War can be surprisingly difficult to define, particularly when notions of war change over time: for example, the Frontier Wars.

From the distant past to today, the nature of war appears to be constant: it is an act of violence to impose one’s will on an adversary. But as the word war is used to refer to almost every form of conflict and competition – from trade wars and supermarket wars to wars on poverty, drugs, whistleblowers, and disease – how do we meaningfully decide what is war in the military sense, and what is not? A basic, broad definition of war as “armed conflict between groups” includes forms of conflict that most people would not classify as war – fighting between organised criminal gangs, for example, or disorganised feuding with makeshift weapons.

Attributed to Wilhelm Wach, Carl von Clausewitz, c. 1830.

Military theorist Carl von Clausewitz’s book On War (1832) contains the most frequently cited definition of war. Arguing that war is “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will”, Clausewitz made the well-known formulation that war “is merely the continuation of policy with other means.”

Australian international relations expert Hedley Bull provided a similar focus, defining war as “organised violence carried on by political units against each other. Violence is not war unless it is carried out in the name of a political unit; what distinguishes killing in war from murder is its vicarious and official character.”

The contemporary definitions of war used by the Australian Defence Force reinforce the connection between group conflict and political aims. ADF-C-0 Foundations of Australian Military Doctrine describes “the nature and character of war” as “the use of violence to achieve a political objective on behalf of a society.

Societies undertake war where they judge that force is necessary to compel an adversary. Given that war serves a political purpose, it is undertaken in the context of, and in coordination with, a range of other policy.”

Each of these definitions broadly describes war as “organised violence conducted for political purposes”. Given this broad agreement, surely differentiating war from other forms of conflict should be relatively uncomplicated. Both world wars are easily identifiable as wars, as are the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan in the early twenty-first century. In the Australian context, however, the notion of “Frontier Wars” still attracts public debate.

Recognising the Frontier Wars

The term “Frontier Wars” (sometimes called the “Australian Wars”) refers to violent conflict between Indigenous Australians and settlers (primarily British), starting with the arrival of colonists in 1788. Warfare followed colonisation as it spread, beginning around Sydney and not reaching northern-central Australia until the early 20th century.

Although not a new concept, the idea of the Frontier Wars has found increasing public acceptance in recent decades. In 2020, a survey conducted by Reconciliation Australia asked respondents their opinion of the statement, “Frontier wars occurred across the Australian continent as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people defended their traditional lands from European invasion.” Among respondents, 64 per cent of non-Indigenous Australians agreed with the statement, with 30 per cent unsure, and six per cent disagreeing.

As the survey results demonstrate, disagreement and debate remain about whether conflict between Indigenous Australians and settlers was “real war”. A well-worn argument is that there were not enough deaths on either side to constitute a war. War deaths are not usually used in defining whether conflicts are considered a war, although the Uppsala Conflict Data Program defines “armed conflict” as fighting with more than 25 battle-related deaths.

Recent research by historians has challenged the assumption that few deaths during the Frontier Wars were caused by armed fighting or battles. There are also questions about why a certain number of deaths is required to legitimise the use of the word ‘war’ for the Frontier Wars, but not for other wars that Australians have been involved in.

The Colonial Frontier Massacres Project, headed by Lyndall Ryan and her team at the University of Newcastle, for example, gives locations, dates and other details of massacres of Indigenous Australians, with published sources. It lists more than 270 frontier massacres that occurred over a period of 140 years. Research on the Native Mounted Police and key campaigns of resistance across Australia, raises the possibility that the Aboriginal death toll may have been well over 60,000. The settler death toll is estimated to be at least 2,000.

These casualty figures come close to the total loss of Australian lives in the First World War. Other issues have been raised to question the definition of frontier violence as war. These include the lack of an official declaration of war, and a lack of formal military involvement from Australian infantry, artillery, or naval units. It is also said that fighting was sporadic and (at times) began as spontaneous conflict, rather than being organised and systematic.

John Heaviside Clark, Warriors of New South Wales (1813, hand coloured aquatint on paper).

Frontier violence was recognised as warfare at the time

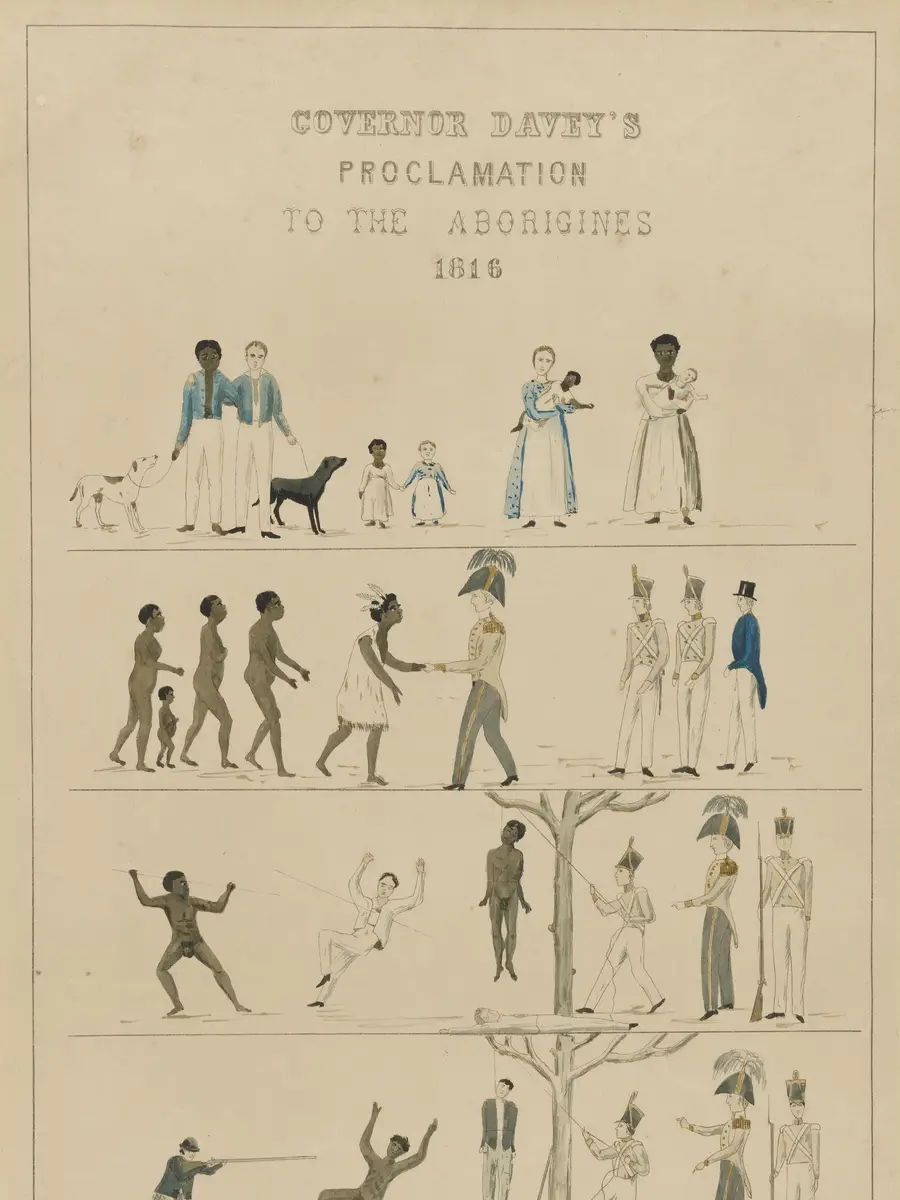

In 1825, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Earl Bathurst, informed New South Wales Governor Darling that he was authorised to “oppose force by force, and to repel such [Aboriginal] Aggressions in the same manner as if they proceeded from subjects of any accredited State”.

During the 1820s and 1830s, George Arthur, Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), referred to “the lawless warfare” and “our continuing warfare”. Newspaper editor Harden Melville reflected “during the months of September, October, and November [1830] … the black war, and nothing but the black war, was the subject of general attention.”

In Queensland in 1852, a newspaper editorial noted “the actual state of warfare”. In 1879, another Queensland newspaper declared, “we are today at open war with every tribe of wild blacks on the frontiers of settlement.”

Stephen Gapps’ Gudyurra relates, “Early to mid-1824 was the point when Wiradyuri groups came together and Elders gathered to hold what European observers had regularly noted in traditional conflicts as a ‘council of war’.” At a trial in early July 1824, magistrate William Cox argued that killing Aboriginal people in this area was justified because “the natives may now be called at war with the Europeans.”

Gapps’ The Sydney Wars notes, “I have been surprised how often journals and official records describe the early colony as being in a state of war, or how warfare raged across the Cumberland Plain and its fringes – despite the later histories that suggest otherwise.” Among the most notable examples, he relates “‘old-timers’ of the Hawkesbury–Nepean district in the late 19th Century often recalled the early 1800s as a period of ‘war’ against the ‘native blacks’. They even referred to those who fought as having ‘served in the war’.”

Changing ideas of war

Private William Joseph Punch was one of more than 1,000 Indigenous men who volunteered

for the First AIF. He died of illness on the Western Front.

Australian understandings of war have largely been defined by a long European history of formally declared wars waged between nation-states. War, typically, began when political leaders declared that it had begun, or through a stunning surprise attack with undeniable intent, such as the bombing of Pearl Harbor or the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

Though they are common in the public imagination, formal declarations of war are actually quite rare.

Australia has only formally declared war once: during the Second World War, Australia and New Zealand declared war on Finland, Hungary, Romania, Japan, Bulgaria, and Thailand. It is not obvious what common interests they might have had.

Australians have long considered war to be an ordered affair between states. Wars are expected to have declared beginnings, clear ends, and easily identifiable combatants. They are as much a legal and political state of affairs as a military one. “Rules of war” define the acceptable limits to organised violence, setting out who may kill, whom they are allowed to kill, and under what conditions. From this perspective, war is an abnormal condition, a temporary departure from normality. Peace is the norm, whereas war occurs as a problem to be solved, before peace resumes.

Both before and after the two world wars, however, war was often largely a matter of civil wars, insurgencies, and conflicts between colonisers and colonised. Certainly since the Cold War, less formal types of conflict within a country or region, unconstrained by legal or ethical frameworks, have become the norm.

Over the past 50 years, it has become painfully clear that civil wars, insurgencies, uprisings, revolutions and other conflicts that do not involve nation-states can be properly considered as war.

Recognition of Frontier Wars in works of Australian military history

Richard Broome’s chapter in Australia: Two Centuries of War and Peace (published by the Australian War Memorial in 1988) states, “since the 1970s it has been beyond dispute that a bloody frontier war moved across Australia for 160 years”, which is described as “the only full-scale war on Australian soil”.

Chris Coulthard-Clark includes 50 battles between Europeans and Indigenous Australians in Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia’s Battles (1998).

Jeffrey Grey’s A Military History of Australia (1999) argues that “the conflict between native inhabitants and white settlers over the possession and utilisation of land can readily be described as ‘war’.”

John Coates’ An Atlas of Australia’s Wars (2001) begins with frontier conflict and asks directly, “was this warfare?”, before answering in the affirmative.

John Connor, senior lecturer in history at the Australian Defence Force Academy, published The Australian Frontier Wars 1788–1838 in 2002: “Men with guns would fight men with spears far beyond 1838, and armed men on both sides killed unnumbered unarmed men, women and children. The Australian frontier wars would continue until the conquest was complete.”

David Horner’s Australia's Military History for Dummies (2010) “traces the story of Australia's involvement in war, from the colonial conflicts with the Indigenous population to involvement in controversial conflict in Afghanistan.”

Craig Stockings and John Connor’s edited collection Before the Anzac Dawn (2013) contains a chapter on the Australian Frontier Wars, written by Jonathan Richards.

Conservative historian Geoffrey Blainey suggested more than 40 years ago that “irregular warfare” between Indigenous and settler Australians be depicted in the Memorial’s galleries.

Sovereignty

Although our understanding of war has shifted throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the view of war as a formal, state-led conflict has contributed to lingering resistance to the idea of Indigenous–settler conflict being war.

Part of this scepticism comes from the fact that the sovereignty of Indigenous Australian nations was not recognised by the British, nor by subsequent colonial or Federal governments in Australia. Indigenous sovereignty was denied in order to justify British settlement in Australia: from the 1830s, Indigenous Australians were viewed by authorities as British subjects (rather than sovereign peoples). This meant that people could classify armed, warlike resistance to colonisation as criminal, rather than military.

Racial prejudice, based on now-outdated pseudo-scientific theories, also led some people to believe that Indigenous Australians were incapable of political or military organisation, meaning they were incapable of conducting warfare. According to this logic, even clear cases of organised, armed resistance against British colonisation could not be considered warfare. This assumption continued in the school system and in history writing until recently, contributing to a deep-rooted myth of the peaceful settlement of Australia.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, wars between coloniser and colonised were often played down in comparison with wars that were waged between European nation-states. According to British strategist Colonel Charles Callwell in 1896, these “small wars” lacked the imagined and imposed significance of the “real wars” between European states.

This division between small and real wars was often a matter of race and perspective. As Callwell notes, although “limited for the invader”, these small wars were “total for the invaded who had nowhere else to go.”

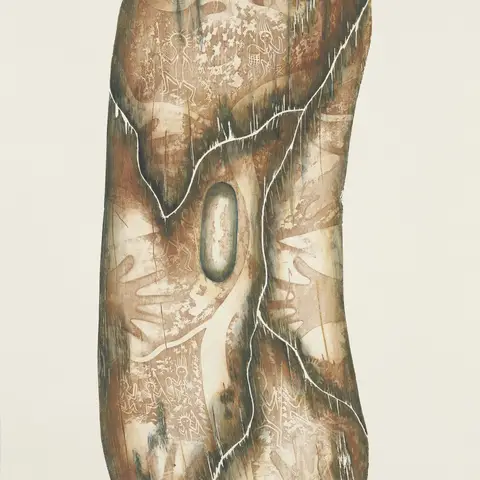

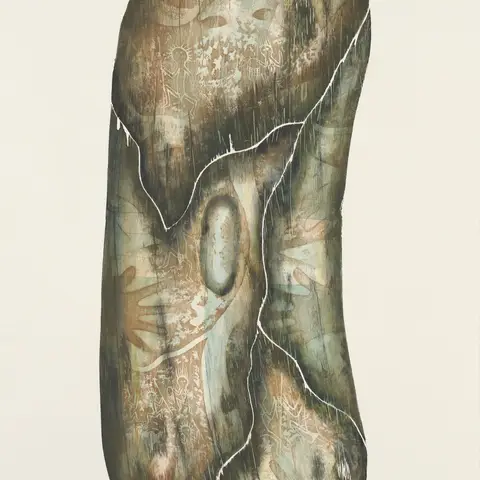

Paul Bong, Memories of oblivion 1 – 50,000 years of peace, 2016, hand coloured intaglio etching, 120 cm x 67 cm.

Paul Bong, Memories of oblivion 2 – Invasion day 1770–1788, 2016, hand coloured intaglio etching, 120 cm x 67 cm.

Paul Bong, Memories of oblivion 3 – cutting the heads off 1877, 2016, hand coloured intaglio etching, 120 cm x 67 cm.

Paul Bong, Memories of Oblivion 4 – cutting the feet off 1900, 2016, hand coloured intaglio etching, 120 cm x 67 cm.

Paul Bong, Memories of oblivion 5 – The Heart will live on 2000 – present, 2016, hand coloured intaglio etching, 120 cm x 67 cm.

There are many colonial conflicts that have been considered wars despite their small, sporadic, or uneven nature. Conflicts in India and parts of Africa, for example, were frequently discussed as military campaigns, and the British military leaders involved heralded as heroes. In the New Zealand Wars, the British recognised the military prowess of Māori even as they claimed victory; the war led to the creation of the first veterans’ homes and support systems in that country.

Debate about the nature of the Frontier Wars comes in part from the contradictory attitudes towards the conflict in newspaper articles, government reports, and historical writing and memoirs from the eighteen, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. As historian Jonathon Richards notes, “Early references in both colonial newspapers and official documents mentioned ‘war’, but some of the first published histories seemed intent on dismissing violence between colonisers and indigenous peoples as insignificant, something that only took place in other parts of the world.” While those who lived through the conflicts understood them as warfare, by the time histories of Australia were being written, the widespread myth that the settlement of Australia was peaceful meant that frontier violence was downplayed.

Staff Sergeant Robert Henry Reynolds, served in the New Zealand Wars in the 12th Regiment of Foot, British Army. He later settled in New South Wales.

Since the 1970s, however, historians have emphasised the warlike nature of the violence involved in the colonisation of Australia. As Australian historian Richard Broome noted in 1988, “To see Aboriginal–European conflict as war exposes the myth of the peaceful and lawful European penetration of Australia.” Despite the uncomfortable moral and ethical implications, Broome concludes, “in reality Aboriginal–European conflict was hostility between Britain and the various Aboriginal ‘nations’ … There was much ‘armed fighting’, making the conflicts truly wars.”

Today there is wide acceptance that conflict and violence between settlers and Indigenous Australians should be considered war. Historical research continues to highlight the sophisticated martial and political organisational structures of Indigenous Australian nations. Australian military historians have used the term “Frontier Wars” for decades; the Frontier Wars have been incorporated into larger studies of Australian military history in the work of David Horner, Jeffrey Grey, John Connor, Craig Wilcox, Chris Coulthard-Clark and John Coates.

For at least the past 25 years, Australian historians have largely been in agreement that the conflict between Indigenous Australians and settlers and agents of the colonial state was warfare, and should be described as such. War, despite the fact it is seemingly inseparable from human nature and history, has always proved difficult to define. Changing standards and laws, and the emergence of non-state political groups, have all forced changes in the ways we understand warfare. In the case of the Frontier Wars, it is less about updating definitions to fit a changing political climate, and more about revisiting what we thought we knew of the past, and viewing it in a different light.