Australians in the Imperial Camel Corps.

So wrote Commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, General Edmund Allenby, to the Commander of the Imperial Camel Corps (ICC), General Clement Leslie Smith when the Brigade was disbanded in late 1918. Almost two decades later, one of the Brigade’s staff captains, W.T. Bichan, believed that it would have been more accurate to say that they have all echoed “to the shuffling of the Brigade”.

The ICC was formed in January 1916 to join the Western Frontier Force fighting the Senussi people of the Libyan desert as part of the broader campaign against the Ottoman Empire. When the cameleers (or cameliers) arrived in March 1916, there was very little fighting against the Senussi left to be done, so their skills were used to patrol the desert. It was conditions like these that the Camel Corps had been designed for. Horses proved unsuitable in the sandy and arid climate, as they needed watering far too frequently, so the camel was determined to be the more effective mount in Egypt. Camels could go five days without water and could carry greater loads of rations and equipment, enabling the Camel Corps to conduct five-day patrols and cover a far greater area than would be possible on horseback.

Initially made up of four companies of mounted infantrymen, the cameleers were soldiers who had either volunteered or been selected by their previous unit commanders for transfer. They came from across the Australian Infantry Brigades and the Light Horse Regiments that had been evacuated from Gallipoli in December 1915. From the time the first four Australian companies were formed, it was said that officers from outside the ICC had taken this as an opportunity to discard the riff-raff from their own battalions. But this was not the case. Many of the early cameleers were volunteers who could boast general experience with animals or stock, and some could even count camel experience with the British in Sudan. When Lance Corporal Bendyshe of the 26th Battalion applied for transfer to the ICC on the grounds of his pre-war experience with camels in Western Australia, his commanding officer supported his application saying, “This is an exceptionally good and reliable man.” Bendyshe was among a number of highly trained and experienced soldiers who volunteered for the Camel Corps: not exactly the riff-raff they were made out to be. While these recruits challenge the dominant perception of the Camel Corps’ formation, the Corps did receive its share of rogues in its infancy. On 2 February 1916, the Commandant of the Camel Corps informed the commanding officer of the 4th Brigade that Privates O’Shea, Ottaway, and Murdoch were being returned to their original units for “disciplinary reasons” less than a month after they had arrived. The circumstances of their “misconduct” were not revealed, and replacements were requested.

Australians of the Imperial Camel Corps on parade near Rafa, 26 January 1918. Photographer Frank Hurley.

Settling in

Those transfers who managed to avoid disciplinary action were deployed primarily as patrolling units in the desert around Sollum, along the Egyptian/Libyan border. Unit diaries for the ICC paint a picture of this monotonous time, perfectly articulated by Private Charles Banwell Dodd in his diaries: “nothing to report”. Captain George F. Langley wrote in a letter home in May 1916 that “when we saw the battalions on the move for France, we felt just a little down-hearted.” Some soldiers reacted to the boredom in more radical ways. In June 1916, fifteen Australian soldiers were returned to the training battalions in Tel-El-Kebir as “undesirables”. The missive stated that “their object apparently has been to misbehave themselves in such a way as to get removed from the Corps and thus be sent to France.”

This willingness to act out, in the hope of being sent to the Western Front, perhaps explains some of the early misbehaviour of certain members of the supposedly troublesome Camel Corps. In other cases, as was the reality across the AIF, some soldiers simply misbehaved. Others instead felt a longing for the life of the Light Horseman and all the attached romance and heraldry. A poem written by Major Oliver Hogue under his pen name, Trooper Bluegum, titled “The Camelier’s Lament” bemoaned that

The monotony of an early cameleer’s life was a far cry from the imagined action of the Light Horse. Midway through 1916, the British commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, Sir Archibald Murray, decided to expand the ICC and specifically requested more Australian troops fill the ranks. This might seem at odds with the reputation the cameleers had created for themselves, but is open recognition of the skill these supposedly rough Australian soldiers so clearly possessed. He wrote that the Australians had “no idea of ordinary decency or self-control” but were “from a physical point of view a magnificent body of men”. The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade (ICCB) was formed on 19 December 1916. At full strength, the brigade boasted approximately 4,150 men and 4,800 camels. The Brigade also included the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery. This created something of a melting pot of identities: men from across Britain and the Australasian dominions – including 13 Indigenous Australians – served alongside Muslim and Sikh men from the Battery. Australian soldiers in the ICCB always made up the majority of troops in the corps, making it a truly unique Brigade within the ranks of the British Forces.

Members of the Camel Corps in their first major action helped to capture the Turkish outpost at Magdhaba on 23 December 1916. Artist: Septimus H. Power, oil on canvas

Into battle

The first battle in which the Brigade saw action was the battle of Magdhaba on 23 December 1916. After a brutal night march, the ICCB attached to the Anzac Mounted Division were ordered by Major General Sir Harry Chauvel to begin what needed to be a swift and decisive assault. The Cameleers of the 1st and 3rd Battalions rode close to the town, then dismounted and advanced directly on the Ottoman-held town, rapidly capturing their objective. Their success turned the tide of the battle, convincing Chauvel to withdraw orders to retreat. Gullet in the Official History wrote that “the significance of the achievement of … the Camels was immediately demonstrated.” The battle gave the ICCB a new reputation: that of competent and skilful soldiers. Chauvel later inspected the Brigade and “complimented it on its success at Magdhaba”. In their first combat as a brigade, the Cameleers had, according to the Tweed Daily on 1 January 1917, “proved the sterling value of the Camel Corps”.

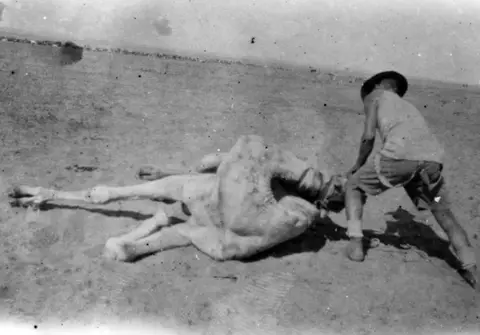

When the Brigade was not fighting or patrolling, they were taking care of their nearly 5,000 camels. They required regular grooming and mange dressing for itchy skin, as well as tick removal and treatment for wounds sustained in combat or from their heavy loads. For the men, camel itch came from contact between human skin and the camel’s hair; it was an ever-present maintenance issue and an extremely unpleasant experience. But an individual camel’s temperament was perhaps the defining factor in a cameleer’s experience. Some were known to be aggressive or majnoon, an Arabic word for crazy; and there were rare recorded instances of soldiers being killed by a camel. Writing for the Corps’ newsletter in July 1917, Reid described the camel as an “unwieldy creature that is calculated to act detrimentally towards that close feeling of intimacy which might be desired between a camel and his rider.” Even when some camels were even-tempered, they were a far cry from the horses left behind by some of the men from the Light Horse, and there were substantial currents of negative feeling toward their mounts recorded in 1916 and 1917.

Members of the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery with their camels, loaded with Vickers 2.75 inch MK 1 Mountain Guns and other equipment. Photographer Frank Hurley, February 1918.

In March 1917, the ICCB took part in the unsuccessful first battle of Gaza but saw little action and suffered minimal casualties. The allied forces regrouped and on 17 April 1917 began their second assault on Gaza, in which the ICCB took on a far greater and more costly role. With all the British cameleers in reserve, the brigade was represented entirely by Anzac troops. Their objective was a hill later dubbed the “Tank Redoubt” after the British tank nicknamed “Nutty” that led the cameleers across the field. Rather than providing cover for the men behind it, according to Captain Bichan, the tank “drew artillery fire all the way and any troops bunched near it were slaughtered right away”; the tank was destroyed when it reached the redoubt. Fighting on despite extreme casualty levels, the Australian Cameleers succeeded in taking the redoubt. They were the only allied unit to achieve their objective. This position was held with heavy losses, and with no success at any other part of the line, the few surviving Cameleers were forced to evacuate.

By dusk on the 17th, the brigade had suffered 345 casualties and 176 camel casualties. Bichan described it as “a heart-breaking day” but simultaneously commended the Brigade for the “wonderful courage and bravery [that] had been displayed during the advance”. The second battle of Gaza represented the heaviest loss for the ICCB of their entire campaign.

Morale

After two defeats at Gaza, morale was at an all-time low across the entire Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF). In 1917 the cameleers began publishing newsletters of the Imperial Camel Corps, Barrak, and its Field Ambulance, Cacolet. These newsletters adopted the distinctly humorous Anzac tone and undoubtedly brought much enjoyment to their thousands of readers, both in Egypt and home in Australia, asking profound questions such as “What is the difference between ‘Leave, dental’ and ‘Leave, absent without’?”. In Barrak’s first issue, Reid placed a ‘for sale’ advertisement for a “modern steam camel” which he claimed boasted a “pneumatic hump” and an “adjustable bladder”.

By the end of his service with the Imperial Camel Corps, Captain Oliver Hogue (centre) had come to at least tolerate his camel.

A regular instalment in the newsletters was the Brigade sports news. The first edition of Barrak reported a two-day sporting contest presided over by the officers, who judged competitors in events like the Camel Scurry, Camel Wrestling, Tug of War, and Musical Chairs on Camels. In July 1917 Langley wrote home that the men were “delighted” with the displays of athleticism and that “it brought officers of different battalions closer together – and men of different companies came to know others as battalion comrades.” These events were held on many occasions throughout 1917 and ’18, and Souvenir Programmes recorded the names of competing camels with their riders. Much can be gleaned from these names about an individual soldier’s personal affection for his camel. The temperament of Smiler or Starlight was likely vastly different from that of Cyanide. However, Cyanide’s silver medal in the February 1918 Camel Trot undoubtedly brought some measure of glory to the trooper on his back, or at least the 100 piastres in prize money surely would have.

Amman

After spending Christmas near Jerusalem, the ICCB returned to action as the EEF set its sights on Amman. But the rocky and treacherous terrain of the Jordan Valley and southern Palestine proved very difficult for the camels. According to Hogue, “never will the Cameleers forget that night journey over slippery goat tracks to Es Salt.” He described how “camels would collapse, bogged and helpless, and some toppled over the precipice.” The attributes that made the camels preferable to horses in the Sinai were now actively endangering the men of the brigade. With attempts to reach Amman ending in failure, the EEF retreated and regrouped in Palestine; it was here that the brigade would fight in their final action.

The relationship between rider and camel was often fraught. Here an Australian cameleer overpowers an uncooperative camel.

Ottoman forces launched a counter-attack in the Jordan Valley on 11 April 1918. The heaviest blow fell on the 1st Battalion at Musallabeh. This rocky outcrop provided minimal cover from the heavy shelling, which was followed by vastly superior numbers of Ottoman troops who rushed the hill. Three hours of intricate and close-quarters combat ensued, during which the cameleers exhausted their ammunition and in desperation began to heave boulders down the hill onto the enemy. Gullet commented in the Official History that “although sorely pressed, the Camels never lost control of a critical situation.” Reinforcements eventually arrived and secured the Australian position. By the morning of the 12th, approximately 60 of the 100 men at the garrison the previous day were casualties. The Ottoman dead numbered close to 170. The Australian soldiers of the 1st Battalion distinguished themselves in their last battle, the greatest single success of their entire campaign. General Allenby declared that Musallabeh should forever be known as “The Camel’s Hump”.

It was not long until the order came from the Egyptian Expeditionary Force that the Corps was to be disbanded, with troops returned to their parent units or formed into Light Horse Regiments for the big push north into Syria for Damascus and Aleppo. In June 1918, the Australian and New Zealand Battalions of the Imperial Camel Corps were officially disbanded. The Australian troops formed the 14th and 15th Light Horse Regiments, which became part of the 5th Light Horse Brigade. The Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery were also part of this new Brigade; the Camel Field Ambulance gave up their camels for horses but continued their work with their fellow ex-cameleers. Only the 2nd British Battalion remained mounted on camels, as they were sent back into the desert to assist T.E. Lawrence, later famed as Lawrence of Arabia, with the Arab Revolt.

Major Oliver Hogue, of ‘Trooper Bluegum’ fame, initially loathed camels, but in 1918 wrote Farewell to my steed as an apology.

In July 1918, the 1st Battalion held a mock funeral to commemorate the life of the Camel Corps. They wrapped a camel’s saddle in the Union Jack and after holding a full military funeral, they buried the saddle outside their camp. The padre conducting the burial service ended with these words:

I invite you all to look for the last time on this emblem of the departing Camel Corps … upon this instrument both of comfort and torture. We commit its saddle to the ground … in sure and certain hope that it will never rise into being again while this war lasts.

There are many parallels to be drawn between the Cameleer and his mount. Just as the camel was a cantankerous and at times difficult beast to manage, it proved its worth in the fulfilment of its duty, even if perhaps in a rougher, coarser way than would be expected of a horse. While the stigma of being a rough band of men pulled from the dregs of their former battalions plagued the ICCB throughout its lifetime, the Australian Cameleers proved themselves time and again to be skilled and dependable soldiers who embraced their reputation and formed a vital component of the AIF’s Middle Eastern campaign.

In August 1918, following the disbandment of the Imperial Camel Corps, Hogue, who had once described the camel as one of the “vilest, stupidest, craziest beasts that ever cumbered the earth”, wrote a poem called Farewell To My Steed. It is something of an apology to his camel, and reflects the ways the cameleers’ sentiments had changed over their time together:

It was then my errant fancy lightly turned to thoughts of verse,

And I libelled you, old Hoosta, in a wild iambic curse.

I know you now for better; but for you, I might be dead.

So I recant, old Hoosta, I take back all I said.