After the First World War, Indigenous soldiers struggled to gain rights and recognition as Australian citizens.

In the early twentieth century, Indigenous Australians had few rights, often lived in poor conditions and faced ongoing restrictive oversight from Aboriginal Protection boards and mission overseers. When war broke out in August 1914, Indigenous Australian men were barred from volunteering for the newly formed Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Those who did attempt to enlist faced the possibility of rejection and discharge on the basis of their race, sometimes months after they had first signed their attestation papers. Policies were unevenly and sporadically upheld, varying between recruiting locations, states and medical officers. Despite these restrictions, many Indigenous Australian men wanted to serve their country, and in some cases went to great efforts to be able to do so. Some men changed their name, place of birth and nationality to be allowed to enlist, and others volunteered multiple times before finally being accepted.

The willingness of Indigenous Australian men to serve a country that often denied them the rights and privileges freely granted to other Australians did not go unnoticed back home. While some responded with derision and confusion to the support being shown by Indigenous Australian individuals and communities for the war effort, others saw an opportunity. Beginning during the war and carrying on over the next two decades, Indigenous Australian activists and their supporters realised the potential of using wartime service to agitate for greater rights in Australia. They incorporated stories of service and sacrifice into their petitions and speeches, relying on letter-writing to spread their message across newspapers and into the offices of government officials.

Private Victor Nelson of 2/3 Pioneer Battalion at Tarakan, Borneo, 1945. Photograph Ross Rainford, AWM089736

By 1918 an idea was well-established in Australia: that military service was an act of sacrifice for the nation, meaning that returned soldiers should be able to claim additional citizenship entitlements. Veterans returning from the First World War used this understanding to argue for pensions, employment training, medical and hospital treatment, educational allowances, and land and home loan packages. These arguments were put forward by veterans across the globe during the 1920s and 1930s, but were particularly successful in Australia due to the political power of the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA) and the relative economic prosperity of Australia. Throughout history, similar arguments had been put forward after wars by marginalised groups seeking to gain equality by virtue of their voluntary military service in times of need. These arguments were again used after the First World War by colonised populations across the Indian subcontinent and Africa, by African Americans in the United States, and by Indigenous peoples across the British settler dominions.

In service

Drawing on these global and home-grown trends in returned servicemen’s rhetoric, Indigenous Australian protestors embraced the argument of military service in their struggle for greater rights after the First World War. During this period, Indigenous Australian activism began to organise and consolidate. Brought together under influential leaders such as William Cooper, William Ferguson, Jack Kinchela, Fred Maynard, Douglas Nicholls and Jack Patten, Indigenous Australians across Australia formed activist organisations, engaged in letter-writing campaigns, and began to adopt the language of protest, citizenship and legal rights. Engaging with and mirroring similar civil rights movements globally, these activists pushed for concrete and meaningful changes to the way Indigenous Australians were treated and viewed in Australia, both socially and under state and federal laws.

Part of the increased push in the 1930s could be attributed to the measure of equality experienced by Indigenous Australian servicemen during the war. Once men joined the AIF, there were no formal discriminatory policies in place. Whether or not this was because their presence had been unanticipated, the absence of such policies had an immediate and noticeable impact. Indigenous Australian men received the same pay as non-Indigenous men of equal rank. They had the same accommodation and food, both in training camps in Australia and serving overseas. Despite debate in Australia over their ability to serve effectively, Indigenous Australian servicemen were employed under the same conditions as other members of the forces; they were instructed to carry out the same tasks and were eligible for the same awards and promotions. At least eight Indigenous Australian soldiers were awarded a Military Medal or Distinguished Conduct Medal during the First World War; current research suggests 77 men held the ranks of non-commissioned officers, and five were either Warrant Officers or commissioned officers.

Private Alfred Jackson Coombs, one of over 1,000 Indigenous men to serve during the First World War, served with the 59th Battalion on the Western Front before being captured by the Germans. P03906.001

For the most part, men on active service overseas were treated equally by their fellow soldiers and were regarded positively by their comrades and commanding officers. They joined other Australians on leave in England and in Egyptian and French villages behind the lines, where they visited pubs and theatres without provoking concern.

Soldiers writing home spoke of their “good treatment” while on leave, and the joy of passing the time with “mates” from their battalion. They fondly recalled sharing beers with other Australians and enjoying the friendly attention of locals wherever they went.

Even when men did face discrimination as a result of their race from other members of the AIF, it was often short-lived and quickly shot down by other servicemen. One Aboriginal soldier remembered how a machine-gunner from the 3rd Division had expressed annoyance at having to eat alongside him at dinner one night, only for the machine-gunner to receive threats “of a bloody smack on the snout” from other members of the battalion for his attitude. The soldier recalled that “the next day he came looking for me, and we sat down to eat together. He turned out to be my best mate.” Friendships forged between Indigenous Australian servicemen and other members of the AIF often continued after the war, their shared experiences more powerful than the discriminatory policies and racist attitudes at home.

After the war

As Indigenous Australian servicemen trickled home from the war – either discharged early after wounding or as part of the mass demobilisation at the end of the conflict – they found themselves returning to a situation largely unchanged from before the war. Returning to civilian life meant a return to a life of extreme discrimination, dispossession and subjection to control for many. Men were once again restricted in where they could live and visit, and who they could socialise with. Many returned to the supervision of missions and stations, where their occupation, marriages and free time were all carefully managed. Some men returned home to find that their children had been taken away while they had been overseas fighting in the war; these children were now wards of the state in the early stage of what would become the Stolen Generations. Communities faced the closure of reserves and the merging of missions, often forcing entire family groups off their traditional land and threatening to separate extended families.

There was initially some uncertainty over whether war service would entitle Indigenous Australian veterans to some freedom from the powers of the various Aboriginal Protection Acts in operation across Australia. In 1919, the Department of Repatriation for New South Wales asked the Ministry of Defence whether Aboriginal men who had served with the AIF were still considered under the restrictions of the state’s Aborigines Act. The response was unambiguous: “The fact of an aboriginal having served with the AIF does not remove him from the care or supervision exercisable by the Board.” The freedom experienced by servicemen during their time outside Australia was rapidly replaced with restriction and control upon their return home.

The Australian Aboriginal League was formed by William Cooper in Melbourne in 1932 to protest the conditions under which Aboriginal people were forced to live. P01248.001

One of the only options available to Indigenous Australians seeking to live life beyond the control of the Board was to apply for an exemption certificate. These certificates promised access to the benefits of Australian citizenship that “Aboriginal” status precluded them from, including access to education, health services, housing and employment. In exchange, however, exempted individuals were required to give up their language, identity and ties to their family. Eligibility for exemption was judged by a tribunal, based on the person’s level of assimilation into white society, their education and their value as a potential employee. War service itself did not automatically warrant the issue of an exemption certificate, despite the fact it ostensibly proved the engagement of the applicant with white society and often provided valuable character references. Very few Indigenous Australian veterans applied for an exemption certificate after the war, and even fewer were granted one.

Reactions

The discrimination and prejudice facing Indigenous Australian veterans and their communities on their return to Australia caused a great deal of resentment for many men. Private Herbert Milera, from Raukkan in South Australia, on returning home reflected, “While I was in the military uniform, I was granted all the privileges one could think of, even going to a hotel and having a glass of beer. Now it is all over … I am practically No-Body.” In 1935 a man from Cherbourg in Queensland wrote, “I always thought that fighting for our King and country would make me a naturalised British subject and a man with freedom in the country but … they place me under the Act and put me on a settlement like a dog.”

The ongoing inequality facing Indigenous Australian veterans and their communities, exacerbated and highlighted by their recent experience of equality, provided a catalyst for action and activism. By proving their loyalty to king and country through military service – that is, upholding their side of the citizenship bargain – Indigenous Australian activists argued that they deserved to be considered on an equal footing with other Australians and to be extended the same rights as their non-Indigenous counterparts.

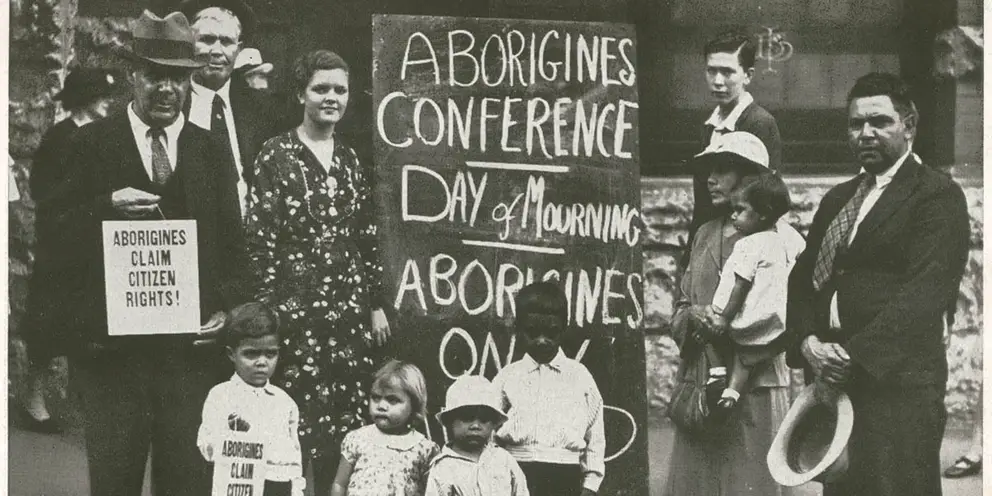

William Ferguson (left) and Jack Patten (right) at the Day of Mourning conference, 26 January 1938. Photograph: Russell Clark. Q 059/9 Courtesy of State Library New South Wales.

Indigenous Australian activism during the interwar period addressed a number of interlinked concerns, including access to education, freedom to visit pubs and hotels, the protection of Aboriginal land and reserves, and the lack of respect shown to Indigenous Australians by the wider Australian public. In 1918 Noongar man John Kickett wrote to his local member of parliament regarding Aboriginal children not being allowed to attend public schools. In his letter, Kickett argued that “as my people are Fighting for our King and Country, Sir, I think they should have the liberty of going to any State school.” In 1924, frustration with South Australia’s restrictive liquor licensing laws, which prohibited Indigenous Australian people from drinking, spilled over into the Advertiser. An unnamed Aboriginal man complained in a letter to the paper: “While we wore the King’s uniform, on active service abroad, we were allowed to indulge in as much liquor as it was possible for us to consume. Since our return to the land of our birth, and the good old uniform is laid aside, we are again placed under the ‘Blackfellows Act’. Where is the justice of this?” Condemning the mistreatment of Aboriginal Australians in South Australia, Private John Eustace Bews argued that “there have been many Aborigines who have nobly responded to our Empire’s ‘call to arms’ … we feel humiliated to know that we are still looked upon as a servile cringing race.”

The death of Indigenous Australian servicemen was often explicitly mentioned as part of individuals’ attempts to persuade their audiences that Indigenous Australians should be granted the rights or recognition they were campaigning for. A Western Australian Aboriginal man wrote to the Sunday Times in 1921, explaining, “Some of our number took part in the great war and made the supreme sacrifice, while others have returned to find that they are no nearer getting a fair deal.” Protesting the planned closure of the Warangesda Aboriginal Reserve in 1926, Jimmy Murray wrote, “During the Great War a number of our boys from Warangesda went overseas … and some did not come back – a nephew of mine amongst them. Do you think, Sir, it was for this they died?”

Rights

As well as individuals writing to their local newspapers or to their local member of parliament, key interwar leaders of Indigenous activism used Indigenous Australian war service as part of their broader arguments for Indigenous rights as British subjects and Australian citizens. These activists were campaigning for specific legal and political rights on behalf of Indigenous Australians:

- the appointment of Aboriginal representatives to Parliament and Protection Boards

- moving Aboriginal issues to federal rather than state control

- the extension of universal suffrage in both state and federal elections

- the extension of pensions to Indigenous Australians

- the right to education, equality under the law

- the freedom to settle on self-governed reserves or self-owned land

Essentially, they sought the same rights available to non-Indigenous Australian citizens, and the recognition of Indigenous Australians as capable, intelligent and valuable members of Australian society.

Wiradjuri man William Ferguson and Yorta Yorta men Jack Patten and William Cooper were instrumental in organising Indigenous Australian activism across Victoria and New South Wales in the late 1920s and early 1930s. In 1938, to mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of British colonists in Australia, the three men organised the first Aboriginal Day of Mourning, to be held in Sydney on 26 January 1938. As part of the planned protests surrounding the day, Patten and Ferguson prepared a pamphlet to be distributed to protestors, newspapers and politicians: Aborigines claim citizen rights! In the pamphlet, the men explicitly linked Indigenous Australian war service with the equality and citizenship rights being campaigned for: “We were good enough to fight as Anzacs. We earned equality then. Why do you deny it to us now?” Patten and Ferguson were aware of the political rhetoric they were embracing by linking war service to citizenship rights, and deliberately mobilised the emotive power of Anzac to try to push for political change.

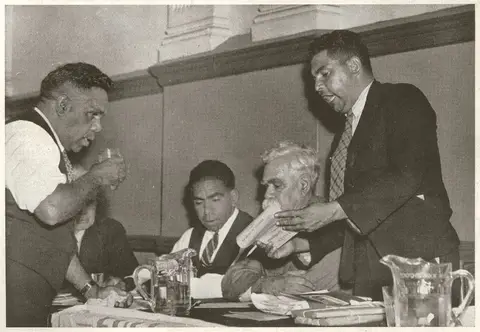

Tom Foster, Jack Kinchela, Douglas Nicholls, William Cooper and Jack Patten discuss a resolution as part of the Aborigines Day of Mourning on 26 January 1938. Photograph: Russell Clark, Q 059/9 courtesy of State Library New South Wales.

Of all the interwar Indigenous Australian activists, William Cooper is perhaps most famous for his discussion of war service as part of his activism. Cooper was the founder of the Australian Aborigines League, and an outspoken and dedicated campaigner for equal rights and the federalisation of Aboriginal policy. He often referred to the service of “at least one thousand Aborigines” in the First World War, describing their service as a “thankless task” to other activists and members of federal parliament. Cooper insisted that, partially due to their support of the war effort, Indigenous Australians should be “equally [as] entitled to the privileges of British citizenship” as any other Australian.

William Cooper had a strong personal reason for discussing Indigenous war service and sacrifice with such frequency. His son Daniel enlisted in the AIF in July 1915, aged only 20. He served on the Western Front with the 24th Battalion until 20 September 1917, when he was killed in action at Ypres when his shelter received a direct hit from enemy artillery. The inscription on his Imperial War Graves headstone, erected in Perth Cemetery in Belgium, reads simply “Father’s Son”.

Daniel’s death had a profound impact on Cooper and his activism. Daniel was frequently mentioned in letters, including when Cooper wrote to Minister for the Interior John McEwan in 1939. Responding to calls to create specific Indigenous Australian units for the Australian army, Cooper wrote:

I am the father of a soldier who gave his life for his King on the battlefield and thousands of coloured men enlisted in the A.I.F. They will doubtless do so again though on their return home last time, that is those who survived, were pushed back to the bush to resume the status of aboriginals … the aboriginal now has no status, no rights, no land and, though the native is more loyal to the person of the King and the throne than is the average white he has no country and nothing to fight for but the privilege of defending the land which was taken from him by the white race without compensation or even kindness. We submit that to put us in the trenches, until we have something to fight for, is not right.

Cooper’s stance was clear: if Indigenous Australians were to be expected to fight for Australia, they should be granted the rights of citizenship still denied to them by the Australian government and the Aboriginal Protection Boards.

Aboriginal Protection Boards. The “privileges of British citizenship” William Cooper fought for in memory of his son Daniel were not achieved in his lifetime. He died in March 1941, twenty-one years before the federal government took over control of Indigenous Australian affairs from the states. Indigenous Australians were not universally enfranchised until 1967, although veterans were granted voting rights in federal elections in 1949, thanks to activism from Indigenous communities and the Returned Sailors’, Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Imperial League of Australia (today’s RSL).

Despite the hopes of Indigenous Australian servicemen, activists and their communities, the First World War did not change their social or legal status in Australia. Nor did their participation in the Second World War. Jack Patten fought in the Second World War and was one of 53 Indigenous Australian Rats of Tobruk, before he was discharged in 1942 with shrapnel damage to his knees. After the war, he continued his activism alongside William Ferguson, campaigning against British atomic testing at Maralinga and establishing the Australian Aboriginal Elders Council of Victoria. Ferguson died in January 1950 after collapsing during a speech. Patten died in 1957 following a car accident.

Activists, their families and their supporters – many of whom were veterans or relatives of those who had died overseas while serving – continued to protest against the denial of rights and recognition well beyond the end of the Second World War. Through their activism, they challenged a political system that sought to keep them disenfranchised and oppressed, and a commemorative narrative that sought to minimise the contribution of members of their communities. In doing so, they refused to accept discrimination and dispossession as thanks for the sacrifice of their loved ones and fellow countrymen, fighting a battle that lasted long beyond the ceasefires and peace treaties that ended the two world wars.

Private Victorianno (Victor) Blanco, a pearl diver from Thursday Island wearing a traditional zazi, was one of around 6,500 Indigenous men and women to serve in the Second World War. 002931