The role of women in espionage is a missing dimension in the history of D-Day.

It has been more than 110 years since the formation of the British Secret Service in 1909. Yet there has been no comprehensive account of women in intelligence, even though women were at the heart of some of the most important intelligence operations of the twentieth century.

They have been the missing dimension in intelligence history, as well as in wider narratives of the Second World War and especially the D-Day operations. There have been exceptions, where the stories of women have received much research attention; these are the women at the code-breaking site, Bletchley Park, and the female agents dropped into France with the Special Operations Executive (SOE). This incomplete picture of war, and especially D-Day, is now changing through the work of contemporary female historians.

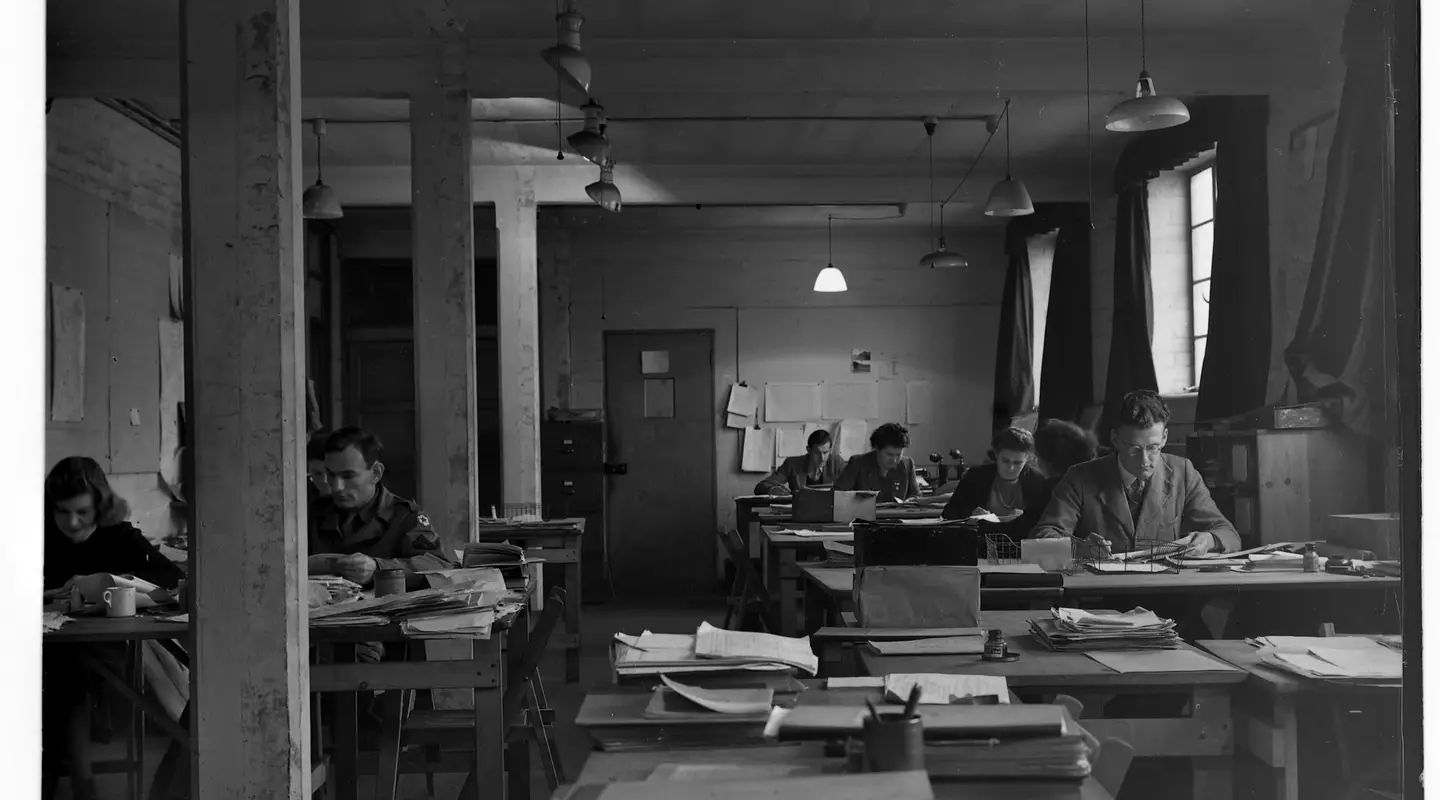

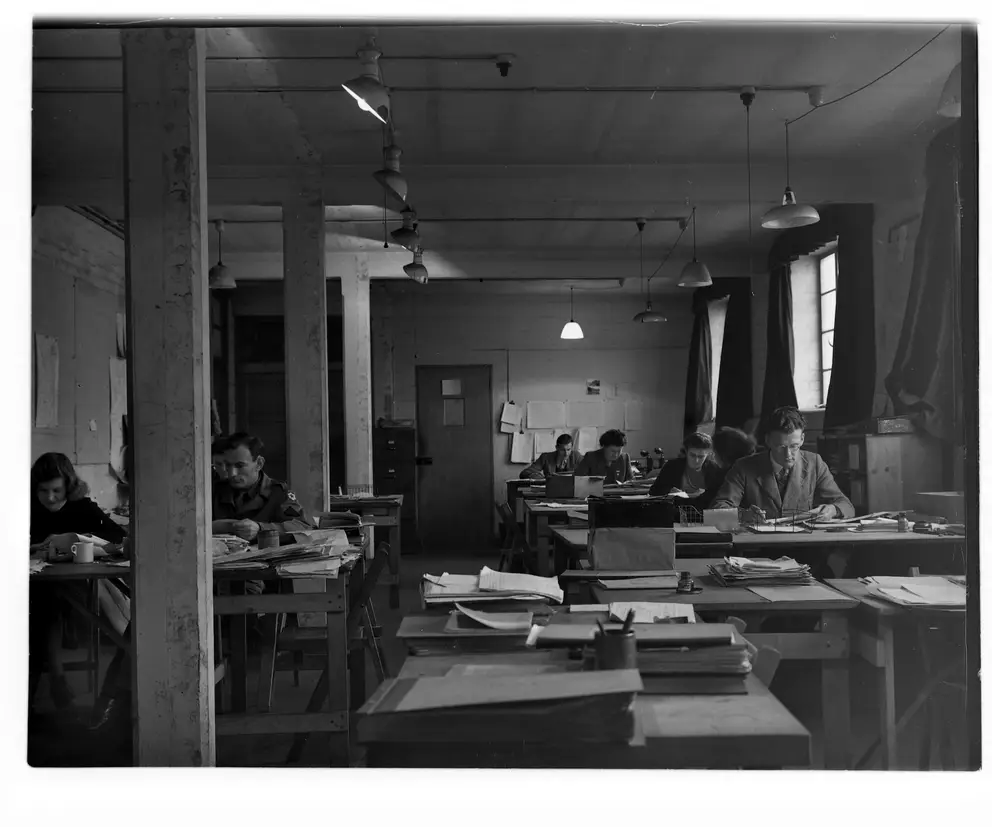

Bletchley Park where women carried out vital work as codebreakers and cryptanalysts. Image courtesy of Government Communications Headquarters.

Despite the prejudice that existed against them, women found their way into a wealth of roles across the intelligence spectrum, in civilian organisations and in uniform, as code-breakers, spies, couriers and analysts. A closer look at these roles shows that they were, in fact, at the heart of intelligence operations on Britain’s home front and also in enemy occupied countries from the outbreak of the Second World War to its end, and beyond.

In operational intelligence, they were engaged behind enemy lines in intelligence gathering, deception and sabotage. Strategic and support intelligence relied on women who provided analysis of aerial photography, radio communication, code-breaking and interrogation. Historically, in “both operational and support intelligence there has been a remarkable, albeit painfully slow, recognition of the capability of women to successfully gain intelligence,” as British Brigadier Brian Perritt has acknowledged.

Before D-Day

Intelligence planning for D-Day began at least a year before the landings. By mid-September 1943, planning began for D-Day (codenamed Operation Neptune) the following year. The workload produced an increase in intelligencers, especially women, across a number of sites in the UK, including at the Admiralty in London.

Section 8K at the Admiralty carried out analysis of incoming Ultra traffic (cryptographic signals intelligence) and phoned the latest dispositions to the relevant naval bases and departments. From 1943, intelligence Section 8K was run almost entirely by women. That year, a young Miss Lee joined the section and was placed in charge of all intelligence on harbour defence activities between Cherbourg and le Havre on the northern coast of France.

It was here that the most detailed information would be needed because the Allies intended to land their invasion forces on the beaches of Normandy. It meant that a woman, Miss Lee, was responsible for all Naval intelligence in the region of the D-Day landings. She is one of many examples of female personnel in Naval Intelligence who overturned the conventional ideas of women’s roles. She demonstrates that women’s office roles were not restricted to secretarial and confidential filing.

Agent Gabrielle de Monge who worked behind enemy lines in Belgium in WW1. Image courtesy of Government Communications Headquarters.

During the critical months of 1944, as many as 15 people worked in Room 30 at the Admiralty, the nerve centre of naval operational intelligence on D-Day; most of them were women. The quality of intelligence produced there depended on the sheer mental and physical stamina of the personnel in Room 30.

In 1944, everything was subordinate to Operation Neptune. At the aerial intelligence analysis centre, RAF Medmenham at Danesfield House near Marlow, north of London, G Section was one of the most important sources of intelligence, as it was responsible for detection of the enemy’s wireless technology – both its offensive and defensive radio systems.

Before D-Day, the work of this section, which included women, was vital in locating German radar equipment around the invasion beaches of Normandy. Their preparation work meant that the Allied forces that landed on 6 June 1944 by air and sea did so without prior detection by the Germans. Not only did this enable a successful invasion, but it prevented a greater loss of Allied personnel.

There was no pause in the volume of traffic coming from sites like Bletchley Park.

Codebreakers Mavis Batey and Margaret Rock played a leading role in cracking the complex Enigma code of the Abwehr (the German Secret Service). On 8 December 1941 Mavis had broken a message on the link between Belgrade and Berlin. Within days, codebreaker Alfred ‘Dilly’ Knox and his team had broken into the Abwehr Enigma coding machine (that is, broke its code), and shortly afterwards, Mavis broke a second Abwehr machine. The significance of their work cannot be overestimated, because although it was nearly three years before D-Day, their work laid the ground for what was to come for D-Day, especially in supporting the running of double agents.

Senior female staff of Registry section of MI5, 1918,_pictured with Lieutenant Colonel Maldwyn Haldane

Female agents

MI5 and MI6 were running a number of double agents as part of the Double Cross System that fed deception and fake intelligence to the Germans. Being able to decode the messages between the Abwehr and their agents ensured that the double agents really were working for the Allies, and it provided a way to monitor whether the Germans had accepted the British deception.

This was vital in the deceptions ahead of D-Day – such as the famous Operation Mincemeat, that floated a uniformed body off the coast of Spain in 1943, carrying fake invasion plans to fool the Germans that a landing was imminent in Greece, rather than in Sicily and Italy. The success of the double agents in this operation meant that other deception plans could be initiated in the months leading up to D-Day, 6 June 1944.

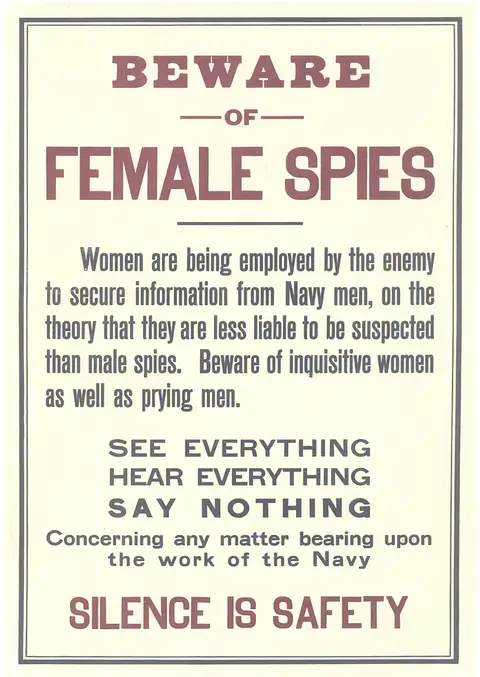

Poster warning about Germany's use of female spies in the UK to charm secrets from men of the Royal Navy. Image courtesy of Government Communications Headquarters.

A wealth of books has been written on D-Day operations, including the deception plans leading up to D-Day. But these narratives focus almost exclusively on the men, so that the role of the female double agents in vital deception in preparation for D-Day has been missing from the accounts. There were real dangers facing the Allied preparations. In April 1944, Heinrich Himmler replaced Admiral Canaris as chief of the German Secret Service. The Twenty Committee that ran the Double Cross was concerned that Himmler’s efficiency and ruthlessness could unmask weak spots in its system during the crucial period before D-Day. The danger came from German spymasters and intelligence officers operating on the Iberian peninsula, who began to realise that Germany was going to lose the war and that they should re-insure themselves by coming over to Britain to impart information personally to their agents.

The female double agents working for MI5 and MI6 were critical in deceiving the German secret service at this time of Double Cross’s greatest vulnerability. The double agents convinced their German handlers of the reliability of the intelligence they were being given, with the result that the German spymasters did not, in the end, travel to the UK to shore up their operations. This enabled the masters of the British Double Cross to deliver its greatest deception plans to safeguard D-Day.

The main deception by British intelligence before D-Day was codenamed Plan Bodyguard, and was designed to mislead the Germans into believing that the invasion would take place at the Pas de Calais in northern France. At the forefront of Plan Bodyguard were the male agents known as Garbo, Tricycle, Brutus, Mullet and Tate. Garbo was running an organisation of fake German sub-agents with great efficiency and panache, leading the Germans to believe that he had a real network of agents. Brutus built up a false order of battle for D-Day, which the Germans believed. Heavily supporting their male colleagues were the female agents Bronx, Gelatine and Treasure, but they have received little attention.

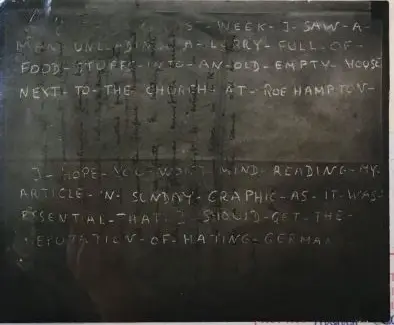

Bronx

Bronx’s real name was Elvira Concepción Josefina de la Fuente Chaudoir. She was 29 years old, the daughter of a Peruvian merchant. She spoke fluent French, English and Spanish and had joined the Double Cross system after having already worked as an MI6 agent. Gelatine was originally an Austrian whose real name was Friedl Gärtner. She went on to feed deception and snippets of gossip about British society to her German handler in Lisbon. Treasure was Nathalie Lily Sergueiew, a French citizen of Russian origin, who was sent by the Double Cross to Paris to pass deception to Major Emile Kliemann of Luft I (the Luftwaffe intelligence service). There were a number of other female double agents, all of whom corresponded with their German handlers using the traditional spycraft of invisible ink.

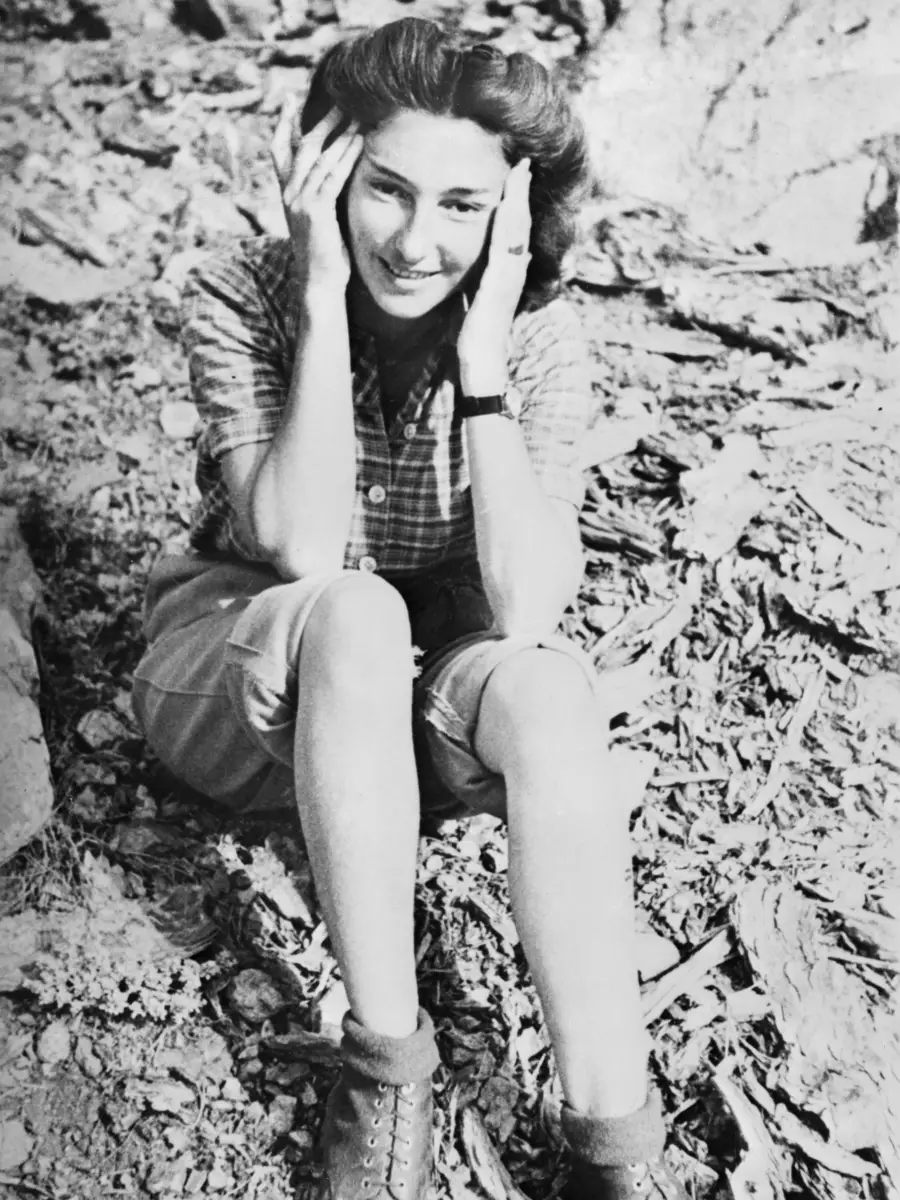

Ecclesiastic, female double agent in Lisbon on behalf of the Double Cross. Image courtesy of Government Communications Headquarters.

But it is Bronx who should be singled out here, because her most important work occurred immediately prior to D-Day as part of Plan Ironside. Her exclusive role was to convince the Germans of an attack at Bordeaux, a port city on the French Bay of Biscay, rather than the Normandy beaches.

Her deception plan was put into action in the second half of May 1944. The Germans expected her to report on any sign of British troop movements for an invasion. She was given a code to indicate where the landings would take place, and was to send a coded telegram asking for a sum of money for her dentist.

The amount asked for would indicate to the Germans the location of the invasion. If a landing was to occur in Northern France and Belgium, she was to ask for £70. For Northern France and Bay of Biscay, it was £60, the Bay of Biscay £50, the Mediterranean £40, Denmark £30, invasion in Norway £20, and the Balkans £10. In case of multiple invasion points she was to wire a message, for example, ‘send £30 plus £80, and the rest as soon as possible,’ which meant that an invasion was to take place in the Atlantic and Denmark.

She improved her credibility with the Germans by extending her code to include payment for her doctor and her physician, as well as her dentist.

As part of Plan Ironside, Bronx sent a series of carefully timed telegrams to her German handler in Lisbon, knowing the telegrams would take about 14 days to reach the Iberian Peninsula. The first asked for £70 to be sent to her to pay for medicine. This was the code that an invasion was expected against Northern France and Belgium on an undetermined date. The following day, she sent a second telegram asking for £50 urgently to pay her dentist, to be paid within a fortnight of the first remittance. She wired to Lisbon (in translation): “I have definite news that a landing will be made in the Bay of Biscay in about one month, i.e., about 15 June.” Bronx told them that the information had come from an intoxicated friend, an officer who had been informed that an airborne attack on Bordeaux would happen on 15 June.

That fictitious date was nine days after the real invasion of Normandy. Bronx strengthened the story by telling the Germans that on the following day the officer was worried about having breached his security and had asked her not to tell anyone. The Germans believed her. They immediately authorised a payment of £50 in addition to her regular payment of £100 per month. The extra money was believed to be possibly a bonus because of the value of the Plan Ironside material, or in recognition of the general excellence of her traffic (information) at that time.

Bronx’s communications deceived the Abwehr that the Allied landings would take place in the Bay of Biscay rather than on the Normandy coast. The result was that on D-Day the Germans held back the 11th Panzer Division in the Bordeaux area and did not send it to reinforce their forces in Normandy. This prevented a greater loss of life for the Allied forces than actually occurred during the landings. It was a magnificent strategy, because the Germans continued to believe Plan Ironside well after the first landings had taken place on the Normandy beaches. This fact was verified by a number of sources: Special Intelligence, captured documents, and statements by German generals at MI19’s clandestine eavesdropping site at Trent Park, north London. Plan Ironside split German forces before D-Day and saw troops retained, not only in the Bay of Biscay but north of the Seine, for a prolonged and vital period.

Invisible ink writing by Bronx, the female double agent who decieved the Germans ahead of D-Day

After D-Day, Bronx and other double agents continued the strategic deception by hinting at a second invasion, informing the Germans that the landings in Normandy represented a small force compared with the vast armies waiting to invade in a second wave at a different location, probably Calais. Bronx passed false information to the Germans about liners repeatedly crossing the Atlantic filled with American troops, and saying that these reinforcements were part of an Allied global strategy.

There was a long road ahead for Allied troops fighting in Europe. Successful advances by Allied forces through Normandy after D-Day proved unexpectedly slow. The deception work of the double agents, including the women, continued to be used as support for the Allied forces as they liberated the rest of France, Belgium and Holland, and headed for the invasion of Germany.

Before D-Day and beyond, women were a vast, hidden workforce of intelligencers, codebreakers, spies, secret agents, handlers and double agents whose enormous contribution to the secret world of intelligence has been eclipsed by men, but also by official secrecy. Even when the files have been declassified, there has been a tendency to glamourise the female spies and a reluctance to discover their true stories. That is now changing as historians begin to focus on the hidden dimension of women in intelligence, in particular, and more widely within conflicts. What emerges is a complex picture, and one across all aspects of the British secret services.

Today, declassified files and other archives make it possible to begin to restore many of the often-nameless women of intelligence to their rightful place in history. It is hoped that the hidden hand of the female intelligencers and double agents behind D-Day will be reclaimed in this 80th anniversary year.