The 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War makes us reflect on the events of 1945.

It was a victorious year of high achievement by all services. Yet it was also a year of high casualties – only 1942 and 1943 saw more Australians die serving than the 6,820 who perished in 1945. With the end of the conflict so close, these losses were especially poignant.

The deaths were also tragic because in many cases they were arguably unnecessary, particularly those occurring when the army attacked Japanese bases that had become strategic backwaters. Our evidence for these campaigns is plentiful: records were better kept, more photographs were taken and, until recently, it was possible to interview many more participants of those campaigns than earlier ones.

Although sources abound for 1945, the Duke of Wellington’s famous analogy between writing the history of a battle and the history of a dance still applies: it’s impossible to do justice to all perspectives or obtain all the facts.

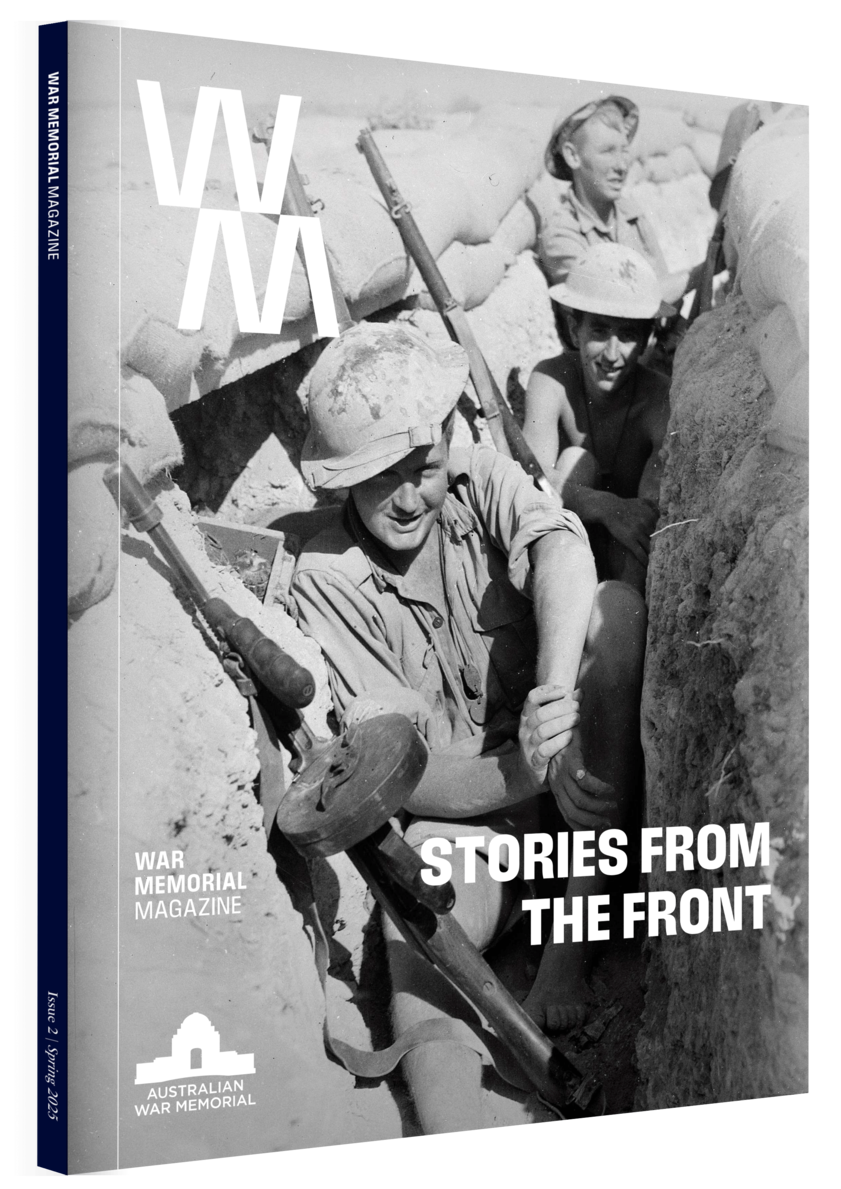

Soldiers of the 2/8th Battalion prepare to attack Japanese defences on Mount Shiburangu, near Wewak in June 1945. Though assisted by airstrikes and artillery, the infantry had to capture at least 20 bunkers. Photographer unknown.

Though many Australians were fighting in Europe that year, especially in the air, this article focuses on operations in the Pacific in 1945. The Pacific is a massive topic in itself, with Australian forces involved in separate campaigns in:

-

northern New Guinea (called the Aitape–Wewak campaign after the beginning and end points of the fighting)

-

New Britain, where the Japanese had their great South Pacific base at Rabaul

-

Bougainville; and

-

Borneo, where two divisions made three major landings between May and Jul.

From Borneo to Bougainville

From Miri in Borneo to Buin in Bougainville is about 4,800 kilometres – 2,000 kilometres more than the distance from Paris to Moscow – a vast area over which to transport troops and supplies, and provide air cover. Although there is a lot of sea in between, it is also an immense area over which troops had to march. The RAAF supported these operations and flew independent ones, especially in the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines.

The RAAF provided vital assistance to Australian soldiers fighting in the jungles during the final campaigns of the Second World War. Photograph by John Harrison

As these campaigns were all in tropical climates, much of the fighting occurred in dense jungle. In January 1945, Private Arthur Wallin of the 2/5th Battalion was in New Guinea. He wrote in his diary that once he entered “the dim lighted jungle, dripping foliage squelching mud and water, I often feel sort of depressed and suffocated. Maybe memories of other days patrolling along similar tracks always waiting for that ambush to be sprung on oneself.”

Wallin was conscious of similarities with earlier campaigns, which raises the obvious question about 1945: in what ways was campaigning in that year different from the war’s earlier years?

One difference is that in 1945 the Allies were clearly going to win the war, and the campaigns being fought by Australians would not be crucial to victory. Australians in northern New Guinea, Bougainville and New Britain had taken over from American garrisons, who were thereby made available for campaigns closer to Japan. The Americans had been content to leave their Japanese opponents to wither on the vine, whereas Australia’s military leaders – notably Commander-in-Chief General Blamey – felt that Australians in these areas needed to be more aggressive. In August 1944 he stated that the coming campaigns of 1945 would involve the army making its “maximum effort during the war”. The landings in Borneo were of similar dubious significance to the war’s outcome, but the American commander in the South-West Pacific, General MacArthur, was keen for them to proceed. Australian troops on the ground could have been expected to be half-hearted in approaching the fighting, which has been called “an unnecessary war”.

The hard slog

The 6th Division, the first division raised in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2AIF), was in northern New Guinea from the first day of 1945 till war’s end. General Blamey sent the division there because he wanted to give this elite formation a substantial task after a long period of inactivity – more than three years for some units. Some felt this was sending men “on a boy’s errand”, but that it was preferable to “everlasting training”. The Australians were outnumbered by a force of about 35,000 Japanese, but were far better equipped and supplied than their enemies, for whom food shortages were a huge problem. The Australians had naval and especially air support, but knew that their campaign was a low Allied priority and that the strategic value of the operations was dubious. Nevertheless, as the official historian later acknowledged, in each attack veterans and young soldiers “performed deeds of fine gallantry”.

While Japanese sources on these campaigns are not plentiful, Major Masao Horrie, a staff officer with the 51st Division and 18th Army Headquarters, cast doubt on that gallantry when he claimed, “If we were in the same position the Australians were in … 1945 in New Guinea, around Wewak, we would not have hidden in holes and let the artillery do the job … The Australians never charged.” This judgement seems harsh. Although the 6th Division was notoriously miserly in the distribution of medals, its men won many decorations for gallantry in this campaign, including two Victoria Crosses.

Private James Oliver, 31/51st Battalion, carries a cross to mark the grave of a fallen comrade, Bougainville, February 1945. Photograph by Jack Band.

One of those, posthumously awarded to Lieutenant Bert Chowne, involved him knocking out two machine-guns with grenades before leading his platoon in a charge. The division did indeed use its superior firepower to minimise casualties, and casualty numbers for the campaign are telling. In 10 months the Australians in New Guinea lost 442 killed in action, the Japanese 9,000, a ratio of 20:1.

In the same period Japanese forces were driven from 7,700 square kilometres of ground and the 6th Division advanced more than 110 kilometres, overcoming great logistical challenges while undertaking dual advances along the coast and in the mountains.

Publicity for the Aitape–Wewak campaign struck the participants as inadequate. The same applied with even more force in Bougainville, with the involvement of Australian troops not mentioned in the Australian press for six months.

When the Australians set up headquarters at Torokina on Bougainville, they estimated enemy strength at 18,000. In fact, it was about 40,000, many more than the Australian force comprising the 3rd Division and two independent brigades. In accordance with Australia’s aggressive approach in the final campaigns, they launched three offensives, in the south, north and centre. Historian Karl James rightly dubbed the campaign “the hard slog”. It involved battalions that were originally part of the Militia, known at the time as the Citizen Military Forces (CMF).

As most of the troops in those battalions volunteered for the AIF while in the Militia, these units gained AIF status, but that’s not the way many people identified them. One of these battalions, the 9th, was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Geoff Matthews, who kept a diary. Here one can trace his unit’s passage from being “excited and glad to get into it” in November 1944, through to developing a “constant sense of danger” by January 1945, when large numbers of men refused to go on patrol or attack. They welcomed a break from the line in February, but when they returned to fighting, Matthews used phrases such as “the jitters” and “dropping his bundle”, and referred to threats that men “would not go on”, and having to avert a “sit down strike”.

Members of the 9th Battalion preparing to attack Japanese positions on Little George Hill, Bougainville, 29 November 1944. By February 1945, when the battalion was withdrawn for rest, many men were suffering from combat fatigue. Photographer unknown.

A diary kept by a private in the 9th’s sister battalion, the 61st, shows similar problems:

“The Bn is in a bad way as the men are all cracked up. Today 9 from ‘D’ Coy and 3 from ‘B’ refused to go on patrol, and I believe that ‘A’ Coy patrols only go 200 yds out and sit down. If they send us in again the Coys are going to refuse to go. So things are in a very bad state. Already two officers have been sent back for standing up for the men. Nearly all the boys have a vacant look in their eyes and look dazed.”

So what was happening on Bougainville in 1945? These two battalions comprised over 1,000 men. How representative were they? These battalions were of the original CMF, whereas most units that saw front-line service were originally AIF. There seems to be no evidence of entire campaigning AIF units even considering disobeying orders. However, on the only occasion that they fought alongside AIF units, at Milne Bay in 1942, the efforts of the two fledgling Militia units did not suffer by comparison with the veterans. Moreover, in 1945 neither unit seems to have been held by senior command to be in disgrace. Indeed, senior officers, including General Blamey, gave the unit high praise in May–June 1945.

"Some mighty work done"

The general editor of the Official History of Australia in the Second World War, Gavin Long, wrote that the AIF veterans in the Aitape– Wewak region were less enthusiastic than the Australians on Bougainville, making this assessment despite having access to Matthews’ diary. This experience of the Australians on Bougainville relates to the fact that, in all armies, combatants are on a slippery slide to breakdown. Whether the slide tended to be unusually fast, propelled by some internal dynamic, in original CMF units is a matter for conjecture. Blame for the undisciplined behaviour in the two battalions belongs primarily to authorities, who were too slow in recognising when soldiers had been driven beyond the limits of military efficiency, and beyond their capacity to endure.

Private J. J. Ryan (left) wounded on Little George Hill, receiving medical attention from S45782 Private C. W. Summers. Photographer: Ronald Noel Keam.

Over 30,000 Australians served on Bougainville, and more than 500 were killed. As in New Guinea, many extraordinary acts of bravery were recorded, and two Victoria Crosses were earned. Lieutenant-Colonel Matthews recommended men for decorations, and justifiably reflected on “some mighty work done”.

On New Britain, the 5th Australian Division did a remarkable job, gradually occupying the whole of the island except the Gazelle Peninsula, with 42 killed and 122 wounded, and counting 206 Japanese dead. As Long put it, one understrength Australian division imprisoned an entire Japanese army in Rabaul. The 36th Battalion spent some 30 weeks in forward positions on the island – a unique record made possible by the relatively quiet nature of that front. Members of the original CMF battalions expressed pride in their status and achievements.

On 1 May the 9th Division’s 26th Brigade landed on Tarakan Island. Peter Stanley called the campaign “an Australian tragedy”, a term embodied by Tom “Diver” Derrick VC DCM, who died of wounds there. Through his courage, skill and leadership ability, Derrick had risen from an impoverished background to win two decorations and become an officer in his beloved 2/48th Battalion. He could have chosen to miss this final campaign, but wanted to go. A complex person, Derrick knew that he was lucky to have survived so far. He could be a difficult subordinate and a demanding leader, but was universally respected. People look back on his presence on Tarakan as a foredoomed enterprise, but he did not see it that way. His diary and surviving letters from that period show that he expected to survive. He talked of his morale being over 100 per cent, planned to get on the beer with his dad, and forecast the campaign ending in clearing patrols. Instead, Derrick died of wounds on 24 May. His, of course, was far from the only tragedy on Tarakan. More than 220 other Australians died there, as did more than 1,500 Japanese. The campaign’s main purpose was to open Tarakan airstrip to Allied use but, after capture, it was found to be so badly damaged as to be not fully operational by war’s end.

Lieutenant Albert Chowne VC MM, 2/2nd Infantry Battalion.

Lieutenant Tom “Diver” Derrick VC DCM, a courageous and thoughtful leader, was widely regarded as Australia’s best soldier of the Second World War. His death from wounds on Tarakan in May 1945 cast a pall over many in the army. Photographer unknown.

The fighting for North Borneo and Balikpapan was also arguably a misuse of some of Australia’s best troops. The cost was heavy, but was again much worse for Japanese forces. Here the Australians were conscious of their materiel superiority, which in 1945 was at an unprecedented level. A telling symbol of that superiority came at Balikpapan early in the initial advance, when a flamethrower burst silenced three Japanese soldiers in a tunnel. As the 2/16th historian noted, it was “pathetically symbolic of a lost cause” that a Japanese soldier tried to quench the flame with a cup of water. Balikpapan was the 7th Division’s smoothest campaign, with one of its commanders calling it “a short, sharp little show beautifully planned and carried out with dash and speed”. It cost the Australians 229 dead, the Japanese up to 2,000.

Men of the 2/16th Battalion use flamethrowers to clear Japanese snipers from a tunnel on Balikpapan, 1 July 1945. Photographer unknown.

Although men like Wallin, Chowne and Derrick were veterans of several campaigns, by 1945 most front-line troops were relatively new to their battalions. For example, when the 2/23rd and 2/24th Battalions went into action on Tarakan, more than half of the officers and men of the 2/23rd and 60 per cent of the 2/24th were entering their first campaign. By then, many veterans were, unlike Derrick, running out of reserves of enthusiasm. The old hands were still crucial, maintaining the ethos of each battalion and giving vital practical training and advice to the newcomers, but much of the energy required in the last campaigns came from the new men.

Some 20 RAAF squadrons of the 1st Tactical Air Force supported the Borneo landings, as did squadrons based in Australia. Many US aircraft were also allotted to the landings, especially at Balikpapan. While the threat from Japanese fighters had all but disappeared and the RAAF did not fight one single flying battle in 1945, enemy anti-aircraft fire was often formidable. Aircraft and crew losses were not balanced by losses inflicted on the enemy, and in April eight senior RAAF officers were so sick of the wastefulness that they tried to resign their commissions in complaint. The so-called Morotai Mutiny brought some reforms, but also reflected the frustrations that racked the RAAF.

A world without war

In 1945, Australian servicemen achieved formidable success on every front. After repatriation they had to adjust to a world without war. The official history notes that in 1944 and 1945, Australian soldiers felt increasingly isolated from the civilian world, and that on home leave they tended to seek each other’s company to reminisce and to complain about civilian Australia. I well remember meeting veterans of the 2/43rd Battalion in the 1980s, one of whom said how as a boy he’d been taught “Thou shalt not kill” but in 1945 had been ordered to kill, and done so. On returning to civilian life he found it hard to readjust. He and the other veterans had fought – and in all too many cases died – to enable the Australia they knew to survive and grow.

Author talk

Historian Dr Mark Johnston joined us at the Memorial to discuss the experiences of Australian servicemen at the front line in the last year of the Pacific campaigns.