Morale and combat motivation of Commonwealth soldiers in the two World Wars.

The twentieth century industrialised battlefield was a dominion of fear. From Gallipoli, coming under bombardment for the first time, a New Zealand artillery officer wrote simply, “I was never more frightened in my life.” A generation and a war later, a British infantryman fighting in Italy wrote to his wife, “We all know fear.”

To be frightened was not necessarily the same as showing cowardice. All but a handful of men, perhaps 2 per cent, felt fear in battle. Soldiers who showed fear could be treated with compassion. During the brutal fighting in Germany in early 1945, a British infantryman reacted to enemy mortar fire by soiling himself. His sympathetic comrades cleaned him up.

For a soldier to react like this was fairly unusual. Most toughed it out. Tasmanian Private George Vaughan, of the 12th Battalion 1st AIF, landed on Gallipoli on the first Anzac Day. He wrote home that the censor prevented him from discussing casualties, but “The fighting for the first few days was of the fiercest, and I had no doubt that one who could ‘stick it’ for three days would die as he fought.” Vaughan was wounded on 25 April. Reading between the lines of his understated letter, Vaughan had been under severe stress, and recognised that he had been fortunate to receive a minor wound early on and thus avoid the attritional killing of the hours and days that followed.

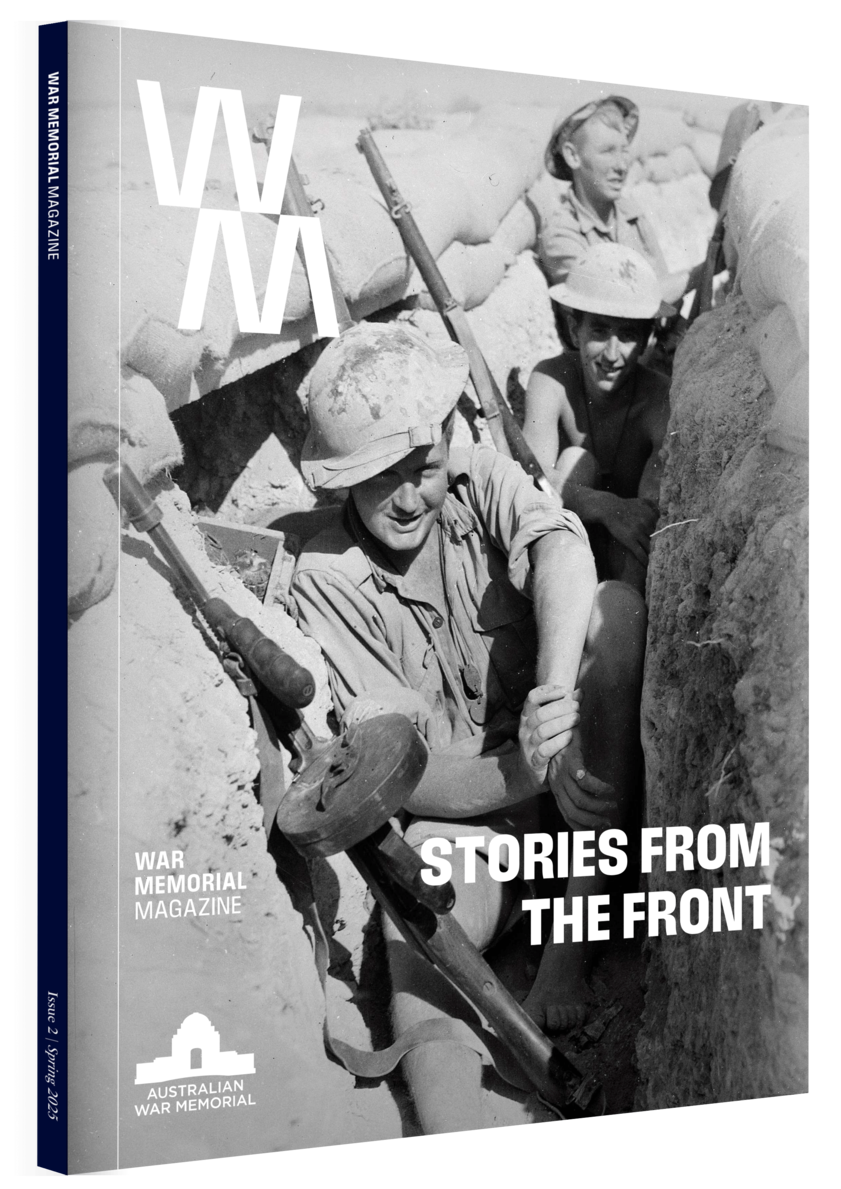

In battle, officers and NCOs led by example, converting sound morale into combat motivation. AWM 006642

And yet men, somehow, coped. Private William Salter of the 1st AIF wrote in May 1917 that

"Ordinarily men could never endure the awful nerve-racking circumstances. The terrific din, the shocking sights, the grim work … the dreadful horror staggers the senses … If in everyday life one came across a body lying by the roadside in a similar condition to that in which he sees scores on the battlefield, the sight would unnerve him for days after: but at the front one works surrounded by death in the most horrifying forms without scarcely a sense of revulsion."

When faced with extreme danger, the natural reaction of human beings is to run away. One of the principal purposes of the initial training – or conditioning – that all recruits undergo is to override that impulse, so soldiers will choose ‘fight’ rather than ‘flight’. Other factors, such as the desire not to let their comrades or unit down, or to appear cowardly or ‘unmanly’, also play a role in keeping men in the firing line. Above all, otherwise very ordinary people proved amazingly resilient in the face of appalling stresses.

How men managed fear, and overcame it to fight effectively, is central to understanding battle. In a short article, some key factors unfortunately are passed over quickly or ignored. These include the roles of ideology, religion, training, comradeship and unit pride. But drawing on rich sources of evidence from both world wars about soldiers from Britain, Australia, and New Zealand – men from broadly similar societies with comparable (although not identical) experiences and attitudes – this article aims to help us understand a little more about this crucial aspect of combat in 1914–18 and 1939–45.

Noise

The sheer noise of the battlefield was disorienting. “Under heavy fire,” Private Eric Ratcliff (12th Battalion AIF) wrote from Gallipoli, “this crack, crack [of rifle fire] is deafening, and when our rifles begin to speak you can imagine the din.” To noise must be added fatigue, which could become extreme. The 1st Worcesters, holding the line in north-west Europe in November 1944, were relieved by another battalion of the 43rd (Wessex) Division, but “We were almost too worn out to care.” They got aboard the vehicle that took them to the rear area “like so many sleepwalkers”. The ‘minor horrors of war’ such as dirt, lice, rats, mosquitoes and flies added to the stress.

Wounded at the Gallipoli landing,

Private George Vaughan knew he

had been lucky to survive. He was

commissioned and awarded a

Military Cross and Bar on the

Western Front.

So did, for green soldiers, anticipation of battle. Combat veterans knew what was coming up. Virgin soldiers, waiting to take part in their first action, constructed their picture of battle from reading, watching war films, old soldiers’ stories (some more accurate than others) and their imagination, which was often working overtime.

Then came the real thing. The first sight of dead and wounded was jarring. Bertie Marina, an Australian artilleryman at Anzac, wrote about his first action: “You can’t realise what war is until you have been in the thick of it …The man who wants to tell me that he didn’t feel nervy the first time under fire is a darned liar … [but] It is wonderful how soon one becomes used to it.” Being fresh to battle had its pluses.

A “sense of adventure, with its supercharged impulses of curiosity and excitement”, wrote David Cole, a British officer in 2/Inniskilling Fusiliers in Italy in the Second World War, “was one of the few advantages that the infantryman new to battle enjoyed over the veteran … It would, alas, gradually fade away … and [we would] have to draw more and more deeply on our innermost resources of discipline, comradeship, endurance and fortitude.” Lance Corporal Thomas Durant, 13th Australian Light Horse on Gallipoli, put it more simply: in September 1915 he wrote that “We are constantly playing with death; there is always the chance of being hit with a shrapnel shell or a rifle bullet … [but it is] surprising what one can put up with.”

Marina, Cole, and Durant testified to one essential truth: green troops became veterans remarkably quickly. If they did not swiftly become battlewise, their chances of being killed or wounded increased dramatically. Part of this learning process was working out how to cope with the extreme stress of battle.

Shock

But human beings can only take so much, and for some men intense, continual combat brought mental wounds, called ‘shellshock’ in the Great War and being ‘bomb happy’ in 1939–45. A young Coldstream Guards officer, Jocelyn Pereira, who fought in Normandy in 1944, wrote an extremely perceptive analysis of the stress of combat:

"In the end something gives ... There is something horrifyingly grotesque about seeing a sane individual suddenly turn into a gibbering idiot shaken by an uncontrollable hysteria ... It was the long days of exposure in slit trenches open to the sun and the rain and the intense cold at nights that wore people down, and when you are physically exhausted it is only a small step on to nervous exhaustion."

In the words of Lord Moran, a British Regimental Medical Officer in the Great War and author of a valuable study of battlestress, "there was no such thing as getting used to battle. Men, like clothes, simply wore out." A famous study by two Americans, Swank and Marchand, plotted the effectiveness of men in battle.

As they gained experience, soldiers became more effective; but if they went on too long, were exposed to too high a level of stress, their effectiveness declined sharply. This could simply mean that soldiers became increasingly reluctant to fight. After many months of fighting in Burma, Patrick Davis, a British officer of 4/8 Gurkhas, realised that “whatever it is that keeps us going willingly and ardently into battle had for me run out. Will-power and pride bore me along after a fashion … But from now on I never volunteered.”

Soldiers, who were mostly young men, liked to be believe that they were invulnerable. But time after time they were presented with the evidence of their own eyes that one day their luck was likely to run out. Lieutenant Irwin Burges (10th Australian Light Horse) wrote from a hospital in London of an attack on Gallipoli on 7 August 1915:

Our poor fellows fell in rows, not one man got more than a few yards from our own trenches. They were mown down like corn … we lost 88 men killed outright and 84 badly wounded in five minutes. We survivors crawled back slowly. To move meant death and some took hours to crawl ten yards.

Gallipoli was a particularly tough battlefield. Nowhere was safe from enemy fire. As a British soldier put it, “There is no ‘off time’ on the Peninsula, and the firing goes on forever.”

The same was true of the Anzio beachhead in Italy in 1944. In other campaigns, such as the Western Front in 1914–18, or Normandy in 1944, there was at least the possibility of periods behind the lines in relative safety.

A wounded soldier calms a shellshocked comrade. New Britain, March 1945.

Other men suffering from severe battle fatigue took matters a stage further by going absent without leave or deserting, or deliberately wounding themselves to try to escape from the danger. Collectively, it could mean ‘combat refusal’, or out-and-out mutiny. In September 1918, some Australian units on the Western Front decided enough was enough. No one can doubt the courage or fighting ability of the Australian Corps in the Hundred Days that defeated the German Army. But understrength and running short of reinforcements (a consequence of Australia’s rejection of conscription in two referenda), some Diggers baulked at being thrown into battle yet again.

The 59th Battalion had just come out of the line on 14 September after a week of stiff fighting, when it was directed to return to the front. Soldiers angrily refused the order, and had to be persuaded by their officers. A similar but even more serious incident took place a little later in the 1st Battalion, which eventually returned to the line minus 119 men, who had refused to go. Similarly in the Western Desert in 1942. the elite British Guards Brigade’s morale went from ‘outstanding’ in March 1942 to having the ‘lowest’ morale in Eighth Army in August 1942. One Guards ranker wrote it was “always the same men who were sent into action”, then “worn out by the desert and the strain of battle, they crack.”

Morale

The numbers of cases of sickness and indiscipline in a unit was generally a reliable guide to the state of morale and cohesion. For both ANZAC and British VIII Corps on Gallipoli, despite heavy losses and appalling conditions which led to endemic dysentery and other foul diseases, sick rates were manageable during the first part of the campaign. Most soldiers believed that the allies would achieve victory at the Dardanelles. A typical sentiment was expressed by an Australian gunner in June 1915: “hope it won’t be long before the job is brought to a successful finish.” Many ill men doggedly stayed with their units rather than reporting sick. But then came the failure of the August Offensive, which brought about a collapse in the belief in victory, and with it, severe damage to morale. Sick rates rocketed. In reality men were no more or less ill than earlier, but now they largely stopped trying to tough it out. Similarly, cases of indiscipline climbed.

As these examples indicate, no unit or individual’s morale was static. As Patrick Davis wrote, “Courage waxes and wanes in the same man, relative to hunger, health, fatigue, nervous exhaustion, and other externalities.” Yet, with some notable exceptions, the morale of the armies of the British Empire in the two world wars proved to be, if not universally excellent, at least good enough. What kept morale at this level?

“There was no such thing as getting used to battle. Men, like clothes, simply wore out.” A bunker at Menin Road

in the First World War.

The role of NCOs and officers was crucial. Their ethos demanded that they needed to ensure that their men were well cared for: this ‘paternalism’ was a major strength of armies that came from the British tradition. To take one example, one of the key roles of the leader was to keep their soldiers busy with tasks, and in rear areas, organised activities such as sports. One of the ‘stressors’ that caused stress included tedium. According to a soldier of the 2nd AIF, “Monotony is the ‘enemy in chief’!” Even at the siege of Tobruk in 1941, when the Australian–British garrison was frequently in action, one digger of 2/28th Battalion said it was ‘ninety-five per cent boredom and five per cent action’.

In rear areas boredom was a particular challenge. To be bored and lacking information was particularly soul-destroying. Men craved diversion. Books and newspapers became treasured possessions, passed from hand to hand. In Tunisia in 1943, British soldiers ‘were reduced the passing the long hours by organising beetle-races along the walls of our trenches … We would set them off together, encouraging them along with bits of sticks and getting excited as an ‘Ascot’ crowd.” Boredom gave time for brooding, which undermined morale, and officers and NCOs did their best to keep their men from getting bored.

Violent death, which would have unnerved men at home, became all too common a sight on the

battlefield.

In battle, officers and NCOs led by example, converting sound morale (in the sense that soldiers did not run away) into combat motivation: ensuring that soldiers were willing to advance and attack. Such leadership from the front meant that disproportionate numbers of junior officers were killed and wounded. It was not only infantry officers who played this role. In Italy in 1945 Captain S.A. Jackson of the Royal Army Service Corps – a logistician – won a well-deserved Military Cross in for his role getting a Commando troop carried in ‘Fantail’ Armoured Personnel Carriers across the River Reno under heavy enemy fire, showing ‘complete disregard of danger’. Jackson’s example led other APC drivers to follow his lead and get the Commandos into action.

Captain Bert Jacka VC MC and Bar was an extraordinary individual who made a crucial difference in

dire situations.

In many actions, when soldiers’ resolve was wavering, the action of an exceptional individual, a ‘Big Man’, made the crucial difference. These were not necessarily formal leaders. Some were rewarded with gallantry awards. Bert Jacka, who won Australia’s first Victoria Cross of the Great War at Anzac, was one of these. He should have received a Bar to his VC for his outstanding act of leadership at Pozieres in 1916. Company Sergeant Major Stan Hollis (of the 6th Green Howards), the only man to be awarded a VC for his actions on D-Day, was another. So was Tom ‘Diver’ Derrick (2/48th Battalion), who won a Distinguished Conduct medal in the Western Desert and a VC in the Pacific.

But so many more never received recognition they deserved. One was Private Ken Pollitt (7th Royal Welsh Fusiliers). In Holland in late 1944, his platoon was faced with a tricky tactical situation. They needed to cross a road swept by enemy fire, but they hesitated. Pollitt took charge and organised the sprint through the danger zone. This was a spur-of-the-moment decision, and fifty years later he was not entirely sure why he had made it. Probably the answer is that Pollitt was, by this stage, a battlewise combat veteran: he recognised the need for leadership, and instinctively provided it. This was an unspectacular act of minor leadership but it, and countless similar deeds performed by innumerable soldiers, enabled civilian soldiers to overcome the dominion of fear, to fight effectively, and ultimately to achieve victory.