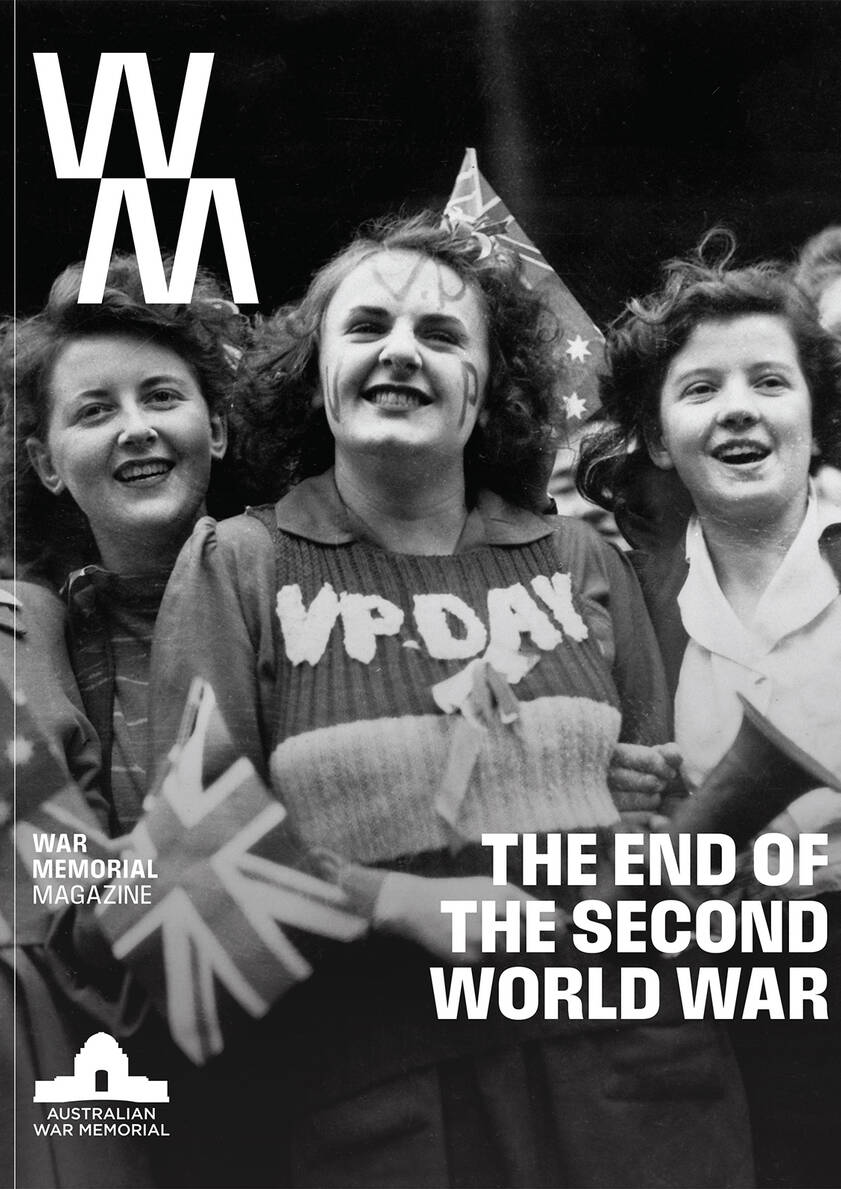

Australian forces were more heavily engaged in 1945 than in any other year of the Second World War – though these campaigns were not without controversy.

During 1944 in the South-West Pacific Area (SWPA), General Douglas MacArthur’s “island hopping” campaign took Americans into Dutch New Guinea and from there to the Philippines. From April 1945 bombing was performed by carrier-borne aircraft. Planning was well underway for an American-led invasion of the Japanese home islands when the war came to a devastating end in August 1945. Until that point, the war in the Pacific had been expected to continue at least until 1946.

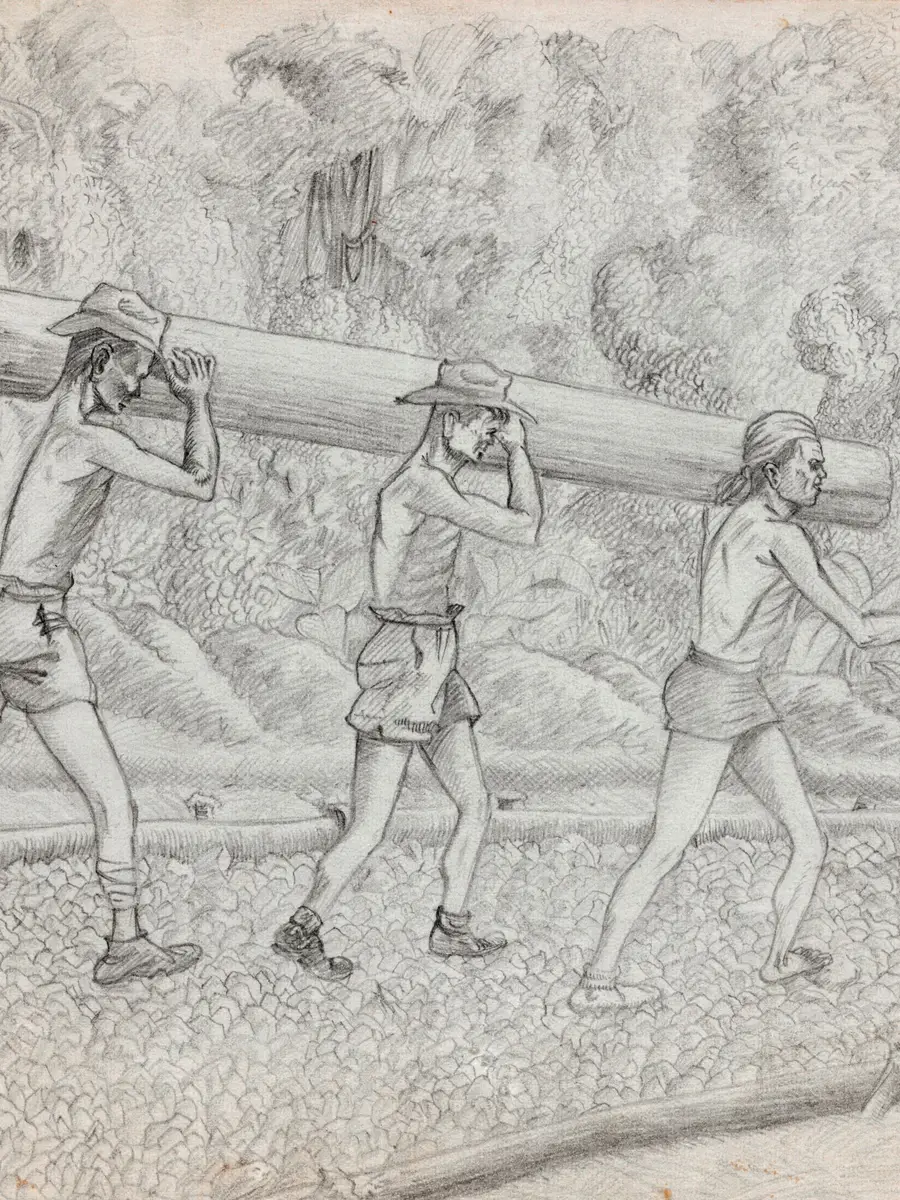

Artwork by Geoffrey Mainwaring, Tanks and infantry, Aitape, New Guinea, 1945.

During the later phases of the Pacific War, however, Australia was left far behind. The Australian army was excluded from operations in the Philippines and beyond. Instead, Australians fought to “mop up” Japanese troops in Australia’s Mandated Territories of New Guinea and Bougainville, and on Borneo. It was also a period of frustration. Australian forces were described as being “whittled away on a more or less ‘face-saving’ task” in the islands. Such sentiments were widely echoed in the press, debated in Parliament, and discussed by the soldiers themselves. Brigadier Heathcote “Tack” Hammer, an infantry commander on Bougainville, later commented:

Every man knew, as well as I knew, that the Operations were mopping-up and that they were not vital to the winning of the war. So they ignored the Australian papers, their relatives’ letters of caution, and got on with the job in hand, fighting & dying as if it was the battle for final victory.

Brigadier Heathcote “Tack” Hammer

Australian troops in Papua and New Guinea had borne the brunt of the fighting in 1942 and 1943, but those long years of jungle warfare were exhausting. As American forces began taking a more prominent role, in December 1943 the Commander-in-Chief of the Australian Military Forces (AMF) General Sir Thomas Blamey directed Australian troops be “withdrawn from an active operational role in New Guinea”. All but two of the six divisions in New Guinea returned home for training and rehabilitation on the Atherton Tablelands in south-east Queensland. MacArthur afterwards stated that it was the Australian success in Papua “that turned the tide of battle and on which all future success [had] hinged” and that Australia’s “brilliant” campaign helped “speed the Japanese defeat in New Guinea”.

Blamey had been anticipating this move. “I think it obvious,” he wrote, “that the operational role of the Australian Forces in New Guinea itself has practically terminated, and therefore any excessive number retained there will be wasted.” There was never any doubt that the Australian army would return to the field. It was only a matter of where, when, and in what strength.

General Douglas MacArthur and Prime Minister John Curtin meet before a conference in Sydney, 7 June 1943. Photographer unknown. AWM139812

MacArthur’s next objective was the liberation of the Philippines; New Guinea was just an obstacle. Rather than assaulting the enemy’s strength directly, MacArthur adopted the strategy of “island hopping”, making amphibious landings on suitable islands and areas that could be developed into bases to isolate and block the Japanese, leaving them to “wither on the vine”. This allowed for speedy advance, but it left large numbers of Japanese troops still occupying territory.

On 12 July 1944 MacArthur sent Blamey a memorandum asking Australian forces to take over “responsibility for the continued neutralization of the Japanese in Australian and British territory and Mandates in the Southwest Pacific Area”.

MacArthur also mentioned the desire to employ Australian ground forces in the advance to the Philippines. Blamey decided to use seven Australian Militia brigades to take over the American garrisons in the islands. This left Australia’s preferred sword arm – the 1 Australian Corps, consisting of the veteran 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions (all volunteer members of the AIF) – available for future operations.

Minimal forces

MacArthur, however, disagreed. After serious discussions, on 2 August 1944 MacArthur issued another directive, stating that the minimal forces to be employed were four brigades on Bougainville; one brigade to cover Emirau, Green, Treasury and New Georgia Islands; three brigades on New Britain; and four brigades on the New Guinea mainland. Australian forces were to take over the outer islands and New Guinea by October, and Bougainville and New Britain by November. The Japanese were thought to number 24,000 around Wewak in New Guinea; 13,400 on Bougainville; and 38,000 on New Britain. (Japanese strength in these locations was actually far greater, with between 35,000 and 40,000 in New Guinea and about the same on Bougainville, making a total of nearly 70,000 Japanese army and navy personnel plus another 20,000 civilian workers in total in these locations. There were another 12,000 Japanese on nearby New Ireland, though these figures were not known until after the war.)

An Australian division consisted of three brigades. MacArthur’s insistence that the equivalent of four divisions be deployed to cover the withdrawal of US troops meant the AIF’s 6th Division had to return to New Guinea. Thus Australian troops began moving to the islands. The 6th Division went to Aitape, on New Guinea’s north coast; the II Australian Corps, consisting of the 3rd Division and two independent brigades, took over in Bougainville and the Solomon Islands; the 5th Division moved to New Britain; while the 8th Brigade, already in New Guinea, remained around Madang.

Blamey decided on a limited offensive in areas where one could be conducted successfully and cheaply. In mid-October, he ordered “offensive action to destroy enemy resistance as opportunity offers without committing major forces”. He elaborated on his earlier orders the following month, explaining that “action must be of a gradual nature” to “locate the enemy and continually harass him, and, ultimately, prepare plans to destroy him.”

The intent was to wear down the Japanese in short, sporadic engagements – not an all-out offensive. What was of overriding importance, however, was keeping Australian casualties to a minimum.

Men from the 19th Battalion prepare for a patrol in the Waitavalo area, Wide Bay, New Britain, 16 March 1945. Photographer unknown. AWM079864

The subsequent Australian campaigns in New Guinea and Bougainville were slow, grinding affairs, fought through swamps, along jungle tracks, and across river crossings and mountain spurs. Air support was minimal, while naval involvement was modest and sporadic. An officer later described the Bougainville campaign as “one long bloody hard slog”.

Relieving the Americans at Aitape in September, the 6th Division began a creeping advance eastwards towards Wewak, the last Japanese stronghold in New Guinea. The advance followed two parallel axes: one along the coast and the other through the mountains. Wewak was captured in May 1945 but resistance in the area continued until the end of the war. In total, 442 Australians were killed at Aitape–Wewak, with 1,141 more wounded.

On Bougainville, the II Australian Corps took over from the Americans at Torokina, on Bougainville’s west coast, in October. From here, the Australian campaign followed three axes: one ran across Bougainville’s mountain spine to the east coast, another followed the coast to the island’s northern tip, while the main push was to the south, towards the main Japanese concentration around Buin. When the war’s sudden end brought the campaign to a close, the Australians controlled about two thirds of the island. Casualties on Bougainville were heavier than on Aitape-Wewak, with 516 Australian dead and 1,572 wounded.

The 5th Division’s approach on New Britain was quite different. Rather than going on the offensive, here the Australians patrolled and confined the Japanese to the Gazelle Peninsula and Rabaul. The Japanese were content to remain where they were and did not try to break out. Australian casualties were far lighter than in the other areas, with 74 men killed or died, and 140 wounded.

Critics have argued the New Britain approach should have also been applied to New Guinea and Bougainville. This would have saved lives – but it would also have committed the Australian garrisons to their islands for an indeterminate length of time.

Moving on

As the war moved further from Australia, so did MacArthur. In September 1944, his Advance General Headquarters moved from Port Moresby to Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea. They were joined by a small group of Australians led by Lieutenant General Frank Berryman, Blamey’s trusted chief of staff. Berryman kept Blamey informed of the mood in MacArthur’s headquarters, observing the ever-increasing marginalisation of Australian forces. Berryman could not get a definite decision from MacArthur’s staff on the employment of Australian ground forces. The liberation of the Philippines began shortly afterwards in October.

The hope that the I Australia Corps would be included in the Philippines was finally dashed on 5 January 1945, when Berryman was told that ten American divisions were sufficient to recapture Luzon, and Australian forces would instead concentrate on Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies. Still smarting weeks later, Berryman complained in his diary:

MacArthur more than once said he would take [the] AIF to Manila with him but now in his hour [of] victory he has not even invited one [Australian] representative to be present – a lack of courtesy to say the least … I have not even hinted that we should be represented as our dignity & pride is proof against inclusion in a flamboyant Hollywood spectacle … In his hour [of] victory his ego allows him to forget his former dependence on the AMF & is in keeping with GHQ policy to minimize the efforts of Australia in SWPA.

Lieutenant Ada McCulloch, 2/5th Australian General Hospital, prepares a penicillin injection, Morotai, 16 May 1945. Photographer unknown. AWM Lieutenant Ada McCulloch, 2/5th Australian General Hospital, prepares a penicillin injection, Morotai, 16 May 1945. Photographer unknown.

Australia’s contribution to operations in the Philippine Islands included significant RAAF and RAN participation, as well as a small number of Australian personnel on the ground. Some 4,000 Australians participated in the liberation of the Philippines and there were several hundred casualties. Navy casualties were notably high, with the cruiser HMAS Australia (II) suffering multiple attacks from Japanese suicide aircraft (see Wartime 68). The contribution of Australian forces to the Philippines campaign has largely been overlooked.

The Australian press, meanwhile, speculated on the Australian army’s whereabouts. There had been no official reports about its activities since the second half of 1944. Nor had news been released regarding the Australian takeover in the Mandated Territories or of offensive operations in New Guinea and Bougainville. Newspapers instead predominantly ran stories about the war in Europe and the Central Pacific.

The Canberra Times’s editor wrote sarcastically: “Will anyone knowing the whereabouts of Australian soldiers in action in the South-West Pacific please communicate at once with the Australian Government.”

On 9 January 1945, MacArthur’s communiques finally mentioned that Australian forces had relieved American forces in New Guinea, the Solomons and New Britain. Only now were the reports and photographs that had been accumulating for weeks published. Despite an initial flurry, the press’s interest quickly waned. By February the campaigns were already beginning to be described as “mopping-up operations”.

A new role

The 1 Australian Corps, meanwhile, continued to languish on the Atherton Tablelands. Things are getting boring, wrote a sergeant in his diary. “Everyone,” he went on, “including the officers, are well and truly fed up.” Another recalled this period as his “worst” time in the army.

A defined role came only in the first quarter of 1945. “My purpose,” MacArthur told Prime Minister John Curtin in March, “is to restore the Netherlands East Indies authorities to the seat of government as has been done within Australian and United States territory.” The American general wanted to liberate areas of Borneo and the Netherlands East Indies. This would be MacArthur’s final task before reporting to the Joint Chiefs of Staff that he had accomplished his purpose in SWPA.

Codenamed OBOE, these operations were intended to have been a series of six amphibious operations with the 6th, 7th and 9th Divisions landing down Borneo’s east coast and moving on into Java, where MacArthur hoped the Japanese would be crushed by early August. Curtin, however, supporting Blamey’s recommendation, refused to release the 6th Division prematurely from its campaign in New Guinea. Ultimately, only three of the six proposed OBOE operations went ahead. In April, the first units from I Australian Corps began moving to Morotai, in the Halmahera islands group, north of Ambon. Morotai became the staging area for an invasion of Borneo. Also based on Morotai was the RAAF’s 1st Tactical Air Force, whose fighter and bomber aircraft had become responsible for air operations south of the Philippines.

“Will anyone knowing the whereabouts of Australian soldiers in action in the South-West Pacific please communicate at once with the Australian Government.”

The Canberra Times editor wrote sarcastically

Blamey’s own policy for aggressive actions in the Mandated Territories was also coming under scrutiny. In May the Treasurer and Acting Prime Minister, Ben Chifley, requested Blamey explain his policy to the War Cabinet, where Blamey offered a clear and well-reasoned appreciation of his strategy. He explained that his policy had been adopted to destroy the enemy where this could be done with relatively light casualties, thus freeing Australian territory and liberating the “native population”, while progressively reducing the military’s commitments and freeing up personnel for release from the army. This was the approach implemented in New Guinea and on Bougainville. On New Britain, where the Japanese at Rabaul were known to be well entrenched and outnumbered the Australians, Blamey’s directive was to contain the Japanese on the Gazelle Peninsula and not to go on the offensive.

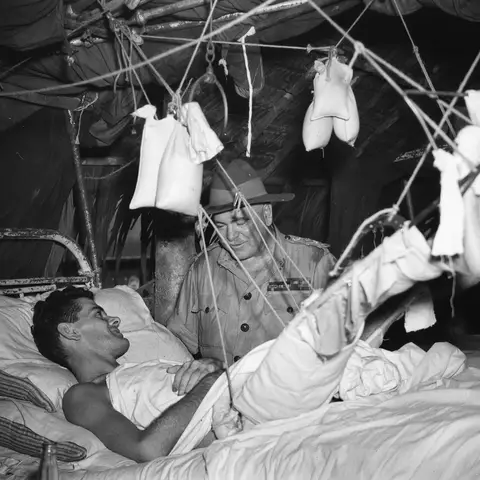

General Sir Thomas Blamey talks with Private H. J. Murphy at the 2/11th Australian General Hospital, Aitape, New Guinea, 20 March 1945. Murphy was a forward scout on a patrol when he was hit by enemy fire. Photographer unknown.

Blamey asserted that the policy of letting the Japanese “wither on the vine” was not working: it tied down large forces in passive roles and was “a colossal waste of manpower, materiel and money”. “We are well into the second year of this policy,” Blamey argued, and “the enemy remains a strong, well organized fighting force.”

The Japanese had become largely self-sufficient, with gardens cultivated by New Guineans and Bougainvilleans. Once the Americans reached the Philippines, Blamey continued, MacArthur had similarly changed his by-passing strategy and sought the complete destruction of the Japanese.

Blamey hoped that by the end of 1945, the twelve brigades in the region could be reduced to five: a division of two brigades on New Britain, one brigade in the Aitape– Wewak area in New Guinea, and one brigade on Bougainville, leaving one brigade in reserve.

In these last two areas, he intended the Papuan and the New Guinea Infantry Battalions and small guerrilla groups to finish destroying the remaining Japanese. Blamey’s argument was presented to the Advisory War Cabinet on 6 June and eventually formally approved at the end of July.

OBOE Two

Another topic discussed by the War Cabinet and Blamey was MacArthur’s plan to use the 7th Division for the invasion of Balikpapan, codenamed OBOE Two. The War Cabinet had previously supported the use of the 9th Division to capture Tarakan Island (OBOE One), on Borneo’s north-east coast, as well as the area around Brunei and Labuan in north Borneo (OBOE Six), as this would increase Allied control of the sea between Malaya and Japan; but there was real cause for doubt over Balikpapan. Blamey recommended the 7th Division be withdrawn from the operation, describing Balikpapan as “a derelict Dutch oilfield”. Indeed, the operation lacked any real object.

Members of the 2/3rd Field Company rest in a landing craft after attempting to destroy beach defences ahead of the invasion of Tarakan Island, Borneo, 30 April 1945. Photographer Norman Stuckey

The American Joint Chiefs of Staff were likewise sceptical, with Admiral Ernest King describing the operation as “unnecessary”. MacArthur, though, would not be denied. He explained to General George Marshall that the operation would not affect preparations for the invasion of Japan, and that all the ground troops involved would be Australians who had been out of action for more than a year.

“I believe,” MacArthur wrote, that if the operation were cancelled or postponed it would produce “grave repercussions with the Australian government and people”. The Joint Chiefs subsequently approved the plan. MacArthur manipulated the Australian government in a similar way:

"The Borneo campaign in all its phases has been ordered by ‘the Joint Chiefs of Staff’ who were charged by the Combined Chiefs of Staff with the responsibility for strategy in the Pacific. I am responsible for execution of their directives … I am loath to believe that your Government contemplates such action at this time when withdrawal would disorganise completely not only the immediate campaign but also the strategic plan of the Joint Chiefs of Staff."

Having been chastened by MacArthur, the Australian War Cabinet endorsed the Balikpapan operation. MacArthur’s bluff had worked.

Activites around Balikpapan Oil Refinery, July 1945

Invasions

The OBOE operations themselves were spectacular and more lavishly supported than any other Australian operation of the war. The AIF was at the peak of its efficiency. The 7th and 9th Divisions were experienced, their soldiers were well trained and drilled in their tasks, and its leaders were battle-hardened. The RAN and RAAF were also prominent in each operation, with vessels from minesweepers to heavy cruisers participating in the invasion. Australian fighters and bombers, including four-engine heavy bombers, were constantly overhead. Each operation was conducted successfully, with skill and bravery.

Men with the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit unload caskets for reburial at Wewak war cemetery, Cape Wom, 23 October 1945. Photographer unknown.

OBOE One took place on 1 May when the 9th Division’s 26th Brigade landed on Tarakan. Despite the copious quantity of firepower available, tough fighting took place in the hills and jungles around the township. It was in this fighting that Lieutenant Tom “Diver” Derrick VC DCM died from wounds.

For many people, the death of a brave, well-respected and much loved soldier epitomises the futility of the Borneo campaign. Worse, the point of invading Tarakan was that its airfields could be used to support later operations – but when taken, the airfields could not be made ready in time. Fighting on the small island was intense until mid-June, with skirmishes continuing afterwards. Altogether, 225 Australians were killed on Tarakan and 669 were wounded.

The rest of the 9th Division landed in Brunei Bay and Labuan Island in north Borneo on 10 June with the task of securing the bay and surrounding area. This was accomplished by mid-July, and for the rest of the war most of the division’s efforts were taken up with civic action, administering and caring for the nearly 70,000 civilians in the area. During this operation, 114 Australians were killed or died of wounds, and 221 were wounded.

MacArthur allocated the 7th Division’s Balikpapan operation an unprecedented amount of air and naval support. Balikpapan was pounded for nearly three weeks in what was the longest pre-landing bombardment for any amphibious operation of the war. The invasion armada numbered over 250 vessels.

Dawn on 1 July revealed what veterans later described as a “terrifying scene”. Clouds of black oily smoke from the bombed refineries blanketed the beach, buildings lay in rubble, and fires burned all along the coast. In the short but sharp fighting that followed, the Japanese resisted fiercely where they could, but within three weeks the town, harbour and surrounding territory were secured, and the Australians were carrying out deep patrols beyond Balikpapan. When the war came to an end a few weeks later, 229 Australians had been killed during this campaign and 634 wounded.

It is beyond question that in 1944 and 1945 Australian soldiers were fighting and dying in areas where their blood and sweat could do nothing to hasten Japan’s surrender.

But this does not mean that these campaigns were an “unnecessary waste”. They were fought in an aggressive manner in order to shorten the campaigns and free up Australian manpower. They were also fought in accordance with the Australian government’s clear desire and intention to see Australian servicemen shouldering such a burden of the fighting as would ensure favourable post-war political positioning. The criticisms and justifications for the later OBOE operations are similar to those for the Mandated Territories, with the Borneo campaign, perhaps more than any other, conducted for political rather strategic reasons. Yet even with the Balikpapan campaign, the government demonstrated Australia’s commitment to MacArthur and honoured the original directive that had established the SWPA.