Stolen masterpieces. A hidden Nazi treasure trove. An Australian officer on a mission.

Hundreds of metres below the Austrian Alps, in the cool steady air of the Altaussee salt mine, an astonishing secret lay carefully concealed. More than 6,000 paintings plus sculptures, books, gold, weapons, even furniture – had been hidden by the Nazis.

In May 1945, a team known as the Monuments Men stepped inside to discover priceless works by Michelangelo, Vermeer and Rembrandt.

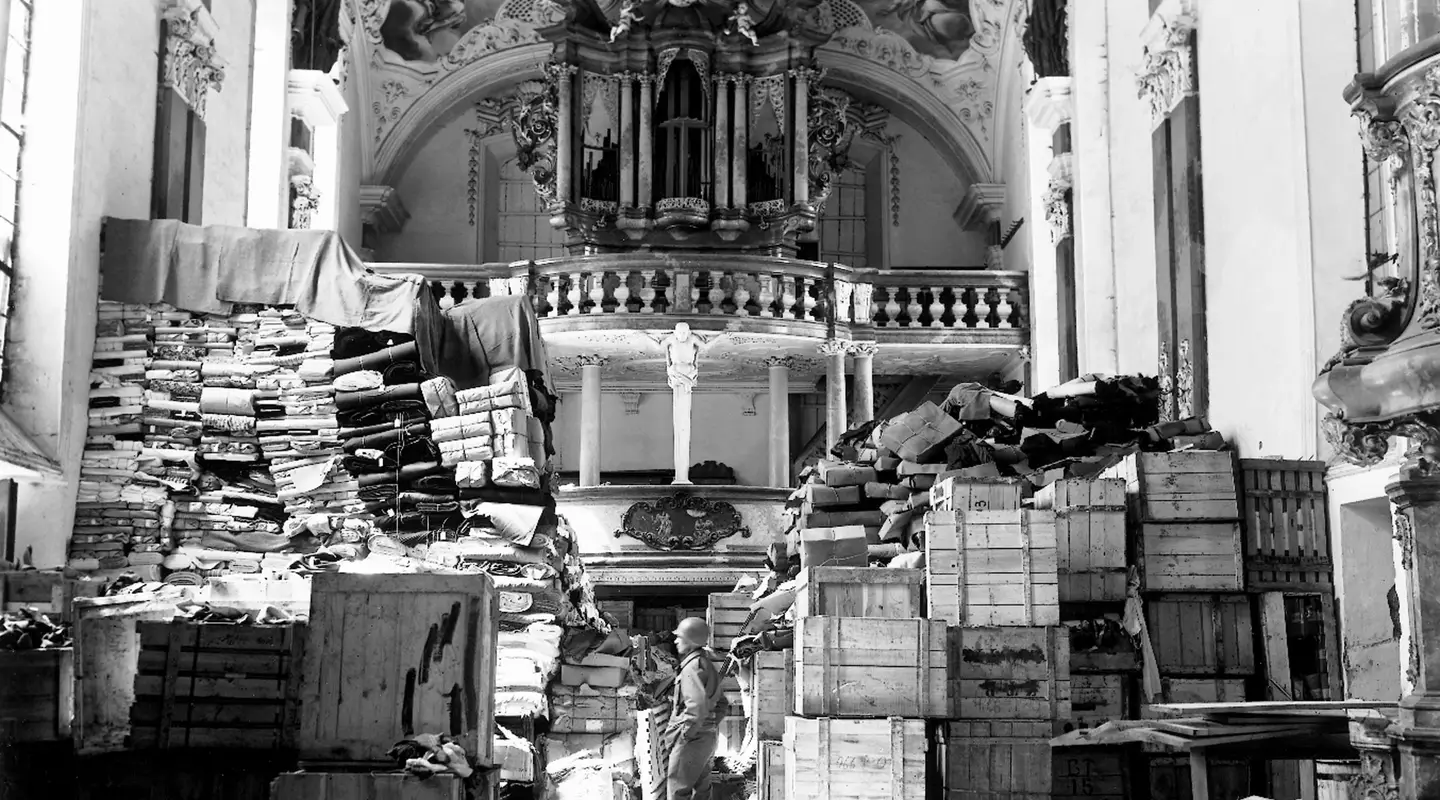

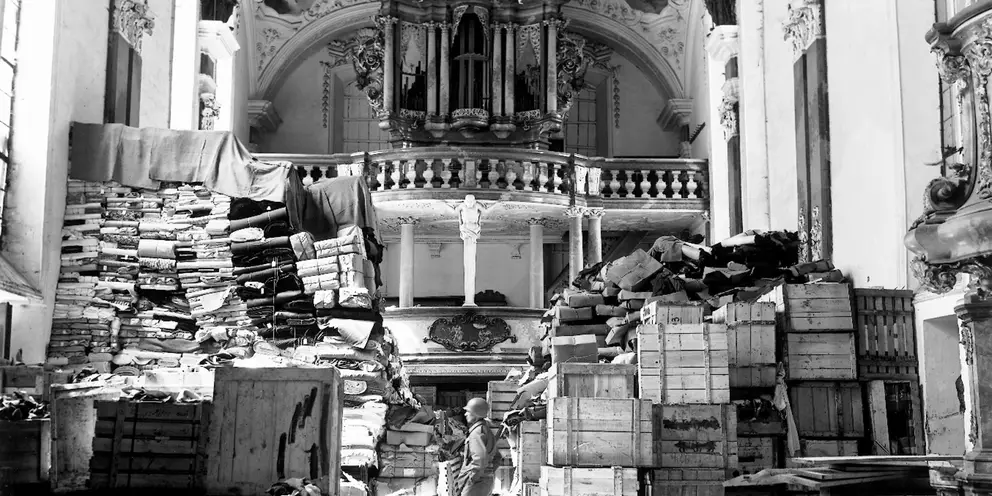

An American soldier inspects German loot, found at the Schlosskirche in the south German town Ellingen, 24 April 1945. Courtesy: The U.S National Archives and Records Administration, RG 111-SC-204899

Who were the Monuments Men?

The Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives (MFAA) section, better known as the Monuments Men, was formed in late 1943 to protect cultural artefacts and monuments from war damage and theft by the Nazi regime. A group of 350 to 400 artists, museum directors, curators, art historians and architects from 14 countries, they worked tirelessly to save cultural artefacts and return stolen treasures to their rightful owners.

With limited resources and minimal supervision, the men and women of the MFAA had to be highly resourceful.

“We had no trucks, no jeeps. Nothing but our shoes. And no support of any kind of officialdom.”

Monuments Officer Charles Parkhurst

Throughout 1944, they provided Allied troops with information on culturally significant sites, including statues, churches and monuments, to help minimise the damage caused by war. When damage did occur, they assessed and recorded details to help guide future restoration – all while trying to gather intelligence on Nazi looting and to find hidden caches of stolen art.

The MFAA had to safeguard monuments from enemy forces, and also to protect those treasures from the Allies. Soldiers, sometimes unaware of an object’s cultural significance, would sometimes take items from bombed buildings as souvenirs. “Off-limits” posters were designed by the MFAA to discourage trespassing and looting. As the war continued, however, looting became more widespread, a by-product of the devastation and desperation of the Second World War.

Australia’s Trojan Hero

Among these guardians of art was Aeneas John Lindsay McDonnell, the Australian representative to the MFAA. Named after his father (and the mythical hero of Troy and Rome who was the son of the goddess Aphrodite and the human Anchises), Aeneas McDonnell was well-suited for this unique and somewhat unconventional role. Fluent in French, and widely respected for his knowledge of European art, he was a passionate art collector.

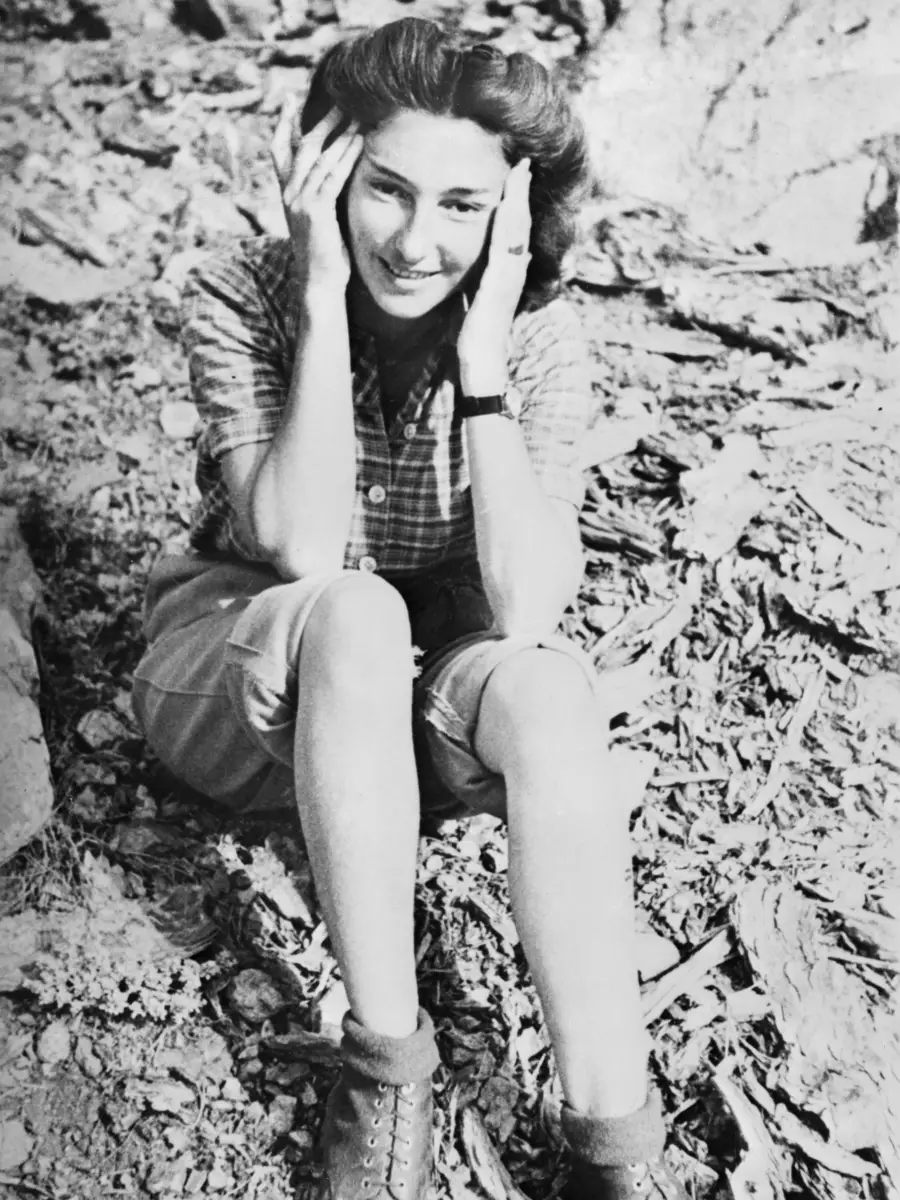

Lieutenant Colonel McDonnell while he was Chief Commissioner for the Australian Comforts Fund c. 1943. Photographer: Laurence Le Guay

School Prefects of Cranbrook School Sydney, 1922. Aeneas McDonnell is standing back row, second from the right. Courtesy of Cranbrook School Sydney

Born in Toowoomba and educated in Sydney, McDonnell had developed a lifelong passion for art. Though he had a particular fascination for French culture, his interests spanned several countries and historical periods. His enthusiasm led him to build a diverse collection of fine books, objects and artworks from around the world. In 1928, he became a partner at Macquarie Galleries in Sydney.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, McDonnell served overseas as the Chief Commissioner of the Australian Comforts Fund, working in Africa and the Middle East to support Australian troops. By May 1944, he had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force, and was transferred to the MFAA, where he was tasked with creating the MFAA Handbook for France.

Adolf Hitler and Hermann Goring in Goering's Berlin apartment, c. January 1938. Image courtesy of Federal Archives, Germany Bild 183-H00455

Nazi plunder

The Nazi Party undertook looting on an unprecedented, systematic scale. Initially this took place under the guise of Kunstschutz – the German policy of preserving cultural heritage and art through times of war, with the aim of protecting art and returning it after hostilities.

By 1940, however, the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce had been formed to gather cultural material belonging to Jews or opponents of the Nazi Party. Hitler later designated the taskforce as the only official art procurement organisation in occupied countries. It became instrumental in looting from private collections, state museums and the homes of those deported to concentration camps, plundering more than 600,000 artworks and other cultural items.

From as early as 1933, Jewish assets were being seized by the Third Reich. Prominent Jewish families with significant art collections were pressured into selling their collections for much less than their true value; the Rothschilds, a wealthy Jewish family, had more than 5,000 items confiscated from their collection.

This systematic stripping of assets not only provided the Nazi Party with a lucrative source of funds to continue waging war; it was also a fundamental part of the Holocaust. Seizing Jewish cultural property not only eliminated physical evidence of Jewish existence, but also served to hide their identity, heritage and history.

Führermuseum

Hitler’s grand plan for the Führermuseum fueled the plundering. The intended art museum was to be located in Linz, Austria (near his birthplace) and would house all the masters of European art.

Adolf Hitler had a well-documented love of art, having made his living as an artist and unsuccessfully attempting to become a student of the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. His feverish hatred of modern art, particularly Cubism, Futurism and Dadaism, was publicly enforced after he gained power as Chancellor of Germany in 1933.

Declaring that all “degenerate art” was to be sold or destroyed, he took actions to cleanse German culture of so-called degeneracy: there were public book burnings, artists and musicians were dismissed from teaching positions, and museum curators were replaced by members of the Nazi Party.

Photograph of the "salle des martyrs" (Martyrs Room) at the Museum of the Jeu de Paume in Paris (circa 1940). The room is filled with paintings stolen by the Nazis. Image courtesy of Archives French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Under the suggestion of Jacques Jaujard, Director of the French National Museums, curator Rose Valland continued working at the Jeu de Paume Museum during the German Occupation of Paris. The Nazis had commandeered the museum as a depot for the Rosenberg Taskforce to store and transport art, forbidding any French officials to remain, with the exception of the quiet and unassuming Valland.

For four years, Valland carefully disguised her understanding of German, speaking little and making herself unremarkable, while she memorised conversations and gathered intelligence about the artworks being catalogued, crated and transported for Hitler’s planned Fühermuseum. She would often take documents home at night to copy their information.

In The Monuments Men, author Robert Edsel speculates that McDonnell investigated Valland to determine whether she possessed useful information. McDonnell suspected she did not, as Valland hid her secrets well. Only after months of building trust with American Monuments Officer James Rorimer, did Valland reveal what she knew. Her meticulous documentation had recorded the whereabouts of more than 20,000 artworks.

Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany. Image courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

Hidden Treasures Found

As Allied armies moved into Germany and Austria in 1945, the Monuments Men uncovered vast repositories of stolen art. Castles, caves and abandoned mines offered the perfect spaces for concealment, with low humidity and safety from Allied bombings.

The first mine investigated by the Monuments Men in April 1945 was near Siegen in Germany. It contained works by Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Rubens, and an original score of Beethoven's Sixth Symphony.

The following month, McDonnell accompanied MFAA Officers on a ten-day inspection of stolen artworks. He witnessed the massive collections stored at Altaussee salt mine in Austria.

Some tunnels reached as far as 800 metres underground, where they found “6,577 canvases, 230 drawings and watercolors, 964 prints and 137 other valuable objects, including the Rothschild family jewels.” Among the treasures McDonnell saw were Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece and Michelangelo’s Bruges Madonna.

With intelligence provided by Rose Valland, the Monuments Men searched the fabulous neo-Gothic Neuschwanstein Castle, nestled in the Bavarian mountains.

Inside they discovered more than 20,000 objects, including paintings, tapestries and household items, along with documentation detailing the plundering operation of the Rosenberg Taskforce.

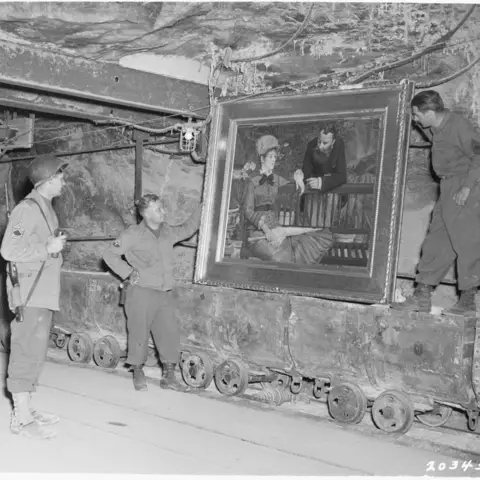

A painting by the french impressionist Edouard Manet, titled Wintergarden, discovered in the vault at Merkers in April 1945. Courtesy of The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, RG 111-SC-203453-5

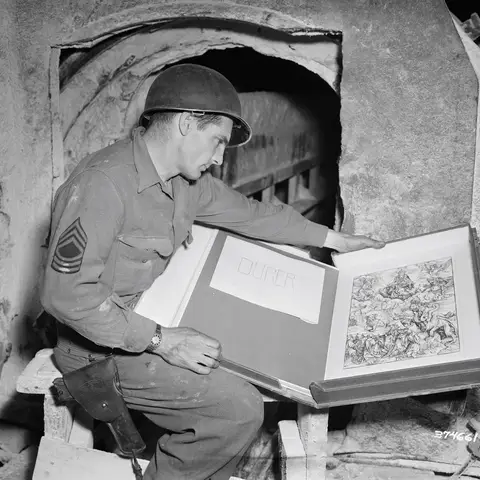

Sergeant Harold Maus of Scranton, PA is pictured with the Durer engraving, found among other art treasures at Merker. 13 May 1945. Courtesy of National Archives at College Park NAID: 5757194

Aeneas McDonnell continued to live and work in London after the war, but kept a close link with Australia. He served as the London advisor to the National Gallery of Victoria from 1947 to 1963, until his death in January 1964.

McDonnell was awarded the French Legion of Honour for his services to the French people. The award is now held alongside McDonnell’s other service medals in the Memorial’s National Collection.

“Major McDonnell was one Australian in a small Allied unit, who played a key role in saving hundreds of years of cultural history in Europe. The Memorial is proud to tell his story through his medals,” said Memorial Curator Cameron Ross.

An estimated 20 per cent of European art was looted during the Second World War, with more than 100,000 artworks still missing, including masterpieces by Edgar Degas, Anthony van Eck and Claude Monet. In 2013, a collection of 1,500 artworks was found in the Munich home of Cornelius Gurlitt, whose father had been an art dealer who worked with the Nazi party.

Thanks to the efforts of the Monuments Men, including Aeneas John Lindsay McDonnell, more than five million cultural treasures were tracked, located or returned. McDonnell’s contributions remain a testament to the role of Australia in preserving global cultural heritage, ensuring that the treasures – and the identities they represent – endured long after the war.