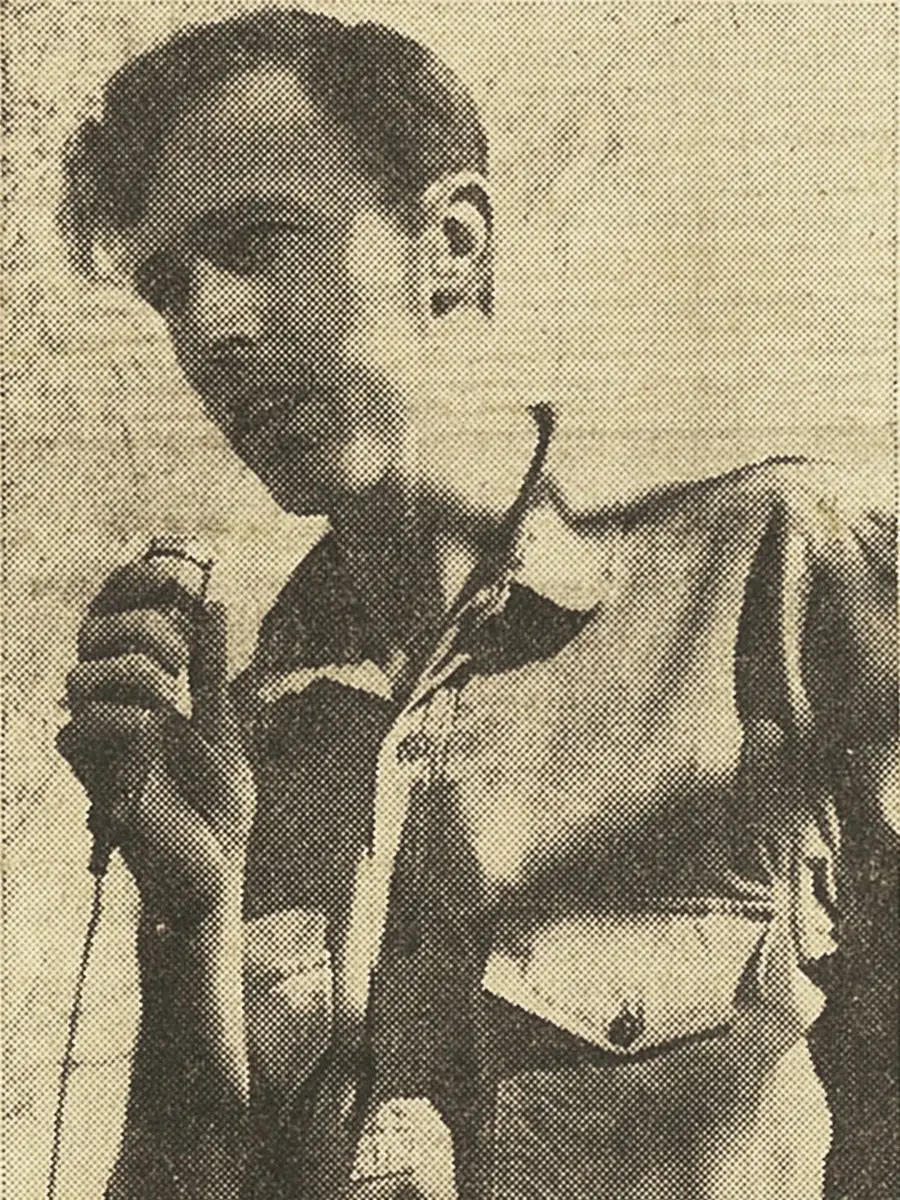

Di Fairhead, ADF Physiotherapist in Vietnam

When I saw in the April 1969 physio newsletter that they needed a physio in Vietnam urgently for 12 months, I thought, oh, I might just see what that's all about.

So I told my parents who of course thought I was stark raving mad, as did all of my friends. Why on earth would anyone volunteer to go to a war zone? I knew it was not a good place to be and it was a crazy war and all that sort of thing, but I also knew they needed a physio. When you're young, you do anything, so I did.

In the wards, there were some people would get pneumonia, that sort of thing, so I'd give them chest physio. Quite a few gunshot wounds where you'd have to get them walking properly and make sure that the muscles healed at the right length so that you'd, you know, massage around them and stretch and all that sort of thing.

The injuries were, I mean, they were horrific. The guys in intensive care, if they'd been survivors of mine incidents, they had really horrific injuries, but I'd been familiar with working in intensive cares. In Scotland, I'd been working in a burns unit and nothing could be much worse than that really.

So it was pretty horrific, but they were fit young men who were injured and the powers of recovery were just incredible and the fact that they might be in really bad shape, but they would always be asking how their mates were. I mean, that mateship thing really is there. They all did. It was just incredible.

It was just, I guess in a way, it was like arriving into a very big family because all of the staff were in the same boat. No one had any family up there.

We were our own family, so it was an amazing unit to work in.

It was okay for me getting letters from home, they were just chatty, my sister and family and friends, but some of the guys, they'd get letters from loved ones at home saying that they were involved in the moratoriums and anti-war things and they'd get really screwed up about it.

Why on earth are we here? We've been sent here, we're doing our best and then during that time, there was a strike when the unions wouldn't allow the (HMAS) Japarat to leave with even mail on. You know, there was a bit of ill feeling there.

It was a fantastic place to be, to be working, but it's a totally abnormal life. It's not something that you would choose to do for any great length of time unless you had something to get away from.

I know 365 days, I was very pleased to leave. You didn't let people know in the street that you'd been in Vietnam because why on earth would you go there? What were you doing there? My fairly lame reason that I was a physio, they needed a physio and I went there, was seen as being more than a little crazy.

I think it forced you just to not let people know that you'd actually been to Vietnam.

I can remember being really angry a lot of the time when people would say that they would be miserable about ridiculously petty things. I probably wasn't a very pleasant person. My friends, they'd say, how was it? Really all they wanted was one sentence.

Then they wanted to get on with what they'd been doing, having babies, moving, buying houses, that sort of thing. To a certain extent, I could understand them because they'd have no concept of what it was like there and I guess I wasn't about to give them any lectures on what it was like.

I think I was probably intolerant. I thought people ate too much. I thought they wanted too many things. They had too many material possessions that you didn't need.

Some of that's carried over for the rest of my life, I suppose, that really the only important things are to be well and have family and friends that you love and have them there. I think I got really cross because people fussed about irrelevancies.

I think if you can see how people survived, the Vietnamese people surviving in the dreadful conditions that they were living in and the soldiers surviving, I think to see that and to be part of it in any small way is a very life-enriching experience that I would never have wished I hadn't had.

Di Fairhead went to the Vietnam War as a physiotherapist in 1969, assisting the rehabilitation of injured Australian soldiers.

She remembers her tour of duty not just for the peculiar challenges of the military hospital but also for the intense camaraderie amongst members of her team and amongst the men she treated.

Accession: AWM2017.580.1.4

Ripples of Wartime

Ripples of Wartime is a series of short interviews with Australians involved in and affected by the Vietnam War.

Filmed by Malcolm McKinnon for Brink Productions, they were made in association with the stage production Long Tan, which premiered in Adelaide in 2017.

Recording servicemen and servicewomen, conscripts and volunteers, families of those who served, anti-war activists and protestors, displaced people and post-war immigrants – the project truly reflects the complex and divisive nature of the Vietnam War.