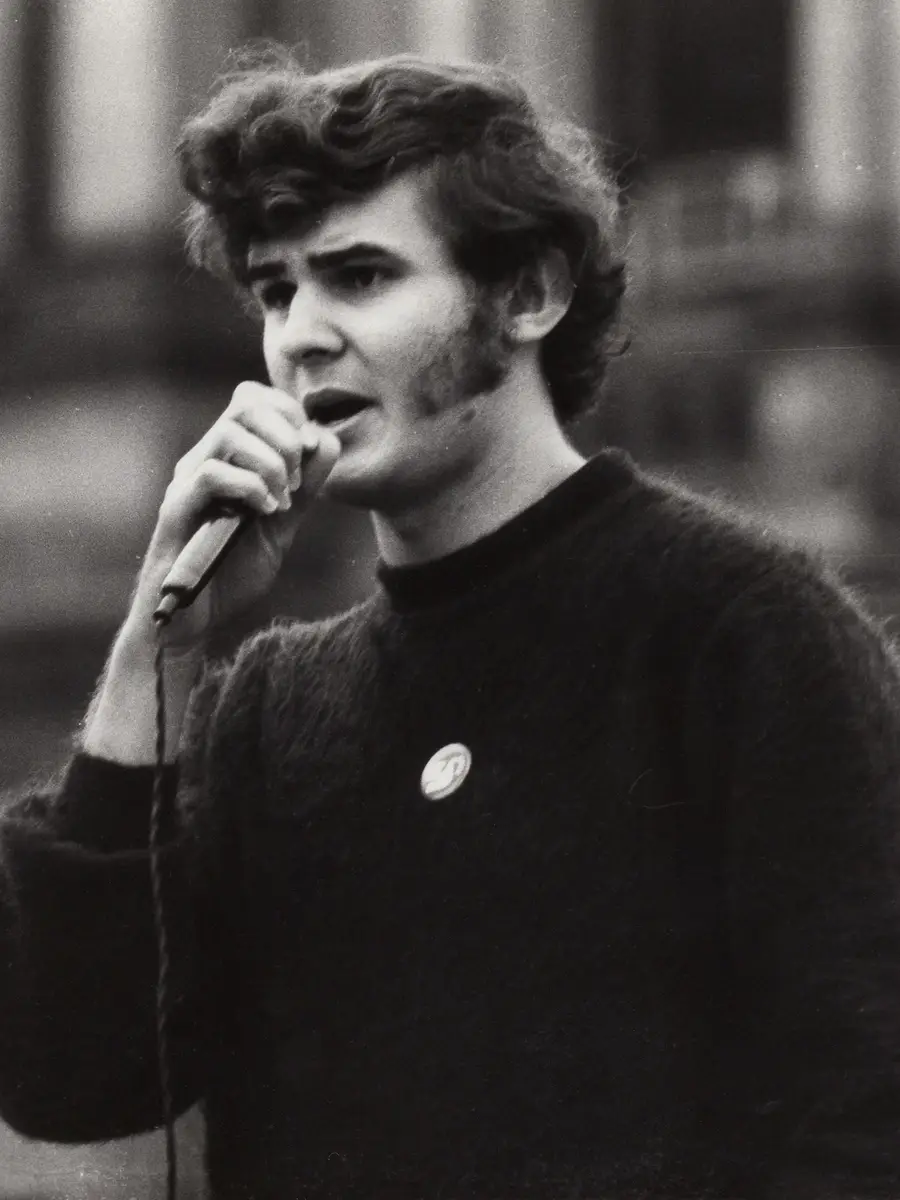

Trung Nghia Ton, Australian of Vietnamese descent

On my mother's side, they were North Vietnamese, and they fled south over the course of the war and set themselves up in South Vietnam. Ran a successful business, but about five years after the war ended, decided they wanted to flee.

My mum always tells me the story of, she was studying to be a lawyer, and she was in her third year of law school, and rode into school one day, and the whole university had been shut down, and the lecturer stood there and said, Go home. It's over. It's done. That's it.

And she ended up spending three or four years in limbo, and the businesses were starting to fail and had a lot of difficulties. And on my dad's side, it was the same. He was studying English to be a teacher, and then all the opportunities had sort of disappeared.

At the same time, there was this real friction with what the North Vietnamese had come and were starting to impose, because adapting to that was just—they couldn't do it. They would be tearing out a part of their personality or the hope that they had for the future, for their families. They couldn't see anything going forward, and they decided that they had to leave.

So they took a huge risk. A lot of people who left they knew were dying on the open seas, were being attacked by pirates, were disappearing or being caught and putting in re-education camps, but they decided that that risk was worth it and that's why they decided to leave.

I think that the sense of exile amongst the Vietnamese community is—it's pride in what we managed to salvage and bring over and fiercely defend from here, from wherever we are. I never really understood the sense of loss until one day my parents said, when we were in conversation, they said, we lost our country. You know, or in Vietnamese they say, mất nước, you lost. And nước is not just country, but everything about it, the culture and the sense of belonging.

That phrase, they don't drop all the time. They don't say it all the time, but certainly it came out once, and I understood it then, but really it just felt like we were still holding onto it here.Even though it doesn't exist in Vietnam, we still hold onto it quite fiercely in that generation.

For me, it's just having that historical context. I learnt the Vietnam War partly through the stories that my parents would tell. And again, a lot of the time it was rosy stories that emitted a lot of the suffering. But also, again, that's a real sense of pride. And then the other context that I learnt it from is really from the history books.

So a lot of it was from the Australian perspective, actually, an Australian military perspective, which I studied a lot. For me, having not experienced it, I can view it from that hindsight lens or from a different perspective. So for example, for my grandfather, he left his property. He left it. Someone else moved in and took it, but it was still his. He owned it.

And he, even now, after so many years, still thinks he can come back and claim it from the North Vietnamese government and he's sent petitions and everything. He's done a lot of work.

I remember when I went to Vietnam to visit the place, I was like, in my mind, I'm like, we're never going to get this back. It's a business, someone else's business on a street, on a country that you don't even have citizenship to anymore. You can visit, but you're not a North Vietnamese citizen, like, no one's going to recognise this and I knew that, but I had to keep that to myself because I knew for him that's still important.

The thing that I've learnt in my experience is that everyone suffered.

Everyone who participated in it, you know, in the real visceral way. Be it, you know, if you were a South Vietnamese soldier, a North Vietnamese soldier, a civilian, an Australian soldier, everyone is human and everyone who participated in it lost something and suffered something. And that, I think, really washes away all the other feelings of animosity when you realise an individual person was subjected to something that was really, you know, incomprehensible most of the time.

I meet, you know, Vietnam vets all the time. I work at the moment in a mental health hospital that has a lot of people that come through with PTSD and I look at what they go through and I look at what my parents go through and it's just, we're all human. We've just been put through something that's incredibly traumatic because of the circumstances and that's what it is.

I think, from a second generation point of view, the links that we draw between, say, Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War and our responsibility, therefore, to take refugees is pretty clear. And then the refugee intake that happened and that my parents were a part of seemed, you know, it was an obligation. I personally understand, you know, again from the stories of my parents, that they're human beings trying to find a sense of peace and security and they didn't want to leave their country.

They hung around for as long as they could and they took enormous risks. But in the end, that was the only option that they felt was available to them. So I understand that and then what's happening today is no different, really.

People are trying to do the best they can for their families and for their situation. So refugees that are coming out of, say, the Middle East, I certainly empathise with that situation. In terms of what our country is doing about it, I think our obligation between now and Vietnam is no different.

Particularly if we're involved in the conflict. I think that then we're, as a nation, both legally and ethically, we're responsible in some way. There's that great dilemma about, you know, are we going to swamp the country with immigrants? I think if you look past the rhetoric, you'll find that there's no evidence behind any of that and in fact the evidence is completely to the contrary.

That people that are fleeing and trying to make the best of their lives will come to a country and do their best that they can, with help, with a real sense that the community is rallying around them to just make the community better.

From my family's experience, that's what we went through and we identify ourselves as Australians because Australians let us do so. And that's now the identity that I hold very dear.

Trung Nghia Ton was born in Australia to parents who fled Vietnam after the war. His family has roots in various parts of Vietnam, although older members of his family now living in Australia have a keen sense of having ‘lost their country’.

Trung knows the Vietnam War from a distance, through stories told within his family and also through his own studies, often from an Australian military perspective.

Trung Nghia Ton works as a medical doctor and is also a member of the Australian Army Reserve.

Accession: AWM2017.580.1.12

Ripples of Wartime

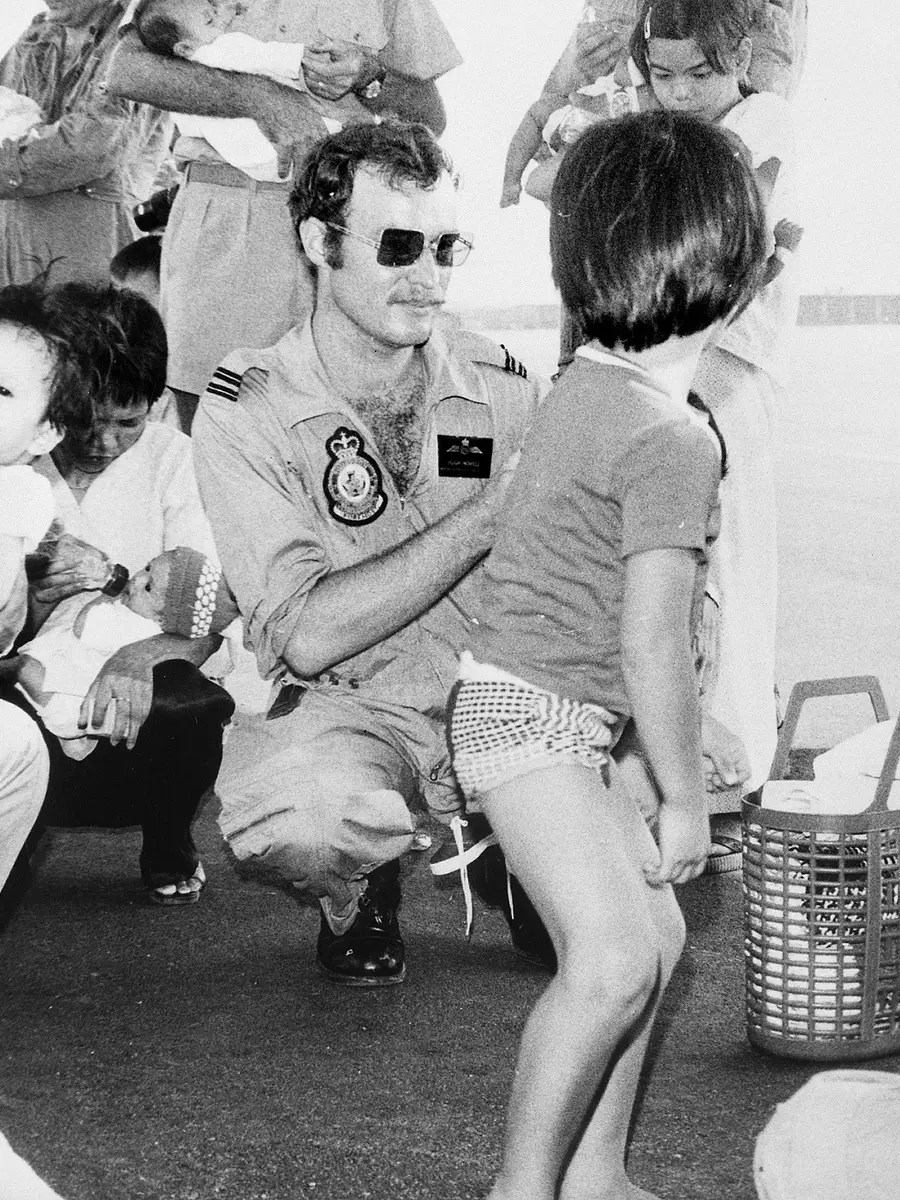

Ripples of Wartime is a series of short interviews with Australians involved in and affected by the Vietnam War.

Filmed by Malcolm McKinnon for Brink Productions, they were made in association with the stage production Long Tan, which premiered in Adelaide in 2017.

Recording servicemen and servicewomen, conscripts and volunteers, families of those who served, anti-war activists and protestors, displaced people and post-war immigrants – the project truly reflects the complex and divisive nature of the Vietnam War.