A remote atoll in the Pacific was taken in 1943 at immense cost.

The United Nations World Tourism graph describes the remote Pacific nation of Kiribati as the least-visited country in the world. Kiribati (pronounced Kiribas) is a group of tiny islands; it is hugely expensive to reach, and once there, visitors find that infrastructure for tourists simply does not exist. There are no taxis, few places to stay, no swimming pools, no market, scarcely any shops. Kiribati is in a parlous economic position. Climate change is a major concern: the highest point on land is just three metres above sea level. Kiribati people face acute food and water insecurity, and lack even the most basic sanitation.

I visited Kiribati because my son was volunteering there, and it sounded interesting.

Aerial photograph of Betio 1943 with the triangular islet of Bairiki above. Photo credit Photo 80-G-83771 US Naval History and Heritage Command

Betio (pronounced Bayso) is the most populous of several islets forming the Kiribati capital of Tarawa. Just four kilometres long and 800 metres at its widest point, Betio is home to the port and business district. This ribbon of land is overflowing with rubbish: plastic bottles, wrecked cars, nappies, human waste and empty gas cylinders.

During the Second World War this tiny coral atoll was of enormous strategic significance; the Japanese-built airfield on Tarawa was a key objective, and over three days nearly 5,000 Japanese and 1,000 United States Marines died here. For concentrated, close-quarter fighting, there are few battles to eclipse Tarawa.

The battle of Tarawa is comprehensible and easy to visualise: it was brief, fought on absolutely flat terrain in a defined area, and even 81 years later, physical reminders of the battle are everywhere: big coastal guns, concrete gun emplacements, pill boxes and bunkers, portable command posts, amtracs (amphibious vehicles), and tanks.

The Japanese first attacked and occupied the Gilbert Islands (as they were then known) just days after their attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. A remote place with little connection to the rest of the world, Kiribati offered a geographic stronghold from which Japan could bolster its empire and expand its defensive perimeter. The population of Betio at the time was roughly 400. The Japanese destroyed all local boats to prevent people escaping. Gilbertese men were required to work, clearing trees and constructing gun emplacements; and when the work was complete, the entire population was forcibly moved off Betio. Without their canoes they had to walk, wade and swim to neighbouring islets.

In August 1942 more than a thousand Japanese soldiers and conscripted Korean labourers arrived to construct defences, a pier, and the only airfield in the region. They built bunkers, pillboxes, anti-tank ditches and trench fortifications. They installed heavy naval and anti-aircraft guns in concrete bunkers and gun pits. More and more Japanese soldiers arrived, bringing aircraft and tanks.

In October 1942, in a brutal show of force, the Japanese executed 22 Coastwatchers and civilians on Tarawa, two of whom were Australians.

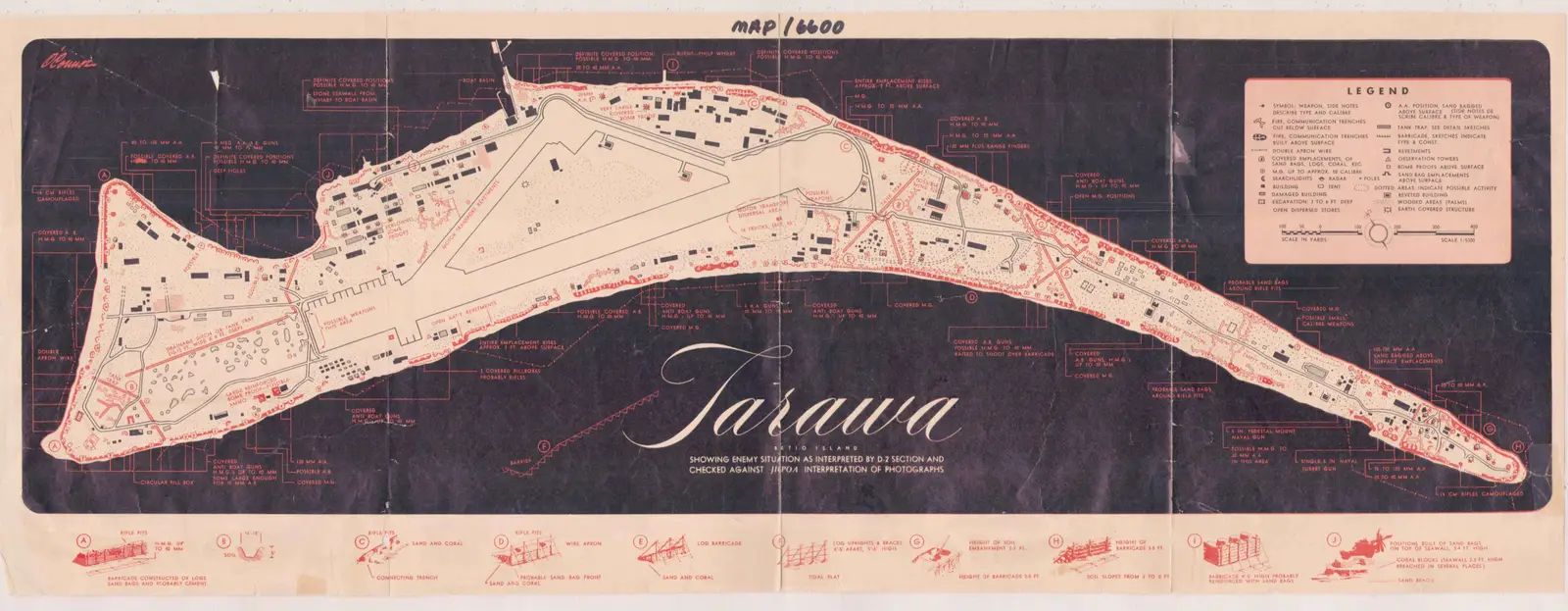

Map Image 6600 From the World War II: Gilbert Islands Collection (COLL/3653) at the Marine Corps History Division Official USMC Photograph

The build-up

The US had been watching the growing Japanese fortress on Tarawa. Starting in January 1943, American aircraft began flying photo reconnaissance operations, and in a prelude to the battle began bombing the islet in November.

And so the Tarawa chapter of Operation Galvanic (meaning a ‘sudden and dramatic experience’) began. This marked the beginning of America’s island-hopping advance across the Central Pacific. Hard lessons would be learned about amphibious landings on heavily defended islands, and many men would die learning them.

Mounting a large-scale marine invasion was a monumental task. It required the escort and protection of troopship convoys; co-ordination of air strikes by land and carrier-based aircraft, the timing of shore bombardments by battleships and cruisers; the disembarkation of Marines, and getting them onto the right beach at the right time.

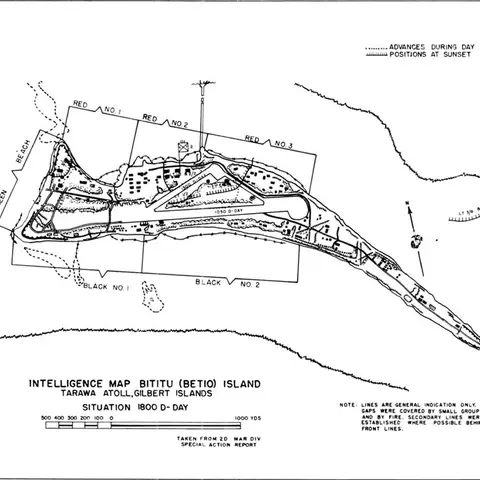

With close scrutiny of aerial photographs, detailed planning for the capture of Tarawa began. Careful assessment of the Japanese defences convinced American planners they must attack from the lagoon side on the northern shore. Three landing beaches were allocated: Red Beaches 1, 2 and 3.

The tip of Betio, Red beaches of the lagoon

The clearing in the centre of the islet is the airfield. Photo credit NH 95704 US Naval History and Heritage Command Collection

The depth of the water over the reef at the time of the landings was probably the most important factor in the whole operation. A group of old hands – expatriate men who had spent years on Tarawa – was gathered to provide expert opinion. The key factor was the state of the tides. Despite advice to the contrary, the attack was planned to take place when a low neap or dodging tide – with no more than 3 feet (one metre) of water over the reefs – might occur. One of the experts, a 15-year resident of Tarawa, was appalled that planners ignored his advice regarding the tides. But in the end, masses of ships and troops could not be kept waiting for another month or two, when the water would definitely be deep enough for landing boats to pass.

If the tidal advice was correct, amphibian tractors known as ‘amtracs’ were the only certain way of getting the men onto the beaches. Amtracs were slow and unarmoured, but they could serve as landing craft in the sea, cross submerged coral and drive straight up over land when they reached the shore.

The plan was that Marine assault troops would land with infantry, artillery, tank, engineer, pioneer and medical companies. Many of the Marines had come from a period of relaxation in Wellington, New Zealand, after a rough campaign on Guadalcanal.

Marines and sailors study a relief model of Betio en route to their invasion of Tarawa. Photo credit: USMC 67706, US Naval History and Heritage Command

A US invasion fleet totalling 51 battleships, cruisers and destroyers sailed for Tarawa, and on 20 November 1943 before dawn, warships began firing at Tarawa to knock out Japanese shore batteries while aircraft conducted strikes against the islet.

The bombardment went on for 40 minutes. When it stopped, the Japanese commander at Tarawa, Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, took advantage of the respite to move troops and guns to the defences facing the lagoon, from which it was now obvious that the landings would come.

The Japanese had built elaborate all-around defences on the island. They had four 8-inch/45 calibre shielded coastal defence guns; four 5.5-inch coastal defence guns; heavy anti-aircraft guns; beach defence guns with range finders, directors and searchlights; gun emplacements and pill boxes with connected trenches leading to bomb-proof shelters and coconut log barricades. On the beaches, rows of wire had been laid low to the sand, with machine-guns emplaced so flanking fire could be laid parallel to the wire and the shore. The Japanese had also built revetments (low walls to protect vehicles) and dug tank ditches.

From the water too, Japanese barricades seemed impregnable. Concrete obstacles had been placed on the reef; high barbed-wire fences were staked in the water, and anti-boat mines, anti-tank mines, magnetic and land mines were placed on the beaches and the fringing reef.

This was a seriously defended islet.

US Marines Corps land at Tarawa

“Marine Corps footage courtesy of the United States Marine Corps History Division and the University of South Carolina Libraries.” USMC 100837

The assault

Just after 0600 on 20 November 1943, two US minesweepers began to clear the entrance to the Tarawa lagoon, followed by seven minutes of aerial bombing.

At 0730 US battleships and cruisers blasted the tiny island from end to end for an hour and twenty minutes. This was the most concentrated pre-invasion bombardment, per square yard of ground, in naval history to that date. Firing was so intense that radio communications were severed between American carriers and broke down completely. The battle schedule then slipped, giving the Japanese respite to consolidate positions and bring their guns to sight on the approaching landing craft.

Despite the intensity, the preliminary air and naval bombardments were of little value – many of the shells missed their targets and Japanese troops were dug into well prepared bunkers. In fact, their bunkers and gun-pit shelters withstood the bombardment and were almost undamaged, although their communications were cut. When the shelling ceased, the Japanese moved to the landing beaches in readiness for the amtracs and men that would follow.

For the rest of the day, despite having no radio communications, the Japanese remained highly functional; but by nightfall the lack of communications led to a breakdown in control, which ultimately had enormous consequences. Meanwhile, 87 amtracs and boats formed up into three columns to make the voyage to the lagoon entrance, and then another kilometre to the beaches. Marines who had boarded at 0300 had been pitching about on the sea for nearly six hours, and many of them were seasick.

The first amtrac landed just before 0900 and came in under a barrage of heavy enfilading fire. Many amtracs were hit. Marines leapt out of them and into the water, causing every company radio to fail. Only the Marines in the amtracs were able to clear the reef. In places the sea was so low that there were stretches of exposed coral, exactly as predicted by the Tarawa ‘old hand’. The second and third waves of Marines, who came in Higgins boats, got hung up on the reef. These men, easy targets for the Japanese, had to jump into chin-deep water and it took hundreds of them half an hour to wade into shore. There was a great deal of confusion as some Marines were hit, others drowned under the weight of their equipment, and units became separated.

Marines who made it ashore were pinned down by heavy fire. By noon, though, they had secured Red Beach 2 and captured the first line of defences. By the first evening, thousands of Marines had reached the shore, but hundreds lay dead on the beaches and in the lagoon.

The Japanese had constructed coconut log and coral-stone seawalls that prevented most LVTs advancing. The bodies of Marines in the lagoon. Photo credit Marine Corps Photo 5-7 US Naval History and Heritage Command Collection

That first night of the battle, the Americans were hanging on to Tarawa by their fingertips. Most of the Japanese had survived thus far; but although they still had large amounts of ammunition, they failed to mount a counter-attack. They could probably have driven the Marines back into the sea. This oversight, when the Americans were at their most vulnerable, was their greatest mistake and probably cost them the battle.

Some have suggested that without radio communication to coordinate movements, and with their commander killed very early on, Japanese troops were fearful of taking the initiative and prepared to fight to the death.

Day two was a repeat of the first: communications cut or partial at best, and Marine landings in the face of Japanese machine-guns. But the Marines pushed forward; their artillery was landed, as well as tanks and bulldozers, and they gained a firm foothold on some beaches and inland positions.

Bodies of dead US Marines, sprawled along the invasion beach on Tarawa Island near a crippled American tank.

A Ha-Go tank turret in the courtyard of one of Tarawa’s few hotels, Betio Lodge. Photo credit Emily Hyles

By the second evening, when the Marines appeared to have gained the upper hand, the Japanese command bunker sent a final message to Tokyo: “Our weapons have been destroyed… everyone is attempting a final charge. May Japan exist for ten thousand years!”

The Marines continued to fight on the ground, and they were supported by naval and air bombardments. On the third day, hundreds of fresh reinforcements arrived to relieve the exhausted Americans. No support or reinforcements were sent to the Japanese.

Fighting was vicious and close, with the Japanese using grenade launchers known to the Allies as “knee mortars”, as well as hand grenades, booby traps and machine-guns. Marines countered with flamethrowers, and in one incident poured petrol, followed by a lit match, down a Japanese bunker air vent and sealed the exit with walls of sand.

Marines countered with flamethrowers. Photo credit is Frank Filan USMC Collection

Many Japanese, sensing defeat was inevitable, killed themselves. It was not in their nature to surrender. On the third and final night, waves of Japanese mounted frenzied banzai assaults of desperate hand-to-hand combat.

Then it was all over. The enemy were all dead.

1,009 Marines were killed and 2,101 had been wounded. Of the Japanese, 4,690 were killed – nearly the entire garrison – with only 17 captured and 129 Korean labourers taken prisoner.

All accounts of the aftermath of this battle recall the smell of nearly 6,000 corpses in the blazing equatorial sun. Burials were necessarily brief: corpses were laid in the existing tank ditches and bulldozed over.

The cost

Why did two nations spend so much to achieve so little? How could a tiny island just a few kilometres long, and having an all-around decisive defence doctrine be breached?

Marines on Tarawa recruited Gilbertese men to clear the dead and war debris. Betio villagers returned to find their subsistence way of life destroyed. All the trees and vegetable crops had been destroyed, the lagoon and beaches mined and fishing was disrupted for decades. No war reparations were paid, and the local people never regained their traditional ways, coming to rely on imported food and building materials.

Ruined Betio. The entire islet was heavily damaged. Photo credit 80-G-90388 US Naval History and Heritage Command

Tarawa was a well-documented battle. The Marine Corps had their own photographic section, which landed with combat troops on day one and recorded sequences in colour film. This film reached American audiences shortly after and shocked a nation with its graphic footage of dead Marines lying on beaches and bobbing in the lagoon.

For the Americans, the invasion of the Marshall Islands came next and the lessons of Tarawa had to be learned and refined in a few weeks.

- The biggest lesson was that battleships were not to be used as communications centres – their salvos had destroyed their own ship-to-shore radio links.

- Waterproof radios were now considered vital, and all equipment for amphibious attack needed to be lightweight.

- The amtracs performed very well and became mandatory on all amphibious assaults. It was accepted that the tide would play a key role in seaborne attacks.

Japanese portable command post. Photo credit Michael Garside

Today Tarawa remains dotted with relics of this time. Apart from the shore guns and bunkers, low tide reveals the remains of amtracs, American and Japanese tanks, and concrete reef obstacles. The Japanese Command Post remains solid, and is used to store unexploded ordnance which continues to emerge from the ground every few months.

Japanese command bunker 1943 with Ha Go tank. Photo USMC Photo credit NH 95704 US Naval History and Heritage Command Collection

Today the structure, bordered by a basketball court and church, is where UXO (unexploded ordnance) is stored. Photo credit Michael Garside.

US Navy built Quonset huts surround a burial ground in early 1944. Photo credit Marine Corps 22-17, Julian W. Moody

The Digital Transformation Office of Kiribati, where my son works, sits on what was a taxiway of the Japanese-built airfield, surrounded by the sites of temporary cemeteries. Post-war, the United States shipped all known Marine burial remains to Hawaii. None of the nearly 5,000 Japanese dead have marked graves; there are no war cemeteries on Tarawa, but there are certainly hundreds of men still there.

For anyone interested in war, Kiribati, remote and challenging as it is, is certainly an interesting place to visit.