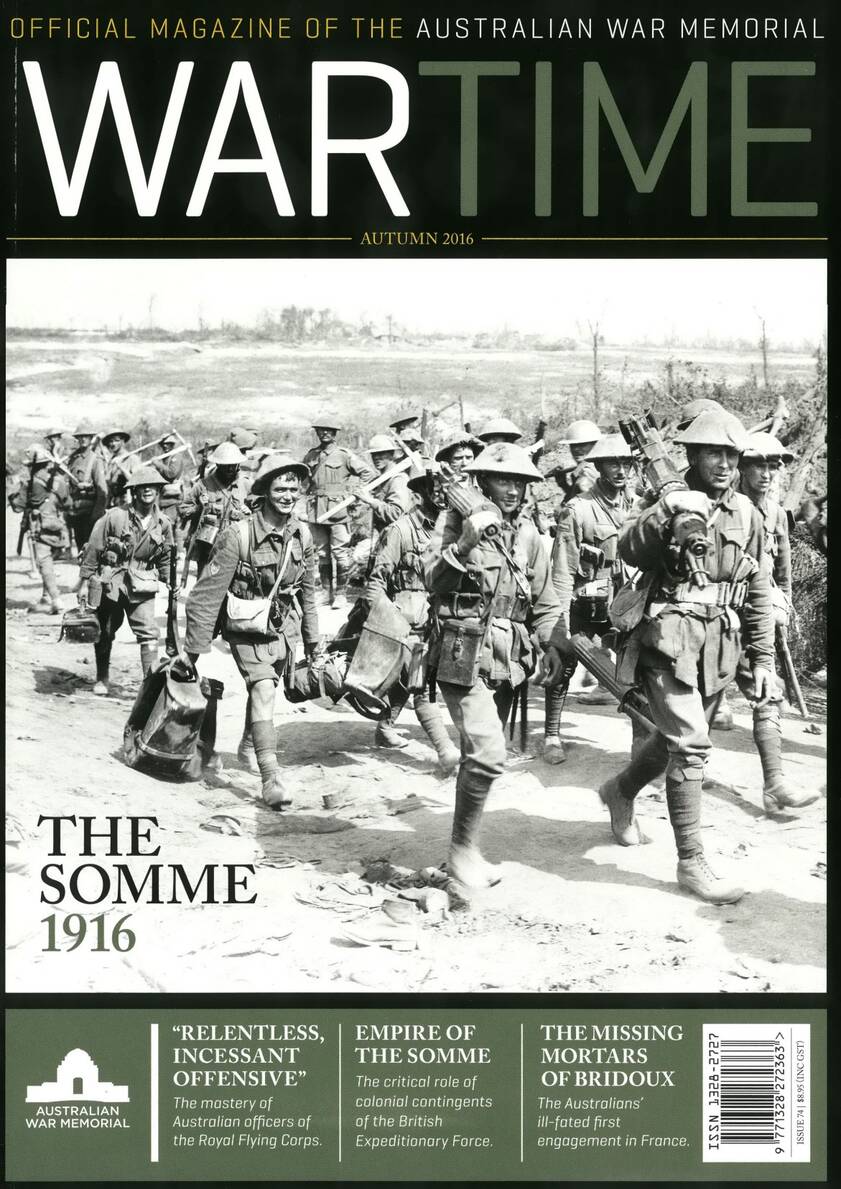

Mud and mortality on the Western Front.

The veterans of the Western Front who were interviewed on audio tape between 1970 and 1990 had many shared memories, such as the infamous mud and the bitter cold and wet of the 1916 winter. But on other aspects of the war – such as fear of death, or the dead themselves – their experiences and opinions diverge.

Artillery driver Edward Eastham did not reach France till late November 1916, so he did not take part in the battles around Pozières where so many were lost. He was assigned a specific duty:

"Pulling men out of mud. We had to pull them out as much as we could. The mud used to hold them in and some of them would disappear in the mud. Oh, anybody who was on the Somme will tell you that. It was terrible."

Driver Edward D. Eastham recalls his time at the Somme

We were off the horses and we were up to our ankles in mud. That was our first impression of France. And the Somme was bad.

It was very bad.

What sort of things, what sort of duties were you doing on the Somme? Pulling men out of the mud.

Was that an assigned duty or? Yes.

It was? Yes, we had to pull them out as much as we could. We had to give it up. Some of the units, the men who got hurt, pulled them out. We pulled them out of the mud.

So the men pulling them out were getting hurt? Yes. Was that because the mud was? The mud just held them in.

Then some of them disappear in the mud. Anybody who was on the Somme would tell you that. It was terrible.

[partial] oral recording of Driver Edward D. Eastham, 8 July 1994 AWM S02040

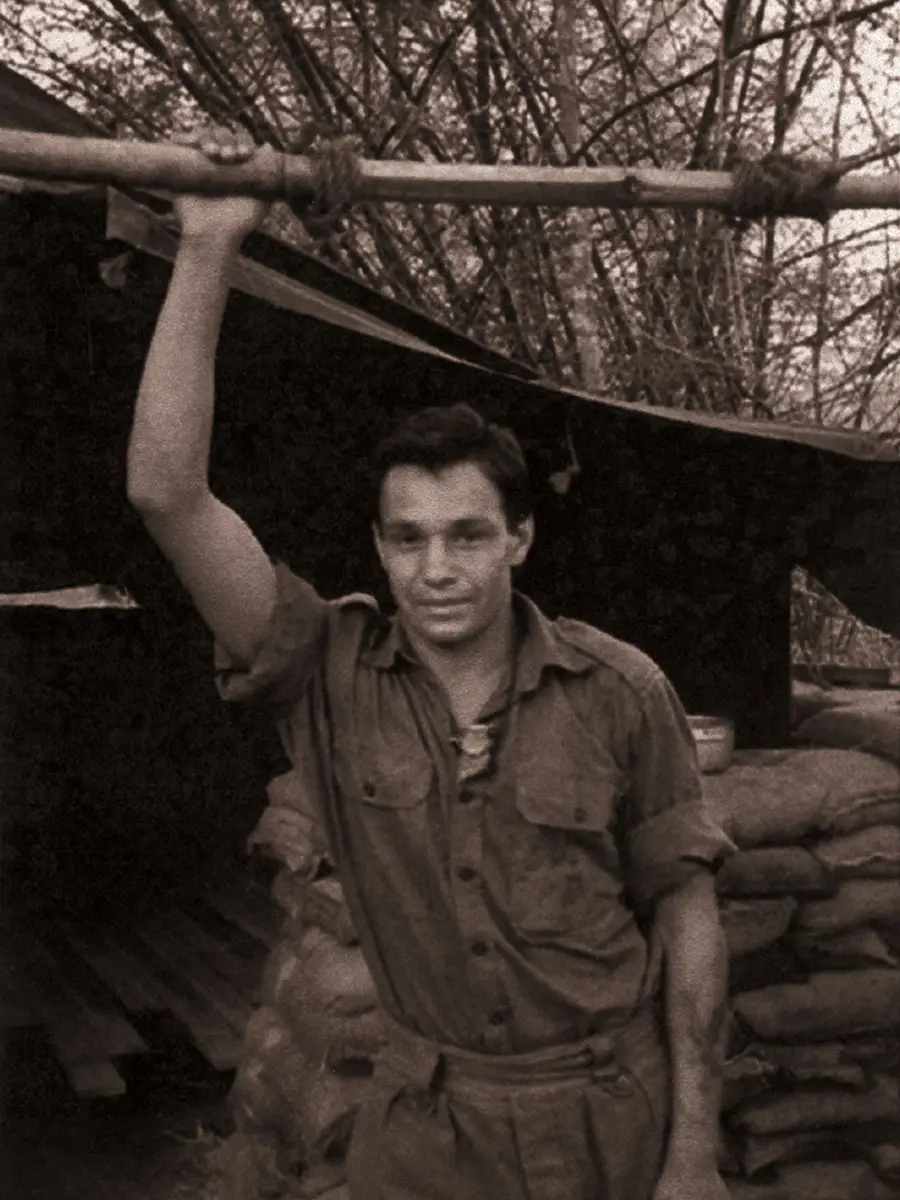

Two unidentified Australian soldiers outside their shelter in the ruins of a Somme village.

Indeed, mud could smother and sink any number of the living, wounded and dead; perversely, it might also do the opposite. As Private Arthur Donne, part of a group on its way to relieve the Irish Guard, recalls:

"I can see him today, a little Irish soldier ... he was standing upright, in the mud, dead, but he couldn’t fall over, the mud was so thick."

Arthur Donne's memories of the Somme

The mud was that deep and we were going through the trenches to get into the front line.

I recall, I can see him today, a little Irish soldier… He was standing upright, in the mud. Dead, as he couldn't fall, he couldn't fall over. The mud was so thick.

They realised that there were more people being injured, by going through this mud than they'd been killed if they were going over land.

So, they decided then that they would lay duckboards from ten miles or fifteen miles back, to the front line.

These duckboards would be about six feet in length, and two feet thick wide, and they'd just lie flat on the mud, and your feet would be walking, so if you got off the duckboard, you went into the mud.

[partial] oral recording of Arthur Donne, 1977 AWM S01902

The sight of dead and partially buried soldiers was a daily commonplace; unburied corpses acquired a kind of utility in the daily routine. Thomas Brain, a private in the 60th Battalion, recalls:

“Going through the communication trench up to the front line, there was a hand sticking out the side of the trench. Some of the blokes used to, as they were going past, shake hands with him. In another part of the front line there was a British Tommy standing over the parapet, leaning up with his rifle there and his leg was sticking out. Like, out, straight. And we used to take it in turns to sit on his leg to have our meals.”

An artillery horse, used for transporting ammunition to the guns, and its Australian driver on a duckboard track between Mametz and Montauban.

Thomas Brain discusses conditions at the Somme

We're trying to go to sleep, and the water's dripping down on top of us from the shell holes.

We were wet. We're in damp and wet clothing all the time.

Night time had come and we'd go out doing whatever duties had to be done, repairing barbed wire, and digging trenches, and ration fatigue, and all sorts of duties that had to be done under cover of darkness.

And we were there for two and a half months.

[partial] oral recording of Thomas Ralph Brain, 1 March 1992 AWM S02096

Brain recalls his mate George Ramsay, who was crouching beside him on the front line. George suddenly fell against Brain, who said: “Get up – you had your breakfast this morning!” But George just toppled over. “I had a look at him,” recalls Brain.

“All his back and through to his stomach was all gone. He was my mate. Whatever we had, we shared.”

It’s not surprising that some might seek to escape the war, even at the expense of their health. Arthur Donne recalls an incident of strategic self-inflicted injury, carried out by another man in his battalion:

“He got a hypodermic syringe and he used to inject his own knee with petrol. The knee would swell and gave you all the symptoms of synovitis of the knee. Later on, they became wise to that and it became an offence to be in possession of a syringe.”

Another defence against the cold was rum, recalls Arthur Donne:

“The winter of 1916 was looked upon, up to that stage, as the coldest winter for 40 years. The rum issue given to the Australian soldiers, they used to get it every night, and you would drink the rum as a medicine. It was given to you in – probably a couple of tablespoonfuls.”

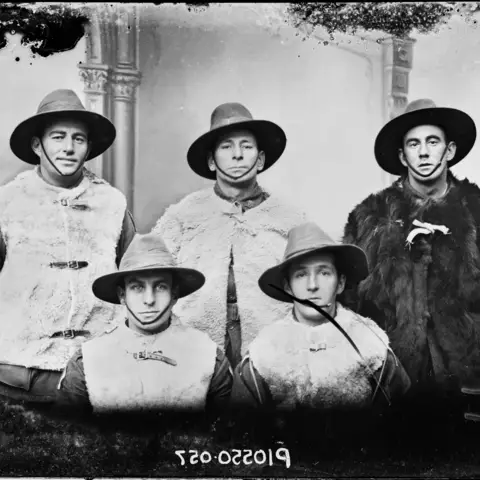

A group portrait of five unidentified members of the 60th Battalion wearing sheepskin vests in what was one of the coldest winters in decades in France.

A member of the 39th Battalion cutting a piece of bread for his midday meal while in the front-line trenches.

Rations, whether of rum or of food, were all too often in short supply. Veterans set great store by the concept of sharing, which created a natural bond between those who shared. Private William Hunt Smith of the 6th Battalion:

“Your food came round and it was only a little loaf of bread and there’s eight of us. You just cut a slice of it each, that’s your day’s ration – the same if you’re getting soup.”

“There was some wonderful chaps, you know … the cream of Australia … and all those boys, they were just like brothers in wartime.”

If these veterans’ feelings towards their old comrades stayed warm over the years, other memories, if not so warm, were just as lasting. Arthur Donne observed that one “became a fatalist – ‘what will be, will be’. You never thought that you would come back. But that was your job, and you did it. That’s the way I looked at it.”

But he also revealed that he had experienced violent nightmares for 30 years after the war. The interviewer asks, “Didn’t you think the cost of war was too high?” Arthur replies: “Oh, no, we didn’t. War – now that it’s over, I’m thankful for the experience. It toughened you up. I don’t really know of anybody that went away that regretted it. It’s in the past and done with.”