A colonial artwork in the Memorial’s collection has its roots in brutal frontier warfare.

This article includes racist terms from historical records that reflect social and political attitudes of the period in which they were written. These terms are offensive and should not be used today.

In 2019, the Australian War Memorial acquired a lithograph print of an early piece of government propaganda from colonial Van Diemen’s Land, now known as Tasmania. The print was acquired following the Memorial’s National Collection Development Plan, which identifies material relating to frontier violence, as well as lithographs depicting colonial-era soldiers, as items for collection.

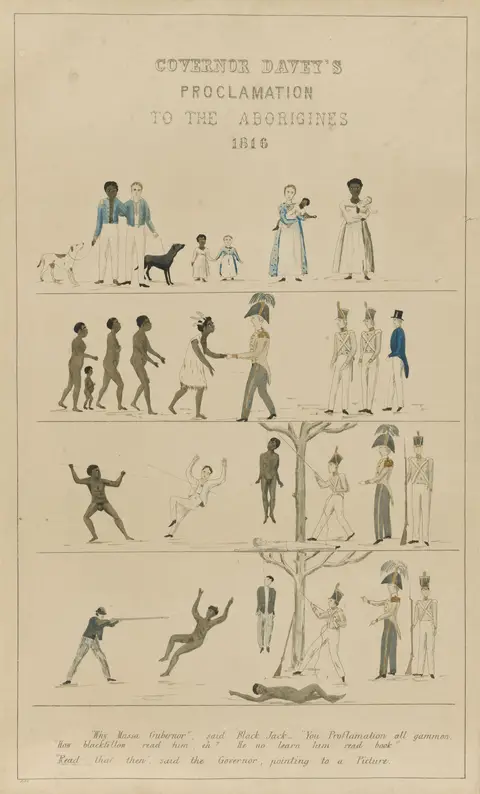

Alfred Bolter, Governor Davey's Proclamation to the Aborigines, 1816 (c. 1866, lithograph, 48 x 28 cm)

This print was made for the Australasian Intercolonial Exhibition, held in Melbourne in 1866. The lithograph is based on proclamation boards that were originally authorised in about 1830 by Lieutenant Governor George Arthur, not his predecessor Thomas Davey.

The title printed on the lithograph, referring to Governor Davey and 1816, was added for the Exhibition in the 1860s. The engraver had the wrong date and wrong governor – precisely why he made that error has been cause for conjecture by modern historians.

Removed from its historical context, the 1866 lithograph is a deceptively simple artwork to interpret, at least for non-Indigenous audiences: if everyone in Van Diemen’s Land follows British law, it seems to say, then everyone will be protected by British law. Understood alongside other proclamations from the same era, however, the lithograph tells a story of war, dispossession, and British colonial law.

The lithograph is divided horizontally into four panels. The top panel shows Aboriginal people and Britons living in harmony. The second panel shows a meeting of the two societies; the British are represented by the lieutenant governor, soldiers, and a free settler or civil officer, while the Aboriginal Tasmanians are represented by a chief, adults and a child. The lower two panels illustrate the application of British law, at least in theory. The punishment for spearing a settler would be hanging; likewise, the punishment for killing an Aboriginal person would also be hanging. The written anecdote at the bottom did not appear on the original boards, but was added to help the audiences of the 1860s understand the purpose of the boards. The anecdote itself is an example of mid-nineteenth-century racism, casting an imagined “Black Jack” in conversation with the governor about written proclamations:

“Why Massa Gubernor,” said Black Jack, “You Proflamation all gammon. How blackfellow read him, eh? He no learn him read book.”

“Read that then,” said the Governor, pointing to a Picture.”

Origins

The origin of the proclamation board was central to a dispute between two prominent Tasmanian colonists about the early history of conflict in the colony. This debate played out in the Hobart Mercury in the 1870s. Former Surveyor-General James Erskine Calder wrote a detailed letter to the editor showing that the boards were originally made in 1830 on Governor Arthur’s orders. Tasmanian civil servant Hugh Munro Hull, who had organised the colony’s exhibits for the Exhibition in 1866, wrote to the Hobart Mercury in the 1870s to identify himself as the person who had added the title referring to Davey and 1816. He claimed a now-deceased schoolmate of his, a woman who had been in Hobart since the first year of British colonisation, had told him the boards dated from Davey’s time. Researchers since then, however, have shown Calder to have been correct. It is possible that Davey had ordered similar pictures made during his time, as remembered by Hull’s classmate – but if they did exist, no evidence of these pictures has been uncovered.

Woorrady, a Bruny Island man and later influential negotiator with colonial authorities, told one colonial official that when white men first arrived, they carved the head of a man on a tree, which frightened Aboriginal children. This is an intriguing snippet of information that could relate to earlier tree-markings by colonists, but by itself this evidence tells us little.

The original proclamation board on which the 1866 lithograph was based was the brainchild of the colony’s Surveyor-General George Frankland. In February 1829, Frankland wrote to Lieutenant Governor Arthur suggesting the use of sketches on trees to mimic Aboriginal peoples’ own practice of drawing on and carving trees to communicate. Arthur was the highest British authority in the colony of Van Diemen’s Land; his title reflected the fact that, officially, the only full governor was in New South Wales. Frankland suggested that such picture boards might help Aboriginal Tasmanians to understand “the real wishes of the Government towards them”. Arthur agreed, and had about one hundred wooden boards painted in 1830. Written evidence from the time suggests that different picture boards were also painted, showing scenes such as warriors attacking a settler’s house, and British soldiers firing on warriors, but there are no known surviving copies of these boards.

Proclamations

Before the establishment of elected assemblies, colonial governance often took the form of government by proclamation. Promulgated in archaic language, proclamations can be used to track the key issues of a governor’s reign. George Arthur took office as Lieutenant Governor in May 1824, and in June, he issued a proclamation. Concerned by reports of settlers and convicts firing at, injuring, or killing Aboriginal people, he declared that Aboriginal people “shall be considered as under British Government and Protection”. He warned the colonists that any violation of British law relating to “the Persons or Property of the Natives, shall be visited with the same Punishment as though committed on the Person or Property of any Settler”. The language of Arthur’s written proclamation of 1824 is consistent with the painted boards of 1830, but in between these two, Arthur made other proclamations that departed drastically from the promise of equal legal protection.

Four years later, in April 1828, Arthur issued a very different written proclamation. In it, he outlined the necessity for a “temporary separation” of the Aboriginal and British settler populations in Van Diemen’s Land, “to save the further waste of property and blood”. In his own words: “I do hereby strictly command, and order all Aborigines immediately to retire, and depart from, …[the] settled Districts…on pain of forcible expulsion therefrom, and such consequences as may be necessarily attendant on it”. Any Aboriginal person wishing to remain within the settled districts would require a passport to do so. “Settled districts” were defined as places where land was under cultivation or occupied by a British settler – meaning in practice a large corridor of land between Hobart and Launceston.

India Pattern 'Brown Bess' flintlock musket, British Army, c. 1810. The Brown Bess musket was used by the British Army in Van Diemen's Land.

Arthur declared that these orders were to be communicated to Aboriginal people using “all practicable methods”. By this time, though, few interactions between colonists and traditional-living Aboriginal people occurred unarmed. Aboriginal people were “to be persuaded to retire beyond the prescribed limits”. Those who refused were to be taken prisoner. Armed force was only to be used in self-defence, and was to be “employed with the greatest caution, and forbearance”. Yet the proclamation approved the use of force by colonists when directed by “a Magistrate, Military Officer, or other Person of respectability”. The final proviso in Arthur’s orders was that Aboriginal people were to be allowed to travel through the “settled districts” in order to collect shellfish “according to their custom”, as long as each group leader held “a general passport under my Hand and Seal”. Precisely how the group leaders were to apply for such passports was not spelled out.

With the April 1828 proclamation, huge areas of the island were declared off-limits to Aboriginal people, and Arthur’s assertion that Aboriginal people and British colonists were protected by the same laws was shown to be hollow. It is worth noting that Arthur had never laid eyes on many of the people to whom he addressed his orders, nor did he speak their languages, nor had he made any attempt to understand their laws.

The Black Line

Bands of Aboriginal warriors continued to attack settler properties; more than twenty raids were carried out in October 1828 alone. In November 1828 Arthur declared martial law in the settled districts – again by proclamation. Arthur termed martial law “carrying on military operations against the Natives”, and it was to remain in effect “until the cessation of hostilities”. In just over four years, Arthur had gone from warning settlers that Aboriginal people had the protection of British law, to attempting to remove them from lands considered valuable to the British, to effectively declaring a state of emergency. Writing in 1835, Vandemonian historian Henry Melville saw the declaration of martial law as the government’s response to the “Guerrilla war which had been so harassing and murderous in its effect”.

The 1830 proclamation board dates from this period of martial law and is contemporary to the largest military operation in Australia’s frontier history, the “general movement” as Arthur called it, known to posterity as the “Black Line”. Intent on removing Aboriginal people from lands claimed by colonists, Arthur initiated this infamous operation in October 1830: a line of men, mostly soldiers and convicts, was to march south, sweeping all the Aboriginal people from the settled districts into the Tasman peninsula, south-east of Hobart. In February of that year, the Governor had offered a cash bounty for every Aboriginal person “captured and delivered alive” to a police station. Arthur envisaged that, after the line had succeeded, Aboriginal people would be allowed to live on the peninsula, where they would no longer be a threat to the colony’s sheep flocks or settlers.

Benjamin Duterrau, Manalargerna [a.k.a. Mannalargenna]: A celebrated chieftain of the east coast of V.D. Land (1835, ink on paper, 30 x 24 cm). Courtesy Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania, HA1005

A town meeting in Hobart in September 1830 was called to organise a town guard: civilian volunteers who would conduct the duties of the army garrison while the soldiers were leading the Black Line in the interior. During the meeting, a leading barrister suggested that settlers who killed Aboriginal people during the period of martial law would be guilty of murder. The colony’s Solicitor-General Alfred Stephen responded, stressing that he spoke as a private citizen and not as an office-holder. He argued that the colony owed protection to the mostly convict rural workforce who were the usual victims of Aboriginal attack. This workforce needed to be protected, Stephen told the meeting, and he added, “if you cannot do so without extermination, then I say boldly and broadly exterminate!” Without touching on the legal question of murder, he reiterated: “I am of opinion – capture them if you can, but if you cannot, destroy them”.

To those present, the implication of the Solicitor-General’s startling outburst was that settlers, soldiers, or convicts who killed an Aboriginal person during the Black Line operation would not be prosecuted. Officials were already turning a blind eye to reports of killing. Settler John Batman was the leader of a roving party in the northeast of the island, ostensibly trying to bring traditional-living Aboriginal people into British settlements. Writing to a local police magistrate in 1829, he reported his party’s dawn raid on sleeping Aboriginal people, estimating that ten or more people had been killed in the ambush, and two men who had been badly wounded were taken prisoner. The next day, their wounds prevented them from keeping up with his party; “I was obliged therefore to shoot them”, wrote Batman. He had no fear of legal repercussions.

The scale of the Black Line was enormous. More than two thousand colonists took part, including police, settlers, and a large number of conscripted convicts under the command of British regular soldiers from the garrison. This number represented about 10 per cent of the colonist population. The colony spent more than £30,000 on the operation, about half of the total revenue for that year. After six weeks of marching, the force had captured one boy and one elderly man; two Aboriginal people were reported killed in the operation. Although the operation failed to capture many Aboriginal people, its sheer size demoralised some traditional-living Aboriginal groups outside of what the British called the “settled districts”. In the northeast, one government official recorded that the revered warrior Mannalargenna and his people were in tears the whole day after the Line had been described to them.

"Continued Warfare"

Arthur’s later efforts saw the Aboriginal population of Tasmania removed to Flinders Island in Bass Strait, with devastating effects. Through the late 1830s, the settlements in Bass Strait were subject to despondency and horrific rates of disease. When survivors were allowed to return to the Tasmanian mainland in 1847, only 47 made the journey. The aftermath of war and removal had caused a catastrophic collapse in the Aboriginal population of Tasmania.

In an April 1831 despatch to his superiors in London, Arthur referred to “our continued warfare with these miserable savages”. Such was the bloody backdrop against which the proclamation board was first deployed in late 1829 or early 1830.

Perhaps Arthur understood the visual appeal of a colourful painted proclamation. He was probably also concerned about his own legacy. His proclamation board certainly caught the eyes of those on Tasmania’s exhibition committee in the 1860s, leading to its reprinting in lithographic form. At the Intercolonial Exhibition, it sat amongst photographs, artworks, crafts, natural specimens and geological curios.

Benjamin Duterrau, Aborigines making & straightening spears (1835, etching, 18 x 26 cm). Courtesy Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania, 96179

We can only speculate about why the exhibition committee chose to reprint the board’s motif for the exhibition in 1866. Was it to educate mid-century colonists about the British Empire’s humane mission? Was it intended to support the contemporary idea that Aboriginal people were destined to die out? Was it supposed to suggest that the British had done their best? Some historians have suggested that the incorrect attribution to an earlier governor was designed to make it seem that the British had always tried to do the right thing.

To old colonists such as James Calder, the board brought to mind the bloody conflict that had raged in the late 1820s and early 1830s. Writing in the 1870s, he sardonically recalled that the boards “were to be put in various parts of the bush, to catch the eye of the wandering savage, to whom it was addressed as a sort of preliminary proposal of peace, followed by a feeling intimation that he would be hanged if he did not accept it”. Calder had arrived in the colony in 1829, and he linked the painted boards with Arthur’s written proclamations, which he saw “as so many manifestoes, put forth for after effect chiefly”.

Governor Arthur’s proclamation board is a propaganda piece meant for British eyes. Communicating the promise of legal equality between colonists and Aboriginal people, it was just one aspect of a long-running, sporadic and bloody war fought to determine the question of whose law would prevail in Van Diemen’s Land.