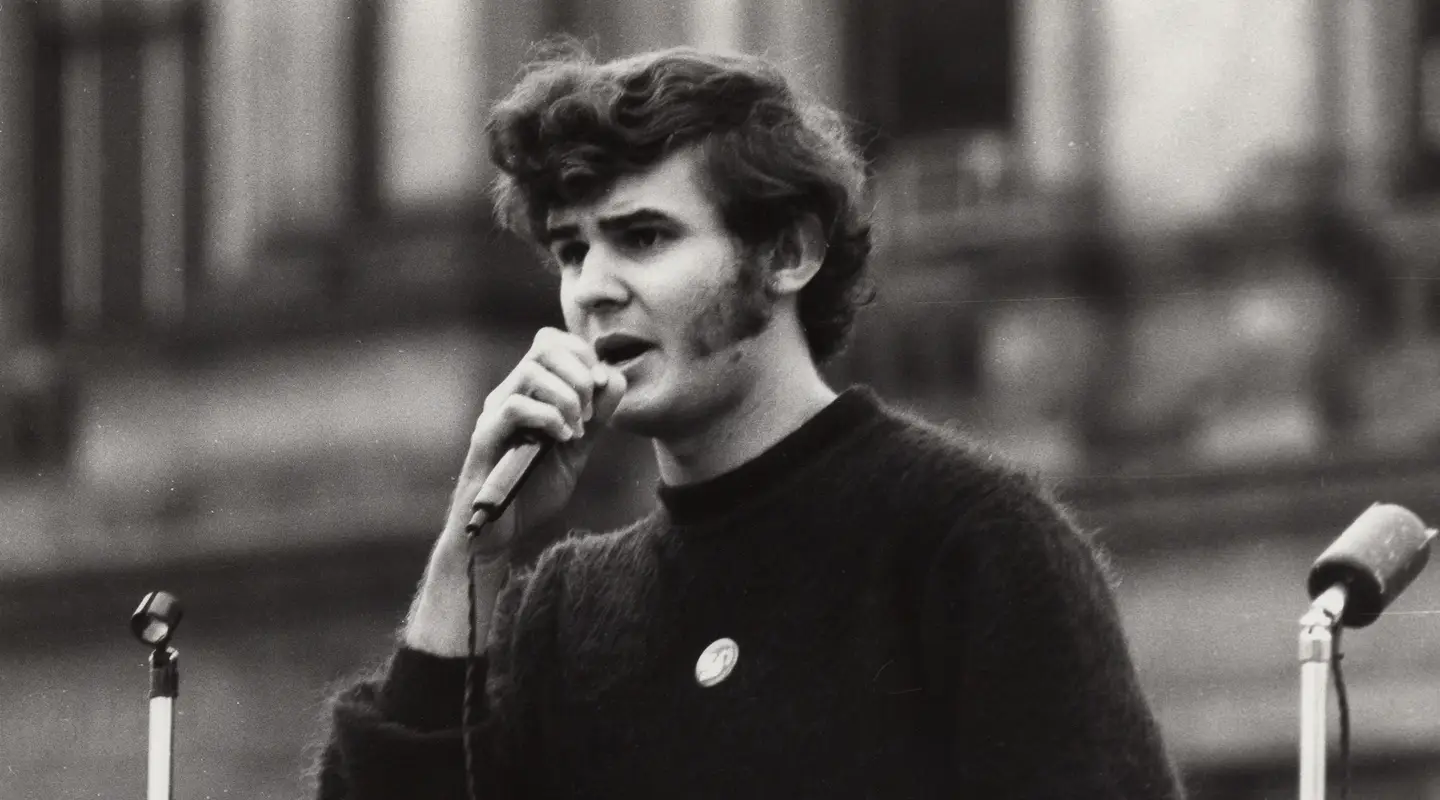

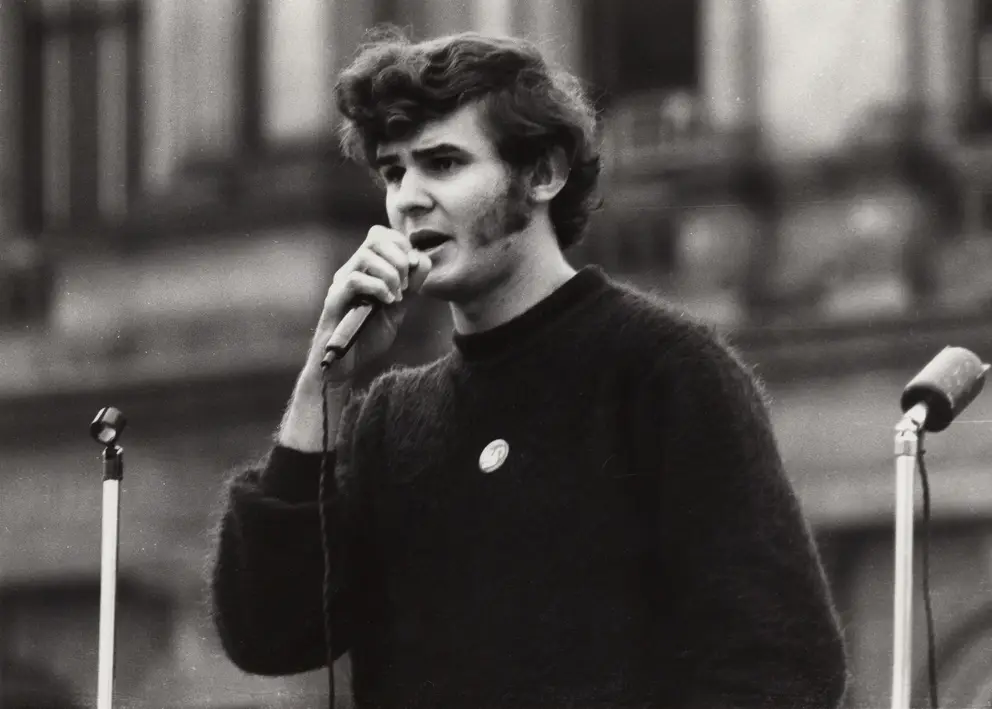

Lynn Arnold, Anti-Vietnam War Activist

For me, I think it was the six o'clock news where we were getting nightly reports about this growing conflict in Indochina. I found myself deeply troubled by what I was seeing. I didn't like the rhetoric that was coming out about this, I didn't like the messaging that was being said, and I felt wrong about the war.

Now, it was also at that time that the government announced they were going to introduce conscription, and I felt strongly opposed to that. So when I started university, I was very keen to get directly involved in the opposition to the war that was starting to happen around the country. At the time, our view very strongly was that this was a very cynical intervention by the government.

This was not one that was ideologically framed passionately. It was a case of all the way with LBJ, and we thought that was a deeply cynical response because Australian soldiers and Vietnamese soldiers and civilians were being killed for that simple cynical wanting to be on side with the big buddy.

It was something that we really cared about.

We actually wanted to see things happen, and so people were in that period giving up short periods of a year or whatever, a couple of years to the activity. But alongside of that, you did have these long-term activists who had been active in the peace movement since the 30s, and the Peace Pledge Union and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, and then later after 1965, the Save Our Sons movement, which was made up of women who had previously been active in other anti-war activities.

There was very much an idea of people power, that people could make a difference.

As we got reports from overseas of mass demonstrations happening in New York and San Francisco and other places, it was a real affirmation that lots of people could make a difference.

Ultimately, we would win the day, even though it would take some years. That was very much at the bedrock of what was happening, but not only just about the people power of those who had an opinion, but to actually tackle people's opinions who didn't have the same opinion as you.

We felt that the most effective thing we could do in trying to tackle government policy, to take on government policy on conscription and the war in Vietnam or later in Indochina, was to not only confront the government, but also to reach out there for public opinion.

When we had the first moratorium in South Australia in May 1970, we determined that we would letterbox every house in the metropolitan area, because we thought that it was going to be by those sorts of changes of opinion that the ballot box would ultimately be effective. That period of activism against the war taught me an enormous amount.

First of all, I learned mechanical things about how to give speeches, how to handle press conferences, how to handle opposition, how to chair meetings, how to organize campaigns, all of which would be enormously valuable. I suppose more importantly than that, I learned an enormous amount about the chemistry of the formation of policy and public opinion, the interaction of those with each other, how you really can achieve a great deal by swinging public opinion.

This isn't simply relying upon the silent majority, it's actually trying to talk about an informed public opinion.

That would really affect me later.

Later on, there would be some who would be angry at me for my having been involved in the anti-war movement and who would never want to support me. I didn't worry about that.

But what I did feel, I brought from that experience a lot more knowledge about the body politic in the wider sense. What it took me some years to really be appreciative of was the disparaging of those who went to war. I was never conscious of that at the time.

If anything, we didn't have a personal attitude towards the individual soldiers, the nashos and the volunteers. I really had no sense then of what it turned out later, I discovered was palpable, that return vets were having a terrible time. They were being ignored at best and disparaged at worst.

That was quite an eye-opener to me to learn of that years later because it wasn't them that we were fighting against. It wasn't them that we were asking the community to be against.

We were asking them to be against the government that sent them there.

Lynn Arnold was deeply disturbed by television coverage of the Vietnam War when he was still at high school.

Later, as a student at Adelaide University, he assumed a prominent role in campaigning against the war, collaborating with other activists from a diverse range of backgrounds and political positions.

The experience of this long campaign informed his subsequent career as a politician, including a term as Premier of South Australia in the early 1990s.

Accession: AWM2017.580.1.8

Lynn Arnold, Anti-Vietnam War Activist

Ripples of Wartime

Ripples of Wartime is a series of short interviews with Australians involved in and affected by the Vietnam War.

Filmed by Malcolm McKinnon for Brink Productions, they were made in association with the stage production Long Tan, which premiered in Adelaide in 2017.

Recording servicemen and servicewomen, conscripts and volunteers, families of those who served, anti-war activists and protestors, displaced people and post-war immigrants – the project truly reflects the complex and divisive nature of the Vietnam War.