raised to defend PNG, which remained an Australian Territory. Initially a single battalion, the regiment was expanded into two battalions in 1965 in response to fears that Indonesia would launch incursions across the border, as they were then doing in Borneo as part of their policy of Confrontation. Mounting long and arduous patrols across the mountainous border region, the PIR was an essential part of Australia’s defence during the Cold War until Papua New Guinean independence in 1975. Today the regiment, renamed the Royal Pacific Islands Regiment, continues to serve as the core of the Papua New Guinea Defence Force, and maintains a proud tradition of service with Australians.