What seemed like destiny became an experience that has lasted a lifetime.

In May 1968, on my first day in the army at Puckapunyal, one of our NCOs suggested where our future destiny might lie. “One in three of you will end up in Vietnam,” he correctly prophesied. It was a prospect that both daunted and excited me. But I had no way of knowing at the time that I would eventually be included in that number.

My early service had been in Malaysia with the 8th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (8RAR). Before going to Vietnam, we returned to Queensland for further training. From Shoalwater Bay, I wrote a letter home in October 1969:

We moved to Canungra, near the New South Wales border, for the final stage of our preparation for Vietnam. Canungra was tough. We ran the gauntlet of assault field courses – swinging on ropes across rivers, crawling under concertinas of catwire, and negotiating obstacle courses. The grenade assault course was interesting. We set out armed with rifle and webbing and six grenades, and ran the course over half a mile (800 metres), hurling grenades at selected targets. Our last course, Battle Efficiency, required us to cross an open field in sections of ten men with full packs and rifle, using a tactic known as section fire-and-movement – crawling through long grass, barbed wire entanglements and other obstacles. All around us mines and artillery fire exploded, covering us in flying dirt, while a Vickers machine-gun fired live rounds over our heads. However, no amount of training could fully prepare us for the real thing.

8RAR arrives in Vietnam, Nov 1969

[silent]

The 1st Australian Task Force was deployed in Phuoc Tuy Province, south-east of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) at a place called Nui Dat (“clay hill”), set in a rubber plantation interspersed with banana trees. Nui Dat had deliberately been established in the middle of Viet Cong territory to facilitate the counter-insurgency operations, to which Australian and New Zealand forces had been allocated. From Brisbane I flew to Vietnam with the 8RAR Advance Party, to help prepare for the arrival of the rest of the battalion, now at sea aboard the converted troop carrier, HMAS Sydney. Later I wrote to my family:

Even at that altitude it was easy to see this was an active war zone. My role as a rifleman serving on operations meant that contact with the enemy was not just a possibility, it was a certainty. When we landed, there were American soldiers everywhere. Next, we boarded a Hercules aircraft for the 20-minute flight to Nui Dat. The perimeter of the entire base at Nui Dat was encircled by three parallel concertinas of catwire. M60 machine-gun positions, placed strategically in sectors around the perimeter, were the responsibility of each battalion to maintain, as well as clearing patrols which swept beyond the wire at first and last light, when enemy attack was most likely.

Nui Dat was a large base. Three infantry battalions were serving there, supported by squadrons of tanks, armoured personnel carriers, field engineers, and various other elements. There were two chopper pads, a main airstrip and a unit of reinforcements camped near Delta company lines: soldiers waiting to be absorbed when needed into the three infantry battalions to replace soldiers killed in action, wounded, or lucky enough to be returning to Australia.

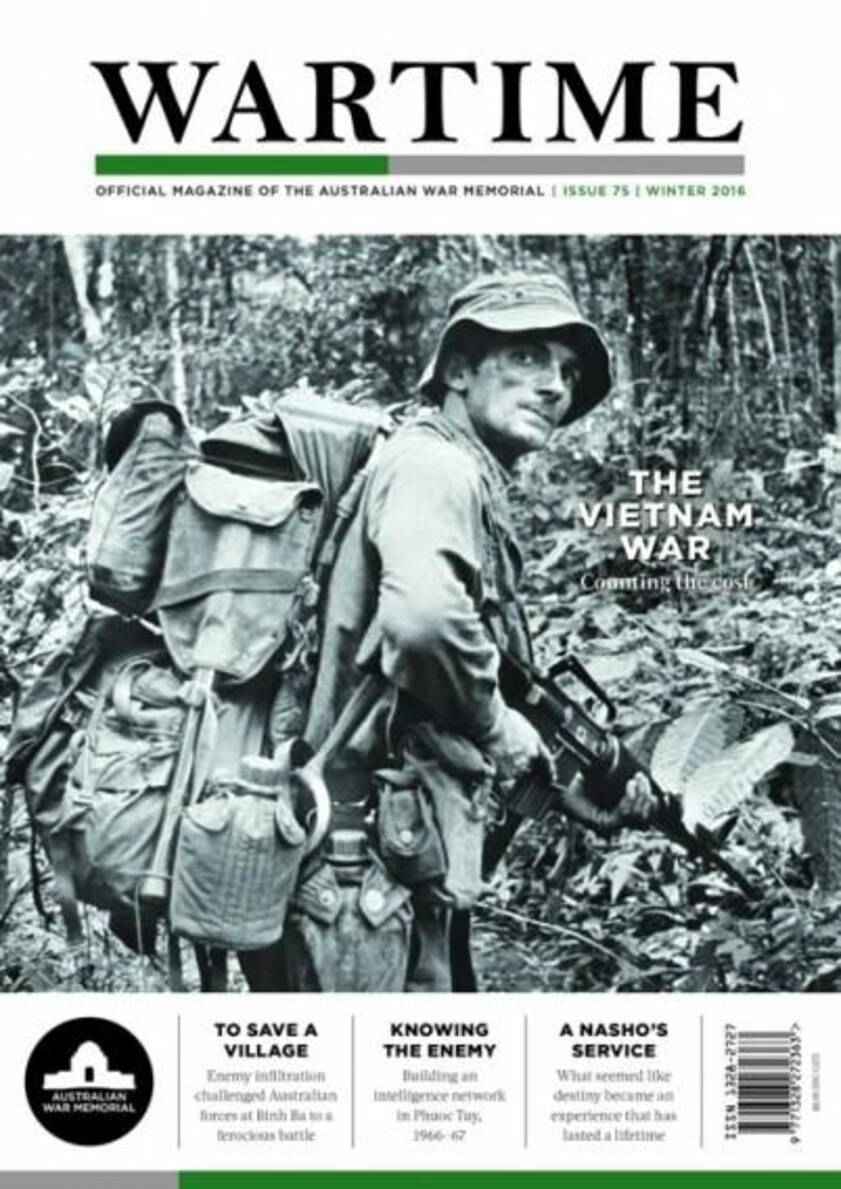

Sergeant Peter Buckney of D Company, 8RAR, patrolling in the dense jungle of the Hat Dich region of Phuoc Tuy during the battalion’s “shakedown” Operation Atherton in January 1969. He is carrying the soldier’s typical load for extended operations.

The battalion we were to replace, 9RAR, was winding down towards the end of a hard tour. We moved in and shared their lines for a week. I got to know some of the 9RAR blokes pretty well and they were a friendly though battle-weary lot. 9RAR had sustained a lot of casualties during their 12-month tour and, unsurprisingly, many of them seemed to us exhausted and homesick.

Three days after we arrived, a nasty “fragging” incident took place at Nui Dat. A platoon commander from B Company, 9RAR, Lieutenant Robert Convery, was killed when one of his soldiers placed a grenade in his tent late one night. The story went that the soldier held a personal grudge against the officer and had been drinking heavily just before the incident.

Soon after arriving in Vietnam I quickly came to realise this was a dirty, controversial war. It was far removed from the all-encompassing global conflicts of the two world wars, where support for servicemen and women was universal and unconditional. Many people back home, especially my friends, were ambivalent about what was going on in Vietnam. Many people just didn’t care. I resolved then and there to do my duty, to keep my head down, not to take risks, and to simply bide my time. I had already completed three quarters of my National Service obligation. I had no desire to return to Australia a dead hero in a body bag. I wrote about my first impressions of war in an early letter home.

Delta company lines were set close to the perimeter wire. Tents for 10, 11 and 12 Platoons were pitched under generous tree cover, with Company Headquarters and the company command post in an underground bunker innermost from the wire. At three points around the wire, each platoon had a gun pit – a room about 2 metres square enclosed and roofed with solid timber beams and sandbags to form a substantial structure. Inside each gun pit was an M60 machine-gun, a night vision scope, flares, grenades, and several “clackers” – hand ignition devices from which wires led to Claymore anti-personnel mines planted outside the wire. When we were in Nui Dat we were rostered for gun piquet duty one night in three, and manned the radio in the Delta company command post. We also undertook clearing patrols each day to clear the area for some distance around the base to ensure there was no build-up of Viet Cong activity.

I also went on a number of TAOR (tactical area of responsibility) patrols. These were carried out by sections of riflemen and were designed to deter the Viet Cong from attacking Nui Dat and to prevent the enemy from moving into the settled village areas of Phuoc Tuy Province. Leading the section were the forward scout and second scout, the most competent and alert guys, as the eyes and ears of the patrol. Next came the section commander (a full corporal), the gunner (carrying the M60 machine-gun) and the “number two” who, in addition to supporting the M60 gunner, also served as a rifleman. Four other riflemen completed the section, sweeping an arc on either side of the flanks of the patrol, with a “tail-end Charlie” sweeping an arc of 180 degrees to the rear.

Newly arrived soldiers of 8RAR en route to the task force base at Nui Dat after disembarking from the troop carrier HMAS Sydney at Vung Tau in November 1969.

Soldiers of A Company, 8RAR, move up to assault an enemy bunker complex in densely timbered country during Operation Atherton on 15 December 1969. The terrain and dense vegetation of the Hat Dich region often made such attacks dangerous and difficult. Photographer: Denis Gibbons

We wore leaf camouflage to break up body shape, and partially blackened our faces. Patrolling was mostly done in complete silence, communication with other members of the section being done through hand (or field) signals.

The patrols I went out on led initially across open paddy fields before entering the jungle, or “the Jay” as we came to know it. On these patrols, fear was a constant companion. It was fear of the unknown, fear of the silence and sounds of the jungle, and praying you wouldn’t step on a “jumping jack” mine. All the time we had to be “switched on”, vigilant, expecting the unexpected, peering through the dark glades of the jungle. At times the patrolling was monotonous and it was easy to fall into complacency, though there was always a constant edginess.

Our first “contact” was almost over before it began. Our forward scout detected enemy movement and called out, “Contact right!” I instinctively went to ground, accompanied by a rush of adrenalin. I was shaking so much that I could scarcely line up the fore and back sights of my rifle. Nevertheless, I fired off two full magazines into the Jay as the rest of the section opened up at the same time in a cacophony of gunfire. When it was all over the VC had melted away. I am ashamed to say it was the most exciting moment of my life.

These were casualties: two Delta Company soldiers were wounded, and a gunner from 12 platoon was killed when his webbing became entangled in undergrowth. In an attempt to pull himself free, he fell into a “fire lane” – an open and exposed area – and was immediately cut down by enemy fire. Back at Nui Dat I was given the job of cleaning his M60 machine-gun. The feed cover, made of heavy gauge steel, had been deeply cut and gouged by impacting enemy bullets. When I opened the breech, a mixture of blood and oil poured out. At the end of our patrols, when we got back to Nui Dat the first thing we did was to fire all unused ammunition into a deep pit. We always set out on each patrol with fresh ammo, as no chances could be taken in case a dirty or rusty round should jam during a contact. It was always a palpable relief to arrive back at the base, another patrol over, another one survived. We looked forward to 36 hours’ rest and convalescence leave in Vung Tau, but somehow you didn’t feel safe in that town – you didn’t know who was on your side and who was not.

Vietnam was suffering the visible agony of a country under occupation. The Vietnamese people we saw in towns and working the fields all had that haunted, hunted, war-weary look in their eyes. For them life held no future, no certainty, no stability. They lived their lives from day to day, constantly under the shadow of violent military activity and trying their best to keep out of harm’s way and somehow survive the war. Vung Tau was no exception, and it was common knowledge that the seaside resort was used by the Viet Cong as well as the and Australians.

An Australian Army issue kitbag.

In early 1970 we got news that all soldiers from our National Service intake were to return to Australia in February. It was some of the best news I ever received in my life. The days counted down slowly and we took no chances when out on patrol. Then early one morning at Nui Dat we changed into our civilian clothes and climbed into trucks bound for Luscombe Field airstrip. Our spirits were high as we boarded a Caribou aircraft to Saigon airport for the flight back to Australia.

We touched down at Sydney airport at midnight. Our arrival was a low-key affair to avoid attention and controversy, as the Vietnam Moratorium protests were now in full swing. But it was a disappointment nevertheless. No welcome home or ticker tape parades for us. We were spat out onto the cheerless streets of Sydney in the early hours of the morning and left to fend for ourselves. I managed to check into a nearby hotel for the night. It was a very strange feeling. Eight hours before I had been in jungle greens in Nui Dat waging war, now I was lying in a Sydney hotel room, alone with my thoughts. It was almost as if Vietnam had never happened.

My war was over, but within weeks, my sense of commitment to my unit hit me in unexpected ways. I was overwhelmed by an unexpected sense of duty to my mates in Vietnam; this feeling became worse on hearing of the mounting list of 8RAR casualties, especially in the wake of a big stoush in the Long Hai Hills with the battle-hardened local Viet Cong D445 Battalion. All my friends had jobs and were spending their weekends playing sport, socialising and going to parties. The difference was the change in me. I was proud to have fulfilled my duty.

I had seen so much of the reality of life and death that I seemed to have little in common with them. I had returned physically and mentally intact. I was lucky. I had got through it okay and returned safely to Australia without the effects and disabilities that befell some of my mates. But I knew men who had lost limbs, and one who later founded a successful business and a family, only to take his own life.

When I began my National Service, it felt as if I had been given a two-year jail sentence. The months dragged by at a snail’s pace; I couldn’t wait to reclaim my civilian freedom. But at the end of my last day in the army, 2 May 1970, it was with a sense of genuine regret, even sadness, that I folded up my army greens, took off my boots and packed away my slouch hat for the last time. My time in the army was an amazingly profound experience that would shape the rest of my life. There hasn’t been a day since when I haven’t thought and reflected on Vietnam.