The Japanese medical system in Papua in 1942-43 created immense suffering for staff and soldiers alike.

The surgeon gazed wearily over the small hut, the thin beams of sunlight through the cracked roof illuminating his cot as he took a brief respite from his work. His tunic was stained red from the numerous operations he had performed in the adjacent makeshift theatre. Nearby, row upon row of barely alive patients lay on scattered leaves and saplings in ramshackle wards, which resembled a pigsty more than a field hospital in the jungle. From the rotting banana leaves that formed the roof, black liquid dripped steadily into the faces of the patients. A passerby would have been unsure if these men were grimly hanging on to life, or just waiting for death.

Medical Lieutenant Bando Jobu must have wondered how it had come to this. Just months before, he had been working at a small hospital in Kagawa, in northern Shikoku, when he received notice that he had been drafted into the Japanese army as a surgeon. After transferring through Mindanao in the Philippines, he had arrived in Rabaul in the mysterious South Seas. Before he’d had time to settle, he was deployed with Commander Horii’s troops to Papua, where he found himself in charge of the 1st Field Hospital behind the main strength of the South Seas Force, which was pursuing Australian troops south towards Port Moresby. The hospital was equipped to hold 150 patients, but at present there were about 800. Further, the conditions in the mountains and the length of the campaign had left them short of staff, almost out of food and without many of the medicines required for basic treatments. Rows of white sapling grave markers over freshly dug mounds were a daily reminder to Bando and his staff of the end result of these shortcomings.

Open barges were used to transport casualties up the Papuan coast towards Lae. Many, such as these wrecks on Sanananda beach, were destroyed by Allied aircraft. AWM 079651

The 1st Field Hospital in Kokoda was part of the medical system established to support the Japanese campaign against Port Moresby over the Owen Stanley Range. A series of field hospitals were established behind the line of infantry troops during the advance. Casualty clearing units moved wounded and sick troops back to the field hospital, or to battalion aid stations, after they were stabilised at the front line by members of their unit with first-aid training. Seriously wounded troops were evacuated to a line-of-communication hospital at Giruwa, on the north coast of Papua, where they would receive further treatment before evacuation to Rabaul or Japan. Less serious patients, particularly those suffering from recurrent malarial fevers or bouts of dysentery, were carried forward behind the infantry line. This would enable them to quickly rejoin their unit once their condition improved; this procedure also reflected hopes that food and medical supplies could be secured once Australian resistance was broken and the prize of Port Moresby taken.

About the same time in Kagi, situated roughly mid-way between Kokoda and the southernmost point of the Japanese advance at loribaiwa, another doctor was experiencing his own hardships. Unlike Bando, who was a civilian doctor conscripted into the army, Yanagisawa Genichird - known during the war period as Yanagisawa Hiroshi - had graduated in 1940 from medical school in Sendai, in northern Japan, and joined the 15th Independent Engineer Regiment as an army surgeon. Yanagisawa had served in Malaya, where he experienced the elation of victory in Singapore, and shared in the honour of a unit citation received from General Yamashita Tomoyuki, the commander of the campaign.

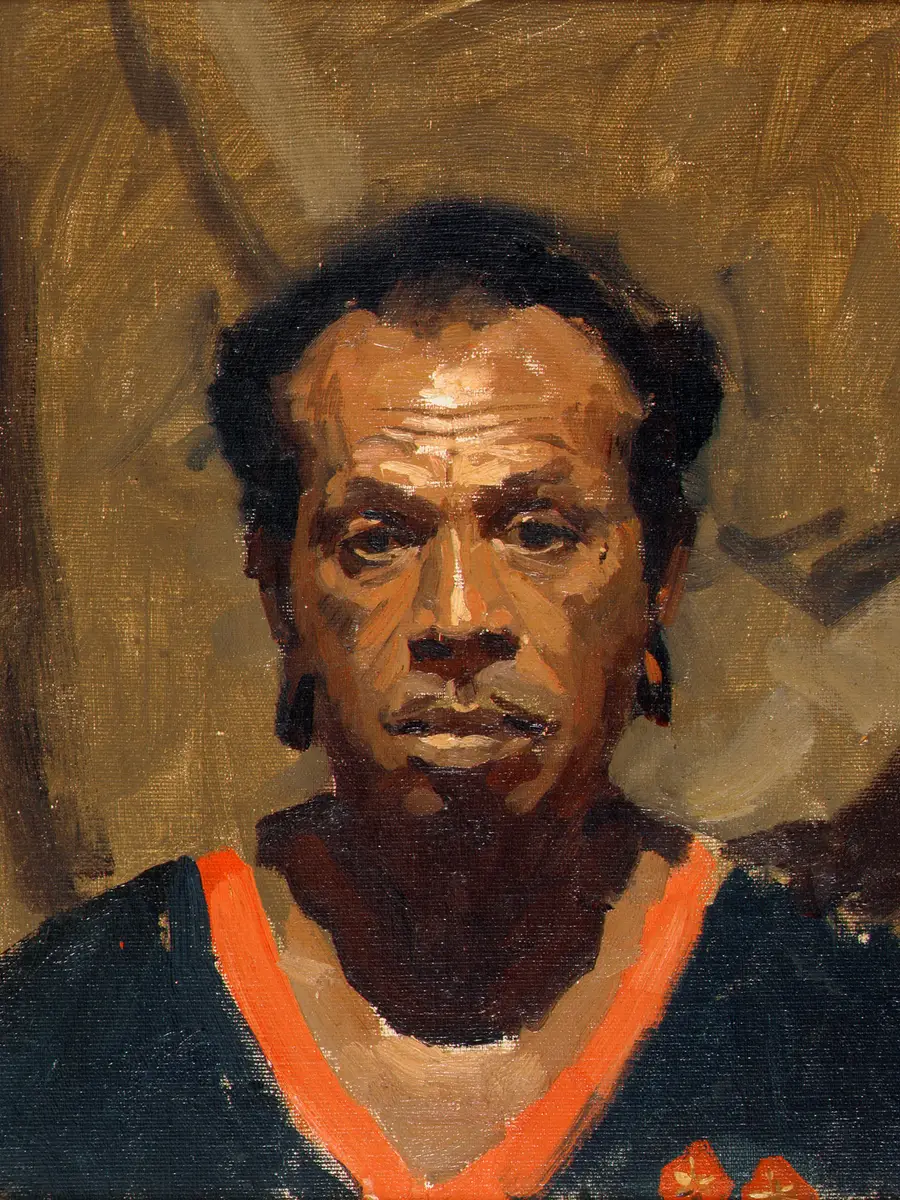

Japanese medical officers in Papua were short of staff, short of supplies and short of medicine.

The 15th Independent Engineer Regiment was redeployed and then sent to Papua as the core of the Advance Party to reconnoitre and repair the roads through the mountains. Yanagisawa had travelled with the unit during the advance, and in mid-September was charged with establishing a “reserve unit” for members of the South Seas Force. Under his care were about 250 sick and exhausted troops, who for several weeks remained alive with minimal medicines; the supplies that were carried from the coast several weeks before had long run out.

The unit was in reality little more than an infirmary. With many suffering malaria, amoebic dysentery and malnutrition, Yanagisawa was struggling to keep them alive, let alone nurture them to health so they could return to the front. Conditions briefly improved when for several days Allied bombers dropped supplies near their camouflaged position. Presumably intended for Australian troops returning to their units after having been scattered during the withdrawal, the supplies of tinned beef, cheese, biscuits and powdered milk provided a nutritious filler for the ailing Japanese soldier.

Poor logistics, stubborn resistance from he Australian forces, the failure to secure Milne Bay and the growing realisation of the importance of Guadalcanal were all factors that led the Japanese generals in Rabaul to decide to withdraw the South Seas Force at the end of September. Caught up in the desperate withdrawal, medical units, which were positioned along the Trail, were forced to move casualties and facilities back to the north coast. Much of the portage was undertaken by labourers from Korean and Formosan [present-day Taiwanese] volunteer units. Patients were often tied with vines to makeshift stretchers, and then carried for days over steep and difficult terrain. Medicos during the retreat provided what treatment they could, but often had to operate without anaesthetic or other drugs. Many soldiers died in terrible pain and suffering.

Medicos during the retreat often had to operate without anaesthetic or other drugs

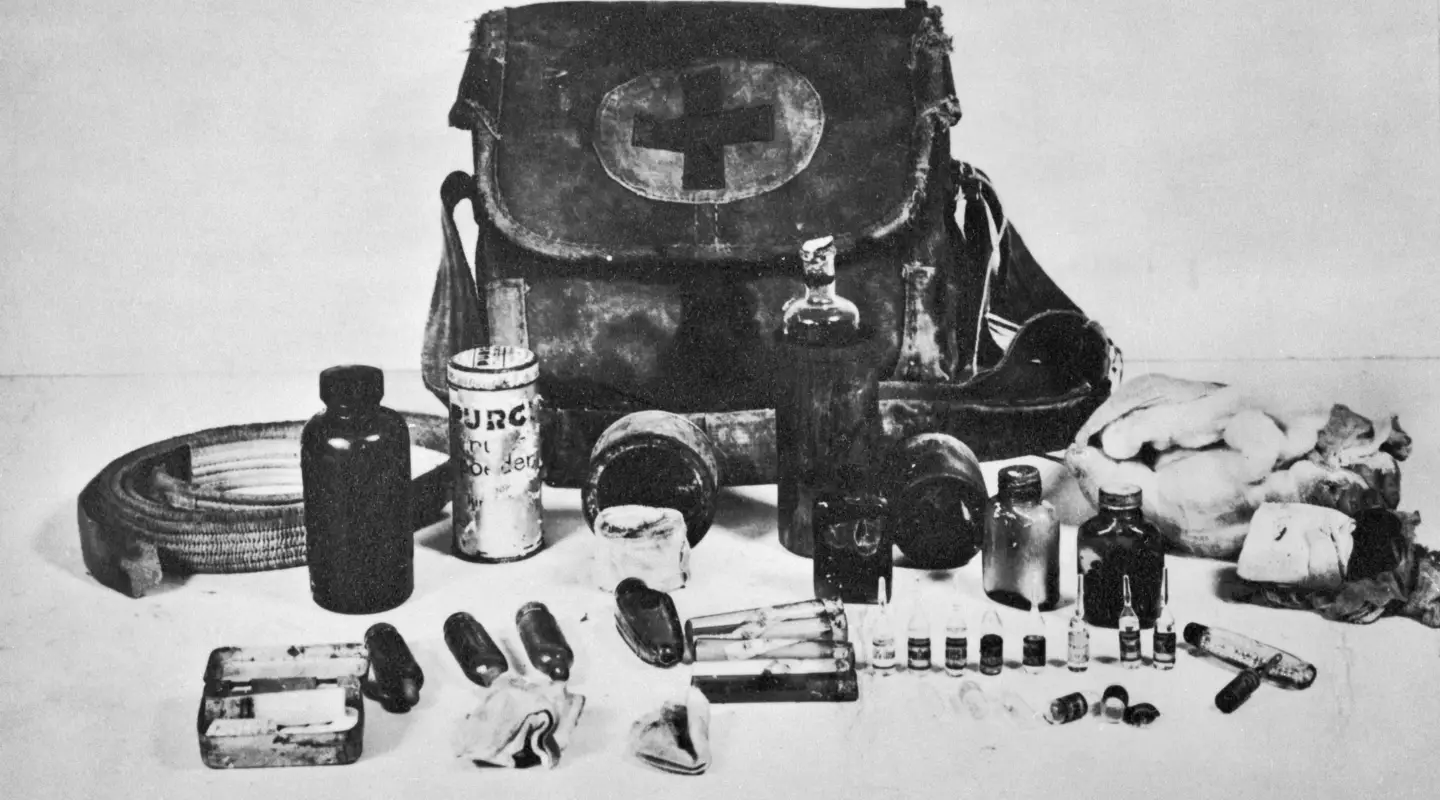

Japanese doctors were often well equipped with surgical instruments in the field, but the circumstances of the campaign in Papua often left them short of medical supplies and staff.

The 67th Line-of-Communication Hospital in Giruwa was overcrowded and, like much of the Japanese force in Papua, suffering from infrequent resupply. In addition, fewer evacuation ships than expected arrived from Rabaul, owing to the Allies’ growing control of the skies over the region. With Australian and American units closing in on the beachhead positions, and with the huge influx of new casualties from the mountains, the commander of the hospital, Lieutenant Okubo Fukunobu, faced a near-impossible situation in attempting to provide for those under his care. In mid-November, Okubo had fewer than 60 staff to care for more than 2,100 patients, most of whom were housed in primitive conditions.

Bandō and the other medical staff deployed in Papua in 1942-43 were not fighting men, but the Japanese military ethos dictated that they would fight and die along with the troops.

When the crunch came, even bed-ridden patients were expected to take up arms, even if these were nothing more than sharpened sticks. Roughly two-thirds of all Japanese forces deployed in the campaign died. The medical staff were not exempt: in Bando’s 1st Field Hospital, only 55 staff from a total 170 survived.