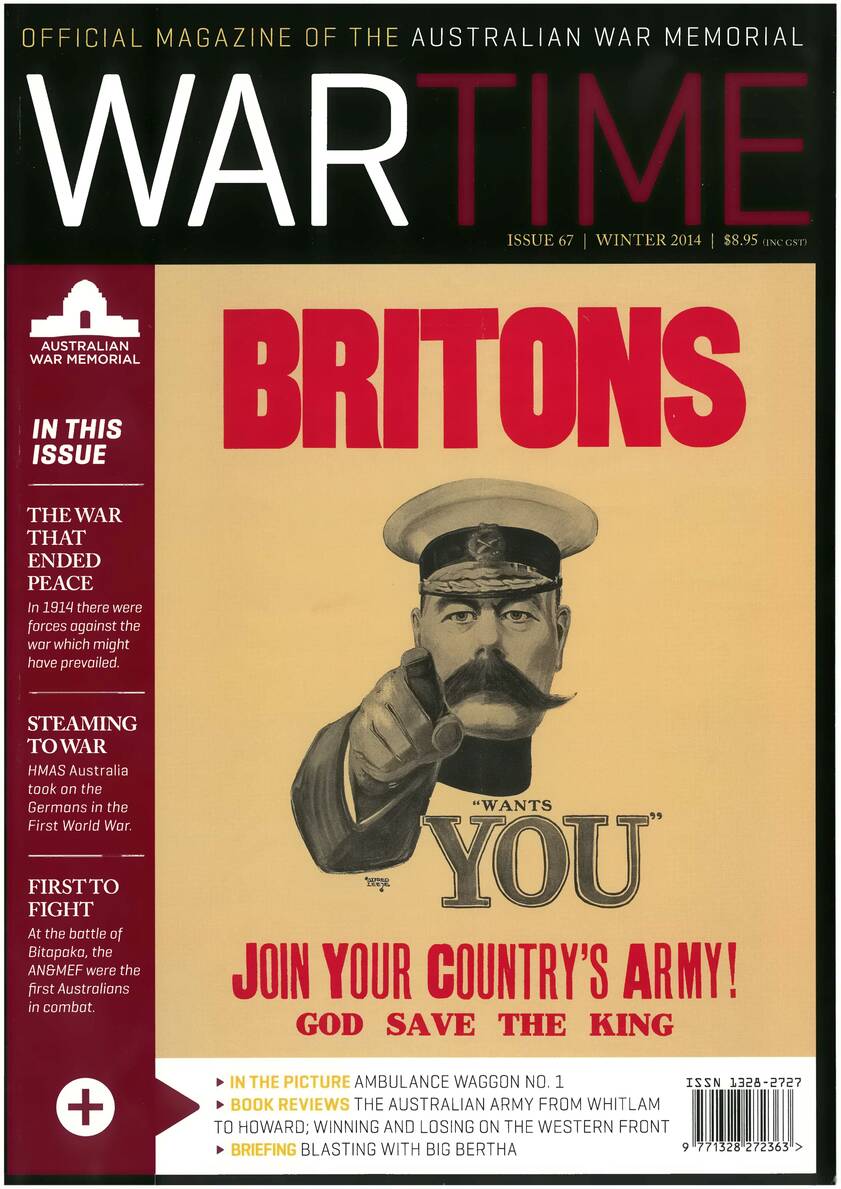

The experience of 1914-18 seen through the eyes of Australian artists

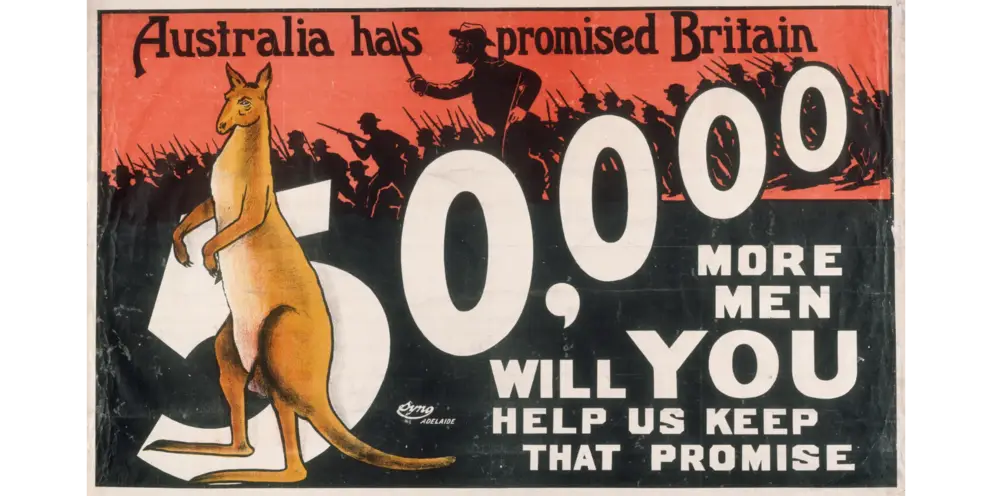

Syno, Australia has promised Britain 50,000 more men (1915), chromolithograph on paper on linen.

War, and the way it can be represented, has long been a preoccupation of artists, who have both reacted to its horrors and responded to the needs of their nations. After the initial surge of volunteers for service in the First World War, in Australia new methods of recruitment were adopted to encourage more men to enlist for the war effort.

By the start of the 20th century, the poster had reached its zenith as a tool for communication. Mass produced and intended for public display, posters played an important role during the First World War in Australia. They could disseminate information as well as create propaganda, and were frequently used to encourage recruitment.

The poster Australia has promised Britain 50,000 more men reflected the initial enthusiasm for the war and the scale of the recruitment required. It appeals directly to a strong sense of patriotism with the image of the kangaroo, and at the same time makes a call to support the Empire.

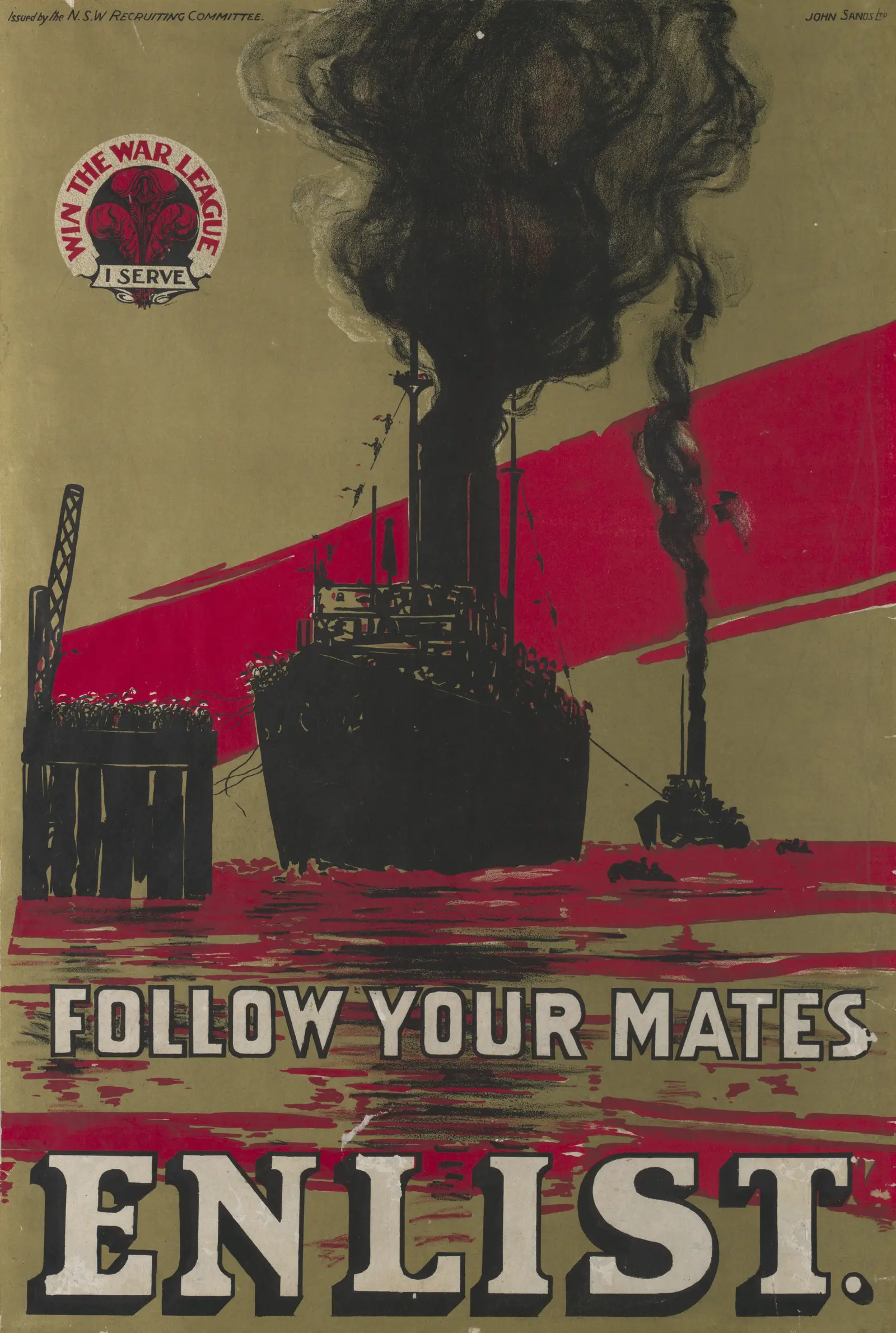

Similarly, Follow your mates: Enlist directly encouraged men to join the navy, appealing to a Boy’s Own sense of adventure and mateship. The poster was unusual, as few recruiting posters featured naval scenes, instead favouring images of Australian troops.

Unknown artist, Follow your mates: Enlist (c. 1914–16), chromolithograph on paper.

In August 1916, Australia established the official war art scheme, based on similar models in Britain and Canada. Fifteen artists were employed under the scheme, with an additional three sculptors assigned to the modelling subsection of the Australian War Records Section, some of whom later helped create the Australian War Memorial’s dioramas.

One of these artists, Wallace Anderson, produced the first sculpture ever acquired for the Memorial’s art collection, Evacuation. A muscular figure leans against a broken gun carriage, his foot resting on a flag.

In many ways this sculpture epitomised the archetypal image of the Australian soldier during the First World War, an ideal in both physique and demeanour. Other artists chose to capture the traits for which Australian soldiers were renowned, including their humour.

Wallace Anderson, Evacuation (1925), bronze.

Will Dyson, The batman (Compree washing madame), 1920, oil on canvas on wood panel.

This informal approach is evident in Will Dyson’s The batman (Compree washing madame), in which a soldier talks with a French woman, asking her if she does washing – ostensibly for his officer, but probably with his own chucked in too.

The war art scheme sent many artists to places in which Australians served, enabling them to experience for themselves the conditions and the atmosphere of such places. Many gained an intimate knowledge of the devastation of the battlefield, while others were interested in capturing the lesser-known landscapes and towns through which Australians often fleetingly passed.

A.H. Fullwood, Chateau at Ham-sur-Heure (1918), watercolour and gouache with charcoal on paper.

Attached to the 5th Division AIF, A.H. Fullwood worked in France between May 1918 and January 1919. His major contribution as a war artist was to record in a straightforwardly picturesque manner those aspects of war which others took for granted. Chateau at Ham-sur-Heure, depicting the AIF headquarters after the Armistice, is rendered in a romantic manner, with the dark walls of the chateau rising up against the dusk in a still, snow-covered landscape.

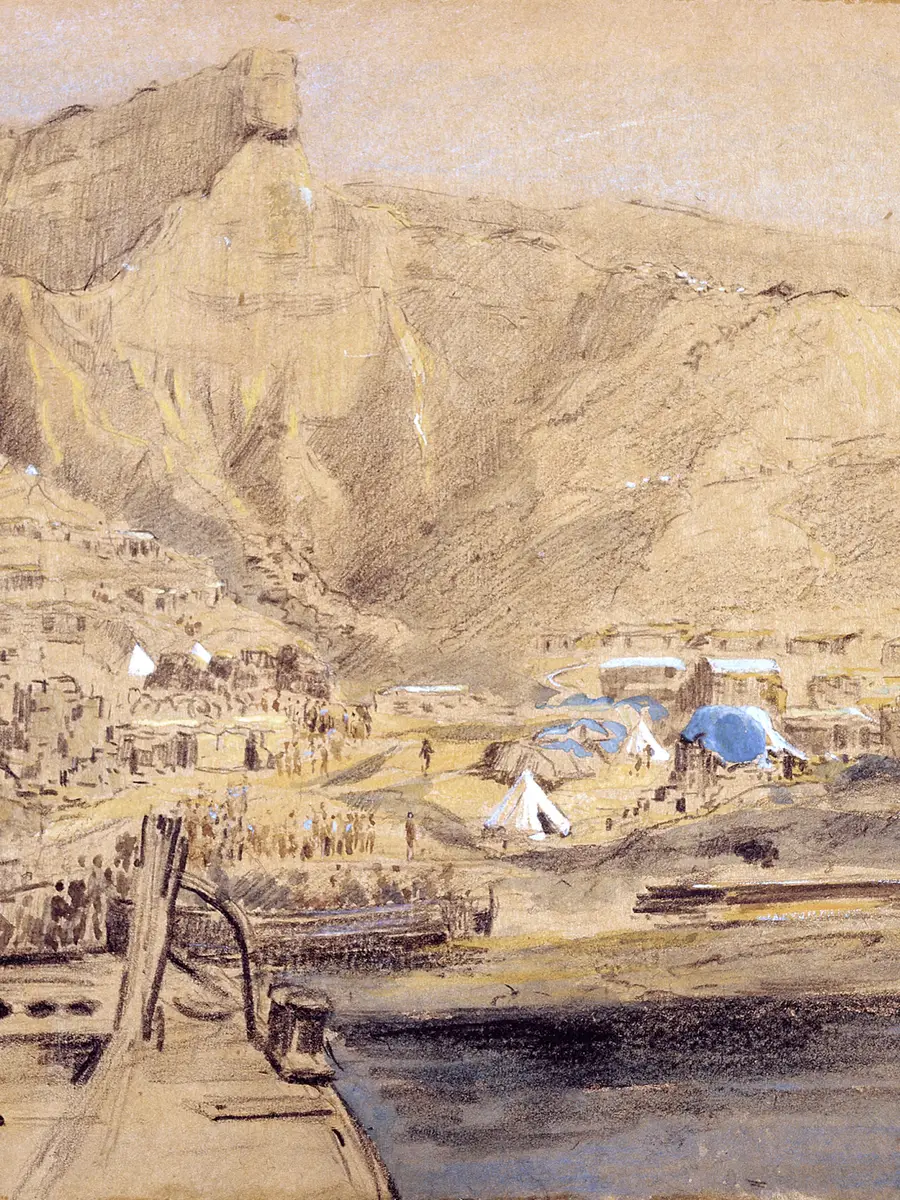

By contrast, George Lambert’s Jebel Saba, near Nalin depicts the no man’s land in the Judean Hills south of Jerusalem, with its rocky and inhospitable terrain.

George Lambert, Jebel Saba, near Nalin (1918), oil on wood panel. ART02698

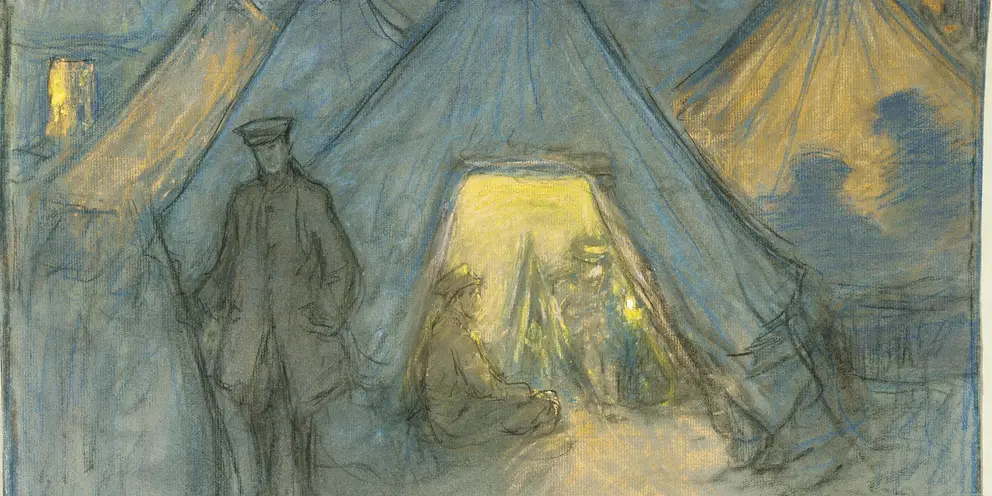

Iso Rae, Sentries at prisoners’ tent (1915), pastel, gouache on grey laid paper mounted on buff paper.

A number of artists outside the official scheme sought to record some of the less traditionally heroic aspects of the Australian experience. Working with the Voluntary Aid Detachment at Étaples Base in France, Iso Rae captured the camp’s day-to-day events and the tediousness of army life. Soldiers standing sentry in winter are stark against the warm glow emanating from the tents in Rae’s Sentries at prisoners’ tent.

Though most art works produced under the official scheme focused on war zones, towards the end of the war the home front became a focus. While women were often depicted in the roles of caring mothers, faithful wives or hopeful sweethearts, John Hepburn Cadell, who served with the 2nd Australian General Hospital in France, captured the role of working women in Nurse.

An unidentified young nurse is set against a fleur-de-lis background, suggesting France. Despite the artist’s decorative approach, the nurse is portrayed as a figure of calm dignity and endurance, reflecting a respect for her wartime service.

J.H. Cadell, Nurse (1918), watercolour on paper.

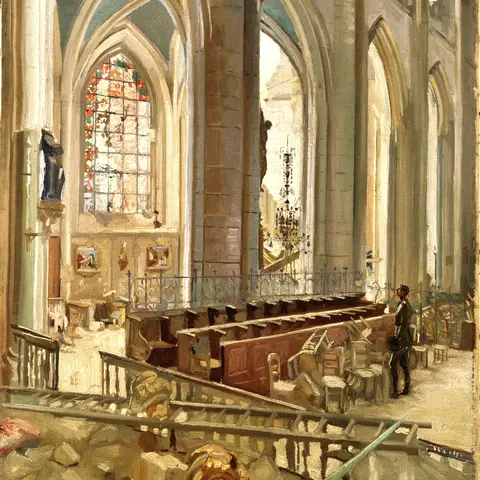

James F. Scott, Interior of Corbie Abbey, showing eff ect of shell-fi re (1918), oil on canvas.

In contrast to the initial enthusiasm for the war, works of art produced towards war’s end reflected the reality of conflict – its intense suffering but also its possibilities for hope.

In James F. Scott’s Interior of Corbie Abbey, showing effect of shell-fire, the abbey’s window glass and furnishings are still in place, even though the foreground is rubble. This work imparts a sense of war’s overwhelming destructive power, but at the same time also suggests low-key optimism, expressed in the buildings that were spared and a hint of the salvage eff orts at the end of the war.

Dora Meeson’s Departure of the last Australian hospital ship from Southampton, England, is most likely HMAHS Karoola embarking from London on 6 May 1919 with over 400 patients on board. Th e work is a similarly bittersweet reminder of the end of the war; the ship carries people we may call “war heroes”, but equally the war wounded, whose futures in Australia remain unknown, and for many in doubt.

Dora Meeson, Departure of the last Australian hospital ship from Southampton, England (1919), oil on canvas.