After the war, an experienced Australian nurse served with the United Nations at the infamous camp.

Portrait of Principal Matron Muriel Doherty, RAAF Nursing Service at Air Force Headquarters (AFHQ), Victoria Barracks.

There had been unimaginable horror, but now there was dancing. Just months after the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, men and women who had been subjected to cruelty, starvation and neglect at the hands of the Nazis were celebrating their freedom with an impromptu ball in the corridors of the hospital where they were being nursed back to health.

Far from discouraging it, Principal Matron Muriel Knox Doherty watched her patients with delight. “The old piano squawked bravely above the drums, and the pulmonary Tbs [tuberculosis patients] danced with anyone who came along,” the Australian wrote. “Girls with legs in plaster discarded crutches and pirouetted around, young men in the dreadful striped concentration camp pyjamas (which I have been unable to have dyed) swirled round with Gypsy women in colourful long, full skirts, and the visitors joined in. I even saw one or two of the German cleaning women taking part surreptitiously. The noise was awful and everyone enjoyed themselves immensely.”

By mid-1945 the war in Europe was over, and the massive task of rehabilitation – of people, nations and economies – was under way. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) was the principal organisation responsible for enabling affected countries to readapt to peace. It had been established in late 1943, and Australia was one of the original 44 member countries (by 1946, 48 governments had signed on). UNRRA appointed highly skilled specialists in areas including transport, supply, health, industry and agriculture. With an “irresistible urge” to help the plight of millions of displaced persons, Doherty resigned her position as Principal Matron of the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service and joined UNRRA.

Born in Melbourne in 1896, Doherty had been a Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment during the First World War, and worked at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPA) in Sydney. She later undertook her nursing training there, graduating in 1925 and working in the hospital’s gynaecology ward before being promoted to sister-in-charge. In 1930 Doherty travelled to England and worked as a private nurse in Britain and on the Continent. She began a Sister Tutor course in 1932 at King’s College of Household and Social Sciences at the University of London. Afterwards she returned to the RPA, where she was responsible for establishing a school of nursing.

Doherty was appointed a staff nurse in the reserve of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in August 1935. She was called up at the outbreak of the Second World War, and made a Sister Clerk to the office of the Principal Matron of the AANS. In 1940 she became Matron of the Royal Australian Air Force Nursing Service and was in charge of Number 3 RAAF Hospital, Richmond, NSW. She ultimately became Principal Matron and Wing Commander.

Matron Muriel Doherty, RAAFNS, Alfreda Markovitch, 1948, oil on canvas, 84 x 71 cm

At Bergen-Belsen

Doherty was one of 40 Australians to serve in UNRRA’s international workforce – at its peak, there were 12,000 staff. She flew to England with no certainty of what role she would play, but was quickly recognised as best suited to the position of Matron of the Bergen-Belsen hospital.

German military authorities had established the Bergen-Belsen camp – named for its location near the two small towns – in 1940. It was exclusively a prisoner-of-war camp until 1943, but then became a concentration camp. At various times the camp complex held Jews, prisoners of war, political prisoners, Gypsies, criminals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and homosexuals. As Allied and Soviet forces advanced into Germany from late 1944, Bergen-Belsen was inundated with thousands of Jewish prisoners cleared from camps closer to the front. Food rations in the camp began to shrink, and overcrowding and poor sanitary conditions led to outbreaks of diseases including typhus, tuberculosis and dysentery. In the first few months of 1945, tens of thousands of prisoners died.

British soldiers liberated the camp on 15 April. At that time the camp held more than 60,000 prisoners who had gone one week with no food or fresh water, after a long period of being deliberately malnourished. Thousands of corpses lay unburied on the camp grounds, and most of the inmates were seriously ill; thousands more would die after liberation. The camp survivors were evacuated as soon as practicable to a nearby German military barracks. It was here that they were nursed back to health and lived as displaced persons while efforts were made to repatriate or resettle them. British forces torched the original camp to prevent the spread of typhus.

Children sick with typhus sleep together in their wooden cots in the concentration camp.

The entrance gate to Camp No. 1 at Belsen concentration camp. Note the sign which reads "Dust spreads typhus 5 MPH".

Doherty arrived at the barracks hospital in early July 1945. She had begun documenting her UNRRA experience from the moment she left Australia, and during her tenure at Bergen-Belsen she wrote long and detailed letters home to her family and friends about what she referred to as “the most worthwhile job of my life”.

There were many challenges from the start. UNRRA was initially disorganised and slow to make the necessary arrangements for medical and nursing staff to take over from the British Army, which ran the hospital. Doherty had to sort out accommodation for the new medical staff, hire cooks and cleaners, plan meal and duty hours for staff, and arrange transportation. She was given too few nurses to do the work, and a hospital with many deficiencies in medical equipment and supplies. There was also the challenge of managing a team of people who spoke many different languages, and handling resentful locals who did not wish to help.

The patients – who were by this time mostly past requiring acute care and were in various stages of convalescence – presented unusual difficulties. Their tendency to hoard food attracted thousands of flies to the wards; and the hospital’s bedlinen regularly went missing as the enterprising fashioned them into clothes. Displaced persons, and guards, would also regularly steal household items, clothing and food from the hospital and stores for their own needs. But Doherty was understanding and largely forgave their transgressions because of the horrors that they had lived through. “One can understand that these people who have struggled so long for existence still must gather all they can. Wouldn’t you?” she wrote. She further allowed the camp survivors to make cheese in the wards; encouraged them to make handicrafts from what scraps and items they could find; and she willingly attended their weddings, baby christenings, and solemn memorial services for those who had died. “I felt nothing we could do for them could ever compensate,” she wrote.

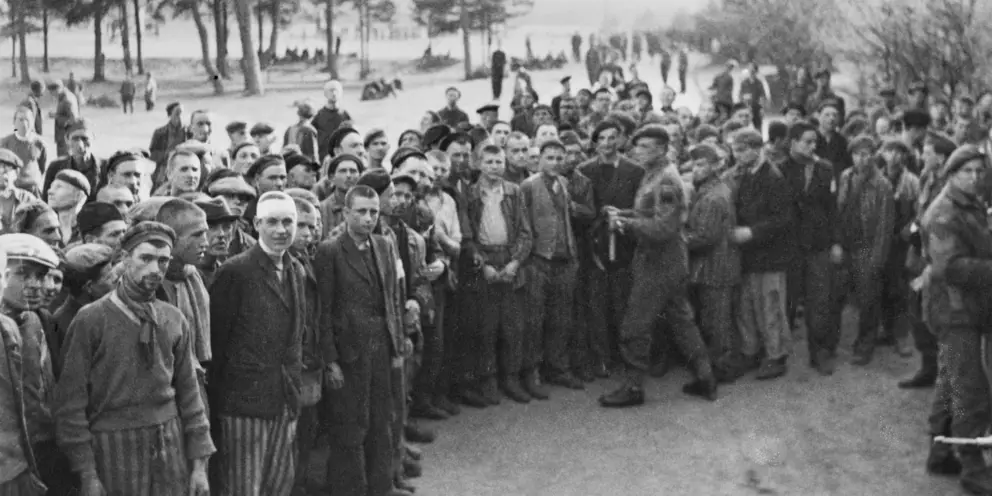

The crowd of male inmates of Belsen concentration camp that had gathered as British soldiers arrived, three days after the liberation of the camp on 15 April 1945.

Female inmates of Belsen concentration camp sitting on the floor of a crowded hut.

A view of one of the women's camps within Belsen concentration camp. Women are standing and waving at the barbed wire fence, and there are other women running towards the fence from the huts in the background.

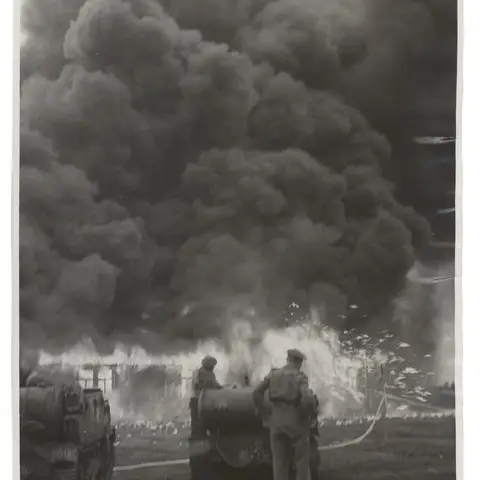

British soldiers burn the final remaining huts at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp to avoid the spread of typhus.

At the trials

Besides detailing her work and the experiences of her patients, Doherty gives a fascinating account in one of her letters of a day she spent in Lüneburg observing the trials of Bergen-Belsen staff. There were 48 men and women facing charges of war crimes committed there and at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Among them was Commandant Josef Kramer, who had been the head of both camps at different times, and the camps’ doctor, Fritz Klein. The trial took place before a British military tribunal. Doherty, visiting about two weeks after the trial began, described the prisoners in the dock:

They were dressed either in old SS uniforms without badges, or as civilians, and were the most menacing and degenerate-looking lot of human beings I’ve ever seen together ... It is said that each of these accused is responsible for at least 1,000 murders.

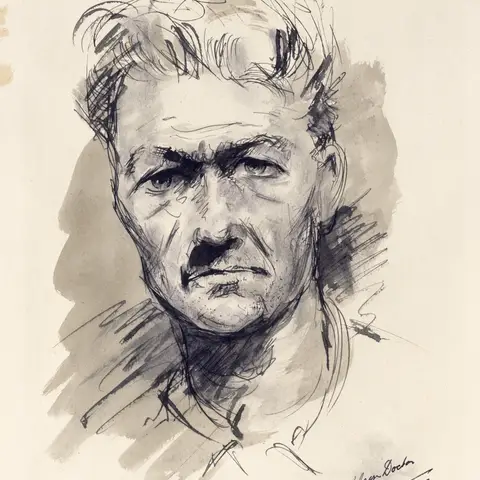

Belsen doctor, Alan Moore, 1945, pen, brush and ink on paper. Fritz Klein was the Bergen-Belsen Camp doctor who subjected prisoners to appalling medical experiments and would later hang for his offences.

A witness who gave evidence that day detailed the work he had been forced to do in the crematorium at Auschwitz, where thousands of people were gassed and killed every day. Another former prisoner testified that three days before the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, he and his starving friends were in the cookhouse scrounging for food when Kramer entered and shot his two friends dead and wounded him in the hand. And a third witness said she had been part of the camp band that was made to play at public hangings, and during the selections of prisoners who would be sent to the gas chamber at Auschwitz. “She identified Kramer, Dr Klein ... and others, and when she had finished giving evidence, stood for fully three minutes, just looking at them in silence. What a moment of triumph!” Doherty wrote.

Kramer and Klein were two of 11 defendants sentenced to death by the tribunal. Another 19 defendants were convicted and sentenced to prison terms; the tribunal acquitted 14. On 12 December 1945, British military authorities executed Kramer, Klein and their co-defendants.

Doherty spent one year at Bergen-Belsen before she was sent to Poland to assist in nursing education there. She returned to Sydney in 1946. Her letters from Bergen-Belsen are immensely valuable in helping us understand the experiences of survivors of the concentration camps, and of those who worked to heal them. She was a champion of those “who have no home, no families and no country to which to return, and who have had everything that was worthwhile in their lives taken from them and have been through hell.”