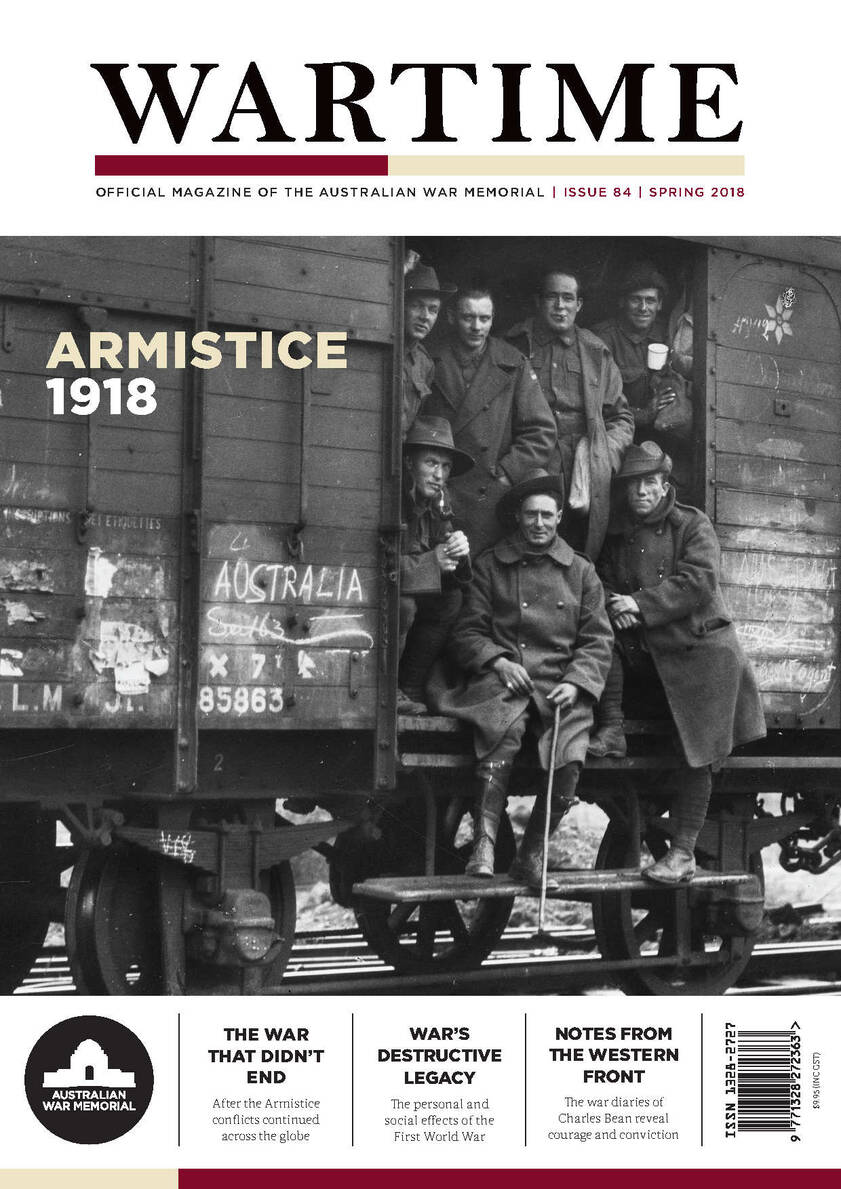

The Armistice of 1918 is seen as ushering in peace, but conflicts continued across the globe.

There is a conventional story we all learned at school. Here it is in a nutshell: the First World War ended at 11 am on the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918. The troops came home. The interwar years began. Twenty-one years later, interwar turned into wartime, which in its turn ended with a bang after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

If only history were as neat as that, or that it approximated the clean break with violence captured by a noted US Signals Corp seismograph, which showed the sound of artillery until 11 am on 11 November, followed by an unbroken line of silence thereafter. If it had been an electro-cardiograph of the war, we could conclude justly that the First World War had died precisely then.

History is messier than that. War didn’t die and violence didn’t stop. The war on the Western Front between Germany and the combined forces of Britain, France, Australia, the United States and others was over – but everywhere else, fighting continued in many different forms. International war bled into civil war, indistinguishable from revolutionary and counter-revolutionary conflicts. New nations fought against old nations and against other new nations. Poland fought Bolshevik Russia, and both fought Ukrainian nationalists. Baltic nationalists fought Bolsheviks and each other. Finns engaged in a nasty civil war, and armed groups roamed throughout eastern and southern Europe with impunity.

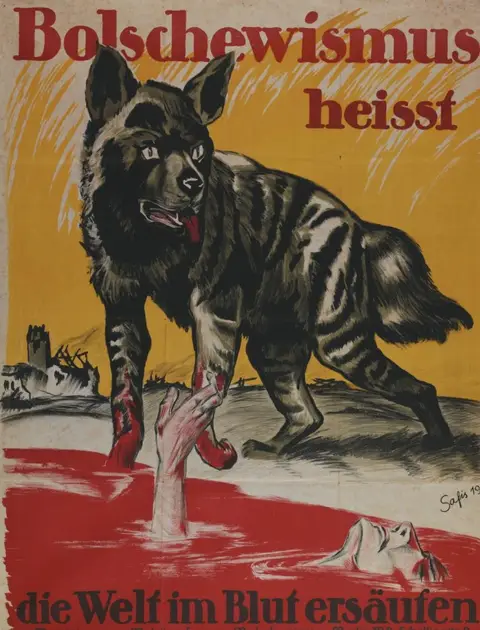

German anti-Bolshevik propaganda poster from 1919 warns: “Bolshevism means drowning the world in blood”.

Why was there that explosion of post–11 November violence? Because the collapse of the German empire was only one of a number of such disasters to beset the old imperial order. The abdication of the Tsar in 1917, and the decision of the moderate Russian provisional government which replaced him to continue to fight on the allied side, created a power vacuum filled by the Bolsheviks, who took power in late 1917. Lenin took Russia out of the international war so that he could consolidate power in the face of armed opposition from many sides. In 1919, the allies, led by Winston Churchill, took a half-hearted decision to help overthrow the communist government by injecting troops from Britain (including some 200 Australian volunteers), France, Greece, and the United States into the fighting. They were joined by Czech troops already there. Their presence in Russia helped galvanise local support for the Bolsheviks, and did nothing to save the disorganised and corrupt White armies from defeat. So after November 1918, when peace supposedly had broken out, on the Russian front a hot war was fought and lost by an anti-communist coalition including the United States, leading by 1924 to the recognition of the Soviet Union by Britain, France, Germany and Italy – American recognition came nine years later – and the start of a cold war which continued until 1991.

The Russian front was on fire after November 1918, but it was not the only front still marked by massive violence. The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire led to the formation of new states in Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland. In each of these countries there was the threat of a communist seizure of power. In Hungary, communist Bela Kun’s seizure of power in Budapest led to a Red Terror, followed by a White Terror when his short-lived regime was overthrown. In Austria and Czechoslovakia, centrist elements prevailed. In Poland and the Ukraine, nationalists attacked Jews, who were supposedly allied with their enemies. Jews who had been uprooted during the war faced even worse conditions after November 1918. The mixture of anti-Bolshevik, extreme nationalist, and anti-Semitic attitudes created a potent, toxic brew out of which fascist movements emerged in the early 1920s. The Nazis were but one start-up party which emerged not during the war, but in its aftermath.

The Ottoman front

The Ottoman front after the war was the site of ongoing and extensive warfare as well. After the occupation of Constantinople, the old regime signed a peace treaty that effectively partitioned Anatolia into colonial holdings under the control of British, French, Italian, and Greek forces, the last of which engaged in brutal treatment of Muslims in Western Anatolia. In response to the partition of their country and the maltreatment of Muslims, a new military force arose which overturned both the peace and the old Ottoman order. Mustafa Kemal, the hero of Ottoman resistance on Gallipoli in 1915, created a new Turkish army that defeated the invading forces, and in the process brutalised and dispossessed Christian civilians whose ancestors had lived in Anatolia for a thousand years or more. The end of this period of ethnic cleansing was the burning down in 1922 of the Christian city of Smyrna on the west coast of Anatolia, and its reconstruction as the Muslim city of Izmir. A new peace treaty was signed by Kemal (later known as Ataturk) and the allies, reflecting the new facts on the ground; this created the dangerous precedent of the recognition in international law of ethnic cleansing, euphemistically termed “population exchange”.

Ataturk’s victory heralded a new era in the history of Turkey. He modernised the language and urged his fellow Turks to follow the lead of the West. To ensure that he alone held power, he ended the Caliphate, which had made the Sultan the symbolic head of Sunni Islam. To many devout Muslims, the end of the Caliphate ushered in a crisis in Islam itself. Who was there to guard the sacred sites of Islam, who was there to uphold the Muslim moral and political order? In this vacuum, a number of devout Muslim groups emerged. Among them was the Muslim Brotherhood, founded in Cairo in 1928, which became the theological and spiritual inspiration of a number of anti-Western groups, including Al-Queda.

The Middle East and beyond

At the same time, the allied carve-up of the Middle East produced violence on the local level, which has also spanned the century following the so-called peace of 1918. A revolt in Egypt in 1919 followed the refusal of the allies to allow a local leader, Saad Zaghloul, to present Egypt’s demand for independence to the Paris peace conference. He was arrested and imprisoned on Malta and later on the Seychelles islands. When freed, he returned to Egypt and continued the struggle for independence, which finally succeeded in 1952. Riots in Palestine in 1919 anticipated the chronic violence attending the conflict between Zionist and Palestinian Arab political groups which a century later refuses to go away.

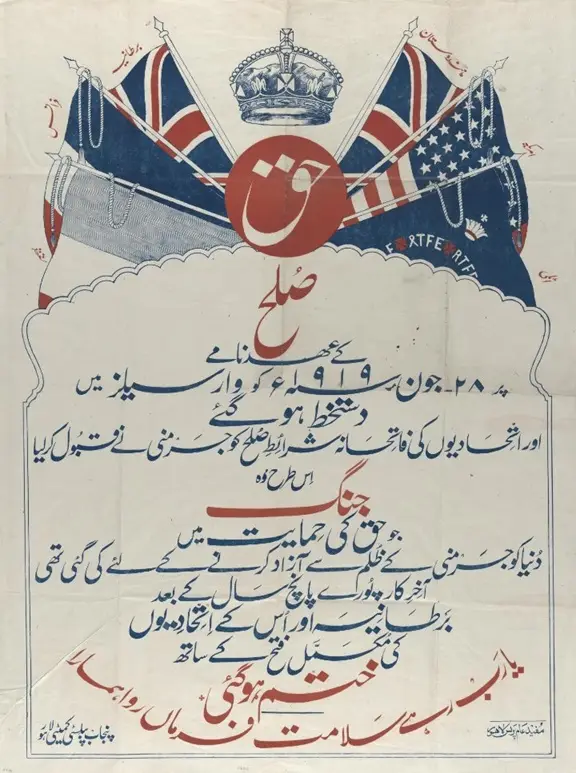

Further afield, the anti-colonial struggle entered a new phase in 1919. In India, hundreds of peaceful demonstrators were massacred in the city of Amritsar, turning those (including Gandhi) who had supported the British war effort in the First World War into a force which over time pushed the British into contemplating what until then had been unthinkable – leaving India to the Indians. That too came after the Second World War, but was foreshadowed right after the Armistice of 1918.

Indian poster showing victorious allies’ flags surmounted by the crown of the British monarch, George V, who was also Emperor of India. The text brings news that Germany has surrendered.

Wilson’s impact in Asia

Wilson’s message mattered in China too. The country had been in the midst of a civil war in 1914–18 and could not match the naval contribution Japan had made to the allied cause. Consequently, when the allies met at Versailles to distribute the colonial or quasi-colonial holdings of the old German empire, including the province of Shandung, south of Beijing, they considered the Japanese case to be stronger than the Chinese case. At least temporarily, Shandung came under Japanese rule. No matter that 150,000 Chinese labourers had been sent from Shandung to dig trenches in France, no matter that Shandung was the birthplace of Confucius: rewarding Japan for its contribution to the allied victory came first. When the news reached Beijing of this decision on 4 May 1919, students burned down the telegraph office, rioted, and organised a new movement named for the day of the riots – the 4th of May movement – out of which emerged the Chinese Communist party.

These events in India, Korea, and China signalled one of the paradoxes of the peace of 1918. On the one hand, the allies won the war because they were able to marshal their imperial armies and resources, and consequently, in a war of endurance, the Central Powers ran out of men and materiel first. In this sense, the Great War was the apogee of empire. But the war was also the beginning of the end of empire, in part because it economically weakened Britain and France, who were unable over time to reconstruct their societies at home and to consolidate their imperial holdings abroad. The mandate system of the new League of Nations, established by the peace treaty, envisioned freedom for colonies over time. How much time was a matter of dispute, but once Woodrow Wilson’s message of self-determination of peoples was linked to the allied victory and to the new League that Wilson created, then the days of empire were numbered.

A member of the 1st Australian Wireless Signal Squadron looks over Bombay (Mumbai), India, December 1919. British mistreatment of Indians after the First World War spurred the movement for Indian independence.

The American perspective

This global tracery of violence was not visible in the United States when the American Expeditionary force came home. The First World War became a short-term memory, one of victory, purchased by American bravery and muscle over roughly one year of combat. Fortunately, only 50,000 American soldiers died in combat; 50,000 more died of the influenza epidemic of 1918–19. This statement does not for a moment diminish the harshness of the struggle against Germany in 1918 leading to the Armistice; but American combat losses in the whole of the First World War were approximately equal to the losses France suffered in August 1914. The US suffered a bloody nose, not a bloodbath. Hence the family memories of soldiers’ sacrifice in 1914–18 paled in comparison with those of either the Civil War or the Second World War.

Industrial warfare did take its toll. When the US Marines took Belleau Wood in June 1918, they did so at a high price – 1,800 killed and another 8,000 wounded, more than the US had suffered at any time since 1865. American forces played a major part in the last allied offensive in September and October 1918 in the Ardennes, and kept up the pressure on retreating German forces until they had to come to terms with their defeat. General John J. Pershing, in command of American forces, was planning a push into Germany for mid-November 1918, but the French generalissimo Ferdinand Foch overruled him.

Joseph Finnemore, The signing of the treaty of peace at Versailles, 28 June 1919 (1919, oil on linen, 165 x 247 cm).

Why did peace fail?

The war on the Western front ended on 11 November with German troops still occupying French and Belgian territory. They returned home as an army, and were saluted as if they had been undefeated by the new provisional government in Berlin. The truth was otherwise. The German army had been beaten decisively in the field, and with the collapse of her allies in September and October 1918, Germany could not continue the war. But the timing and the terms of the Armistice created the material out of which an entirely false narrative emerged – that Germany had been undefeated but betrayed by the “November criminals”: Jews, socialists, and other traitors at home.

It is hardly surprising that in Mein Kampf, Hitler’s war book, he said that he decided to start his political career on the day the war ended on the Western Front. In one sense he was right. The Armistice was not the harbinger of peace we have taken it to be for a century. It was a ceasefire leading to a botched peace settlement and to continuing violence in eastern and southern Europe and beyond.

Armistice Day celebrations in Sydney, 11 November 1918. But the ensuing years brought conflict for many people around the world.

Why did the peace fail? In part it was because those who made the peace paid too much attention to the end of hostilities in France and Belgium, and too little attention to the wildfire raging everywhere else. And in part it was because those who made the peace in 1919 did not recognise that the war could make the world safe for democracy if and only if it was underwritten by economic stability. By punishing Germany through reparations, the peacemakers provided the war-makers to come with all the ammunition they needed.

In 1945, recognising that the surrender of Germany did not signal peace, the Allies started a massive program to rebuild Europe economically, and thereby to undergird the new democratic order of the post-war years. The man whose name is associated with this program, General George C. Marshall, had served as a key planner of American military operations in France in 1918. In 1945 he knew what it would take to avoid a repetition of the short-sighted vision of 1918 which prematurely had declared that victory was ours, and that peace was at hand on 11 November 1918. Making a real peace took more than stopping the guns on one front. Marshall saw beyond the signal-corps seismograph which misled so many others at the time. He lived to see a kind of peace that had evaded the victors of 1918, a peace that lasts.