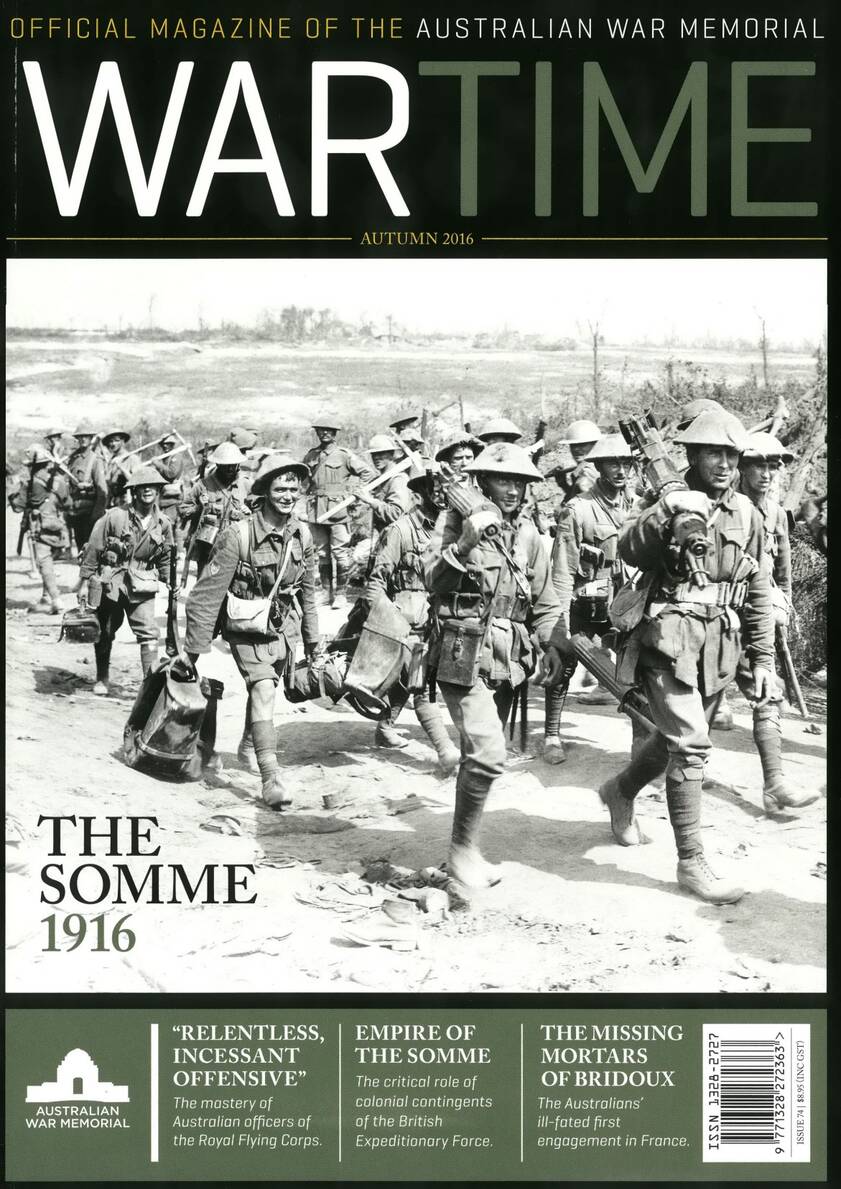

British intelligence systems played an influential role in the conduct of the fighting in 1916.

At the end of 1915 there was a reshuffle of the British high command. In London, William Robertson became Chief of the Imperial General Staff, while at General Headquarters (GHQ ) in France, Douglas Haig took over as commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). Both used the opportunity to reshape the provision of intelligence: Robertson brought George Macdonogh back from France to be the Director of Military Intelligence (DMI), while Haig soon transferred John Charteris, his former intelligence officer at First Army, to become Brigadier-General (Intelligence) (BGI) at GHQ. Both Macdonogh and Charteris would make changes in the organisation and staffing of their departments, marking 1916 as a watershed year for the gathering and analysis of British intelligence.

Strategically, there was less scope for change. Haig inherited a commitment to collaborate with the French in a joint attack against the Germans. Although from February the French would also become progressively sucked into the fighting at Verdun, this general allied intention would become the Anglo-French summer offensive astride the River Somme. This battle would become an increasingly attritional struggle against the German army, in which intelligence played an important role in shaping how Haig understood the situation. Although it was not the only influence upon his perceptions, intelligence did help to sustain a belief that he was winning this brutal fight and, at key moments, it appears to have influenced specific operational choices.

General Douglas Haig (centre) with his French allies, General Joseph Joffre (left) and General Ferdinand Foch.

Collecting intelligence

Front-line sources were the cornerstone of the intelligence system directed against the German army. At the most basic level, the British used binoculars and telescopes to observe their enemy’s comings and goings. In 1916 these observation systems were not particularly sophisticated, and much of the work was delegated to units rotating through the front rather than to specially trained observers.

Since 1914, German artillery had been monitored by flash-spotters who triangulated gun positions by watching for their fire; in early 1916 this system had been standardised across the BEF front. Complementing this work were sound-rangers who located German guns through the noise of their firing (see Wartime Issue 51). This system took a significant step forward in 1916 with the introduction of a new microphone that allowed better filtering of background noise. All these methods of collecting intelligence were passive and relied on the Germans revealing themselves through their activity, but as the war went on, the Germans became adept at camouflaging themselves from both observation and flash-spotting.

More proactively, the British captured enemy soldiers, either in trench raids or during larger attacks. Some Germans would also oblige the British by deserting, but their numbers were always low. To obtain and then exploit the information that could be gathered from these soldiers, the BEF had developed simple interrogation systems. Before 1916 the number of captives was fairly low, so it was possible to subject a large proportion of them to questioning by German-speaking intelligence officers. However, during the battle of the Somme the number of Germans to be interrogated increased dramatically during attacks, and the system was overwhelmed. Collecting stations known as “cages” were established close behind the front. Here hundreds of German soldiers could be searched, questioned briefly by German-speaking non-commissioned officers, and prisoners of particular interest could be passed on to the experienced interrogators. By rummaging through prisoners’ clothing, the British also found large quantities of documents. Some of these, such as marked maps or written orders, were used immediately to inform tactical decisions. Diaries and letters were subjected to closer examination to reveal information about morale or even about conditions on the German home front. Individually, a prisoner or his papers were rarely very revealing, but collectively these snippets could provide useful insight into the German army.

German soldiers in a prisoner “cage”, 1916.

Captured German soldiers being searched early in the Somme campaign.

Adding to the intelligence picture generated by front-line sources were espionage networks behind the German lines. For the British, this ancient technique of intelligence gathering achieved variable success during the First World War. In 1914 the Secret Service’s pre-war preparations were dislocated by the rapid advance of the German army. Complicating the situation, GHQ created its own agent networks in Flanders, and throughout the war the two organisations bickered with one another over how this work should be managed. But by the first half of 1916, things had stabilised, and both the Secret Service and GHQ had multiple networks numbering hundreds of agents across most of Belgium. These spies reported on the presence of German units and observed the railway system, thereby allowing the allies to monitor – albeit with a time-lag of a week or so – the movement of reserves. However, in June 1916 the German counter-espionage authorities managed to break a number of important networks. The timing could not have been worse for the British, as on the eve of their Somme offensive they lost track of some of the enemy’s reserves and their movements.

In 1916 the British also had two further modern intelligence collection capabilities: the interception of German signals, and the use of aerial photography. In the early months of the war, the British had enjoyed some successes with the interception of German wireless messages on the Western Front. But as the trench deadlock developed, the Germans switched to the use of telephones for front-line messages. In early 1916 the British became concerned that their own telephone communications were being intercepted by the enemy – and after the opening of the Somme offensive, their worst fears were confirmed. In response, GHQ hastily improvised an interception capability using electrical earths, loops, and amplifiers. As 1916 went on, in addition to spotting for artillery, the Germans shifted towards greater use of wireless for battlefield communication. The British responded with a network of interception stations. At this point the BEF had little or no cryptographic capability, so the solution of German codes and ciphers seems to have been done in London, where army signals intelligence had been underway for many months, trying to intercept the cable traffic of neutral powers and to track the movements of German Zeppelins.

Aerial photography was also evolving rapidly in 1916. Through 1915 the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had evolved its technology from hand-held cameras to ones mounted on the side of aircraft. In the autumn of 1916 the Type E camera was brought into service; semi-automatic and made of metal rather than wood, it was an important step forward. However, in 1916 it was organisational rather than technical factors that held back aerial intelligence collection. The RFC had developed an ability to collect the raw photos, but there were manifold difficulties in analysing them, and then getting the information – in a timely manner – to those who needed it.

Analysing intelligence

During 1916 the British intelligence system was delivering a steady flow of potentially useful raw information, but this was futile unless it was complemented by a thorough system of intelligence analysis. Unfortunately, at this stage in the war, analysis lagged behind the sophistication of intelligence collection. One important area undergoing a transition was the manning of the intelligence system. When the BEF went to war in August 1914 it took with it a hastily assembled Intelligence Corps composed mainly of civilian linguists who were given commissions and acted as auxiliaries to the “real” intelligence officers of the General Staff. Initially these junior officers were employed mainly in collection, with the business of analysis and assessment remaining firmly within the remit of the regular officers.

But as the BEF expanded, the number of headquarters grew and, almost by default, the Intelligence Corps took on a greater analytical burden, a process hastened by the rotation of staff officers through intelligence roles. The difficulty was that the early cohorts of Intelligence Corps officers lacked military experience, which undermined their credibility. A similar situation existed in London where, in August 1914, all the regular analysts had been sent to intelligence posts at GHQ. They had been backfilled with a variety of civilians-turned-soldiers and ageing officers brought back from retirement. When he returned to the War Office as Director of Military Intelligence, Macdonogh began reforms by bringing in people with specialist expertise. These were often academics with special knowledge of the history, geography or politics of other European countries; they had volunteered for the army in 1914 and were subsequently wounded. However, this change in staffing was gradual and was not completed during 1916.

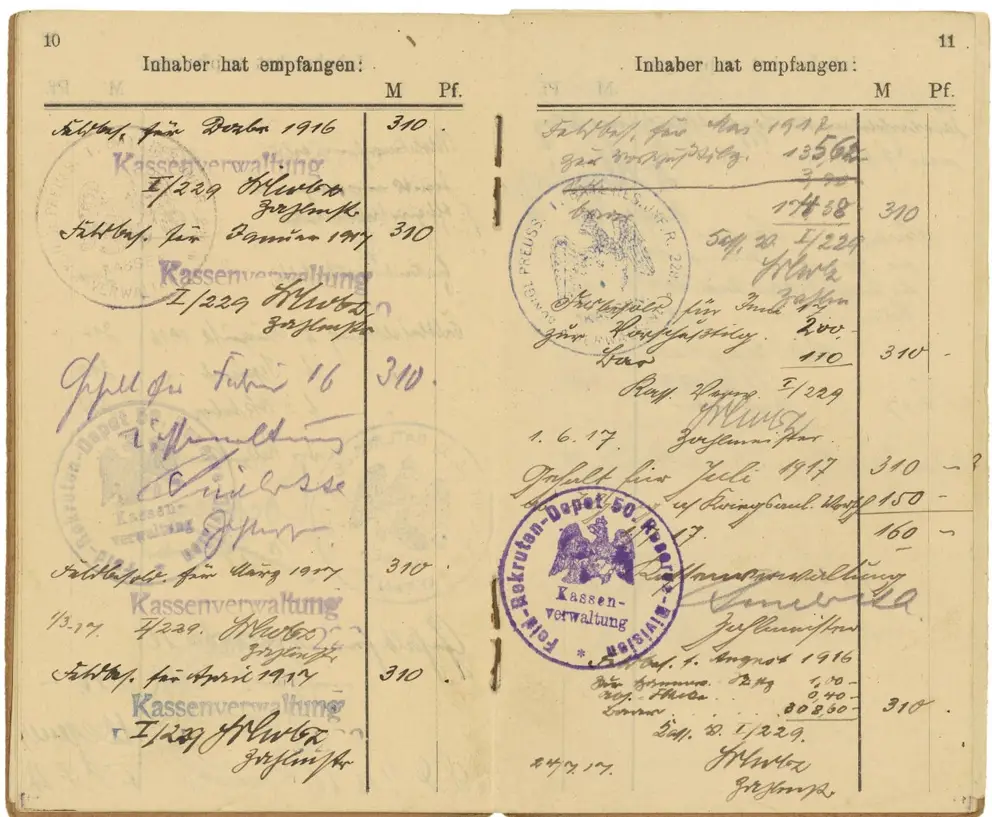

A German soldiers’ paybook.

Analytical techniques were also in transition as the British wrestled with increasing volumes of information and an ever more complicated war. The Secret Service was able to penetrate the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, but they struggled to collect intelligence within Germany. Similarly, Britain’s signals intelligence organisations could read Germany’s diplomatic communications but there were limits to the insight provided. The gap was filled by what would today be called open sources. Both at the War Office and at GHQ, the German newspapers were pored over for scraps of political or strategic information. Most significant in this work were belatedly published German casualty lists. By collating this personnel data, British analysts were able to estimate the overall number of German soldiers killed or wounded. Supplementing this approach, the British and French collaborated in the analysis of prisoners’ pay books. When joining their unit, German soldiers were given a sequential number which allowed the allies to calculate – from the lowest and highest numbers allocated to the men captured – the number of reinforcements the German forces had received, and from this, the number of casualties that had been sustained. From 1916, GHQ began to publish sophisticated reference documents collating all known information about the German army. Also important was the steady flow of intelligence summaries issued on a daily basis by most headquarters. These summaries acted as an “intelligence newspaper” for their readers, but were also formatted in subject paragraphs so they could be cut up and pasted into files. For GHQ, the core analytical focus was maintaining a constant picture of the German forces on the Western Front. Led by the Canadian Corps, who excelled at the graphical presentation of intelligence, this information was increasingly recorded on coloured maps.

The influence of intelligence

During the planning of the Somme offensive, intelligence about Germany’s Western Front reserves was central to British expectations. By the beginning of June they had noted a build-up of German divisions in anticipation of the offensive. The Russians then launched their Brusilov offensive (so named after its commander) and, after a time-lag for the agents to report, by mid-June the British confirmed a flurry of German movement eastwards. It was at this point that GHQ issued the first of their infamous “cavalry breakthrough” plans, which can perhaps be interpreted as a fairly reasonable response to this shifting intelligence picture. By late June the situation was less clear, with the British estimating that the Germans had only three reserve divisions opposite them. However, in reality there were six, and this incorrect information would skew British estimates during the first part of the battle; the error was aggravated by the collapse of many of the networks of agents. On the intended battle front there was a fair amount of wishful thinking in the intelligence assessments. Judgements about the morale of German units were extrapolated from limited and dated information, although on the southern part of the line – where the British enjoyed relative success on 1 July – they correctly noted that German troops were poorer quality and that the area was a lower priority for German engineering efforts.

A British Mark I female tank, 1916. Female tanks were not equipped with the two 6-pound guns found on male tanks. The netting over the crew member is designed to shed grenades.

From his letter home on the eve of battle, we can see that John Charteris believed the fight would be attritional in the first instance, and he even conceded the probability of the struggle continuing into 1917. But the bloody events of 1 July do not appear to have dented the optimism at GHQ. Indeed, within the first two weeks of the offensive they stressed that the Germans were struggling to find reinforcements for the Somme fighting. The successful attack of 14 July bolstered this perception and the subsequent haul of prisoners and documents gave the British a much deeper insight into German morale and casualty rates. This helped to sustain the optimistic belief of both the Brigadier-General (Intelligence) and Director of Military Intelligence that attrition would eventually work in Britain’s favour. By early August, GHQ was assessing that the Somme fighting would drain Germany’s manpower and make the enemy vulnerable to a decisive allied offensive in 1917.

But by early September the intelligence assessments shifted noticeably towards a possible victory in 1916. This change of heart was driven by interpretations of German political developments and a belief that their army’s morale might crack.

London had indicated that the Germans were putting out peace feelers, and the change of German high command from Erich von Falkenhayn to Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff (see Wartime Issue 73) led to a belief that the Eastern Front would be prioritised. Analysis of casualty lists also indicated that earlier fighting had inflicted severe damage upon the German army. On the Somme, various snippets of information were turned into a broader conclusion that German front-line morale had hit a new low. The problem with this extrapolation was that its source was German units already known to have poor morale. Therefore, as the BEF prepared to launch their new tanks against the Germans, they held out the prospect of victory before winter and stressed the need to take advantage of these favourable circumstances. Although the 15 September attack was fairly successful, the Germans held firm and GHQ reverted to a more realistic interpretation of the situation.

And yet, within a couple of weeks, their optimism surged again. In late September the Germans had conducted a full relief of their troops on the Somme front and the new arrivals appeared to have had serious morale difficulties; this created the core justification for continuing the offensive into October and November. Interestingly, the level of available German reserves did not feature in these assessments. This was because at the end of September 1916 the New Zealand Division had found a crumpled piece of paper revealing the Germans were not struggling to maintain their Western Front reserves. As the offensive petered out in poor weather, and the British looked towards a 1917 campaign, further information about German casualties, and continued indications of poor morale, gave GHQ grounds to argue that their opponent had been gravely damaged by the 1916 fighting.

The search for good news

Overall, it is clear that intelligence mattered in 1916. It would matter even more to the British in 1917 and 1918, but during the battle of the Somme it became a major factor influencing both strategy and operations. Though the intelligence system was far from perfect, it was now delivering potentially useful insights into the intentions and state of the German army. But we can also see a great deal of opportunism in the analysis, with Charteris and others seizing upon small indicators and then extrapolating favourable interpretations from them. We can also detect their analytical focus shifting continually in search of good news: from German reserves, to politics, and then to morale. In 1917 this lack of discipline would undermine the credibility of GHQ Intelligence and put them into direct conflict with the War Office over the true state of the German army.