Animals have been associated with the Australian military since seven horses were listed on the first census of 1788.

More than 100 years later, contingents of horsemen bound for the war in South Africa paraded through the streets of nearly every capital city. The Boer War was later described as “undoubtedly the most destructive of horses, no other wars excepted”. Horses were shipped to South Africa to participate in the war from as far as Australia, Britain, the United States, Canada, Hungary, Argentina and India. They were vital to the war effort on both sides, with the conflict ranging widely across the veldt. The horses suffered from exhaustion and disease and were regularly killed by combatants on both sides as a means of capturing the men riding them. One eyewitness described "their skeletons covering the veldt in all directions with a ghastly whiteness".

Perhaps surprisingly, most of the horses of the early Australian contingents were considered to be relatively poor. Australian poet and correspondent A.B. “Banjo” Paterson said that they had “generally failed to act up to expectations.”

Many had been workhorses on the streets of Sydney, and had been worn out by work on paved roads long before sailing for South Africa. “The well-bred Waler,” wrote Paterson, “carries his man till he is fit to drop with fatigue … but not so your big-boned, broad-hipped coacher.” The Assistant Inspector of Remounts, Lieutenant-Colonel Birkbeck, wrote that “generally a good, compact, true-made, big-barrelled horse on short legs, with a certain amount of quality, of whatever nationality … has done well. Except,” he added, “the Argentine, which must have horrible strains of blood in his veins.”

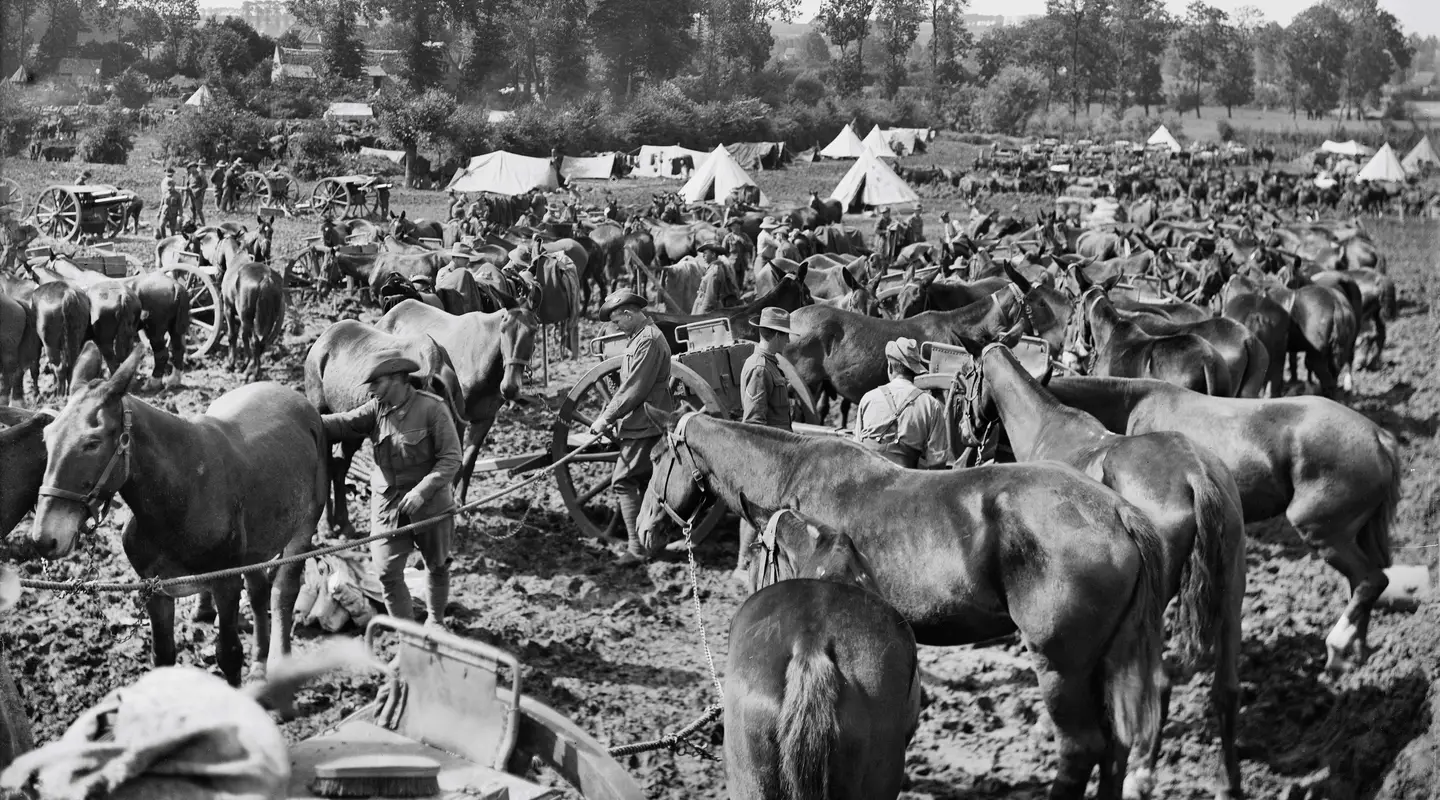

Mounted troopers of the 1st Battalion, Australian Commonwealth Horse, watering their horses while on the march in Transvaal.

Birkbeck’s description fitted the Australian horse type known as the Waler, a hardy stock horse that had been gradually bred to suit harsh Australian conditions. A proper Waler could demonstrate great endurance under the strain of carrying heavy loads long distances, even with a lack of food and water. After the experience of the poor stock during the Boer War, Australian military authorities looked to increase the proportion of Walers among their horses. Several years after the end of the Boer War, Australian military authorities were still defending their mounts. “It’s all rubbish to say that the Australian Horse is lean and spindle-shanked,” said one officer in 1908. “He is as good as ever he was, but the trouble is there are not so many of him.”

On the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the Australian government swiftly committed one light horse brigade to the war effort. It was soon realised that many more men and horses would be needed, and the light horse regiments expanded until the formation of the Anzac Mounted Division in March 1916. The men of the Australian Light Horse brigades famously fought on Gallipoli without their horses but could not do without them during the sweeping battles through the Sinai and Palestine campaigns of 1916–17. Perhaps there is no more iconic battle than the battle of Beersheba, on 31 October 1917, to demonstrate the usefulness of horses in allowing sweeping manoeuvres to cut off the enemy and capture any objective.

But while the romance of the desert campaign is one part of the horse’s story in the First World War, an even greater part was played out on the Western Front. There horses were vital in transport of a different kind, moving the thousands upon thousands of artillery pieces into and out of position all along the front. Called upon to pull thousands of heavy guns and countless limbers of ammunition through all conditions – dust, snow, and most famously, the sucking muddy morass of Belgian Flanders – horses were in constant use throughout the war. If the writer who had lamented the fate of so many horses in the Boer War had known what would happen in the First World War, he would have been shocked. By mid-1917 it was estimated that a quarter of a million horses had died or been killed in various theatres of the war, equal to 16 per cent of a year’s available horse stock.

Horses were in such widespread use during these wars simply because they were the most easily accessible, if not the best, mode of transport available at the time. Animals have long been used to do things for us which we cannot do easily or at all, and war is no different. The armies fighting on both sides of the First World War used not just horses, but mules, donkeys and even camels to get men, munitions and supplies to where they needed to go.

Taking Flight

AUSTRALIA. CAPTAIN MURRAY RELEASING A CARRIER PIGEON FROM AUSTRALIAN ARMY VESSEL AT1434.

Another animal that proved its worth during these conflicts filled another gap in human capability – communication.

On the battlefields of the Western Front, communication was vital but by today’s standards, methods to maintain contact with men fighting at the front were crude. Hundreds of metres of telephone wire could be strung out across the front in preparation for an attack, only to have it smashed once the artillery bombardment began. Men risked their lives to carry one precious message back to a commanding officer. But pigeons were also a valuable means of getting information to the back lines, even under heavy artillery fire.

As many as 20,000 pigeons were killed during the First World War. But despite huge advances in wireless technology in the interwar years, pigeons had a role to play in the Second World War, too. With the threat of a Japanese invasion looming, Australian military authorities had to take seriously the prospect of a war in the tropics. While most communication was conducted with telephone or wireless technology, there were considerable problems with both of these methods north of Australia. Nobody relished the task of dragging drums of telephone wire up and down the Kokoda Trail in the Owen Stanley Ranges, and the humidity in New Guinea and on the islands could seriously interfere with wireless signals.

In response to these problems, senior Australian Army Signals officers turned to pigeons. Trials in early 1942 proved successful, and a call was put out both for experienced owners of homing pigeons to join the military, and for breeders to donate birds. Within the first 12 months of the project, pigeon fanciers of Australia had donated some 13,500 birds, and the Australian Corps of Signals Pigeon Service was developing rapidly – first in Queensland, and from December 1942 in Port Moresby. Pigeons proved so successful in the war in the Pacific that men from the Australian pigeon services helped the American military develop their own program. The pigeons provided a sense of confidence to both infantry and shipping alike, so they were rarely left out of operations, even if other methods of communication worked in the first instance.

Two Australian pigeons performed feats of such bravery in the Pacific that they were awarded the Dickin Medal. This was instituted in 1943 by British charity the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals, and is considered the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

On 5 April 1944, Australian pigeon DD.43.Q.879 was taken into action by an American patrol on Manus Island. The patrol ran into a large party of the enemy, and had to release the pigeons it had carried with them in the desperate hope that their message would get through and they would be rescued. The first two pigeons released were killed in the heavy enemy fire, but DD.43.Q.879 reached headquarters in time for a successful extraction of the patrol to be organised and executed.

On 12 July 1945 Australian pigeon DD.43.T.139 brought back a message from Army Boat 1402, foundering in the Huon Gulf, after flying 40 miles (64 kilometres) from the ship to Madang during a heavy tropical storm. The pigeon arrived in time for a rescue vessel to salvage the stricken ship, rescuing its crew and its cargo of precious stores and ammunition. Both of those birds had been donated by civilians in Melbourne, both of whom were presented with a copy of their bird’s Dickin Medal, while the original went to the military. In modern warfare the problems of transport and communication have been resolved to the point where we no longer need to rely on animals for either activity. But recent and current conflicts pose new problems for which the best answer is still the use of animals.

Blue Bar Cock Pigeon No139: Dickin Medal winner

Blue Chequer Cock Pigeon Q879: Dickin Medal winner

Four legs good

In wars such as the Vietnam War, the enemy moved out of its traditional place across no man’s land and melted into villages, plantations and jungles. Suddenly the problem was simply to locate the enemy accurately. In early 1966 the Australian Army began experimenting with the use of dogs to track escaping enemy. Eleven dogs were rescued from shelters, trained, and then served with Australian forces in Vietnam between April 1967 and September 1971. Named for Roman emperors, the dogs were all black Labradors or Labrador crosses, and proved exceptionally successful at their allotted task, tracking. The dogs worked with a team of five men who included one covering their work, two visual trackers, a machine gunner and a signaller. They were usually inserted into the jungle by helicopter – an experience many of the dogs enjoyed – and then set to work. Only one of the dogs died (from heat exhaustion at Vung Tau), but none would return to Australia. The Australian Army had determined at the outset of the project that due to quarantine requirements, the dogs would have to remain in Vietnam after their service, and was steadfast in refusing applications to bring the dogs back.

Long Green area, South Vietnam. 1967-06. Two tracker dogs with their handlers, of 7th Battalion, The Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR), talking to the Battalion Second in Command, Major David Drabsch. Left to right: Norman Cameron with "Cassius", Major Drabsch, Tom Blackhurst with "Justinian", unknown. Shortly afterwards the dogs tracked a wounded Viet Cong (VC) soldier and were found licking his face.

This raises one of the interesting questions in the use of animals in war. For all intents and purposes, these animals are trained pieces of equipment, bought and paid for in order to fulfil a job. And yet of course their handlers and those who come into contact with them form relationships with them, and struggle to think of them as little more than a piece of kit.

There is a long history of animals being taken to war for morale purposes, alongside these working animals. Many of the contingents to the Boer War took dogs as their mascot. The Third New South Wales Contingent was given a rough collie called Bushie, named by Lieutenant-Governor Frederick Darley, inspected by Premier John See and his cabinet, and formally handed over to Colonel Airey’s orderly in the Chief Justice’s chambers in the Supreme Court. Bushie was considered to be the first dog to be officially sent to war (with emphasis on “officially”), and came to the attention of Queen Victoria, living out his days in England after being wounded in the shoulder.

Nelson, Newfoundland pet dog for the 1st Contingent to the Boer War, lying in front of a bell tent in the Transvaal, two horses in the left distance. His collar has RHA (Royal Horses Artillery) and insignia stamped on it. Nelson was taken with his owner, Private Arthur Edge, with the 1st Contingent in 1899.

The First South Australian Contingent’s St Bernard, Nelson, had a slightly more exciting experience of war. Nelson was a pet of Private Arthur Edge, and earned his position as mascot after making too many friends roaming the contingent’s training ground. Although the men were doubtful they would get permission to take Nelson far, he found himself in the depths of Pretoria, cadging rides on wagons when he felt like a rest. He was captured on several occasions, at one point missing for several months before being liberated from his Boer captor by a South Australian soldier. The Boers valued him, too, offering the soldier £50 for him – an offer that was indignantly refused. Nelson was feted on his return to Adelaide, and retired to tour the state raising funds and showing off by barking loudly when anyone called “Boers, Nelson!”

Leaving the dogs behind in Vietnam was incredibly difficult for their handlers. One, Peter Haran, who worked with Caesar, later wrote, “When I went to Vietnam with Caesar I cursed the day I volunteered to become a tracking dog handler. The day I left him there broke my heart.” Major Leo Van de Kamp also recalled, “I know that many a handler has shed more than one tear for having to leave his dog behind when the unit returned to Australia.” The dogs were not entirely abandoned, but were re-homed with various embassy and consular staff before the Australians left.

"I personally am of the opinion he saved lives that day."

Mark Donaldson

IED dogs

Watercolour of Explosive Detection Dog, Kuga, who served in Afghanistan. One of 10 watercolours by HSC student and artist, Rachael Michelle Potter, in a series entitled 'Unsung Heroes- Afghanistan', of which nine are in the Memorial's collection. Kuga was a combat assault dog who died in 2012 after receiving four gunshot wounds.

Dogs are still in use in the Australian military in operations today. There is still a need for tracker dogs, and their role has also been expanded to locating improvised explosive devices in various theatres of war. Not only are they useful in these roles, but many of the dogs in use are fiercely loyal and brave to a fault.

In October 2018 a Belgian Malinois named Kuga was awarded the Dickin Medal for locating a Taliban ambush across a river, attacking a gunman despite being shot himself several times, and then crawling back into the water and swimming back to his handler while badly wounded.

Kuga’s wounds proved too much, and he died after 12 months’ intensive veterinary treatment. Australian Victoria Cross recipient Mark Donaldson accepted Kuga’s Dickin Medal on his behalf, saying, "I personally am of the opinion he saved lives that day."

That fierce loyalty shown by dogs in war goes both ways. In September 2008, Australian explosives detection dog Sarbi went missing after a joint Australian, American and Afghan convoy was ambushed. She was never forgotten, and rumours of her being with an Afghan family bounced around Australian and American forces.

She was eventually recovered in November 2009, those who used her services in war never giving up hope that she would be returned. She died in Australia, a much-loved family pet, aged 12 in 2015.

Australians have taken (or tried to take) kangaroos, wallabies, kookaburras, possums, koalas, wombats, and all manner of other animals to war. From the kangaroos under the pyramids in the training camps of the First World War, to the dogs and cats smuggled home aboard troopships, animals have been a source of comfort, strength, skill, interest and love to Australian servicemen and women for more than a century. Australia’s National Day for War Animals, commemorated annually on 24 February, is a chance to wear a purple poppy and think about the role animals have played for us. We will remember them, too.

Lines of the Australian 9th and 10th Battalions at Mena Camp, looking towards the Pyramids. The soldier in the foreground is playing with a kangaroo, the regimental mascot. Many Australian units brought kangaroos and other Australian animals with them to Egypt, and some were given to the Cairo Zoological Gardens when the units went to Gallipoli.