The South African War was candidly described by colonial Australian soldiers.

The South African War was the first large-scale British war in which a majority of the British troops were literate. The siege of Elands River post in August 1900, in which five hundred colonial troops defied two thousand Boers, was just the sort of incident that led colonial Australian soldiers to put pen to paper. A striking aspect of their letters home is the candour with which they reported their experiences, even months afterwards. Through their words we gain insights into the largest of Britain’s nineteenth-century colonial wars – one fought with terrifying modern weaponry.

In the months prior to August 1900, British forces had occupied the capitals of the two Boer republics. After holding a council of war, Boer leaders had decided to continue their fight in the form of a guerrilla war. Without their capitals, Boer commanders in the field faced a constant struggle to keep their forces supplied. Through fast-moving raids on British forces, Boer commanders also sought to demonstrate to their dispirited compatriots that the British were far from invincible.

The Elands River post was a British outpost on a rocky ridge in the western Transvaal. As well as a telegraph station, the outpost contained a large amount of supplies, in the form of tinned meat, jam, preserved food, rum, and ammunition. A British column was ordered to collect these supplies and convey them to a better-defended position. Ahead of this column, a fast-moving force of 500 mounted British colonial troops was sent to guard the supplies.

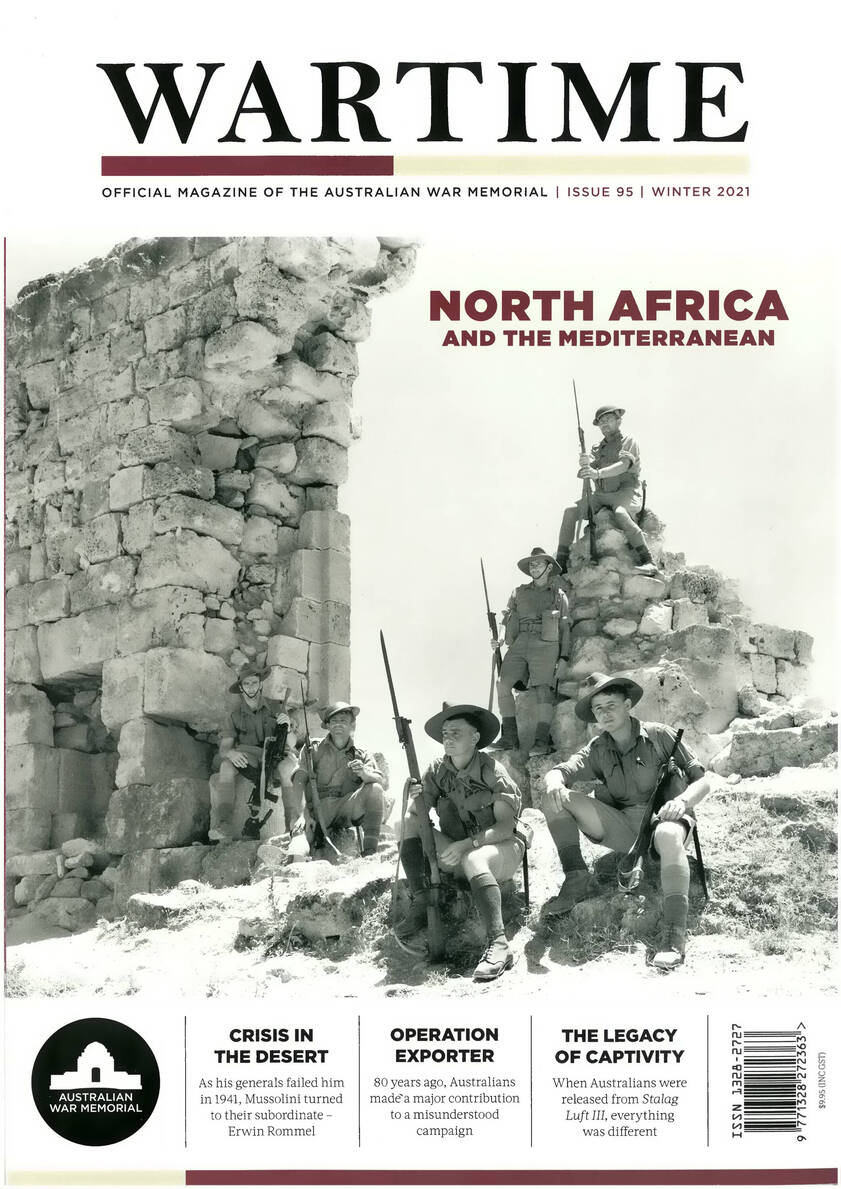

Queensland Mounted Infantry drying their kit after a storm, Belmont, South Africa, c. 1900. Photographers Underwood & Underwood, South Africa.

This force comprised about 300 soldiers from the Australian colonies, about 200 soldiers from the British colony of Rhodesia, and a number of native African porters. Troops from all the Australian colonies except South Australia were present, as well as a handful of British regulars and two Canadians. The entire force was under the command of a British officer, Colonel Charles Hore. During the siege of Mafeking, Hore had been second-in-command to Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, but now he was recovering from malaria and probably in no position to coordinate a defence against a motivated and outnumbering enemy.

The outpost lay on a stony rise surrounded on three sides by the Elands River and two tributary creeks. On 3 August, Captain David Ham ordered some of the Victorians under his command to dig in, warning them that an attack could take place at any time. Finding the soil tough and rocky, and with unsuitable shovels, the men only managed a trench of six inches (15 cm) depth. Feeling futile, one wag scratched some words on a piece of slate at the site: “Erected to the memory of the Victorians who were compelled to dig this trench. Fort Funk, 3 August 1900.”

There was no sign of Boers. The colonial garrison expected the larger column to relieve them the next day, and that night they held a singing concert around campfires. During this concert, a large Boer force under the command of General Koos de la Rey was silently moving into position surrounding the outpost. Estimates for the size of the Boer force range from several hundred to more than two thousand men, and over the course of the siege their numbers fluctuated. The Boers used the light of the garrison’s campfires to take the range for their nine artillery pieces.

Opening salvo

At dawn on 4 August, de la Rey’s men opened fire on the outpost. As Private Leslie Donkin, 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry, put it: “We were just sitting down to breakfast when a 12 lb. shell rudely interrupted it. There was a general rush for our trenches, which were anything but shell-proof, but helped to save a lot of lives.” The second shell the Boers fired destroyed the telegraph wires, removing one means of communication from the men at the post.

The Methodist Reverend James Green from New South Wales was the only chaplain present. In his 1902 book, he provided an eye-witness account of the siege. He experienced the full horror of being pinned down under superior firepower, and wrote:

It is easy to generalize, and also to throw a glamour over an engagement, but the truth should be told. One has to be in an engagement to see what ‘the glorious death of the soldier’ really is in these times of modern artillery. One man was lying with an arm blown away, and a great hole in his side such as is made in the earth with a shovel. As I lay by his side, the shells flying over us, he rocked from side to side in his agony. The other wounded man was lying with a leg completely shattered.

The first man described was Corporal Charles Norton, 3rd Victorian Bushmen, who died shortly afterwards. The wounded man, Trooper Frank Bird of the same unit, had his right leg amputated and survived. The garrison was fortunate to have among its number Captain Albert Duka, a surgeon with the 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry, who was later awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his tireless work tending the wounded. As for Trooper Bird, his leg was buried, then quickly dug up when he remembered that there was £4 in the pocket.

Another witness to the wounding of Troopers Bird and Norton was Trooper Walter Smith of the Western Australian Citizen Bushmen. His frank letter to the editor of his local paper only a few months later makes for grim reading.

I immediately rushed to Bird’s assistance, and as I lifted him from the ground with the intention of carrying him to the hospital I found that his leg was hanging by about half an inch of skin and flesh; the sight of this was too much for my nerves, and I had to lie him down again on the ground, and then another Victorian and I rushed away and had the doctor and the ambulance sent down to their assistance.

Queen’s South Africa medal. Lieutenant Thomas Moore, NSW Citizens’ Bushmen, was awarded the DSO during General Carrington’s failed relief attempt in the early days of the siege.

The effects of the Boer artillery made lasting impressions on other soldiers. Captain James Thomas, New South Wales Citizens’ Bushmen, witnessed Troopers James Duff and John Waddell killed by pom-pom fire within a short time of each other. In September he reflected on it in a letter home: “My poor boys – I thought – there will be a lot more of us join you before the day is over.” Trooper Thomas Gordon of the 3rd Queensland Mounted Infantry recalled the death of fellow Queenslander Lieutenant James Annat. “[The shell] burst between his feet. Poor fellow it made an awful wreck of him. He died inside half an hour.” Gordon remembered the first day of the siege as “one continual roar of guns & shell bursting and confusion; the air was thick with dust and smoke & flying scrap iron – I wonder that any of us survived.”

On the second day of the siege, the Victorian Captain David Ham counted 600 Boer shells between dawn and 10 am. Trooper Smith described the scene on the night of the first day of the siege:

There were hundreds and hundreds of horses lying dead and wounded, some of the poor unfortunate brutes had their sides cut clean open, others had their heads blown off as far as the shoulder, whilst others had their fore-legs broken and blown off, and others had hind quarters literally severed from their bodies; such a mass of flesh and blood was something awful to see, and the blood was actually trickling down the hill in small streams. Such are the horrors of war.

The Vickers Maxim one-pounder quick-firing gun, known as a pom-pom gun from the sound it made when firing, was a formidable anti-personnel weapon that allowed the Boers to maintain their principal advantage of mobility. The Boer forces at Elands River used three pom-pom guns and six field artillery pieces to great effect, killing almost all of the estimated 1,500 horses and transport animals in the garrison over the duration of the siege.

Lieutenant Richard Zouch, of the New South Wales Citizens’ Bushmen, lost all three of his horses to a single shell on the first morning of the siege. The next shell, from a pom-pom gun, “blew up my tent and scattered all my things to the ‘winds’. I had only just run out of it. The only wonder is that we were not all killed.”

Lieutenant R.E. Zouch, NSW Citizens Bushmen. His descendants fought in the First and Second World Wars.

Men of 1st NSW Mounted Rifles with a captured Boer pom-pom gun, c. 1901. Photographer unknown.

Water

Zouch was in command of one of two kopjes – hills rising suddenly out of the South African veld – that overlooked the water supply for the garrison. The southernmost of these was occupied by Captain Sandy Butters of the Rhodesian contingent, with about 80 soldiers. These two kopjes were the key to the British position: if the Boers could capture them, the colonial forces would have no access to water and would be forced to surrender. The Boers launched assaults on Butters’ kopje on 6 and 7 August, both of which the colonial troops successfully defeated, with defensive fire provided by Zouch’s men. Each night, colonial water-collecting parties suffered casualties from hidden Boer marksmen as they crept from these two kopjes to the creeks below. Their efforts kept the garrison supplied with enough water to drink, thus allowing the besieged defenders to maintain their stand.

Over the twelve days of the siege, two British relief columns were turned back by Boer artillery and marksmanship. After a few days, General de la Rey sent a messenger under a white flag with an offer for safe passage if the colonial troops surrendered. Colonel Hore sent a message back, the exact wording of which has been variously remembered. Captain Ham reported that the message read: “[This outpost] is held by colonial troops of Her Majesty, and we refuse to surrender.” The siege continued, but de la Rey’s attention was now becoming divided. Local Kgatla people were waging their own campaign against Boer farms in the vicinity of Elands River, burning buildings and seizing cattle. The Boer commander detached some of his men to quash these activities.

Relief

Finally, on the 16th of August, with the approach of a relief column of 10,000 British troops under Lord Kitchener, the Boer forces gave up their hopes of capturing or destroying the stores. The siege had been lifted. Eight Australians died during the siege or from wounds, along with seven other colonial soldiers and seven African porters.

Unidentified members of the NSW Imperial Bushmen in the Transvaal, possibly Ottoshoop, September 1900. Photographer unknown.

The historian Craig Wilcox remarks, “Australia had lost eight men defending a mountain of beef, jam and rum.” Indeed, the stores are central to the story of Elands River. Denying them to the Boers was a tactical blow to Boer forces in the Western Transvaal region. But the British had made a series of errors too. Multiple British columns converging on the Elands River post meant that mountain passes into the rugged Magaliesberg range were left unguarded. Seizing his opportunity, the wily Boer commandant Christiaan de Wet and his forces slipped through the tightening British net. Commandant Koos de la Rey, commanding the forces at the siege, also managed to evade the British with his men. Neither general was captured by the British. These men were to fight on to the end – true “bittereinders”.

Private George Horton, relating the events of the siege in a letter home to Queensland, wrote: “Ah, mother, it is a shocking affair all through. I wish from the very bottom of my heart that it was all over. I think this is the last big fight we will have, as the Boers seem to have had enough of us.” Like many on the British side, Horton thought the war was practically over because both Boer capitals had been occupied. As it turned out, the British generals had overestimated the effect this would have on Boer morale. An increasingly bitter war stretched on for nearly two more years, characterised by Boer guerrilla tactics and a brutal British scorched-earth program.

This article was originally published in Wartime Issue 95, Winter 2021.