Sister Betty Jeffrey was a nurse, survivor, record keeper and an author. A prisoner of war in Sumatra for three and a half years; her story stands as a record of survival, endurance, comradeship and courage in the face of great adversity.

The surrender of Singapore in February 1942 was a huge blow to the Allied war effort, with 15,000 Australians taken prisoner by the Japanese.

Sister Agnes Betty Jeffrey, PR01780

Sister Betty Jeffrey was a prisoner of war in Sumatra for three and a half years; her story stands as a record of survival, endurance, comradeship and courage in the face of great adversity.

Professional Nurse Sister Betty Jeffrey enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service on 9 April 1941. She was taken on strength with the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH) and in June arrived as a reinforcement to a hospital in Malacca, Malaya. After the Japanese armed forces successfully invaded the Malay Peninsula, Jeffrey was evacuated to Singapore with the 2/10 AGH.

By February 1942 Singapore was falling, and amidst the chaos of shelling and bombing, the nurses were ordered to evacuate to Australia. This created grave misgivings among the nurses, as injured troops were continuing to come in. The first group of nurses to be evacuated sailed aboard the Empire Star on 11 February and reached Australia, despite being bombed and harassed by the Japanese.

The remaining 65 nursing sisters, including Jeffrey, left Singapore aboard the Vyner Brooke at 6 pm on 12 February. This was just three days before the surrender of Singapore on 15 February 1942.

“I write in retrospect – keeping a watchful eye out for the Japanese guards who wander in and out of our houses all day with fixed bayonets – with a precious stub of pencil in an exercise book I managed to scrounge from the guard-house.”

White Coolies

Sinking

Aboard the Vyner Brooke there were 181 civilians and nurses. The ship usually carried only 12 passengers in addition to its crew, so it was overloaded and very short of supplies. The only food and water aboard had been brought in by the nurses. After two days at sea, sailing close to the islands to avoid detection, the Vyner Brooke was discovered by a Japanese aircraft near Banka Island. It swept over the ship during the day, strafing and damaging the life boats, but did not return. The next day the Vyner Brooke was again under attack from the air, and this time they were dive-bombed. The nurses and civilians were raked with machine-gun fire and struck by bombs, one of which went down the ship’s funnel, sinking the ship.

The nurses were told to ensure that all the civilians were off the ship before they evacuated. Jeffrey recalled having to push overboard some civilians who were frozen in fear. At the very last, when the ship was rolling onto its side, Jeffrey leapt into the sea. She later wrote that they were all advised to jump overboard shoeless to aid swimming: “I’ll never do that again – I’m still shoeless.” She tried to use a rope to ease herself down to the water, ‘Tarzan style’, but the rope tore her hands very painfully.

Jeffrey recorded that the nurses offered considerable support to each other in the water, including helping Matron Olive Paschke, who could not swim. The nurses also engaged in impromptu meetings in the water “to organise things a little better”. Jeffrey and nurse Iole Harper ended up on an overcrowded raft that was sinking under the weight. They decided, being strong swimmers, to get off the raft and swim alongside it towards land that was only a blur in the distance. The two nurses were in the water together for a whole day before they thought to introduce themselves.

Iole was about fifteen yards ahead of me when suddenly she turned round and called out, ‘Oh by the way, what’s your name?’ We had been swimming together for twenty-eight hours! So we paused, while we formally introduced ourselves, looked each other over, and exchanged names and addresses. As we belonged to different units, we had never met before.

As they attempted to get to shore, the raft was suddenly pulled by a current out to sea. Those on board the raft, including Matron Olive Paschke, called to Jeffrey and Harper; but the occupants of the raft were never seen again. Jeffrey and Harper ended up spending three days in the water, swimming up streams and getting lost in mangroves. When the tides were going out they climbed the mangrove trees and also attempted to sleep in those trees. Jeffrey and Harper eventually met some Malays who helped them with food, and a Malay nurse dressed their wounds; but hiding the two Australian nurses was too great a risk for the civilians. When they heard that there were other nurses being held by the Japanese as prisoners of war, Jeffrey and Harper decided to give themselves up.

Given their situation, it was not an easy decision. After the sinking of the Vyner Brooke twelve nurses were never seen again, assumed drowned. Twenty-two other nurses made it to Radji Beach on Indonesia's Banka Island; there they surrendered to the Japanese, but were massacred by machine-gun, with only Vivian Bullwinkel surviving. Thirty-one other nurses, including Jeffrey, swam, floated and made their way to shore and became prisoners of war. Jeffrey had originally heard that the Japanese were not taking prisoners. She expected to be shot, but was taken to a jail at Muntok, the capital of Banka Island, and was delighted to rejoin the surviving nurses.

Days later, just before they were moved, Vivian Bullwinkel came to join them. She told them about the massacre, a story the nurses kept secret throughout the war. Jeffrey later recalled that sleeping on a concrete slab in the jail was luxury compared with what was to come; but even then, “It was water, water, water that we needed ... throughout our whole internment – we never had enough.”

Sisters Thelma Bell and Betty Jeffrey while serving with 2/10 Australian General Hospital, Malacca, Malaysia c 1941. AWM PR01780

Sister Jean Keer (Jenny) Greer (left), and Sister Betty Jeffrey recovering from malnutrition in the Dutch hospital. 1945. Photographer unknown.

Making a record

During three-and-a-half years of captivity on Sumatra and Banka, Jeffrey recorded her experiences on paper that she was able to scrounge or procure. The first notebook she obtained was from a trader who came in with food and materials, sold to the prisoners at steep prices. Jeffrey soon filled the pages. At this stage the Japanese seemed not to be concerned about prisoners writing. Jeffrey scrounged the second book from the Japanese. “I remember going out on a working party and I saw a little blue exercise book in a guard house and I thought I just want that – the guard wasn’t looking and I grabbed it – he didn’t catch me.” At first Jeffrey just kept the diary among her belongings, but after inspections started, she began hiding it.

Pencil used by Sister Betty Jeffrey to record her experiences as a prisoner of war.

Conditions had vastly deteriorated by 1944. The nurses were moved to a dirty, mosquito-ridden place below sea level. Rations were very low and disease was taking lives. Keeping records became forbidden and if any were discovered, it would be at great personal risk of punishment. Jeffrey had been hiding the diaries in a pillow that she had made from local kapok.

At one point an officer ordered all paper records – everything in writing, including personal letters, marriage certificates and other papers – to be burnt. Jeffrey had been keeping the diary for nearly two years; she decided to take the risk and hide it. She rolled up her two exercise books and hid them under the bench where she slept. The diaries were placed in a beer bottle with its top broken off, and hidden under there with the spiders. And there they stayed for several months.

When the nurses were moved back to Banka Island in 1944, Jeffrey made a little pouch from a fish bag for the diaries. She tied it around her waist and wore it inside her shorts. The nurses were being moved in a small junk with kerosene sloshing around its floor; they were sitting in this highly flammable liquid during an air raid. Their passage was only 100 yards but it felt endless; Jeffrey began to feel very unwell and loosened the diary pouch round her waist. When she got off the boat she realised the diary had fallen off and she thought that she had lost it forever. However, a Japanese found the bag and was calling out, whose is this? Jeffrey put her hand up and he gave it to her – without looking inside the bag.

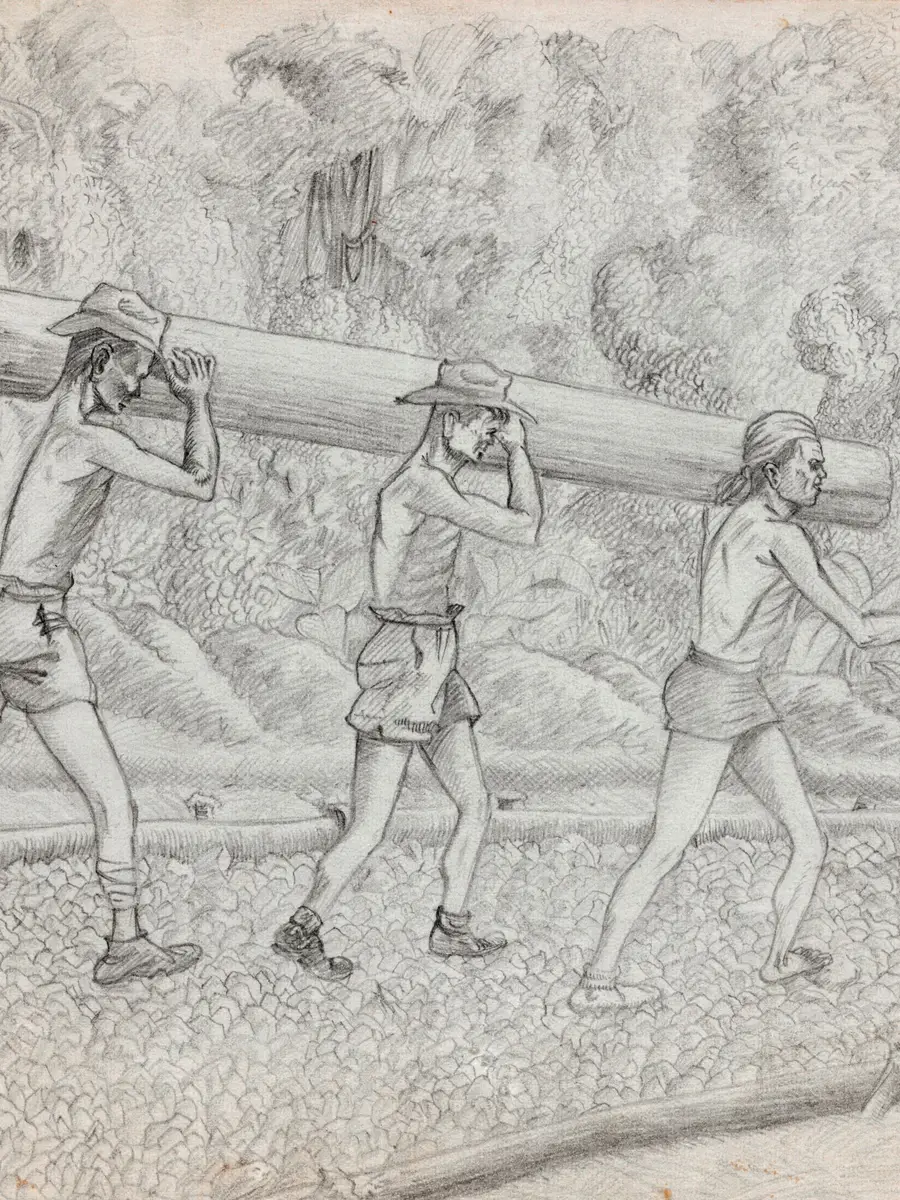

Jeffrey continued to record her experiences on scraps of paper when her notebooks were hidden. The diaries are a record of how the nurses survived. Jeffrey was starving and recipes are a strong feature. She drew many sketches depicting camp life, including the various jobs she needed to perform to survive, such as water carrying, wood chopping, making bread from ground rice – as well as making Majong sets and cutting hair. Jeffrey was the local hairdresser and used curved nail scissors for 10 cents a haircut. She recalled a woman from Java whose thick curly hair took four days to cut.

Music

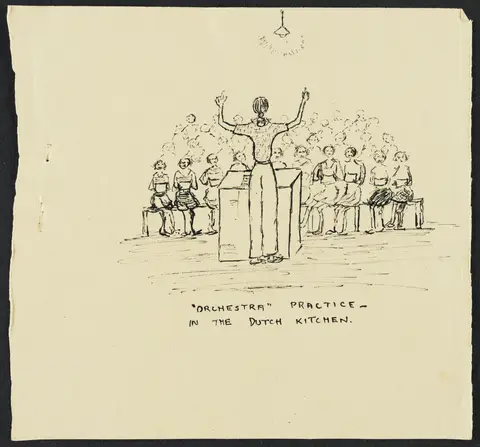

Ink drawing by Betty of orchestra practice

During 1944, Jeffrey joined the Women’s Camp Orchestra, and among her papers held at the Australian War Memorial are her copies of the music that the choir performed. In her memoir White Coolies she described the music as being the most wonderful thing that had happened to the camp. "The music is written on any type of paper obtainable, each person has her own copy all copied from Miss Dryburgh’s hand-made original.” Miss Dryburgh, a British missionary, wrote the music for the choir from memory, and the women used their voices as musical instruments.

Among Jeffrey’s music is a sketch depicting waving hands and barbed wire. This sketch was drawn at House Two, the only place where women could see their relatives in the men’s camp. The women would wave to the men in the distance each morning and evening. In White Coolies Jeffrey relates that on Christmas day they sang to the men "O come, all ye faithful”. She describes how the men stopped and listened and waved hankies, shirts and hats, and an echo of thank you was also heard. Two days later, when the men sang the same song back to the women, she noted, “Everyone wept.”

The end of the war

I have written this diary spasmodically for three and a half years, but now it is written almost hourly because good things are happening so quickly. Hell has turned into heaven almost overnight. Thank goodness the diary does not have to be hidden anymore, it looks like a wreck.

The end of war.

24th August 1945!

The war is over. Who will be first here to take us home?

We are free women!!

The nurses who became prisoners of war following the shipwreck had no resources, yet by war’s end they had a higher survival rate than the civilian internees. Sister Wilma Oram said in an interview, “We stuck together and relied on each other as a group ... in the camp we all supported each other.” This camaraderie, as well as their professional knowledge and skills, helped sustain them through three and a half years as prisoners of war. Staff Nurse Florence Trotter said, “That’s why we came home, because we helped each other in the camp ... we kept each other going.”

Betty Jeffrey required two years of hospitalisation to rebuild her health. Of the 120 Nurses in the 8th Division who served in Malaya, 41 never returned. In 1948 Vivian Bullwinkel and Betty Jeffrey travelled to Victoria to raise funds to establish an Australian Nurses Memorial Centre in Melbourne in their memory. They travelled in Jeffrey’s car and spoke at public meetings in every town in Victoria that had a hospital with more than 20 beds. They raised a considerable sum, and the Memorial was established by Jeffrey at 431 St Kilda Road in Melbourne. Jeffrey managed the centre for five years until ill health forced her to retire.

Betty and Vivian Bullwinkel during their London visit.

In 1951 Vivian Bullwinkel and Betty Jeffrey were presented to King George VI at his last court at Buckingham Palace. Jeffrey continued to work as a guest speaker and lived into her 90s, but she never fully recovered her health. She published White Coolies in 1954, based on her forbidden diaries. The story of the camp orchestra was dramatised in the 1997 film Paradise Road, for which Jeffrey was a consultant. Betty Jeffrey donated the majority of her papers to the Australian War Memorial in 1952. The sketches and music were donated by her family in 2000 and 2001.