The official history of Australia’s role in the East Timor crisis: the lead up, the events and the lessons learned.

Since the 1921 publication of Volume I of the Official History of Australia in the War of 1914– 1918 under Charles Bean’s editorship, more than 40 Australian historians, ably assisted by an untold number of research assistants, have produced around 38,000 pages providing a comprehensive and authoritative account of Australia at war and on warlike operations. Craig Stockings’ work, the 56th title in the official histories project, continues that tradition.

Born of Fire and Ash turns the Official Historian’s gaze to East Timor, specifically to Australian operations in response to the East Timor crisis of 1999– 2000. It will be followed by subsequent titles detailing Australian operations in Timor in 2000-2005 (by Andrew Richardson), and Australian operations from 2006 (by Will Westerman).

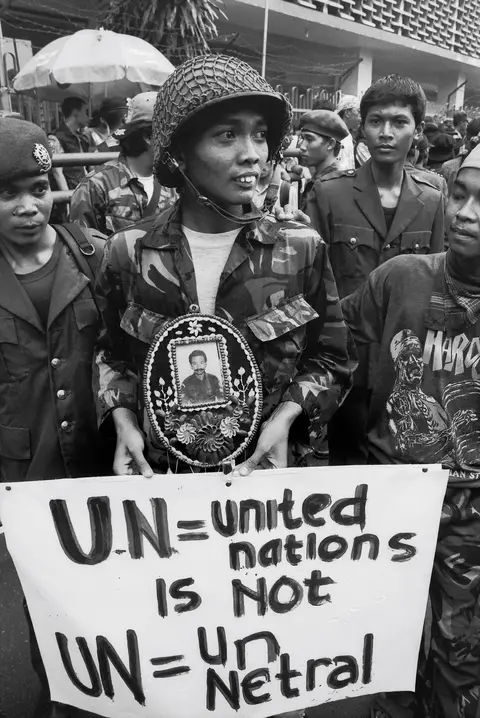

Protesters rally in Jakarta against the Australian-led International Force East Timor, 1999. Photographer: David Dare Parker

As would be expected, Stockings’ work provides an authoritative account of Australian military operations during INTERFET. It focuses on the actions performed by Australia and its international partners but, where necessary, also on the lessons learned and shortcomings of those events.

His account of the action between a six-man Special Forces patrol and an estimated 20 to 60 militiamen near Aidabasalala on 16 October 1999, for example, provides an in-depth account drawn in part from official sources and interviews with those involved.

Notable is the discussion about the success and utility (or futility) of the events, and how they exposed tensions within INTERFET’s command structure. Although it was considered a success by Special Forces, Stockings points out that the Special Forces action thwarted 2RAR’s larger sweeping operation in the Aidabasalala area, planned for the coming days.

As then Lieutenant Colonel Mick Slater, commander of 2RAR, put it, “They raced down to try and get themselves some scalps and they f----d it up again.” The Aidabasalala story is not new, but Stockings’ discussion of it is the most comprehensive to date and is emblematic of his tendency not only to describe events, but to examine the issues involved and lessons learned.

The aspect of Born of Fire and Ash that has generated the most discussion, and has proved the most controversial, has been Stockings’ account of the events leading up to the Australian deployments of 1999.

It is not until some 420 pages into the 900-page book that INTERFET boots hit the ground. The pages that precede INTERFET’s arrival include an account of the extraordinary actions of the 50 unarmed Australian Federal Police officers, accompanied by military liaison officers, who helped protect and oversee the independence vote during some of the worst periods of militia violence as part of the United Nations Assistance Mission to East Timor (UNAMET), and Operation Spitfire, the evacuation of UN and East Timorese staff following the announcement of the results of the independence vote.

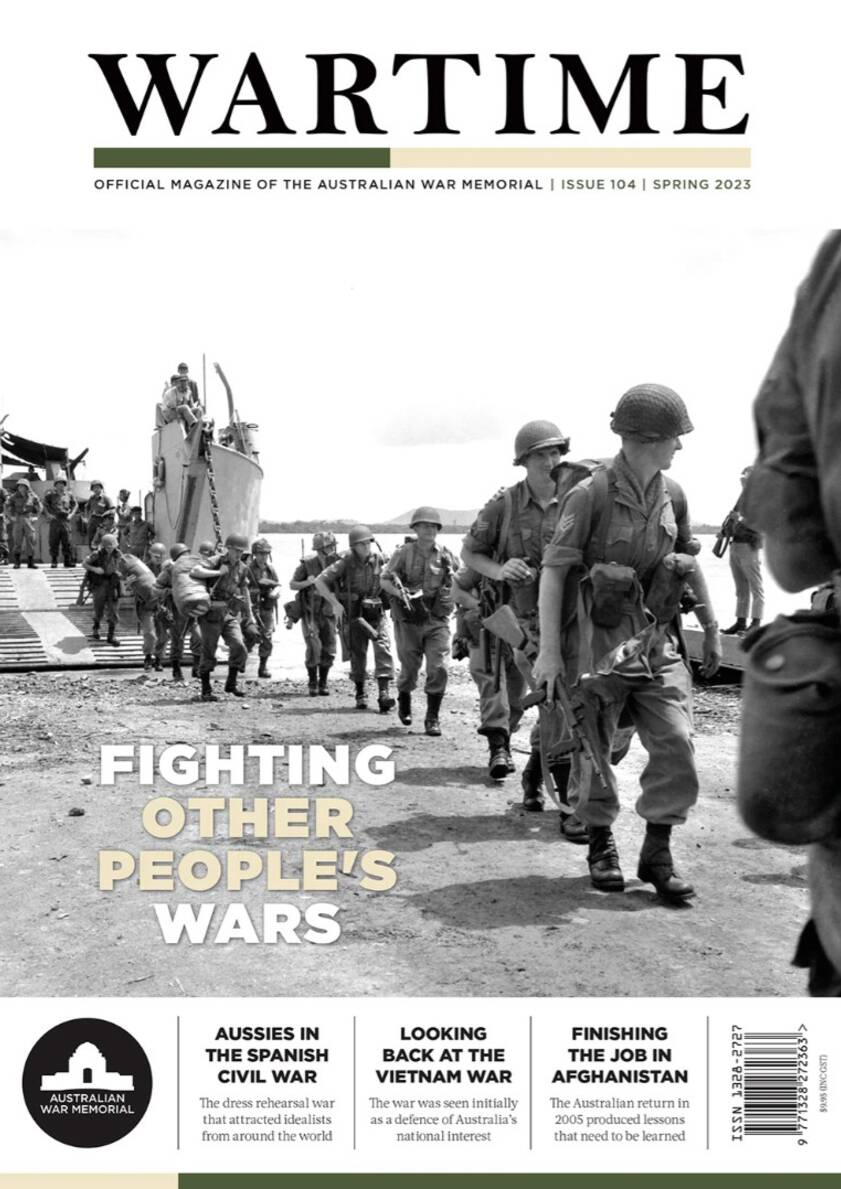

Members of 3rd Combat Engineers Regiment, bound for East Timor, board HMAS Jervis Bay. Photograph: Ray McJannett.

Also included in those 420 pages is a detailed discussion of Australia’s history and often fraught relationship with East Timor – “the pebble in the shoe” as once described by Indonesian foreign minister Ali Alatas. The notion that Australia’s leading role in INTERFET in 1999 was the final expression of Australia’s long-term support for the East Timorese cause has long been brought into question; Stockings’ work leaves such ideas dead in the water. For Stockings, the Australian deployment to East Timor needs to be understood in its complex political and diplomatic context. Successive Australian

governments from the 1970s onwards maintained the position that the plight of the East Timorese people, though desperate, was less important than Australia’s relationship with Indonesia: “The relationship with Jakarta was not going to be sacrificed on the altar of good relations with the East Timorese.” Stockings does not suggest that such a view did not make sense from a long-term strategic sense, but merely points out that it is essential to understand this plain fact of Australian history in order to understand the subsequent deployments to East Timor and why and how they happened. Such a conclusion, in the tradition of all Official Histories published by the Australian War Memorial, reflects the author’s own view, but it is a view well informed by full access to unreleased official records and government documents.

Stockings’ findings in no way diminish the work done by many in the face of great adversity in East Timor, and in many ways the story he tells emphasises the consummate skill, professionalism and ingenuity of Australian personnel in the face of significant institutional difficulties: “The path to INTERFET, like any significant military undertaking, position adopted by successive Australian governments from the 1970s onwards may not shock well-informed readers. John Howard’s December 1998 letter to Indonesian President B.J. Habibie stated, “I want to emphasise that Australia’s support for Indonesia’s sovereignty is unchanged. It has been a longstanding Australian position that the interests of Australia, Indonesia and East Timor are best served by East Timor remaining part of Indonesia.” That letter was put on public display

in the Australian War Memorial in a temporary exhibition in 2019.

Australian troops serving in INTERFET pass a group of East Timorese locals celebrating independence, September 1999. Photographer: Stephen Dupont.

Stockings’ work brings together such publicly available sources and provides a historian’s critical eye, but it does not explode hitherto unchallenged assumptions and narratives. And there lies its strength. It is not so much an exposé as a rational, critical and essential study of an important story for Australians to know and to better understand.

It is a triumph.