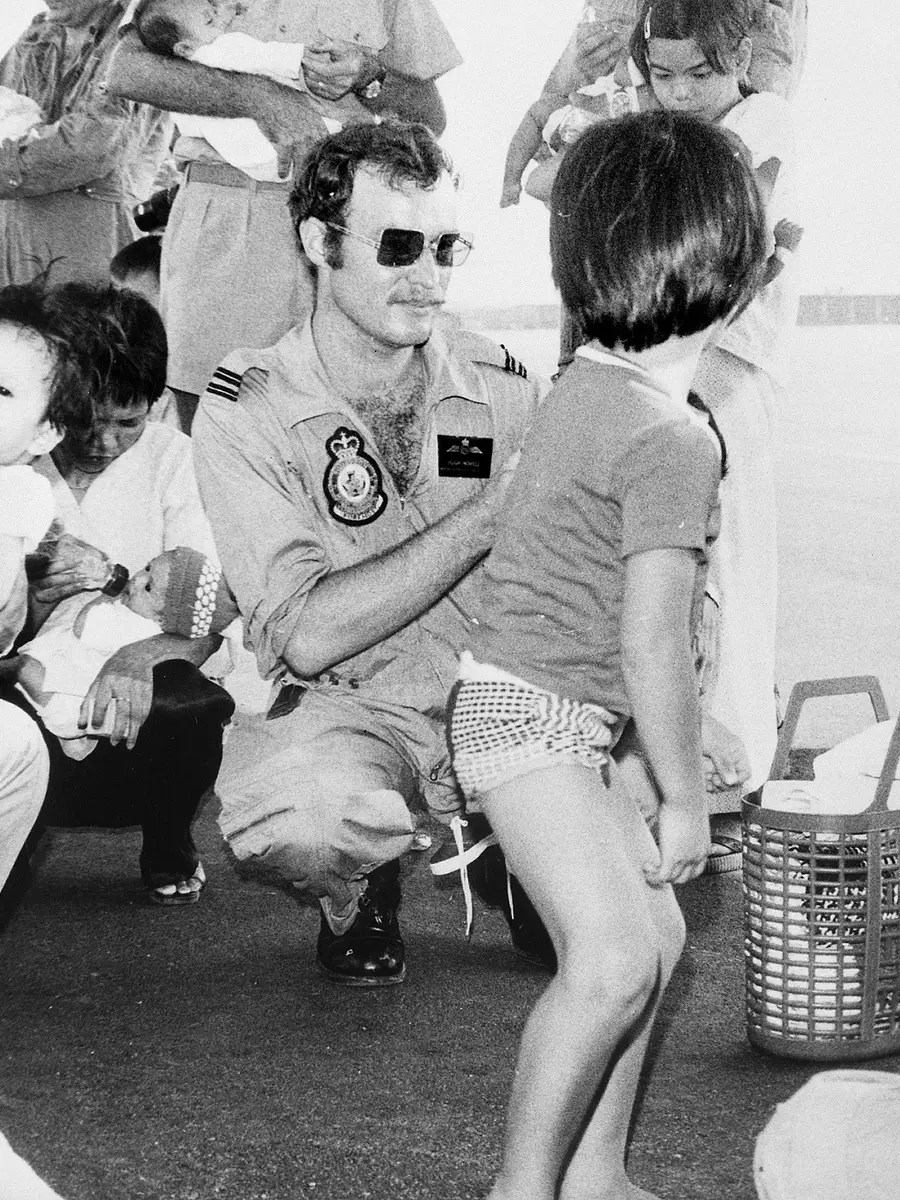

Neville Sinkinson, Vietnam War veteran

When the decision was made for our troops to go to Vietnam, I was all for it.

I volunteered to go, knowing that I would go. I was a firm believer in if there's going to be any trouble in the Asian countries, let it be over there, not closer to home.

That's how I looked at it. I guess the end result didn't come out that way, but at the time that's what I thought. And if there's trouble there, let us stop it up there and not here. I joined the Air Force to support Australia, and that's what I did.

The crew was four in a helicopter, two pilots up front, and a crewman and a gunner in the back. The crewman was always on the right-hand side at the back, because that had the winch on that side.

I believe an ambulance driver's just got the same type of job. Probably he doesn't get shot at, but that's about the only difference. You're there doing a job, you do it the best you can.

Without training, within a couple of days, just familiing with the areas, familiarisation with the weapons again, and all that type of stuff. I think it was in the first two weeks I had a rescue under fire with a winch operation and seeing a foot and a leg blown off doesn't do you wonders at all. But you say to yourself, well, that's what I came here for. Get on with it.

In a full year over there, I think the average time spent working over there was with nearly 300 days out of the whole year, actually on combat duties.

Well, I guess back in the past, the old wars, they went behind the lines for a few weeks, and then they'd come up again. But every day you went out was a day you didn't know what was going to happen. So you're on duty all the time, and at any time it could turn into hell, basically.

I think doing an extraction as a medevac or casevac, whichever, that someone's been wounded, perhaps on the ground, or he's been walked into a booby trap, a mine, anything like that, and you always know that there's going to be a problem. Possible legs missing, arms. And that wasn't such a good job.

You always wanted to get them guys out as quick as you could, and get them down to the hospital, and just hoping you could save their life. That used to cheer you up a fair bit when they were injured or wounded. Worse when they were killed, of course. It made you feel pretty ordinary. Probably angry. However, next day was another day.

Back into it again. And this went on for nearly 12 months, the pressure you were under all the time. And I think that's where it got you, after 12 months, you'd had enough.

The pressure was getting to you, and it was time to come home, hoping you could make it home in one piece. And I was lucky enough to do that. Unfortunately, some of the mates weren't, but that's what war's all about.

You'd been flying around all these many days, hours and hours and hours, and sorties galore. And all of a sudden, you've got your bags packed. And you're quick overnight, goodnight to the guys, and then you're on your way home, and it starts to become empty.

You're looking forward to getting home, but suddenly it doesn't seem right. I think one of the things that let me down the most was you're home, a few weeks later, suddenly you're organised to go on another exercise, an army exercise, which is not what you really want after a year of continuous work like that. No one says to you, how you're feeling or anything like that. That just didn't happen. Didn't happen at all.

So what, you've been to Vietnam? You'd be right, get on with it.

I had a lot of nightmares for a while. Probably when I came back, I had more nightmares than what I did when I was even over there at times. These things play in the back of your mind.

There Viet Cong are after you, or someone's chasing you, or what's going to happen tomorrow. That goes on for quite a bit. And you've got to sort through it.

If you don't, you suffer. It's a bonus to talk about it. And I think that is the downfall with the vets. They don't talk about it. And if you don't talk, you bury yourself.

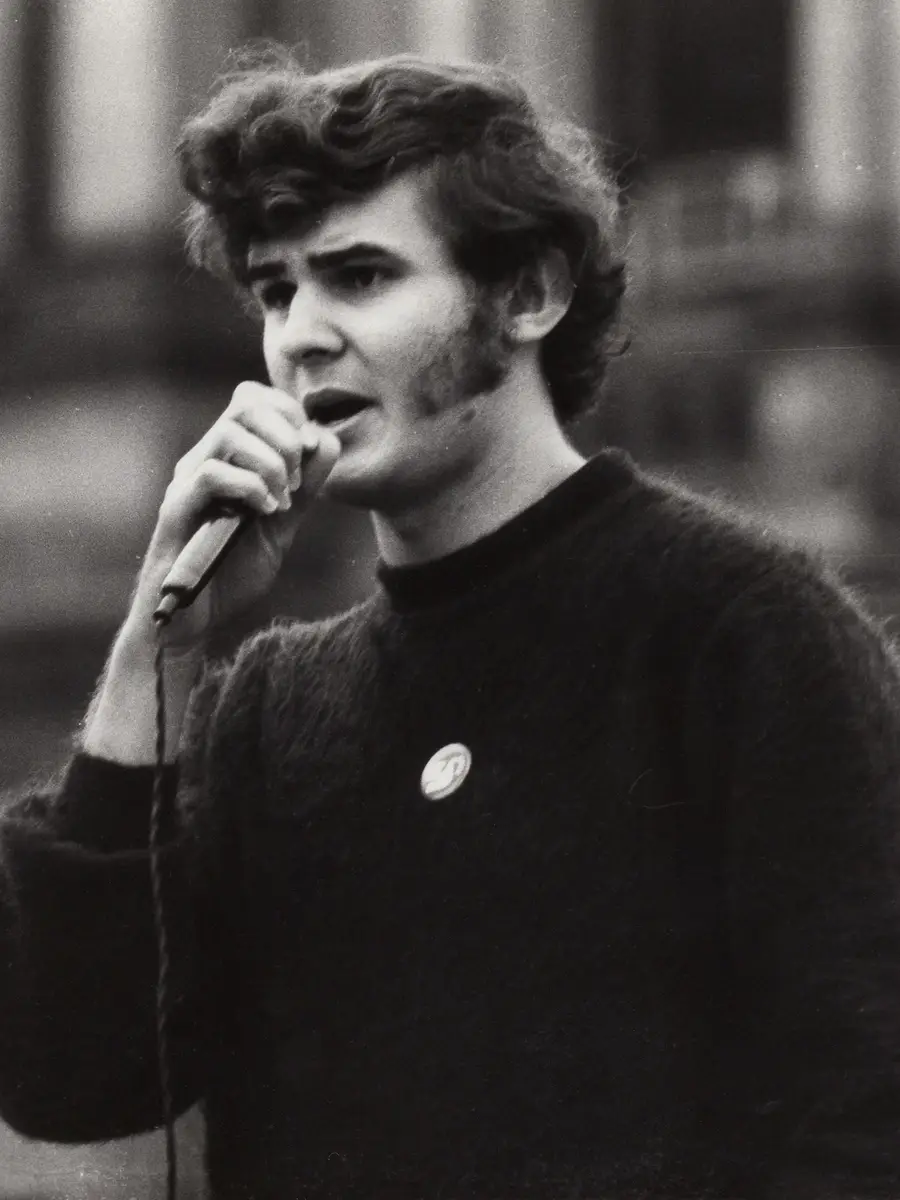

All the protestors at the time, that upset a lot of people. They certainly upset me at times. Protesting against war, sure, there's always protestors, but almost taking it out on the people that went there and I didn't like that.

And I've always thought a bit of an angry spot in there. But you're only doing what you're down to do. You get on and do it, whether a government, no matter who they are, sends you over there to fight. You do your best. You shouldn't be put down.

And I think we were a lot. No matter which way they go, you've got to be supported. It's the same with the war today.

The guys are over there doing a job. They've got to be supported. And if they can get the support and they come back and all the treatment, it makes it a lot easier.

We didn't have that at the time. It took a long time to sort that out.

For a while, you could pick any date and you knew on that date that your mate was killed or something went wrong.

These dates used to pop up quite often, but I don't think of them much now anymore. You never forget your mates or people, you know, incidents you've been in, you never do. They're always in the back of your mind, but you don't let it get you down. You think of it probably every Anzac Day, I do, and think of your mates you've lost and get on with it. It's how you survive.

Neville Sinkinson served in Vietnam as a RAAF helicopter crewman in 1970 and ‘71.

Working mainly in helicopter gunships, Neville was part of a team carrying ground troops in and out of operations, delivering ammunition and other supplies and evacuating wounded personnel, sometimes under enemy fire.

After returning home, Neville didn't feel how he expected:

The story of his Vietnam War experience is related in a book entitled Shockwave – An Australian Combat Helicopter Crew in Vietnam.

Accession: AWM2017.580.1.10

Ripples of Wartime

Ripples of Wartime is a series of short interviews with Australians involved in and affected by the Vietnam War.

Filmed by Malcolm McKinnon for Brink Productions, they were made in association with the stage production Long Tan, which premiered in Adelaide in 2017.

Recording servicemen and servicewomen, conscripts and volunteers, families of those who served, anti-war activists and protestors, displaced people and post-war immigrants – the project truly reflects the complex and divisive nature of the Vietnam War.