Lieutenant Alexander MacNeil's exploits at Bullecourt placed him among the bravest Australians of the First AIF.

The Minenwerfer shell described a graceful arc as it headed directly towards the Australian front line. Directly in the shell’s path were two men who had been sending greetings in the form of rifle grenades to the Germans opposite. One man who saw the shell yelled a warning, but it was too late for anyone to do more than duck their heads. The shell landed and detonated with a thunderous explosion.

Corporal Alexander MacNeil c. 1915. Image courtesy of State Records of South Australia GRG26/5/4

One of those men on top of the dugout was Lieutenant Alexander MacNeil of the 10th Battalion. MacNeil, a native of Inverness, Scotland, had arrived in Australia at the start of 1913 and was working as a boilermaker’s assistant in the Port Adelaide shipyards when the First World War began. He joined the 10th Battalion at Morphettville Racecourse, near Adelaide, on 29 August 1914 and – with three years’ prior service with 4th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders (Territorial Army) – soon found himself promoted to lance corporal.

MacNeil and the 10th Battalion went ashore at Gallipoli as part of the first wave in the pre-dawn hours of 25 April. Weeks of heavy fighting ensued as the invaders fought for a toehold on Gallipoli. Like so many others, MacNeil developed dysentery from the poor diet and hygiene. He refused to be evacuated and remained with the battalion throughout its time on the peninsula.

By August MacNeil, now a sergeant, had been introduced to a weapon that would play a major part in his life over the next three years: the mortar.

One of the first mortars seen and used by the AIF was the Garland trench mortar, which featured a smooth-bore barrel fixed at a 45 degree angle and was fired by a powder charge. By October there were 7 Garland mortars with the Australians on Gallipoli, one of which was with the 10th Battalion. But it would be on the Western Front, with a mortar far superior to the Garland, that MacNeil would really come into his own.

From the earliest days at Morphettville and throughout the Gallipoli campaign MacNeil had gained a reputation as being earnest, self-effacing, a deep thinker and decisive in action. He was popular with officers and men alike and it was no surprise to many, except maybe MacNeil himself, when he was commissioned as a second lieutenant on 16 March.

Soldiers of the 10th Battalion take a break during an exercise near Mena, Egypt. c. 1915

To the Western Front and a close call

The 10th Battalion sailed to France at the end of March and by mid-April had arrived in the Nursery Sector. At this time the 10th’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Price Weir, formed the Scouting, Intelligence and Sniping Platoon. In command was Lieutenant William McCann, another original member of the battalion, with MacNeil as his second in charge. All 40 members of the platoon were handpicked and proven veterans. McCann, MacNeil and their platoon trained hard, making several forays into the front line and no man’s land to hone their craft.

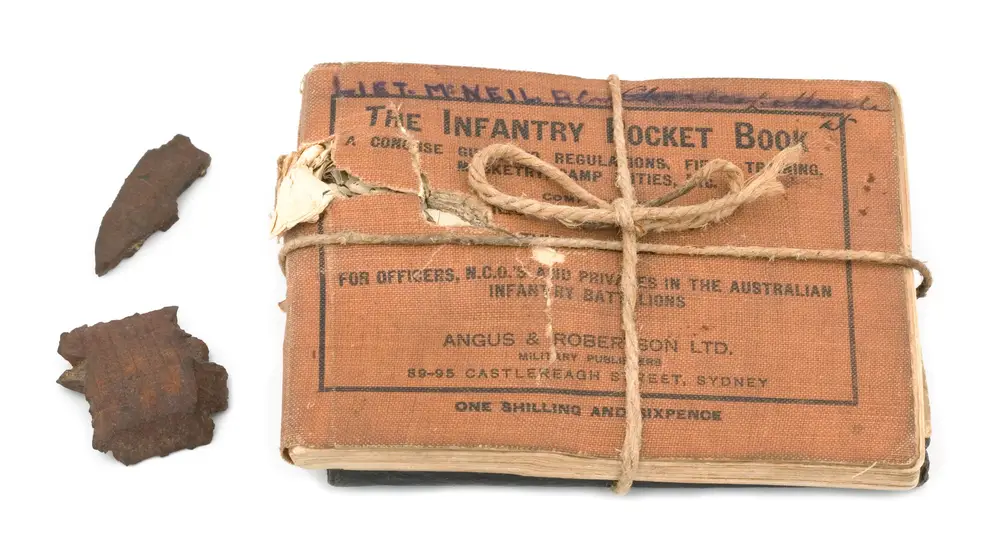

The 10th Battalion entered the front line in the Pétillon Sector in June, occupying positions on the right of the 3rd Brigade’s line. The Germans gave the newcomers an unwelcome introduction to the Western Front, subjecting the Australians to a near constant barrage of artillery and mortar fire. On 13 June MacNeil had a brush with the Reaper’s scythe when he was hit in the chest by two chunks of shrapnel during one such bombardment. His pay book and platoon nominal roll book, kept in his right breast pocket, deflected the shrapnel pieces downwards, filleting his skin, but not penetrating his abdominal cavity. He was evacuated to England and the shrapnel was removed in the 3rd London General Hospital at Wandsworth. After his operation, the surgeon presented him with the two pieces of shrapnel, which he kept. He would also have also learned of his promotion to lieutenant, which had taken effect while in transit to England.

After convalescing and being declared fit, MacNeil returned to the 10th Battalion in mid-August. The battalion, then located at the brick fields near Albert, was in the process of returning to the front line for an attack near Mouquet Farm. The 10th had already been battered at Pozières the previous month and suffered further heavy casualties in its attack near Mouquet Farm, though MacNeil remained unscathed.

Shrapnel and MacNeil's pocketbooks that saved his life in June 1916.

Tempting fate in the Ypres Salient

The battered 10th Battalion was sent to positions around Hill 60 in the Ypres Sector in September. At this stage, Ypres was a quiet sector, but MacNeil was one of many still keen to take the fight to the Germans. On the 27th of September MacNeil and Sergeant George Guthrie, another original member of the battalion, sat on top of a dugout conducting their own private war with the Germans by firing numerous rifle grenades across no man’s land. Company Sergeant Major Joe Watson, who was nearby, described what happened next in a letter to his mother:

Watson, a well-known Australian Rules football identity in South Australia had played in the Port Adelaide Magpies 1914 premiership winning game in September 1914, only weeks after joining the 10th Battalion. The battalion’s war diary entry for 27/28 September reported that “we annoyed the Boche during the night with rifle grenades. He retaliated but did no damage.” Sergeant Guthrie, despite the shrapnel hit to his shoulder, remained on duty. He would be badly wounded, and Watson mortally wounded, at Bullecourt the following May.

MacNeil with a garland trench mortar on Silt Spur at Anzac, August 1915.

MacNeil and the 10th Battalion returned to the Somme in October and endured the bitter winter of 1916–17 around Gueudecourt. In January he was seconded to the 3rd Australian Light Trench Mortar Battery, becoming the unit’s second in command. His commanding officer was an old friend from the 10th Battalion, Captain Alan Newland. The battery was equipped with the then-new and still very secret 3-inch Stokes mortar. It had a smoothbore tube with a firing pin at its base. It was kept in place by a bipod which had rudimentary sights attached and a baseplate to absorb recoil. It was capable of firing bombs up to 800 yards and was served by a crew of two or three men.

When the German Army began its withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line in February, MacNeil went into action with his new unit for the first time at Eaucourt l’Abbeye, where despite an initial lack of front-line ammunition, the unit performed well after being resupplied. A further action followed soon after at Bazentin, where the mortarmen again performed well.

Burnout before Bullecourt

March saw the 3rd Light Trench Mortar Battery training behind the lines before returning to action in April. MacNeil was in charge of the reserve guns on 15 April during the German attack at Lagnicourt which, after a stiff fight, was driven back with heavy losses. The remainder of the month was taken up with training exercises and recreation.

On 4 May the battery received orders to move to Noreuil in preparation to support operations against the Hindenburg Line. By the following evening, the battery were in their positions in part of the Hindenburg Line that had been captured the day before. They were soon in action, providing fire support against enemy positions, while being subjected to lively and constant German artillery fire.

Brigadier General Gordon Bennett, who was in command of the 3rd Infantry Brigade at the time, wrote an article for Smith’s Weekly for the anniversary of Bullecourt in 1930. He recalled that MacNeil had visited him at 3rd Brigade Headquarters. Clearly nervous and after a considered pause, MacNeil began, “The fact is, sir, I’m done. My nerves are gone. I feel I can’t stand it any longer. Could you arrange for me to have a few months rest at the Training Camp in England?”

Bennett, who well knew this officer’s fighting qualities and reputation as a leader in battle, promised that “immediately we come out of the line you will be sent to England for a long rest. In the meantime I know you will do your best.” MacNeil, both clearly relieved and embarrassed in equal measure, replied, “Thank you sir. I will, and er-er- I’m sorry I feel as I do.” The meeting over, he saluted and left Bennett’s dugout.

A VC on any other day

In the early hours of 6 May after an 18-hour bombardment, the Germans launched an attack in great strength. Where the attack fell against Bennett’s 3rd Brigade, the Australians were forced in places to conduct a fighting withdrawal, while others held on at makeshift bomb stops (defensive barriers built across their own trenches).

MacNeil had been in charge of a bomb stop in the O.G.1 trench during the night, where he and his men kept the Germans at bay in a fierce bombing duel. When Captain Newland was wounded early in the morning, MacNeil took charge of the battery. His four mortars were sited to defend the Australian gains at the O.G.1 trench, and as the German infantry and bombers began a flanking attack, the mortars were soon spitting their hail of death. The German advance was such that MacNeil’s mortar crews were unable to continue shortening their range, for fear of hitting their own men; but they kept firing, attempting to slow the German advance.

Australian soldiers receive instruction in the use of the 3 inch Stokes mortar, c December 1916.

Another German attack led by two flame-throwers advanced down O.G.1 and reached the bomb stop that MacNeil and his men had been defending. The closest mortar crew to the German attack, led by Corporal Julian North, was ordered to withdraw: by this stage the nearest German soldier was some 10 yards from his position. While several men carried their mortar out of danger, North and others threw Stokes shells and bombs to keep the Germans at bay before withdrawing themselves. North would later be awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his courage and leadership during the battle.

The German advance was relentless; one man with a flame-thrower let the attack along O.G.1, with German bombers close behind. A second flamethrower brought up the rear of the assault. MacNeil, not wishing to lose any of his men or mortars, ordered his remaining crews back. Now alone in the trench and armed only with his service revolver and several bombs, he had moved to a position that Charles Bean, the official historian, described as a ‘crevice’ when the first German armed with a flame-thrower rounded the corner. As a jet of flame roared past him, MacNeil threw a bomb, killing the German. Despite the presence of the second flame-thrower, MacNeil fought on alone for a short time before being joined by Captain Jim Newland VC and some of his men from the 12th Battalion. The makeshift Australian section had brought with them a box of bombs, and with these they held the second flame-thrower back from their position.

MacNeil had left the safety of the trench and was bombing from a shell hole when Newland was wounded in the arm and chest. With their officer wounded, the position began to give way and the German attack was renewed. Seizing the initiative, MacNeil picked up a Lewis gun and moved from shell hole to shell hole towards the second German carrying a flamethrower.

As the man advanced past him down the trench, MacNeil stood: firing from the hip, he emptied the Lewis gun’s magazine into the soldier with the flamethrower and those around him. As he fell, the flamethrower’s nozzle was turned back towards other German soldiers, immolating several more. The German attack faltered and the survivors began to withdraw. Not yet done, MacNeil, seeing the Germans’ confusion, ran back to his original position and picked up six tenpound mortar shells.

After climbing back on top of the parapet, he ran along it, dropping a mortar shell into each traverse still occupied by the Germans as he went past. In this manner, he cleared 50 to 60 yards of trench that had been captured by the enemy. Still reeling from the psychological effects of the flame-throwers, the Australians were slow to react; but MacNeil rallied

as many men as he could and led a counter-attack, regaining all of the lost ground and a further 50 yards of trench line. Here, he erected another bomb stop and held on against all further attacks.

As dawn broke, and the desperation of the situation was realised, a company from the 10th Battalion was despatched to relieve MacNeil and the other survivors of this all night battle. As the fresh troops entered the trench, it was a charnel house, lined with dead and wounded Australians and Germans. MacNeil was described as being “white as a sheet, blood streaming down his face from a head wound, and hardly able to stand.” He threw his arms around the relieving officer’s neck saying, “Thank Christ you’ve come, old man. We’re all in.” Only six other exhausted men remained on their feet.

Alexander MacNeil (centre front) attended the mortar instructors' course at Lyndhurst in November 1917. His DSO ribbon is above his left breast pocket.

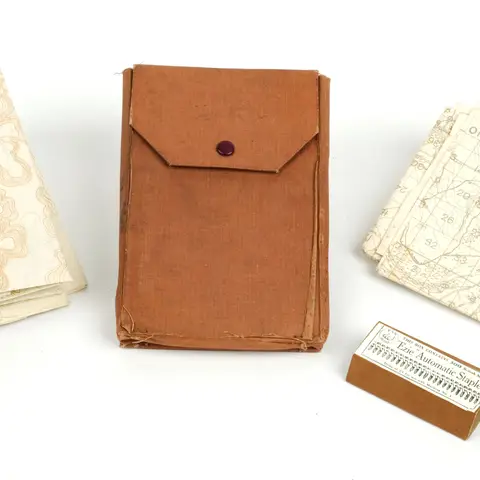

MacNeil carried these maps in this waterproof carrier during his last actions near Habonnières in August 1918.

To England and new beginnings

Bennett recommended MacNeil for the award of the Victoria Cross. Most thoroughly deserved as that award would have been for this action, MacNeil ultimately received the Distinguished Service Order. The 3rd Brigade was relieved on 10 May, and by the end of the month was in rest positions well behind the lines. Bennett remained true to his word and in late June sent his exhausted young officer to England; after attending a medical board he was graded as unfit for service. During his recovery he met his future wife, Mary Rose, a staffer at the hospital where he was being treated. At the end of July he reported as an instructor to the 3rd Training Battalion; it was here he learned of his award of the DSO.

MacNeil was posted to the Southern Command Bombing and Gunnery School at Lyndhurst in early November. The school, which opened in 1915, had been originally set up to train soldiers from all over the British Empire in the use of

grenades in combat. By 1917 an artillery range had been added to train soldiers in the use of mortars. MacNeil joined the 51st Course for mortar instructors, passing with distinction. He was further rewarded for his service when he was mentioned in General Sir Douglas Haig’s despatch of 7 November 1917 for “distinguished and gallant service and devotion to duty in the field during the period 26.2.17 and 20.9.17.” MacNeil and Mary were married on 9 February 1918 at All Souls Church in London and enjoyed several months together while he continued to serve as an instructor.

In June he returned to France and rejoined the 3rd Light Trench Mortar Battery. He took part in the 10th Battalion’s successful capture of Merris in July, where he was again commended, this time by the 10th Battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Maurice Wilder Neligan, for his work keeping seven mortars in action and providing vital fire support throughout the battle. When the allies launched their major offensive on 8 August, MacNeil and his comrades were once again in action, supporting the 3rd Brigade as it advanced. On 15 August MacNeil was slightly gassed, but remained in action.

His last action of the war took place on 25 August 1918 at Madame Wood near Harbonnières. During the attack MacNeil and his men captured a German 77mm field gun, turned the gun on its former owners and began firing over open sights. The action continued for several hours; every available man was put to work ferrying ammunition to the gun, which attracted ever-increasing fire from the Germans. When MacNeil finally ceased fire, he had fired 100 artillery rounds.

Only days later the unit was relieved from the front line. An exhausted MacNeil was forcibly evacuated to England where he again fronted a medical board. He was found to be still suffering from being gassed, compounded by an ever-worsening stomach complaint that stemmed from having had untreated dysentery on Gallipoli.

He remained in England and took his discharge from the Australian Imperial Force in London on 3 February 1919. His first daughter Julia was born the same year. MacNeil returned to the ship repairing trade until July 1922, when he and his family emigrated to Australia and settled in Sydney. A second daughter, Sarah, was born in 1924. Little has been found so far of his later life in Australia, but in the late 1960s he donated his medals and many of his souvenirs, including the shrapnel removed from his body. He passed away on 30 November 1972, aged 80.

Alexander MacNeil had served with great courage and distinction from Gallipoli to the Western Front, yet when he returned to his adopted country in 1922, it was to a life of anonymity, unless he was reunited with old comrades, among whom his story lived large. Certainly his former brigade commander never forgot the young officer who had the courage to face his fears, despite being near to breakdown, and who went on to perform the deeds that restored a dire situation and would have certainly been a VC on any other day.