For more than 70 years Australia has been providing peacekeepers to the world and our region.

On 11 March 1989, 29-year-old Captain Craig Orme of the Royal Australian Armoured Corps was an observer with the United Nations (UN) mission in Iran, helping to supervise the ceasefire after the Iran– Iraq War. On that day, the UN observers received news that the Iranians were threatening to fire on the Iraqis over an alleged violation of the agreement. Orme and a Ghanaian officer went out to investigate, arriving at 1 pm. The Iraqis had built a bunker a mere 100 metres from the Iranian front line and the Iranians were demanding that it be removed by 2 pm. The Iranians brought a T-54 tank into a firing position on the embankment where Orme and his Ghanaian colleague were standing. Then, as Orme wrote in his diary, when a platoon of Iraqi soldiers with RPG-7 rocket launchers took up their firing positions, the Ghanaian “shot through to about 400m away with our vehicle leaving me with the tank and the Iranians.”

With the tank’s barrel resting between him and the senior Iranian officer, Orme tried to defuse the situation. As he wrote: “Eventually we were able to have it removed to calm things. I might add that I was walking around slowly as we were having our discussions in order to hide the fact that my legs were shaking!” Communicating with sector headquarters, Orme had the ceasefire extended until the next day, and remained until 4.30 pm, when the local Iranian commander was informed. Major General Slavko Jovic, head of the UN mission, reported to New York that “the prompt reaction of our UNMOs [UN observers] . . . put the situation under control.” Orme’s story is typical of a multitude of stories of Australian peacekeepers.

First peacekeepers

Australia’s experience of peacekeeping began in 1947, when the UN Consular Commission in Indonesia called for “military assistants” to help observe the ceasefire between the Dutch and the Indonesians. Four Australian military officers, led by Brigadier Lewis Dyke, arrived on 14 September and became the very first UN peacekeepers. From 1947 to 1951 at least 70 Australian observers served in Indonesia.

Since then, Australian peacekeeping has gone through a series of phases, the first lasting for the 25 years until 1972. During this time, with operational commitments in the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesian Confrontation and Vietnam, the Australian Army had little extra capacity to support international peacekeeping, and sent only small numbers of officers on observer missions. One such commitment was to Kashmir. In 1950, Major General Robert Nimmo was appointed to command the UN Military Observer Group in Kashmir, remaining in command until he died in January 1966. He was initially joined by eight Australian observers, and by the time Australia withdrew in 1985 a total of 180 Australians had served there.

The road between Skardu (Pakistani territory) and Kargil (Indian territory) winding along the Indus River, July 1965. The road was built by hand by Pakistani engineers. Photo: Barrie Malcolm Newman. P05689.044

Another commitment was to the UN Truce Supervision Organisation (UNTSO), monitoring the truce between Israel and its Arab neighbours. In 1956 Australia sent four officers and has maintained observers in UNTSO ever since, monitoring at close range the many wars involving Israel. Major Keith Howard was wounded during the 1967 Six-Day War, but continued serving in UNTSO until 1975, when he was acting Force Commander with the rank of colonel. It was still a risky mission. In 1988, Captain Peter McCarthy was killed when his vehicle struck a landmine in Lebanon.

Australia’s largest commitment during this time came from the Commonwealth and State police forces. In 1964 Australia sent police to join a UN force maintaining peace on the island of Cyprus. This commitment continued until 2017, with more than 1,600 police serving there. Two Australian police officers were killed in car accidents, and another was killed when his vehicle struck a landmine. Chief Inspector Jack Thurgar was awarded the Star of Courage for rescuing a badly wounded farmer from a minefield.

Second phase

The second phase of Australian peacekeeping began in 1972, after Australia withdrew from Vietnam. The newly elected prime minister, Gough Whitlam, was keen to increase Australia’s involvement in peacekeeping, and the subsequent Fraser government, elected in 1975, also supported international peacekeeping. But in the midst of the Cold War, the UN approved only a few new peacekeeping missions, so there were limited opportunities. One was to provide a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Caribou transport aircraft for the Kashmir observer mission from 1975 to 1979. As well, from 1976 to 1979, four RAAF Iroquois helicopters provided transport for UN observers watching the Israel–Egypt border along the Suez Canal after the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

When Israel agreed to withdraw from the Sinai Peninsula in 1978, the Soviet Union threatened to veto the deployment of a UN observer force, so the United States set up its own Multinational Force and Observers to monitor the Sinai. Australia provided eight helicopters to this force from 1982 to 1986, and after 1993 sent observers. From 1994 to 1997, the force was commanded by an Australian officer, Major General David Ferguson.

Another peacekeeping mission that operated outside the UN framework was the Commonwealth Monitoring Force in Rhodesia/Zimbabwe. From December 1979 to March 1980, troops from five Commonwealth countries, including 150 Australian soldiers, monitored assembly places used by Patriotic Front guerrillas, kept an eye on Rhodesian troops and tried to maintain law and order during the election.

A golden age of peacekeeping

By the mid-1980s, Australia had only 20 police on peacekeeping duties in Cyprus and 13 military observers in UNTSO. It was not until 1988, as the Cold War was drawing to a close, that Australia became more heavily involved in peacekeeping, beginning the third phase, a golden age of Australian peacekeeping. The Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, was taking a more cooperative approach, and the UN formed an observer mission to monitor the ceasefire between Iraq and Iran. Australia despatched four consecutive contingents, each of 15 officers; Captain Orme was in the first contingent.

With the end of the Cold War, it was possible to end the war in Southwest Africa (now Namibia). The UN deployed a large peacekeeping force to facilitate elections for a new government, and Australia sent an engineer contingent of 300 soldiers. The Australians arrived first, in March 1989, to be faced by guerrilla fighters returning from Angola. The engineers helped establish assembly points for the guerrillas, where they would be safe from attack by the South Africans, thereby saving the peace arrangements. Later in 1989, a second Australian contingent assisted with the conduct of the successful election, which resulted in the formation of a new government for Namibia. Peacekeeping had now moved well beyond observing.

More Australian deployments were to follow. In 1988 the Soviet Union withdrew its forces from Afghanistan. The UN established a mine-clearance training mission in Pakistan for Afghan refugees, so that they could return to Afghanistan and clear the millions of mines left over from the conflict. In July 1989 Australia sent a small mine-clearance training team, but eventually Australia became the most important nation in the program, and its trainers remained until 1994. A total of 92 Australians served with the team.

The end of the Cold War brought further changes to the nature of peacekeeping. In August 1990, Iraq under Saddam Hussein invaded and seized Kuwait, just at the time when Gorbachev, US President George H.W. Bush and Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke were talking of a “new world order” that would “bring an era of peace”. In an effort to make Iraq withdraw from Kuwait, the UN authorised the formation of a multinational naval force to prevent Iraq from exporting oil and importing other goods. Australia provided three warships to the US-led force. When Iraq did not comply, the UN authorised the multinational force to take military action under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. This Gulf War, which began in January 1991, and ended a month later, could be described as peace enforcement. Australia deployed three warships and other personnel during the war.

The end of the Gulf War was to generate more peacekeeping missions. In 1991 Australia sent a medical unit of 75 members on Operation Habitat to provide assistance to Kurdish refugees in northern Iraq. The operation was the first in which Australian servicewomen were deployed overseas on an equal basis with men.

Australian military observers serving as part of the United Nations Iran-Iraq Military Observer Group (UNIIMOG), beside the Shatt-Al-Arab waterway, Iran, 1989. Photo: Michael Coyne.

The UN Security Council demanded that Iraq allow UN inspectors to come into its country to locate and destroy its weapons of mass destruction, i.e. its chemical, biological and nuclear weapons, and rockets for delivering them. The inspectors of the UN Special Commission on Iraq (UNSCOM) came from a range of countries, and Australians (125 over eight years) played key roles. The Australian diplomat Richard Butler led UNSCOM from 1997 until its conclusion in 1999. The UN naval interception force in the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, periodically including Australian warships, continued to apply sanctions in order to force Iraq to accept the UNSCOM inspectors.

Foreign Minister Senator Gareth Evans declared that, as “a good international citizen”, Australia should support international peacekeeping. Hence, from 1991 to 1994 more than 230 Australian signallers took part in the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. The Australian force’s medical officer, Major Susan Felsche, was one of those killed in a small plane crash in June 1993.

Senator Evans played a major role in brokering a UN peace agreement in Cambodia, where a civil war had been raging for many years. Australian Lieutenant General John Sanderson commanded the UN force of 16,000 troops who deployed throughout the country between 1991 and 1993, helping to facilitate the election of a new government. Australia provided the Force Communications Unit; in total, some 1,140 Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel served in Cambodia.

Yet Australia could not meet every demand for peacekeepers. When Yugoslavia disintegrated into war from 1991, Prime Minister Paul Keating resisted UN requests for assistance. Just four Australian observers were redeployed from Israel to Bosnia. Colonel John Wilson headed the UN observer mission in 1992, and later, as a brigadier, was the chief military adviser to the UN special envoy. Then, after NATO became involved, some 260 Australians served with British and American NATO forces in the former Yugoslavia until 2004.

When Somalia collapsed into anarchy in 1992, the UN established a peacekeeping mission and Australia deployed a movement control unit.

The next year, Australia contributed an infantry battalion group of 1,000 personnel to an American-led task force to protect the delivery of humanitarian aid. Over a four-month period the Australians maintained an armed presence, escorted aid convoys, attempted to reduce the numbers of weapons in private hands, and began rebuilding institutions of civil society. During one patrol, Lance Corporal Shannon McAliney was accidentally shot dead. The commander of the Australian battalion, Lieutenant Colonel David Hurley, later became Chief of the Defence Force and Governor-General.

Members of the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF), Solomon Islands, c. June, 2000. This was the first time the group had been photographed by overseas media. Photo: Ben Bohane.

Australia led the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI).

The UN forces in Somalia were restricted in what they could achieve. Some Australians, including RAAF air traffic controllers, were still in Somalia when the battle of Mogadishu erupted in October 1993. As a result, US President Bill Clinton decided to withdraw the US forces, and gradually the other international forces left as well, leaving Somalia to its own predicament.

The problem of operating with a restricted mandate was repeated in Rwanda in 1994, when a small UN peacekeeping force was unable to prevent the massacre of about 800,000 Rwandans by Hutu extremists. Along with the rest of the world, Australia was slow to react, but eventually between August 1994 and August 1995 Australia sent two contingents of 300 ADF personnel consecutively to provide medical support for the UN Force and medical assistance to the Rwandans.

In April 1995 an Australian medical team with a small infantry protection group were present at the Kibeho refugee camp when government forces massacred about 4,000 refugees. Captain Carol Vaughan-Evans, who headed the medical team, Lieutenant Steven Tilbrook, the infantry commander, Warrant Officer Roderick Scott and Lance Corporal Andrew Miller were awarded the Medal for Gallantry – Australia’s first decorations for gallantry since the Vietnam War.

Finally, in this “golden age” of Australian peacekeeping, Australia deployed mine-clearance training teams to Cambodia and Mozambique. Members of the Australian Federal Police (AFP) assisted with elections in Mozambique, and between November 1994 and May 1995, 31 members of the AFP went to Haiti as part of a UN mission to help re-establish the Haitian police.

Closer to home

By the mid-1990s, after the disasters in the former Yugoslavia, Somalia and Rwanda, the international community was losing its enthusiasm for UN peacekeeping. Australia ended its large commitments to distant UN missions and concentrated its efforts closer to home.

The first effort took place on the island of Bougainville, where secessionists were fighting the Papua New Guinea Defence Force. In 1994, Australia led a regional peacekeeping force that included troops from New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu to provide security for a peace conference on Bougainville. This was the first time that Australia had to plan, mount and lead an international peacekeeping mission.

Although the 1994 conference failed, in 1997 New Zealand was able to facilitate a successful peace conference. A truce was signed, and New Zealand led a Truce Monitoring Group to Bougainville with members from Australia, Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu. Four months later, after a peace agreement had been signed, the Truce Monitoring Group became the Peace Monitoring Group, with Australia as the leader.

With the military providing much of the logistic support and the command element, many of the observers were civilians. As everyone in the mission was unarmed, they relied on the local Bougainvilleans for their security. This was not just an observer mission; members promoted the idea of peace, facilitated reconciliation and supervised the surrender of weapons, while diplomats assisted the protagonists to come to an agreement. By the time the mission withdrew in 2003, more than 2,300 Australians had served in it.

By this stage, Australia had become involved in its largest and most important peacekeeping mission in the Indonesian territory of East Timor. In 1999 the UN sent a mission to East Timor to supervise a plebiscite over the future of the territory, and Australia contributed civilian police. Local militias began a vicious terror campaign against those who supported independence. Nonetheless, in August 1999, the East Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence. The militias stepped up their terrorist attacks and RAAF aircraft then helped evacuate the UN personnel to Australia.

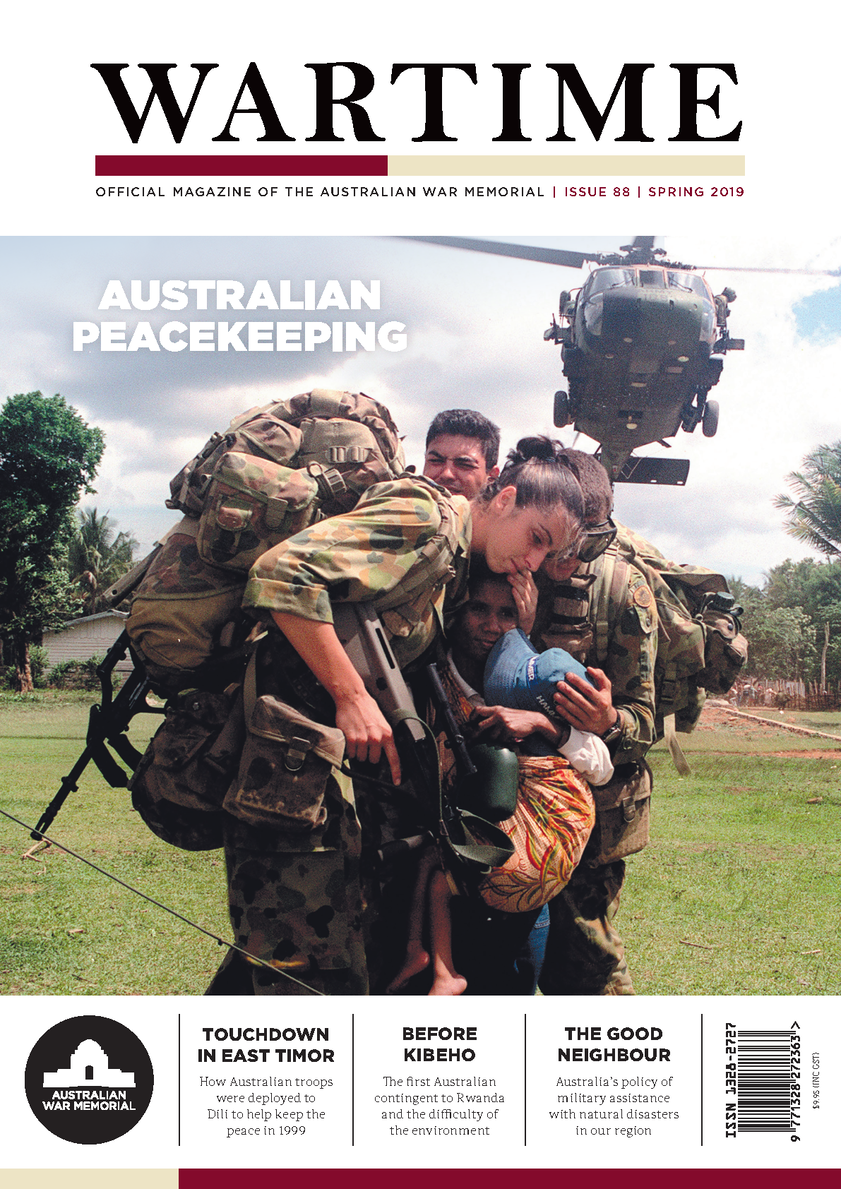

With Indonesia unable to stop the killing, the UN and the United States pressured Indonesia to allow an Australian-led peacekeeping force, the International Force East Timor (Interfet), to deploy to East Timor to restore order. On the morning of 20 September 1999, RAAF aircraft began landing Australian, New Zealand and British Gurkha troops at the Dili airfield. These were followed by troops from a naval task group, which included eight Australian warships and one each from New Zealand and the United Kingdom. Australia provided 5,500 of Interfet’s 11,500 personnel, including the Commander, Major General Peter Cosgrove, who would later become Chief of the Defence Force, then Governor-General.

LEUT Miquela Riley, RAN near UNTSO HQ in Jerusalem

In February 2000, after security improved, the UN Transitional Administration in East Timor took over from Interfet and Australia’s contribution was reduced to about 1,550 personnel. Australian troops remained in the new state of East Timor, now called Timor-Leste, until 2005. There were continuing problems, however, and in 2006 more than 800 Australian troops returned to Timor-Leste to assist the government to maintain security.

Australia was once again involved in a regional mission in 2003, when the Solomon Islands government was unable to maintain law and order, and asked Australia to assist. Australia led the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (Ramsi), which also included police and military from New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Fiji and Tonga. The mission marked a new development in Australian peacekeeping, in that it was led for the first time by an Australian diplomat, Nick Warner.

Further, the law enforcement component was headed by an Australian police officer, Ben McDevitt, who led a composite police force from several countries. Security was provided by an Australian infantry battalion, assisted by troops from other countries. Gradually the military support was cut back. Unfortunately, Protective Service Officer Adam Dunning was shot and killed in 2004, and Private Jamie Clark was killed in an accidental fall in 2005. In 2006 there was more violence and, at the request of the Solomon Islands government, Australia quickly redeployed troops to quell the violence. This was followed by a gradual withdrawal. By the time the last Australian troops departed in 2013, a total of 7,270 Australian personnel had served in Ramsi.

New focus

Even before the Ramsi mission, the ADF had moved its focus away from peacekeeping. After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington in September 2001, Australia deployed forces to military operations in Afghanistan and, from 2003, in Iraq. These demanding commitments left little capacity to send forces to new distant peacekeeping missions.

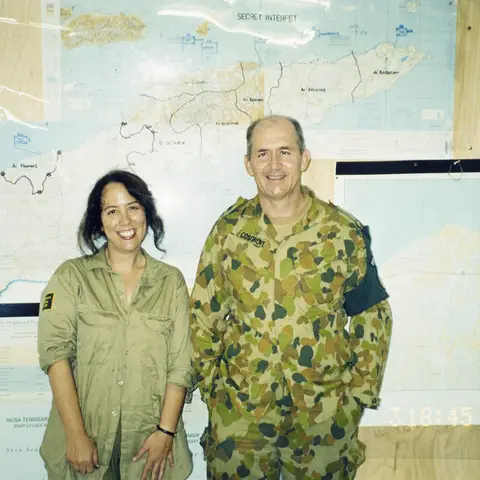

Dili, East Timor. 23 December 1999. Informal portrait of Wendy Sharpe (left), Australian Official Artist, with Major General Peter Cosgrove, Commander of the International Force for East Timor (Interfet), in the Interfet Headquarters.

As the regional missions wound down after 2006, Australia’s peacekeeping entered a new phase of limited commitment. Nevertheless, Australia still sent small contingents to Sierra Leone, Eritrea and Sudan. Australia continued to deploy observers to Untso, monitoring the uneasy peace between Israel and Syria. Australia’s continuing role was recognised when Major General Tim Ford was appointed to command Untso from 1998 to 2002. He subsequently became Chief Military Adviser at UN Headquarters in New York.

Having demonstrated its military expertise, Australia is still called upon to support international peacekeeping. For example, in 2006 Major General Ian Gordon was appointed to command Untso; in 2017 Major General Simon Stuart took command of the Multinational Force and Observers; and 2018 Major General Cheryl Pearce was appointed commander of the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus.

In the 72 years since Australia deployed its first peacekeepers overseas, fortunately only 16 have died on deployment: four civilian police officers and the remainder from the Army. Nonetheless, peacekeeping could be difficult, arduous and also extremely dangerous, especially when the carrying of weapons was not permitted. Many peacekeepers have suffered from post-traumatic stress.

From the late 1980s to 2006, peacekeeping was a major activity of the ADF. In this time, peacekeeping grew in complexity, moving from observing to supporting elections, clearing mines and inspecting weapons. Peacekeeping transformed into peace enforcement, from providing security against marauding militias, to actual combat, as in the Gulf War. The ADF gained valuable experience in preparing for later overseas operations and in working in challenging environments. Similarly, peacekeeping became a major task for the AFP and ultimately soldiers, police and civilians learned to work together. Peacekeeping has a distinguished place in Australia’s military history.

An Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM) guerrilla on patrol on the Weather Coast, Guadalcanal, 2000. Photo: Ben Bohane. P04580.059