Already a hero of the Antarctic, a gifted man’s life was wasted at Gallipoli

A prize-winning student, athlete, explorer and soldier, Bob “Badget” Bage was killed during the first fortnight of fighting on Gallipoli. The nation could ill-afford to lose this young hero, whose death seemed to have been so unnecessary.

Studio portrait of Lieutenant, later Captain, Edward Frederick Robert Bage, 3rd Field Company Australian Engineers, 1914.

Edward Frederick Robert Bage was born into an educated and socially aware Melbourne family in 1888. His father, who died when he was four, had been a wholesale chemist and a keen amateur scientist. Bage had two older sisters; one, Anna, was a pioneer of her age and became famous as a scholar and a worker on a wide range of women’s issues. After graduating in civil engineering, Bage joined the militia and was commissioned second lieutenant in 1909.

Two years later he transferred to the regular forces and was appointed a lieutenant in the Royal Australian Engineers. Shortly after that, aged 23, he took leave to accompany Douglas Mawson’s 1911 Australasian Antarctic Expedition as astronomer, assistant magnetician and recorder of tides.

During that famous expedition, Bage led the southern sledging party on a perilous 1,000-kilometre overland journey towards the region of the magnetic pole. For weeks on end the group encountered blizzards, freezing temperatures, snow-blindness and frost-bite. Their return, with dwindling rations, became a race for survival. Elsewhere, Douglas Mawson’s far-eastern party struck disaster, leaving him the sole survivor of his group.

Back at base, Bage was one of a handful of volunteers who remained behind to wait for Mawson after he failed to return in time for the expedition’s sailing. Ice and weather closed all access to the base until the next summer. Mawson did get back after surviving an extraordinary ordeal and when hope had almost been given up. Mawson, Bage and the others endured another winter before the relief ship could return for them.

An Antarctic colleague, Charles Laseron, gave a fond description of Bage:

I can picture Badget still, with his stocky figure, thinning hair, and an old pipe. His pipe was part of him, and he had it in his mouth even when not smoking. He was always cheerful, ready with a hand to anybody who needed it, yet he was one of the quietest members of the expedition. When he did a job he set about it with a quiet thoroughness that was characteristic, and the job when done needed no improvement. He was a born leader of men.

The outbreak of the war in 1914 seemed to offer fresh adventure for the young military officer. With his keen sense of duty, he quickly transferred to the AIF for overseas service.

He was commissioned as second-in-command of the 3rd Field Company, Australian Engineers, and sailed from Melbourne on the troopship Geelong on 22 September 1914. Several months later, after training in Egypt, he was present at the landing at ANZAC on 25 April 1915.

On 7 May Major General William Bridges, commanding the Australian division, visited the front-line positions of the 11th Battalion near Lone Pine. The general decided that a trench needed to be dug further forward, and ordered that an officer of engineers go out to establish the best spot and mark it with pegs so that digging could be done later under the cover of darkness. Captain Bage happened to be nearby. “Here’s the man,” exclaimed Bridges, promptly ordering him to do the job.

Bage and others could see that this work, to be done in broad daylight in an exposed and unprotected position well in front of the Australians’ trench line, would be under the noses of five Turkish machine-guns. Sapper James Campbell was there. He later wrote: “Captain Bage [was] ... a very fine officer. He knew he’d probably not come back, but the work had to he done, and like Captain Oates of Scott’s expedition - ‘he went out like a very gallant gentleman’.” The task began about 3 pm. Bage was hammering in a peg when the machine-guns opened up on him. He was immediately hit in the shoulder. There were attempts to get him back to shelter, but the fire was heavy. Bage was soon hit again in the leg, and then through the head.

He was dead. The gallant officer’s body was left, out of reach, until nightfall, when it was recovered and taken to the beach for burial. Colleagues prepared a white wooden cross and put it over the grave.

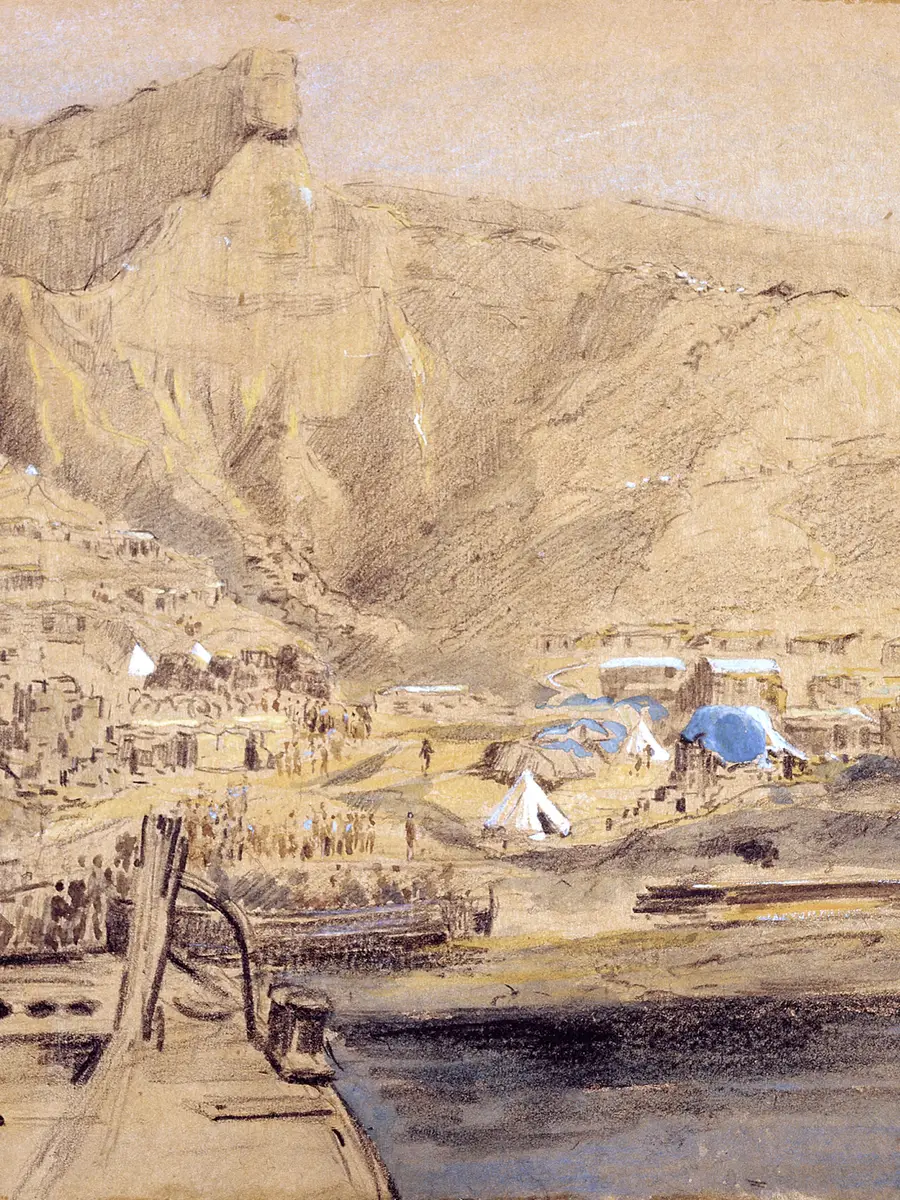

The cemetery near Hell Spit on the southern horn of ANZAC Cove. The grave on the left is that of Captain Bage.

After Bage’s tragic death, the foolish idea of digging the trench on pegged-out lines in such an exposed position was promptly dropped. It is hard to see that Bridges was anything other than wasteful of the young officer’s life in giving him the perilous task. Charles Bean, the official war historian, was an admirer of Bridges and provided some weak justification, saying that the general “did not ask of Bage more than he himself would have performed”. But the comment provides poor consolation, as Bridges had a reputation for being careless under fire. Some felt that this led to his own death too, when he was mortally wounded by a sniper a week later.

Bob Bage’s mother and sisters were shattered by the news of his death. He was never forgotten in their lifetimes, and they established scholarships in his memory. Later, when a package of his small possessions was made up to send to the family, among the selection of a dozen minor personal articles listed were poignant entries for “1 medal ribbon” and “1 pipe”. The pipe was no doubt a favourite, and the ribbon a reminder of other times. It must have been the white ribbon for the remarkable band of Antarctic explorers who were holders of the rare Polar Medal.