Australian sailors played many important roles in D-Day’s Operation Neptune.

On 5 June 1944, a young Australian naval officer, Sub-Lieutenant Richard Pirrie aboard HMS Invicta, wrote to his family: “Well my dears, the pressure is on now and soon as the weather improves we sail for the greatest event in the history of the world … This is the greatest Armada that ever was formed. A colossal feat of organisation, the product of years of planning and hard work.” The letter was never to be finished. The following morning Pirrie was in command of Landing Craft Support (M) 47 as it approached Juno Beach in the first wave of the D-Day landings.

The success of the Allied Normandy landings on 6 June 1944 could not have been achieved without the Allied navies crossing the English Channel with an amphibious force of substantial might to break in and establish a foothold in Hitler’s fortified “Atlantic Wall”. This assault phase of Operation Overlord (the overall codename for the Allied campaign) was Operation Neptune. The planning for D-Day called for airborne troops to be dropped behind enemy lines to secure the flanks of the five landing beaches. At dawn, naval vessels would begin landing troops on beaches codenamed Utah and Omaha for the American forces, and Gold, Juno and Sword for the British and Canadians. The landings would be preceded by an immense bombardment by Allied air forces, supported by thousands of fighter aircraft. The naval operation, involving more than 6,000 vessels, was the largest armada ever assembled.

Pirrie was one of an estimated 500 Royal Australian Navy (RAN) personnel who were serving in the British fleet on D-Day. Although no ships of the RAN took part in the Allied invasion of France, RAN sailors such a Pirrie served as individuals on attachment with the Royal Navy. Over the course of the war, at least 1,100 members of the RAN served with the Royal Navy. Of the 500 serving in June 1944, more than 400 were officers of the Royal Australian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RANVR). The experiences of these men, serving across a range of duties in ships of all sizes, are not well known.

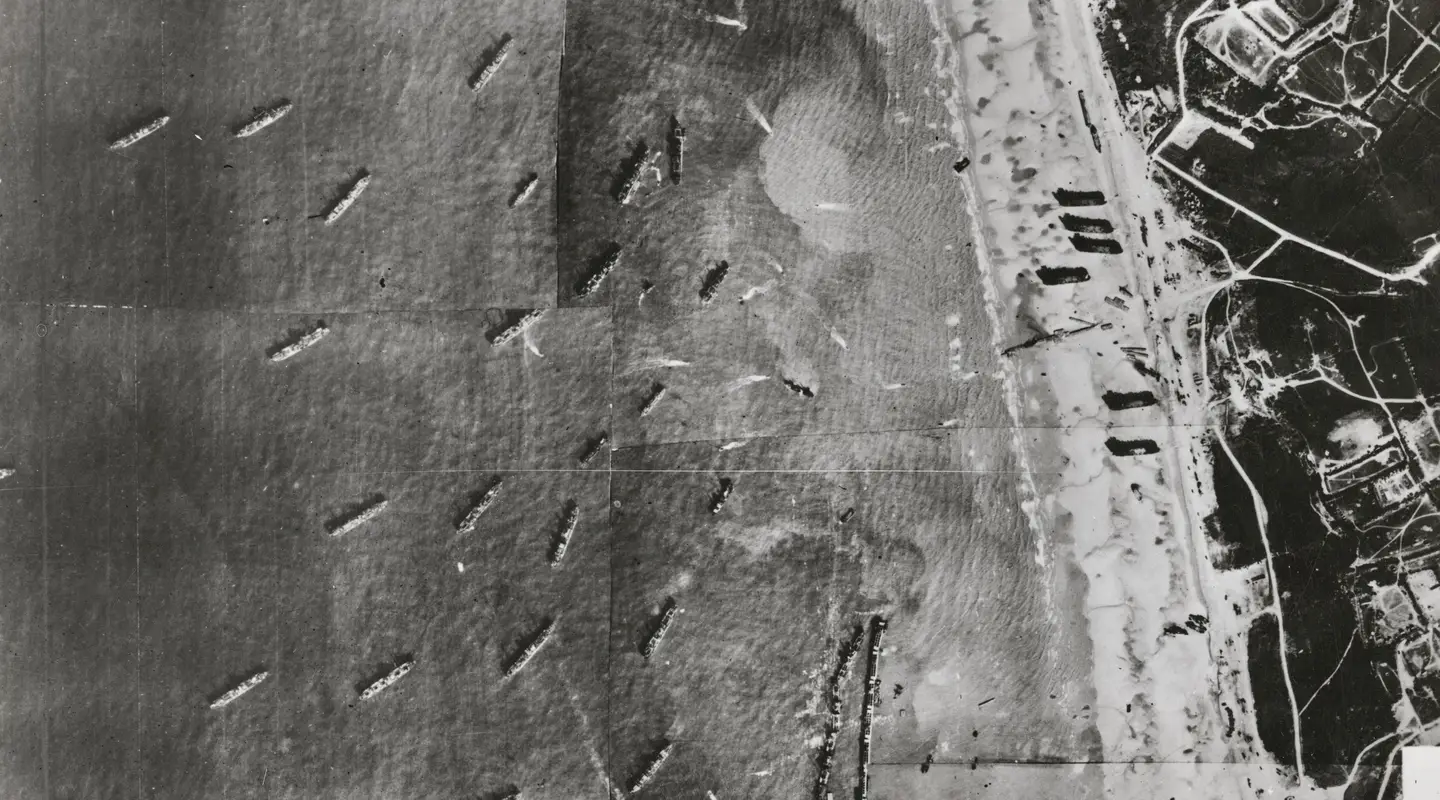

The landing beaches as seen from the air, June 1944. SUK13289

It can be straightforward to tell the story of a single ship, but it is a harder challenge to identify the individual Australians scattered across hundreds of Royal Navy vessels, and to detail their diverse roles. The RAN considered itself part of the King’s Fleet, not a separate entity, so Australian sailors in the Royal Navy had nothing on their uniforms to distinguish them from other Empire naval ratings. On D-Day, Australian officers serving in the fleet were the only members from the Empire with no identifier on their uniform, such as the “New Zealand” shoulder flash worn by their trans-Tasman brothers.

Shortly before D-Day, a major Australian newspaper wrote that these Australians in the forthcoming invasion would be “anonymous fighters”. Many of these men have indeed remained anonymous over the 80 years since D-Day; but new research, cross-checking contemporary newspaper reports with service records and archival material, has assisted in identifying many, returning them from anonymity and bringing to light the breadth of service of Australian sailors on D-Day. That this wider story is not well known is surprising, given that the Normandy invasion was the most important operation in which men of the Royal Australian Navy took part in the Second World War. Here are just a few of their stories.

The vanguard

The first craft to cross the Channel in Operation Neptune were two X-class midget submarines, X20 and X23, with the special mission of marking the approach lanes to the British landing beaches. Commanding X20 was Lieutenant Kenneth Hudspeth, RANVR. By D-Day, Hudspeth was already a decorated veteran, with a Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for his command of the midget submarine X10 in the famous raid on the German battleship Tirpitz in a Norwegian fjord in September 1943.

Lieutenant Kenneth Hudspeth, commander of X20 at Normandy. IWM A 19626.

Hudspeth had previously crossed the channel in command of X20 during Operation Postage Able over four days and nights in January 1944. This was a daring operation to survey and collect geological samples from proposed landing beaches. Hudspeth and his engineer were joined in the submarine by a Combined Operations Pilotage Party comprising a naval officer and two commandos, the “first scouts for the invasion of Europe”. They undertook reconnaissance of the shoreline by periscope during daylight hours, and at night the commandos swam ashore to collect samples from coastline later codenamed Omaha. Described as “quiet, and a thinker” with an “undeniable air of strength” about him, Hudspeth was said to have “handled the craft with a cool dexterity”, and was awarded a bar to his DSC.

For D-Day, X20 returned to Normandy in Operation Gambit. Having left port in England on 2 June, the two X-craft were to lie submerged, anchored off Sword and Juno, to mark the western and eastern limits of those landing beaches. They were to surface at 4.30 am and provide a navigational beacon, using an echo sounder, to guide minesweepers – and then a radar beacon and lights flashing seaward to guide the assault force.

During the day of 4 June X20 was anchored, submerged off Juno Beach, waiting for the message – coded in a BBC broadcast – that the invasion was on. Waiting alone right under the noses of the enemy was an odd sensation. In the cramped conditions the commandos played cards to pass the time. At midnight they surfaced, raised their antenna, and tuned in to the BBC news, waiting for secret codes broadcast to various resistance and special operations units. The messages were meaningless to all except the intended recipient: “For the Padfoot. Unwell in Scarborough” was deflating for X20. D-Day had been postponed for 24 hours: X20 would have to spend another day submerged, anchored to the seafloor.

On the morning of 6 June, X20 surfaced in a growing swell and had rigged up their signals by 5 am. The weather was picking up and waves were crashing over the deck of the small X-craft. Overhead, the drone of the bomber force arriving for the pre-dawn bombardment could be heard. After they had delivered their deadly cargo on the shore, Hudspeth and his crew waited in high expectation, peering into the grey light of dawn for the first sign of landing craft beyond the white caps of rolling waves. Then the salvo of the cruisers and destroyers offshore erupted and soon the shadows of the first landing craft could be seen powering toward them. The crew of X20 waved and cheered them on towards the beach. In all the excitement, Hudspeth fell into the waves for a moment before being washed back aboard with the help of a hoisting hand. The two X-craft had played a significant role on D-Day. They were, said Admiral Sir Philip Vian, the commander of the Eastern Task Force in HMS Scylla, “the vanguard to Overlord”. For his role on D-Day, Hudspeth was awarded a second bar to his DSC. After the war Hudspeth returned to Hobart and his life dedicated to teaching, forever humble about his unique role in the great invasion.

The daring nature of X20’s two missions to Normandy may seem like a Boys’ Own adventure, but the conditions were far from glamorous. Nominally designed for a four-man crew, these missions included an extra man and specialist equipment packed in. Daylight hours (17 in June) were spent submerged within the cramped confines of the X-craft. To ward off exhaustion the crew took Benzedrine tablets, a type of amphetamine. In such confines the air became foul, causing sickness. When they finally surfaced, the fresh air brought on uncontrollable vomiting and splitting headaches. Detection by the enemy would have meant certain death for the crew, and could also have compromised the element of surprise for the whole invasion.

Landing craft and ships carrying British troops head toward Normandy. P05052.002

Crossing the Channel

From the afternoon of 5 June, invasion vessels began departing ports in southern England, converging on an area of sea south of the Isle of Wight unofficially known as Piccadilly Circus. From there the armada of five assault forces, each assigned to a landing beach, headed south toward Normandy. Among the vessels escorting and protecting the convoy were the destroyer HMS Vanquisher, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Frederick Osborne, RANVR, and the frigate HMS Loch Killin, under the command of Lieutenant Commander Stanley Darling, RANVR. During a patrol in July, Darling’s frigate sank two U-boats and assisted in the sinking of two more, for which he was awarded a DSC. Anti-submarine patrols by the Royal Navy and RAF Coastal Command ensured that there was no U-boat interference with the invasion force on D-Day, nor with the supply routes for the duration of the Normandy campaign.

Flotillas of minesweepers cleared a path for the convoys heading toward the five landing beaches. In this force, Australian naval officers commanded two corvettes and a minesweeper. Lieutenant Commander Robert Hart, RANVR, commanded the minesweeper HMS Ilfracombe. It was part of the 16th Minesweeping Flotilla tasked with clearing a channel on the approaches to Utah Beach. Minesweepers in the flotilla came within sight of the Normandy coast at 8.40 pm on the evening of 5 June. It was an eerie feeling for those on board to carry out their vital work during the waning daylight, knowing they were within range of the German coastal batteries. Hart was Mentioned in Despatches (MID) for his service at Normandy.

British or Canadian vehicles head toward the beach at low tide during the invasion. AWM P05052.005

Utah, Omaha and Gold

At the US landing beaches, where the first wave of troops began landing at 6.30 am, Australian sailors served aboard ships in the bombardment force. They included Lieutenant Peter Taylor, RANVR, aboard the cruiser HMS Enterprise at Utah. At Omaha Beach, several Australians served aboard the cruiser HMS Glasgow, including gunnery officer Lieutenant Peter Jellicoe, RAN.

At Gold Beach, the first wave of British troops hit the beach at 7.25 am. In charge of gun turrets bombarding Gold Beach aboard HMS Ajax were Lieutenant Alfred Pearson and Lieutenant Robert Fotheringham, both RANVR. On the frigate HMS Kingsmill, 22-year-old Sub Lieutenant Roy Hall, RANVR, was commanding A and B gun turrets. He wrote in his diary:

“I glanced around the lads on the guns and wondered if their knees tended to knock with the cold and tension as mine did. We conversed in hushed whispers and speculated when the Germans would suddenly wake up and all hell would be let loose. Still nothing happens and the day growing lighter every minute. We can now see the mass of ships which stretch from the horizon to seaward and up and down the coast which is now a blurred line in the murky morning light … Then a two-hour bombardment commenced from a total of 90 battleships, cruisers, destroyers and other gunships on assigned targets ashore … great clouds of acrid smelling brown cordite smoke drifted across the anchorage. One huge cloud of smoke and dust obscured the whole coastline, which was enveloped in a massive convulsion of explosions. We wondered how anything could possibly survive.”

Commanding a flotilla of Landing Craft Assault (LCA) in the first wave at Gold Beach was Sub Lieutenant Dean Mugg (known as Murray postwar), RAN. Although the sea was rough, the journey to shore, with a tailwind, went relatively smoothly. Mugg was able to lead his flotilla in and land at the correct spot. However, after taking one hour to reach shore, it was a much more difficult two hours zig-zagging into a strong headwind to return to the Landing Ship Infantry Empire Halberd to collect more troops. By this stage the sea was becoming increasingly rough. In the heavy swell, Mugg’s LCA was constantly lifted and dropped 10 feet (three metres) as they loaded men. “We had the whole day the wind and the waves,” he later recalled, “but that’s the sailor’s life.”

Commander Dean Robertson Murray reflects on the landing at Normandy

It was about four days before the event that we were briefed.

We were told where we were going, at what time, and there were a good deal of diagrams, photographs of the landing beach. These had been taken from submarines, aircraft, and even some from surface craft, so that we were able to pinpoint the point of our landing.

Now, the landing we were directed to was the easternmost landing on the Normandy stretch. That whole stretch of Normandy covered about 50 miles. The Americans on the western side, and British and Canadian forces on the eastern side.

There was a great deal of secrecy about it, because they didn't want the Germans to know where it was going to happen, and in fact a lot of effort went into disguising the fact that it would be the Normandy beaches.

Unfortunately, the weather was very, very bad, and although the 5th of June had been put down as the landing day, that had to be postponed. It could only be postponed for 24 hours, because there was only a four-day period when the landing could take place.

When we landed at Gold Beach, there were of course 28 of our landing craft, but there were three other ships in the near vicinity, each with a 28 landing craft, and these were interspersed with destroyers which were doing the bombarding.

The whole sea was crowded with ships. There were ships just everywhere.

[partial] oral recording of Dean Robertson Murray RAN, 28 January 2004 AWM S03242

A Landing Craft Tank heads to shore as a US battleship bombards the shore. P02018.287

Less fortunate in the rough conditions at Gold was LCA (Hedgerow) 1106, commanded by Sub-Lieutenant Bruce Ashton, RANVR. After arriving in Britain, Ashton had trained at HMS Osprey, an anti-submarine training establishment, in the use of the newly developed and lethal Hedgehog, which fired a cluster of 24 to 30 mortars against a submarine. From August 1941 to March 1942 Ashton served on Atlantic convoy duty aboard the destroyer HMS Montgomery, newly equipped with Hedgehog. He then trained with Combined Operations to bring his knowledge of Hedgehog to amphibious operations, where it would be used more like a conventional mortar to clear a 100-yard-wide pathway through mines and beach obstacles ahead of the landing infantry. Approaching Gold Beach on D-Day, and yet to fire its mortars, LCA (HR) 1106 was accidentally rammed by an out-of-control landing craft and capsized, killing Ashton and members of his crew. His body was later recovered and buried in the Bayeux War Cemetery.

"One huge cloud of smoke and dust obscured the whole coastline, which was enveloped in a massive convulsion of explosions. We wondered how anything could possibly survive."

Sub Lieutenant Roy Hall, RANVR

Juno Beach

Richard Pirrie was in the first wave of landing craft heading toward Juno Beach. Pirrie, a promising sportsman, had played three games on the wing for the Hawthorn Football Club. Called “Digger” by his British colleagues, Pirrie had extensive service aboard destroyers on convoy duties to places such as the Soviet Union, Panama, Iceland and Malta before he joined Combined Operations. Like many of the Australians serving aboard landing craft, before the Normandy landings Pirrie had commanded landing craft during the invasions of Sicily and Italy in 1943.

On 6 June 1944, his 24th birthday, Pirrie was tasked with piloting LCS (M) 47 close to the beach in full view of the enemy. From the craft, a naval artillery observer he was ferrying could direct naval gunfire onto the German defences. An Australian correspondent for Sydney’s Daily Mirror reported Pirrie’s departure from the landing ship HMS Invicta:

“Few could have played a braver or cooler part than ‘Digger’ … Dick’s close-cropped black beard and satanic grin were widely known among the little ships of the Royal Navy. He was typical of many RAN men over this side of the Channel today … Before leaving, ‘Digger’ came up on the bridge and swore blisteringly at the weather, which was making the sea choppy, but when I leaned from the bridge and waved him off, he grinned and cocked an impudent beard at the enemy.”

As it approached the shore, LCS (M) 47 simultaneously struck a mine and was hit by an enemy shell, killing Pirrie. For his “gallantry, leadership and determination”, Pirrie was awarded a posthumous MID.

Bodies and beached landing craft litter Juno Beach on D-Day. IWM MH 2329

Lieutenant Commander Frank Appleton, RANVR, was in command of the 31st Landing Craft Tank Flotilla, transporting Canadian troops to Juno Beach. These vessels had Sherman tanks lashed aboard, whose guns were to be used to support the bombardment before going ashore. He later reflected on his landing at Juno:

“It was like something from The Inferno. There were vivid flashes as the guns went off, and increasingly so from the shore as the Germans got some counter-fire into action. The rocket ships were firing salvo after salvo – thousands of things – and an RAF fighter pilot who was helping our air escort came down a bit too low just as one launch went up. It was like a matchbox catching fire. It was awful.”

Lieutenant Commander Frank Appleton, RANVR

Lieutenant Commander George Dixon. A young soldier on Gallipoli in 1915, he later commanded an LST on D-Day. AWM045310

Others to command LCT flotillas were Lieutenant Commander Arnold Anderson, Lieutenant Alfred Weston and Lieutenant Commander Stewart Browne (all RANVR). Weston and Browne were awarded MIDs for Normandy. Commanding his flotilla from LCT 1048, Browne’s MID was his second, to go with the one he was awarded for Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942.

Also at Juno Beach was Lieutenant Commander George Dixon, RANVR. Commanding Landing Ship Tank 409, Dixon had the distinction of being involved in three of the major amphibious operations of the twentieth century. Serving with the 12th Battalion, AIF, he was among the first to land at Anzac Cove on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. Just 15 years old at the time, he had enlisted underage, claiming to be 19 and a half. Not long after landing on Gallipoli he received multiple gunshot wounds to the forearm and foot, and was sent home to Australia and discharged. At the outbreak of the Second World War, Dixon again enlisted for service, this time in the RANVR. By D-Day he was already a decorated veteran, with a DSC for Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, in 1943. After the war, Dixon continued to serve in the navy and notably commanded an LST on two Antarctic expeditions. Mount Dixon on Heard Island in the Southern Ocean is named in his honour.

Sword Beach

At Sword Beach, on the eastern flank of the Allied lodgement, British troops had begun landing at 7.25 am. Australians serving aboard cruisers involved in the bombardment included Sub Lieutenant John Dawson, the gunnery officer in HMS Mauritius, who was awarded an MID; Lieutenant Dacre Smyth, the torpedo officer in HMS Danae; and Sub Lieutenant Ian Howard, serving in the destroyer HMS Impulsive. Like many watching aboard the ships offshore, Howard wrote in a letter home to his parents that his thoughts were ultimately with “those boys ashore [who] are certainly going through hell.”

Waiting offshore at Sword Beach was Sub Lieutenant Theo Arthurs in LST 420. His ship spent much of 6 June anchored just off the landing beach; on board, the sappers of the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers beach recovery unit were scheduled to land on D-Day plus 1. During the morning of the landing, LST 420 came under fire from German defences. Shrapnel from one shell wounded a Royal Marine manning an Oerlikon gun. The waterspouts erupting around LST 420 quickly gained the attention of an alert Royal Navy destroyer, which powered past LST 420. The destroyer’s guns zeroed in on a fortified farmhouse in which the offending German gun was concealed and soon reduced it to rubble.

Protecting the fleet

Across the landing beaches, a number of Australians commanded motor launches and Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs). They included Sub Lieutenant John Ferguson, RANVR, who commanded a flotilla of MTBs from MTB 209 and was awarded a DSC for his service at Normandy. The main task of the MTBs was to protect the flanks of the convoy from German attack, and on several occasions during the campaign they engaged with German torpedo boats – called E-boats by the British – which were a constant threat. The Kriegsmarine also adopted the tactic of deploying divers on Neger torpedoes, a kind of one-man midget submarine often called a human torpedo.

ften called a human torpedo. One of the Australian sailors killed during the Normandy operations was lost in such an attack. Surgeon Lieutenant Derek McKenzie, RANR, was killed while serving in the destroyer HMS Quorn. Assigned to escorting convoys across the channel, on 3 August 1944 Quorn came under attack by a force of E-boats and human torpedoes. Quorn was struck by a torpedo, broke in two, and sank rapidly; McKenzie was one of the four officers and 126 ratings killed.

Others involved in escorting convoys and guarding the supply lines across the Channel were Lieutenant William Wood, RANVR, in the frigate HMS Holmes (awarded an MID) and Lieutenant Hugh McDonald, RANVR, in the destroyer HMS Eskimo. For several hours on 24 June 1944 Eskimo, alongside the Royal Canadian Navy destroyer HMCS Haida, successfully hunted U-971. Several decorations were awarded to the crews of Haida and Eskimo for this action, including a DSC to McDonald for his “bravery, skill and devotion against U-boats in HMS Eskimo”.

Lieutenant (later Lieutenant Commander) Leon Goldsworthy rendered safe enemy mines in Normandy. AWM081383

On land, the battle of Normandy raged until the Allies broke out of their foothold. A crucial element of the planning of Overlord was the capture of a deep-water port as soon as possible after D-Day. The fortified port city of Cherbourg, on the Cotentin Peninsula, was strategically vital for both sides, and the Germans were determined to prevent its capture. American troops began their assault on the city on 22 June. It would take a week of fierce fighting before the German garrison surrendered. During the battle, Allied ships offshore bombarded fortified positions, and navy mine-clearance divers, including Lieutenant Leon Goldsworthy, RANVR, went to work rendering the mined and booby-trapped harbour safe for Allied vessels. Under enemy fire, Goldsworthy rendered the first German K-mine safe. At a depth of 50 feet (15 metres), the mine was embedded in a block of concrete on a steel tripod. Goldsworthy felt it was a “rush job”, such was the urgency to clear the harbour; but succeed he did. As well as being shot at, there were minesweepers working nearby, and divers knew that they would be killed if a mine exploded within a mile of where they were operating. Earlier in the Normandy campaign, Goldsworthy had rendered several mines safe at the British landing beaches. For his work at Cherbourg, Goldsworthy was awarded a DSC to go with the George Cross, George Medal, and MID he had previously been awarded.

After reading a report on the work of Goldsworthy’s team, Sir Winston Churchill wrote to the First Lord of the Admiralty that he had “been much impressed”, and that the “work f these Officers and Ratings, and the cold-blooded heroism with which they performed it, have been of the highest quality, and have been the cause of saving many lives and homes.” Like Hudspeth, and many of their generation, Goldsworthy was said to be reticent about the exploits that had made him Australia’s most decorated naval officer of the war.

The job done

Operation Neptune officially ceased on 30 June 1944. By this date, more than 850,000 troops, almost 15,000 vehicles, and over 570,000 tons of supplies had been landed, although the naval forces continued to land troops and supplies after this date. The Allied planning for the success of Neptune had called for every soldier, sailor and airman to carry out a specific task. The success of the landings would not have been possible without the skill and professionalism of the naval officers and ratings, including those members of the Royal Australian Navy in their diverse roles. Their contributions to D-Day, once described as “anonymous”, deserve to be known.