The Memorial’s V2 rocket and Meillerwagen trailer have many stories to tell.

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, Allied armies invaded German- occupied France, heralding the beginning of the end of the Second World War. Soviet armies would soon launch a massive offensive against German forces in Poland. With the tide of war turning and Germany on the defensive, the Nazi propaganda ministry hinted at Wunderwaffen, superweapons that would turn the tide in their favour.

The V2 rocket on display in Trafalgar Square, London in September 1945. Photographer: Cyril Issac

During the Blitz, German bombers had attacked British cities, causing enormous damage and loss of life; roughly 43,000 people were killed and two million made homeless. In June 1944, however, a new threat appeared, a ground-launched missile that flew without a pilot until it came crashing down and blew up. Dubbed the Vergeltungswaffe 1 (Vengeance weapon 1), the first V1 flying bombs hit London on 13 June 1944.

Fighter planes over the English coast, anti-aircraft batteries in Kent, and barrage balloons around London destroyed more than 4,000 V1 missiles. Flying noisily at a maximum speed of 420 mph (675 kph), they could be shot down or knocked off course.

They became known as buzz bombs or doodlebugs, as people could hear them coming and try to take shelter. It was different with the second vengeance weapon, the V2. It travelled at almost five times the speed of sound, giving no warning before impact, and it flew too high and fast to be intercepted.

The first V2 hit London on 8 September 1944; over the next few months, nearly 1,400 more would strike. Powered by a rocket engine burning a mix of alcohol-water and liquid oxygen, the V2 blasted its way to the edge of space before falling back to earth at supersonic speed. The Royal Air Force began bombing V2 launch sites identified by Allied radar operators, who would guide fighter squadrons to the location. To avoid Allied aircraft attacks, the Germans typically launched from heavily wooded sites, often near civilian areas, and often at night.

V2 Fast Facts

Development started: 1936

First successful test launch: 3 October 1942

First successful operational launch: 8 September 1944 against Paris

Length: 14m

Weight: >12,700kg

Payload of explosives: 725kg

Speed: 5x speed of sound

Horizontal range: 320km

Altitude: >80km

Time from launch to landing: 5 minutes

Killed: 5,000 in attacks, 10,000 in forced labour

Development and manufacture

Research and development of the V1 and V2 had taken place at Peenemünde, a special weapons research establishment set up in 1936on the German island of Usedom in the Baltic Sea. In early 1943 various Allied sources indicated that rocket research was taking place there. On the night of 17 August 1943, 596 bombers were directed against Peenemünde, among them the Memorial’s Avro Lancaster “G for George” of No. 460 Squadron, RAAF. Despite a vigorous response by German night fighters, the Peenemünde raid inflicted heavy damage. While the facility continued operating on a reduced scale, much of its work was moved elsewhere.

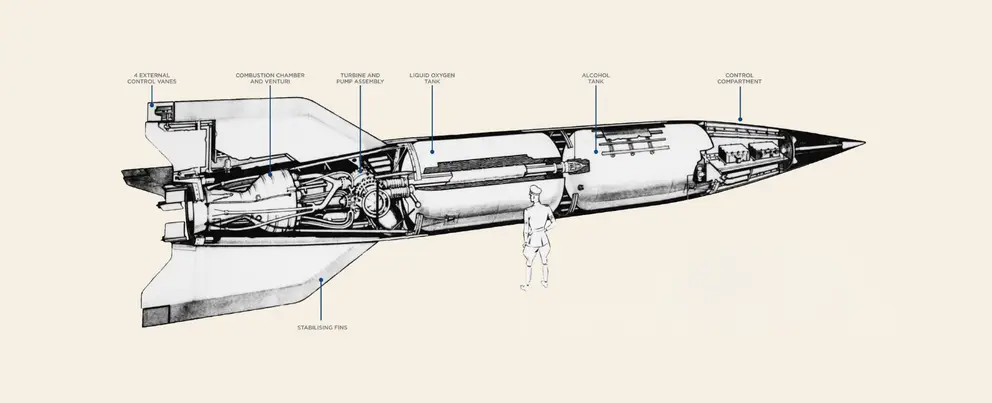

Illustration based on diagrams of the V2 rocket components.

The V2 weapons were manufactured by slave labourers – tens of thousands of civilians from occupied Europe, subjected to a brutal regime of starvation, torture and frequent executions.

While about 5,000 people died in V2 attacks, it is estimated that between 10,000 and 20,000 prisoners from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp died while being used as forced labour to build V2s at the Mittelwerk factory, which was built underground to avoid Allied bombing.

Among the survivors of those who worked at the Mittelwerk factory was Alexander (Sandor) Bartos, a Jewish Hungarian labour corps soldier who arrived at Dora in December 1944 and was moved onto the V2 production line in early February 1945.

100 yr old Alexander (Sandor) Bartos was a prisoner of war and worked on the V2 production line in early February 1945. He visited the V2 at the Memorial in March 2022.

Photographer: David Whittaker, AWM2022.4.20.35

The space race

The threat posed by the V2 ended in March 1945 as the Allies advanced across France, Belgium and Holland, capturing launch sites. While the V2 had not had a significant effect on the outcome of the war, its development did lead to the intercontinental ballistic missile of the Cold War, as well as playing a part in the development of space exploration. With the end of the war, a race began between the United States and the USSR to retrieve as many V2 rockets and staff as possible.

More than 300 rail cars filled with V2 engines, fuselages, propellant tanks, gyroscopes, and associated equipment were taken to White Sands Proving Grounds, a US military testing area in New Mexico. Wernher von Braun and more than 100 key V2 personnel had been captured or surrendered to the Americans. They were taken to the United States, where they became part of a fledgling space program. In 1946, a modified V2 launched from White Sands took the first photograph of Earth from space. The first animals sent into space were passengers on board modified V2s. Von Braun was appointed director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960. In 1969, his Saturn V rocket propelled the Apollo 11 mission on its way to the moon.

The journey to the Memorial

In 1947 two V2 rockets were brought to Australia. One was intended for the Australian War Memorial, but after being transported between various towns it ended up as a gate guardian at Holsworthy Barracks. The other rocket was sent to the Long Range Weapons Establishment in South Australia. This rocket was accepted into the Memorial’s collection in 1957. With the rocket came its Meillerwagen, the trailer used to transport the rocket, erect it on its firing stand, and to act as service gantry for fuelling and launch preparation.

A V2 rocket, parked in Martin Place Sydney, gives the public the opportunity to view the weapon. September 1957.

An RAAF convoy, transporting the V2 rocket through Sydney, September 1957.

In Adelaide, the V2 and Meillerwagen were prepared for display. The V2 had originally been painted dark green, and covered with a preservative spray for the sea voyage; now it was painted in a black-and-white chequer pattern for the Army and Lord Mayor’s display in February 1948. Kept in storage between 1948 and 1957, the V2 was periodically showcased, as well as being painted silver.

On 30 July 1957 the V2 was unloaded at RAAF Base Richmond; photographs show that it had suffered a break between the fuel compartment and engine. The V2 and Meillerwagen came to Canberra in October 1957 and were kept at the Memorial’s Duntroon Store. In the 1970s they were moved to the Memorial’s Mitchell A Annex, and in the 1990s to the Treloar Technology Centre, where conservation treatment began.

Conservation

The V2 was dismantled to inspect the level of damage it had taken and to determine conservation requirements. It was dismantled as it had been assembled: removing the tail section, engine, warhead, control compartment, and finally the centre section. A number of paper tags were found, naming different parts of the rocket in German and English. These had been placed during Operation Backfire – part of the Allied attempt to acquire German technology during and after the Second World War. These tags were documented and safely removed and sent to the paper conservation team for treatment before being placed in storage.

The V2 rocket being assessed by the conservation team at the Memorial. REL12324

The Meillerwagen trailer is complete, one of only three such examples still inexistence. The rocket itself was largely complete, retaining one of its two gyroscopes in its control compartment, the fuel tanks and engine. Part of the outer skin on the port side (as it sits on the trailer) had been replaced with thin sheet metal, and part of the plating on the starboard side had been removed to expose the turbine. The graphite control vanes at the base of the rocket were missing, and some of the fabric tape applied over panel joints had detached. Parts of the V2 structure were missing or damaged because of corrosion, most of which had formed during the 1940s and 1950s. Parts of the interior had been made in bright mild steel with no paint to inhibit corrosion; this caused some areas to corrode from the inside out. Glass wool, used as insulation against heat, had been left behind the skin; this created a trap for water, shortening the life of the skin and internal rocket components.

As conservation of the V2 and Meillerwagen continues, Memorial staff are excited at the prospect of being able to use these items to tell new stories at the Memorial: the stories of Australian bomber crews who fought to defend the Allies against V2 attacks, the casualties of V2 bombing raids, those enslaved to work on V2 factory lines, and the connection between V2 rockets and the space race.