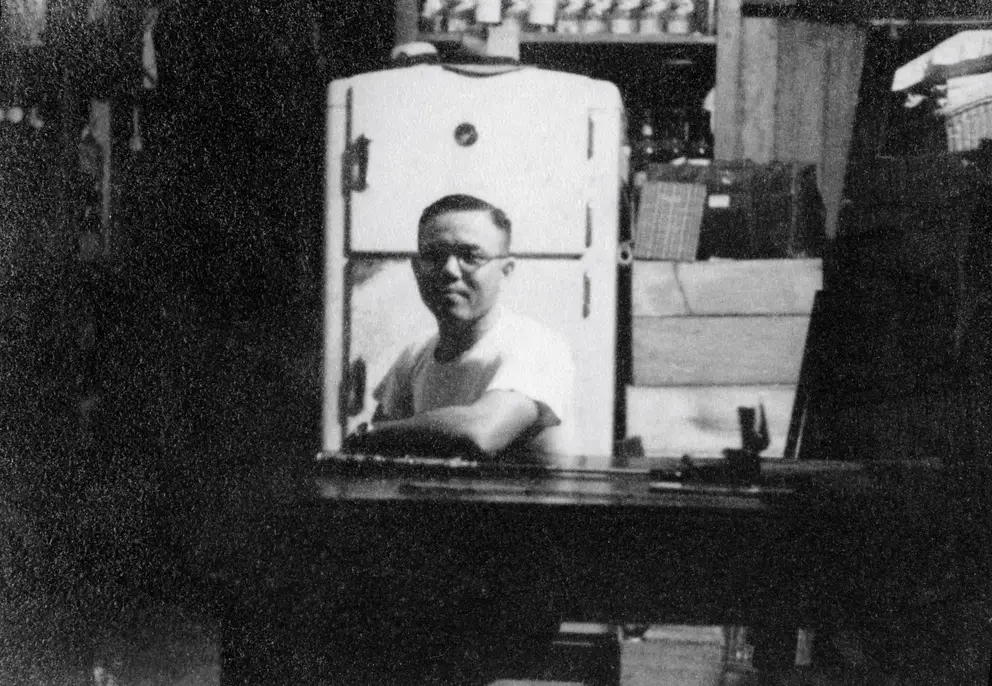

A local merchant from Thailand who helped prisoners of war on the Thai–Burma Railway.

Of the million photographs that the Australian War Memorial holds in its collection, only a small number focus on the perspective of local communities in places where Australians served. One photograph shows a local merchant from Thailand, who helped thousands of Australian, British, and Dutch prisoners of war on the Thai–Burma Railway.

Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu in his General Store on Parkprag Road, which he still ran while aiding prisoners, 1943.

During the war, Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu was contracted by the Japanese Imperial Forces to deliver supplies to the prisoner of war camps. Disturbed by the treatment of the prisoners, he began an underground effort with his wife, Surat, and his daughter, Panee, to aid them. Boonpong would travel aboard a small boat on the Kwai Noi River to sell goods to the Japanese, a ruse that gave his family access to the labour camps as far north as Tha Khanun. They reached many camps, including Kinsayok, Hintok, Konyu, and Chungkai.

At the camps, they smuggled supplies to the prisoners’ commanders, such as British officer Phillip Toosey, who would then distribute the aid within the camps, including medical supplies to doctors such as Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop. The Sirivejjabhandu family were also able to smuggle money, food, and batteries for illegal radios, which gave the prisoners access to the outside world. A resistance network in Bangkok provided the funds to buy these essential items for the prisoners. Boonpong also safeguarded prisoners' valuables, such as watches and jewellery, which he bought and returned to them after the war.

This work came at great risk to the family. Under Japanese occupation, any interaction with a prisoner was punishable by death. The family’s safety was constantly tested; their shop was searched twice by the Japanese, who suspected Boonpong's subversive activities. At one point his contract was terminated. Despite these setbacks, his family continued to help prisoners in secret.

Surat Sirivejjabhandu at the family's store, 1943.

Panee Sirivejjabhandu c. 1943.

Boonpong Sirivejjabhandu (seated) with members of the Allied War Graves Commission: Driver “Scotty” Carlyle, Lieutenant Jack Leemon, and Captain Bull, September 1945.

When the Japanese surrendered in August 1945, a generation of Australian servicemen and servicewomen returned home. But the local Thai population was left to manage the war’s economic and psychological impact on their society. More than 100,000 indentured labours, known as Rōmusha, who had been taken from across Asia to work on the railway, were stranded in foreign lands and separated from their families.

Boonpong himself struggled significantly after the war’s end. In September 1945, he was shot, almost fatally, by Thai police – probably in retaliation for his role in the war. The financial strain of his wartime efforts also lingered. In 1950, British ex-prisoners heard that Boonpong was "on hard times due to trading losses”. In response, a fundraising effort began. When word reached Australia, former prisoners started a donation campaign to support him. That brought Boonpong and his family to the attention of the Australian government, which awarded him £500 in recognition of his life-saving support for Australians.

Accepting the award, Boonpong responded, “Such services as my family was able to render to Australian and Allied POWs were performed in the name of humanity and really call for no reward.”

Boonpong, Panee, and Surat were some of many Thai people who resisted the Japanese during the Second World War. Theirs is also just one story from among millions of civilians who were affected by the conflict in Asia.