Corporal Allan Chick’s story is one of survival against the odds, after surviving many horrors of war.

Allan Clifford Chick had a hard and unusual war, but his story began with a conservative and peaceful upbringing. He was born in 1920 to engine driver Edwin Chick and his wife, Evelyn in the sleepy coastal town of St Helens, Tasmania. Like so many in his community who had grown up in a working class home, he left school early and went into the fishing industry.

Chick’s peaceful life was disrupted by the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, and he decided to join the Second Australian imperial Force in June 1940. He was assigned to the newly raised 2/40th Battalion, comprised mainly of Tasmanian men like himself.

After completing training, the 2/40th was scheduled to deploy to Dutch West Timor to defend the Allied airfields there, but they were withheld from this deployment over fears that Japan might see it as a direct challenge. In an already tense and unstable political climate, Allied nations were hoping to avoid war with Japan, and were becoming increasingly nervous of Japanese militarism. But in December 1941 Japan’s intentions became clear when they landed troops on the east coast of Malaya and conducted devastating bombing on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor.

Portrait of Private Allan Clifford Chick

In response to the situation unravelling in the Pacific, the 2/40th was rushed to West Timor, where they joined Sparrow Force. They were deployed to Penfui Airfield, the operational base for the Hudson bombers of No. 2 Squadron RAAF.

The battalion was isolated and ill-equipped from the outset; their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel William Legatt, repeatedly requested reinforcements, supplies and artillery, but these were never granted.

A devastating series of events rapidly unfolded within weeks of the Japanese invasion of Malaya. Air attacks on the 2/40th’s position in West Timor began in late January, and by 15 February 1941 Singapore had also fallen. Less than a week later, No. 20 Squadron was withdrawn from Timor as the situation in the Pacific continued to deteriorate, and Chick and his comrades found themselves more isolated than ever.

On the morning of 20 February 1941, Japanese forces advanced on Timor, conducting an amphibious landing south of Koepang and dropping paratroopers from the east. Sparrow Force was badly outnumbered, and they knew it. They set about destroying the airfield before moving inland, with frequent small actions against the enemy in the process.

They held out for three days, by which time crucial supplies were running out and the numbers of sick and wounded were mounting. With the enemy closing in, Legatt was delivered an ultimatum from the Japanese: to surrender, or be bombed into submission.

Faced with the destruction of his command, Leggatt surrendered. Chick and the other survivors were interred on the island in a camp at Usapa Besar from February 1941. His normally regular letters home at once fell silent, an agonising experience for his mother, and for other parents like her who simply had no news. The first task assigned to the men of Sparrow Force was to set about clearing the corpses which littered the island, many of their own comrades among them.

After completing this horrifying task, they constructed a camp for themselves, having been left with no huts, cooking facilities or latrines for hundreds of internees at Usapa Besar. Chick and his comrades spent the first seven months of captivity there, living and working in appalling conditions. From July 1941, Chick and his fellow prisoners were moved from Timor and progressively dispersed throughout Japan’s conquered territories. Over the following months, Chick spent time in Java, before being moved to Singapore, where he was briefly interned at Changi.

“About a minute after the ship was struck, I suddenly felt water around my knees...I made for the hatch, the top of which had been blown away. I tried to jump up and failed… I remember being under water, and the next I knew I was on a raft floating in the open sea.”

Private Allan Chick

Hell Ship

On 3 June 1944, Chick was taken from Singapore on the Japanese cargo vessel Tamahoko Maru. On board he found himself among nearly 800 prisoners of war, crammed into conditions below deck that earned this vessel, and others like it, an enduring reputation as “hell ships”, steaming to Manila and on to Taiwan. On 20 June 1944, Chick and the other prisoners left Taiwan and continued their perilous journey towards Japan, again crammed below deck in unbearable conditions.

The Tamahoku Maru was sailing just off the coast of Nagasaki on 24 June 1944, when it was located by the American submarine USS Tang, which had been tracking the convoy since its departure from Singapore. Identifying its target, Tang fired a torpedo, achieving a direct hit on the forward hold, causing the ship to begin rapidly sinking.

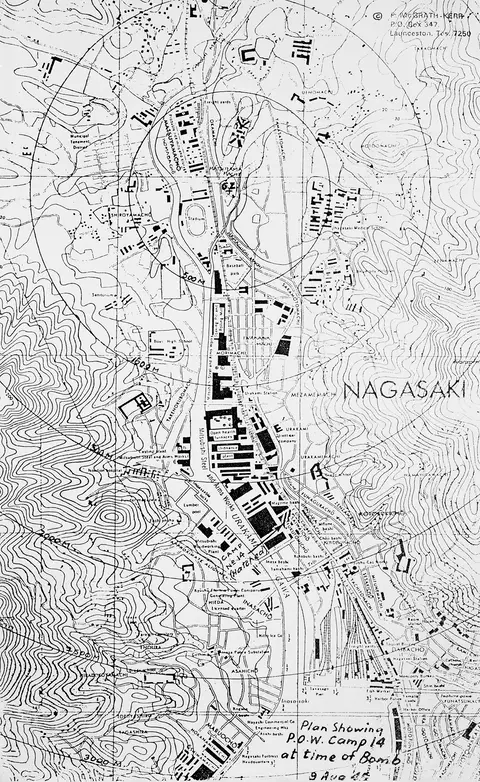

Map of central Nagasaki showing position of prisoner of war (POW) camp 14 in relation to the epicentre of bomb.

“About a minute after the ship was struck, I suddenly felt water around my knees,” Chick recalled. “I made for the hatch, the top of which had been blown away. I tried to jump up and failed. Then I found my hands over the edge of the hold. I presume I floated up there, as there were no ladders out of the hold … I remember being under water, and the next I knew I was on a raft floating in the open sea.”

The ship sank within two minutes, claiming some 560 lives. Those who survived were left in open water overnight, before being picked up by a Japanese whaling ship the following morning.

They were taken to Fukuoka Camp 14 on the Urakami River in Nagasaki. After being permitted a few days of rest, Chick was assigned to labouring duties and was sent to the Mitsubishi Foundry, where he worked alongside Japanese civilians. This proved to be a formative period for Chick, who was exposed to Japanese people and culture in way which differed from the experience of his comrades, many of whom had suffered from extreme cruelty at the hands of the Japanese military.

But Chick and his fellow prisoners still suffered, particularly from diseases such as beri beri, pneumonia, and malnutrition; Chick’s weight dropped to about 52 kilograms during the course of his imprisonment. The transition from tropical labour camps to the freezing winters of Japan similarly took its toll on the prisoners, who typically lived in basic huts constructed of thin boards and not equipped with fireplaces or stoves.

A terrific flash

Chick managed to overcome these hardships for more than a year, enduring the labour and harsh conditions while

attempting to stay out of trouble. On 9 August 1945, however, he and his fellow prisoners were given the day off, and were allowed to remain in the camp. Work at the foundry had ceased sometime earlier, owing to damage cause by earlier Allied bombing raids. Eager to keep busy, Chick began working on the frame of a small building in the camp; he was atop the structure with another prisoner when he was thrown from the roof by a massive explosion.

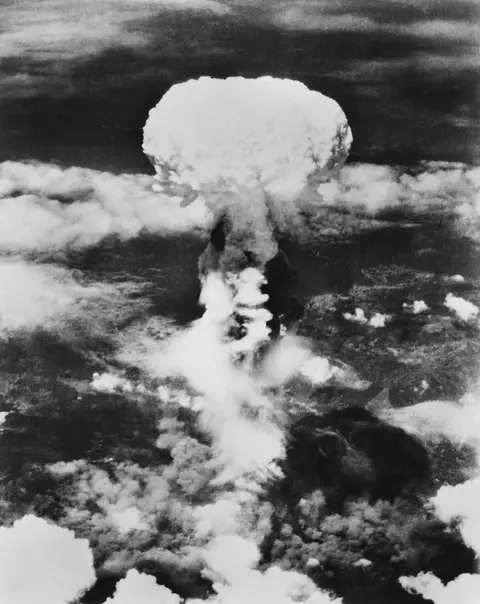

Nagasaki, Japan. 1945-08-09. The atom bomb attack on Nagasaki

“I was talking to another chap when there was a terrific flash of light. The next thing I remember I was standing on the ground. I’d been blown clean off the roof. I couldn’t see for a while and I was wondering what was going on,” Private Chick later recalled to a newspaper. He did not know it at the time, but he had just survived the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

“Fat Man”, as the second of the atomic bombs was known, had hit the city of Nagasaki and exploded only two kilometres from Camp 14. Chaos ensued as Chick, temporarily blinded by the blast, and the other prisoners were told to clear out of the camp.

Helping themselves to some Red Cross parcels, they fled before commandeering a horse and cart, making their way to higher ground, where they bore witness to the fires and devastation ravaging the city. They had been lucky.

The landscape surrounding Nagasaki had helped to contain the impact of the blast, while the Australian prisoners had been afforded additional protection from their red-brick barracks.

The next morning they returned to the remains of the camp, where they found a number of Chinese prisoners, who had been accommodated in flimsy wooden huts and had not been spared the atomic blast.

“Their fellows were lying there, no more than two feet apart, lined up on their beds,” Chick recalled. “I touched one on the foot and he crumbled. They were simply ash. They’d been burnt to a cinder.” The Chinese section of the camp had been separated from the Australians by a large concrete wall. When the bomb hit, it provided a small amount of shelter that helped to shield Chick and his comrades on the other side of the wall from the initial impacts of the blast.

Thousands more had not been so lucky. Across the city of Nagasaki there had been nearly 65,000 casualties resulting from the attack, with a further 135,000 casualties in Hiroshima. Japan could fight no longer and surrendered to the Allies less than a month later, on 2 September 1945.

Dutch prisoners of war (POW) from Camp 14 working in a Nagasaki shipyard.

The ruins of the Methodist Church in Nagarekawa, Hiroshima, one year after the atom bomb was dropped, seen from the top of the newspaper building which was one of two large buildings left standing after the bomb was dropped.

BCOF and beyond

Chick was recovered from Camp 14 soon after Japan’s surrender, as Allied nations began the enormous task of locating and liberating prisoners of war from remote locations across the Pacific. He was sent to Manila to await repatriation to Australia, and set foot on Tasmanian soil for the first time in four years on 16 October 1945. He spent a short period in hospital, and despite having endured so much during the war, decided against a discharge from the Army, which had been such a significant part of his life. Instead, Chick joined the Australian forces serving in the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF), which had been established to enforce the terms of Japan’s unconditional surrender.

In April 1946, less than a year after his liberation, Allan Chick began the journey back to Japan. On the voyage, he wrote to his mother: “Passed a lot of Jap fishing boats early this morning, everyone turning out to jeer at the nips and abuse them. A few who know my history are amazed that I didn’t throw everything at them including my false teeth. They reckon I must be pro Jap. One chap even asked me what it was like to be home again, some even reckon I’m coming home to some woman or other.”

News of the horrors suffered by so many prisoners of war only served to inflame the resentment already felt by many Australians towards the Japanese. Chick’s decision not to join in the anti-Japanese sentiment was contentious, but one influenced by his experiences with Japanese people and the suffering they had experienced after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As he told his mother: “Haven’t got the least desire to bash Tojo or anyone else. It’s a funny thing, but the people back home who never actually contacted the Nips are more hostile than the chaps who fought them.”

Chick disembarked in the city of Kure on 26 April 1946, and joined the 65th Australian Infantry Battalion. Over the following weeks, he and his comrades were involved in a huge variety of tasks, which included locating and securing military stores and installations, as well as dumps of Japanese military equipment that had to be destroyed. Chick and his comrades lived and worked among Japanese people, who had not escaped the misfortunes of war. Chick even returned to Nagasaki and Camp 14, where he took pictures of the devastation caused by the bombing, further softening his attitudes towards his former captors.

Nagasaki Medical College after the atomic bomb blast on 9 August 1945.

The site of prisoner of war (POW) Camp 14 Nagasaki as it appeared in 1947. The photographer, then TX3350 Private Allan Clifford Chick, 2/40 Infantry Battalion, was a prisoner in Camp 14.

Nagasaki, Japan, during the allied occupation 1948, Private Allan Chick of the 65th Battalion, with some of the war time employees of one of the city's foundries.

Fraternising

Allied soldiers came into frequent contact with locals, but strict non-fraternisation laws remained in place, aimed at preventing BCOF personnel from interacting with Japanese civilians. During the war crimes trials in 1946, Chick complained to his mother: “I am in Tokyo at last … one can sit by the window here and watch all the pretty girls go by, and believe me there are some really beautiful girls here … this non fraternisation order is a real farce. You can look out the window and see a Yank or two go by with a Jap girl and nothing is said!” This did not stop Chick, and many others, from seeing Japanese women away from the watchful eyes of the military police.

By September of 1946, Chick had begun dating a schoolteacher and former nurse, Haruko Kojima. Their relationship quickly became serious, despite the disapproval of Chick’s family, particularly his mother, whom Chick described as being “mad as a meat axe” over his new girlfriend. “If I should ever marry a Jap girl,” he told her, “I would never be silly enough to take her anywhere near St Helen’s, as people round there are too one-eyed for that sort of thing.”

Though the chances of Chick marrying a local seemed remote, his relationship with Kojima continued to blossom. By 1948, he seemed resolved in his actions, writing to his mother: “I have never met a finer girl than Haruko and hardly expect I ever will.” On 13 December 1951, Chick and Kojima wed at the Methodist Church in Hiroshima, another link with his wartime past. The new Mr and Mrs Chick were married in the eyes of God, but not in the eyes of the law, as marriages between service personnel and locals were still forbidden under anti-fraternisation laws. “So far no one knows,” Chick told his mother, “not the Army even. My wife sends her best wishes, not without certain misgivings however.” There is no surviving record of his mother’s reaction to the news, but given the hostility felt towards the Japanese more generally, one can imagine the apprehension with which Haruko Chick entered married life.

Photo from the Examiner Sat 11 April 1953

By 1951, BCOF had been effectively dismantled and the process of demobilising troops began. Many Australians opted to return home, while a number of others stayed to fight in the Korean War, which had been raging since 1950.

With his services no longer required in Japan, Chick was faced with a desperate situation. It was likely that he would be returned to Australia in the coming months, but he would not be able to bring Haruko with him, as their marriage was not recognised by the Australian government. He was not alone in this predicament, however. In fact, relationships between Australian BCOF personnel and Japanese women had become so common, that the Menzies government was eventually forced to grant permission for marriages to take place legally.

So, on 3 October 1952, Allan and Haruko were married again, this time in a legal ceremony performed at the British Consulate in Japan. Less than six months later, they embarked together on the aptly named New Australia, and began the long journey home to St Helens in Tasmania. Allan and Haruko would find themselves among more than 650 Australian–Japanese couples who made their homes in Australia between 1945 and 1965. It was undoubtedly a daunting move for Haruko, and women like her, to leave their homeland behind and travel to a new country where a warm reception from the Australian public was less than certain.

On 10 April 1953, Allan and Haruko Chick arrived in Tasmania. For Allan, it marked the end of a 13-year career in the Australian Army, while for Haruko it marked the start of her new life. Undoubtedly the couple were nervous as they met the sea of faces which awaited them on their arrival; it was impossible to predict how people would react. Yet, as they stepped onto the tarmac, Allan and Haruko were warmly welcomed by family, friends and well-wishers bearing gifts and flowers. At first avoiding the cameramen, the shy and quietly spoken Haruko was quickly welcomed into the Chick family circle, telling one reporter from the Launceston Examiner, that she was “happy to be in Tasmania.”

Allan and Haruko Chick stayed in Tasmania for several months as they grew accustomed to their surroundings. They later settled in the Victorian town of Heyfield, where they appear to have lived a quiet but happy life together for more than sixty years.

In 2013, Allan died, predeceasing Haruko. It is not known what became of her after his death but it is clear that they shared a bond that remained unbroken through war, culture and prejudice, a bond that allowed them to build a new life together and become embedded in the fabric of post-war Australia.