Soldiers of 1RAR in Korea learned how to cope under extremely adverse conditions.

As heavy rain battered 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) on 27 July 1952, the dirt turned to mud and slowly but surely bunkers began to collapse. In his bunker, hastily dug into the side of a hill in Korea, Private Edward Charles Kendrick was asleep when it collapsed, suffocating and killing him. His was just one of 58 bunkers that caved in over two days, while a further 26 were condemned as unsafe.

1RAR had arrived in Korea the previous month, the second Australian regiment deployed to join the Korean War. 3RAR had already made a name for itself in Korea, serving in the battles of Kapyong and Maryang San in the early phase of the war. 2RAR, which would replace 1RAR in early 1953, would go on to fight in the final battle of the Hook as the truce neared. 1RAR, however, never served in a major battle. The battalion’s most significant actions were the company raids Operation Blaze in July 1952 and Operation Fauna in December 1952, neither of which were successes for the allied forces.

1RAR’s twelve-month deployment took place wholly within the static phase of the war, which was characterised by patrols, a lack of movement, and the frustration of not making progress as negotiations between the two sides inched agonisingly slowly towards a truce. 1RAR nevertheless suffered significantly, with 43 deaths and more than 150 men wounded by the end of its tour.

1RAR has not often received much recognition in histories of the Korean War. However, the conditions faced by the battalion, and how they coped with these conditions, reveal much about the importance of strong leadership, camaraderie, and a good sense of humour.

Duties in the line

1RAR’s experience of the Korean War was shaped particularly the freezing weather and the frustrations of static warfare. While the Australian soldiers were accustomed to hot summer temperatures, heavy rain and winter snow proved more of a logistical challenge. The relentless rain in July 1952 led to the collapse of the bunker that killed Private Kendrick, but snow and freezing temperatures could be just as trying. Private Des Guilfoyle later described how “even the ground was frozen solid and rivers iced up whilst a bone-chilling variable wind swept over the barren landscape.”

The cold created significant operational problems. The soldiers, for instance, had to sleep with their weapons to prevent them freezing up, while standing patrols had to be rotated regularly to avoid the risk of freezing to death. Keith Payne, who was later awarded a Victoria Cross in Vietnam, recalled how, on returning from Operation Fauna in December 1952, the hill was like a “slippery, sliding ice rink” that turned into mud. It was hard to gain footholds, and many men tore their hands on the barbed wire as they tried to pull themselves up the hill. Considering the entirety of his wartime experiences, including Vietnam, Payne concluded that “Korea would be the war with the worst climatic conditions – worst conditions, anti-human comfort – that a soldier could ever put up with.”

By the time 1RAR arrived in Korea, the static phase of the war had begun, with each side making limited attempts to push the other back, with little success. 1RAR’s two company raids, for instance, aimed to capture neighbouring hills and prisoners, but failed to meet their objectives. However, these types of raids were relatively rare, and life in the line was instead centred around a heavy program of patrols in no man’s land. While the type and number of patrols varied, an ordinary night in the line might see one to six fighting patrols, one or two ambush patrols and a further two or three reconnaissance patrols heading out into the area between the two sides. Eight to ten standing patrols, meanwhile, would keep watch for the enemy patrols which were also out in no man’s land each night. More occasionally, patrols known as lay-up patrols would sneak behind enemy lines to gather intelligence, staying for as long as several days.

Capturing prisoners was the goal of many of the patrols. As the months passed without a single prisoner being taken, however, it became increasingly apparent that this objective was pointless. Brigadier Thomas Daly, who led the 28th British Commonwealth Infantry Brigade, of which 1RAR was a part, later called the focus on capturing prisoners through patrols “a disaster” and “uneconomic”. Frustration about the lack of progress inevitably grew over time. Lieutenant Douglas Yeats later wrote that “weeks of constant patrol duty became a weary business, as men spent tense hours, exposed and vulnerable, without seemingly achieving any results.” Given the static nature of the war, however, patrols were considered the only way to maintain pressure on the enemy, and remained the primary tactic during this phase of the war.

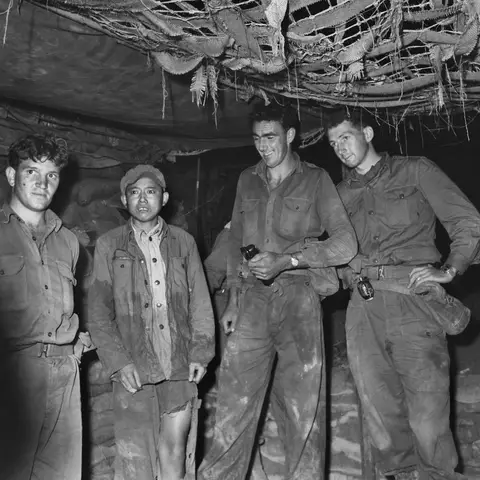

Men of 1RAR with a captured Chinese soldier in the Songgok area, September 1952. Left to right: Cpl Ronald McCrindle, unidentified Chinese POW, L/Cpl David McCarthy, and Lt Peter Cliff, who was killed while leading a patrol later that month. Photograph D.H. Lee. AWM

Five unidentified members of 9 Platoon, C Coy, 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian (1RAR), crouch AWM

On 13 September 1952, 1RAR finally took its first and only prisoner. Lieutenant Peter Cliff, who would be killed in action later that month, was leading a routine fighting patrol when they encountered an enemy patrol at around 0200 hours. A firefight broke out, during which two members of 1RAR were killed. It was during the fighting that Lance Corporal David McCarthy stumbled upon a Chinese soldier who had become separated from his unit and seized him. But no useful information was gained from the prisoner, proving Brigadier Daly’s point about patrols and prisoners. When the prisoner was interrogated, he was only able to describe the immediate goals of his patrol: to find and bring back two UN landmines, destroy other mines, and if possible, capture a prisoner.

Patrols were not only frustrating and repetitive; they also risked the safety of the Australians. On 23 August 1952, Captain Phillip Greville and Private Dennis Condon were taken prisoner by a Chinese patrol. They had been part of a group sent out to repair a minefield fence, and on the return journey they were ambushed, with Greville and Condon taken by “snatch parties”. Both suffered harsh treatment in Chinese prisoner-of-war camps and were only released after the truce the following August.

Patrols were not only frustrating and repetitive; they also risked the safety of the Australians. On 23 August 1952, Captain Phillip Greville and Private Dennis Condon were taken prisoner by a Chinese patrol. They had been part of a group sent out to repair a minefield fence, and on the return journey they were ambushed, with Greville and Condon taken by “snatch parties”. Both suffered harsh treatment in Chinese prisoner-of-war camps and were only released after the truce the following August.

Even back among the bunkers, the Australians were not safe. Artillery and mortar fire were relentless for soldiers in the line. Official historian Robert O’Neill estimated that between June 1952 and February 1953 an average of 125 enemy shells and 66 mortar bombs fell on the 28th Brigade each day. In November 1952, 1RAR recorded 28 shells, 123 mortar bombs and 296 “unspecified projectiles” in battalion areas in a 24-hour period. The constant bombardment caused numerous casualties. The accompanying sense of danger and the constant noise put many men on edge. Guilfoyle remembered how one soldier broke under the strain, crawling into an ammunition bay and refusing to leave, having to be dragged out by his comrades. Guilfoyle was sympathetic, saying that most of them experienced similar feelings, confessing that “boy, it was mighty hard on the nerves.”

Coping in the line

Unidentified members of 9 Platoon, C Coy, 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian (1RAR), on patrol

Despite the difficulty of the conditions, accounts at the time and afterward emphasised how well the members of 1RAR coped with life in the line.

After Private Kendrick was killed during the rains of July 1952, the war diary noted that “morale remains high and the men are displaying excellent spirit under extremely adverse conditions.”

Staff Sergeant John Samuel Beam, who transferred from 3RAR to 1RAR in April 1952 later discussed how 1RAR “lived like moles under the ground” but “even then, morale was good, that’s what amazed me.” Corporal Norman Goldspink similarly recalled that “morale was great, everyone was a volunteer, did what they were asked and looked forward to leave.”

Disciplinary records also indicate that the members of 1RAR appear to have been in a stable psychological state. In February 1953, for instance, while 1RAR was in reserve, members of the unit made up just three of the 13 Australian soldiers who appeared in provost records.

What was it that helped the members of 1RAR cope with the difficulty of life in the line? Strong leadership within the Australian army was particularly crucial. In 1951, Major General James Cassels, leader of the 1st Commonwealth Division, was informed by the Australian government that he could appeal decisions made by the American and UN leadership. Although Cassels never needed to submit a formal appeal, this instruction gave him leverage in dealing with Australia’s allies. For example, when Cassels was directed to escalate patrol efforts in order to capture a prisoner every three days, he was in a position to refuse.1RAR’s first commanding officer in Korea, Lieutenant-Colonel Ian Hutchison, also rejected pressure from the widely disliked British Brigadier John MacDonald to “get [his] battalion bloodied” by launching a battalion-sized raid when the unit first arrived in Korea. After Hutchison resisted this idea, it was downgraded to a company raid, Operation Blaze, in July 1952. Both Hutchison and Cassels were determined not to waste lives, a possibility all the more likely during the static period as it became clear that neither side would make significant progress.

Men of B Coy, 1RAR, constructing a new dugout, Korea, September 1952. Photograph P.O. Hobson. AWM

1RAR also benefited from the fact that the army leadership had learned the lessons of previous conflicts and the earlier part of the Korean War. As a result, 1RAR was well-equipped and rotated regularly with other brigades so that the battalion had regular periods behind the line. Even better were the leave arrangements. After four months of service, members of 1RAR were entitled to five days of leave in Japan, with 21 days granted after eight months. This meant that there was always something to look forward to, either leave or a break from being in the line. Camaraderie and a sense of shared identity were equally important in maintaining high spirits. 3RAR, the first Australian unit deployed to Korea, served throughout the entirety of the conflict. This meant that individual men were rotated out when their tours ended. 1RAR, however, was sent to Korea for twelve months only. This meant that almost all of its members trained together, fought together, and went on leave together, enabling the formation of strong friendships. Staff Sergeant John Beam later reflected on how this camaraderie contributed to the psychological wellbeing of the soldiers, saying that they never felt “isolated” or “abandoned”; instead “we developed, through being with all these guys together, having confidence in each other, having come out of so many similar situations previously.”

1RAR’s identity also developed in opposition to other units. Looking around them, the members of 1RAR found that they were more disciplined than others. This was particularly obvious when the battalion replaced 1 Royal Canadian Regiment (1RCR) at Hill 355, known as Little Gibraltar, on 1 November 1952. The official handover notice, signed by the commanding officers of both units, stated that 1RCR had left the position “complete, slightly worse for wear and tear, but otherwise defendable”. This was putting it generously. The Australians found that the Canadians had not disposed of their rubbish properly, leaving empty cans and containers outside their bunkers in view of the enemy. Commanding Officer Lieutenant-Colonel Maurice “Bunny” Austin, who had taken over from Hutchison in October 1952, was frustrated by this behaviour, later saying that it was a “barely organized rubbish heap” and that the Canadians had “simply chucked everything over the fence in front of their positions.”

Far worse, the Canadians had failed to record and mark all their minefields. This led to a number of incidents, including the patrol in which William “Digger” James lost his foot. 1RCR had also been lax in their patrols, meaning that the Chinese forces had the upper hand in no man’s land. 1RAR had to undertake an intensive patrolling program to regain some control, which inevitably led to further casualties. The only benefit of 1RCR’s laxity was that it helped to develop 1RAR’s pride and camaraderie, as the Australians could compare themselves favourably to their Canadian counterparts. By mid-November the unit diary approvingly noted that “the [general] appearance and layout” of the defences were “resuming normal standards [maintained] by 1RAR”.

Santa Claus (WO2 Richard McLaughlin, CSM A Coy) with LtCol M. Austin, commanding officer, 1RAR, 1 January 1953. The battalion celebrated Christmas late because it had been in the line on the day. Photograph P.O. Hobson. AWM HOBJ3900

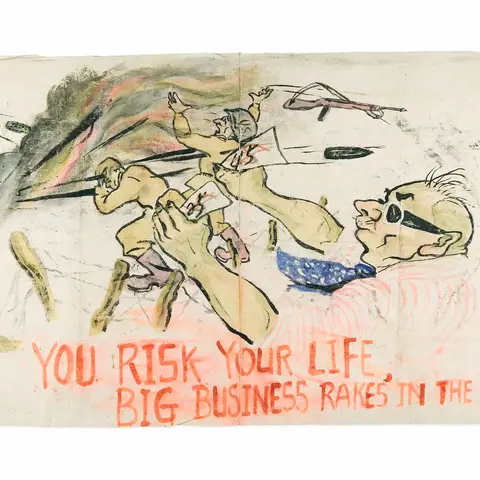

By Christmas 1952, 1RAR was nearing the end of its service in frontline areas. As temperatures plummeted and the war wore on, the soldiers were looking for moments of levity to relieve the pressures of life in the line. After the experiences of previous years, 1RAR’s leaders were anticipating that Chinese propaganda would appear on the wire, as a kind of perverse Christmas gift. Enemy propaganda was a regular part of life, both in loudspeaker broadcasts and the arrival of paper cartoons with messages encouraging surrender and telling the Australians that their families were suffering without them. As Christmas neared, 1RAR organised extra patrols to deter Chinese “Xmas cheer” patrols. Nevertheless, Chinese propaganda appeared on 1RAR’s minefield fences on the night of 23 December. Along with banners and cards carrying propaganda, the Chinese soldiers also left watches, cigarettes, sweets, and safe conduct passes to encourage defection.

Stainless steel cigarette lighter with flip top lid. An enamelled crest is attached to the front of the lighter and depicts a King's Crown above a scroll with the word 'COMMONWEALTH'. The front of the lid is engraved with 'KOREA 1952-1953' and the back with 'A COY 1 RAR SGT. J. H. WELCH'.

Rectangular calico banner painted in poster paint with two United States soldiers facing explosions and Chinese bullets within wire entanglements. To the right a figure of Uncle Sam dressed in a red and white striped shirt and star spangled tie, holds two fistfuls of dollar notes. Beneath, in red letters, is 'YOU RISK YOUR LIFE, BIG BUSINESS RAKES IN THE DOUGH'. The 'SS' in business is written '55'. Two pieces of fabric have been joined down the centre with a simple seam before the banner has been painted.

Whatever the intent of the propaganda and gifts, they were welcomed by the men of 1RAR. As the war diary noted, it had “greater souvenir value to our men than any noticeable psychological effect”. Members of 1RAR remembered the regular propaganda with fondness and many took examples home with them. Private Fred Roberts recalled that “it was so overdone” that it “became a source of amusement and entertainment.”

On Christmas Day, Lieutenant Colonel E. Amy, General Staff Officer for the division, presented Austin with a portrait of Marilyn Monroe. The unit war diary noted the effect on the recipients, saying “the portrait of Miss Monroe serves to remind them that the desire which her lovely form engenders in many masculine minds is equalled, if not exceeded, by the desire of members of this unit to capture a PW [prisoner] on one of our many patrols designed for that purpose.” The ability to see humour in their situation allowed members of 1RAR to maintain high spirits throughout their 1952–3 tour in Korea. 1RAR departed for Australia aboard the troopship New Australia in March 1953, after a series of farewell parties and ceremonies. Before leaving, the unit visited the United Nations war cemetery in Pusan to pay their respects to those who would not be making the voyage home. returning to Australia.

C Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) marches through Martin Place prior to embarkation for service in Korea. The officers at the front of the company are 3391 Major Bruce Barrington Hearn (leading the company); 237656 Lieutenant (Lt) John Murray Burke (far left); 237633 Lt Robert James Moran (behind Hearn); and 237657 Lt Peter Henry Cliff (right, at front of column) (killed in action 21 September 1952).