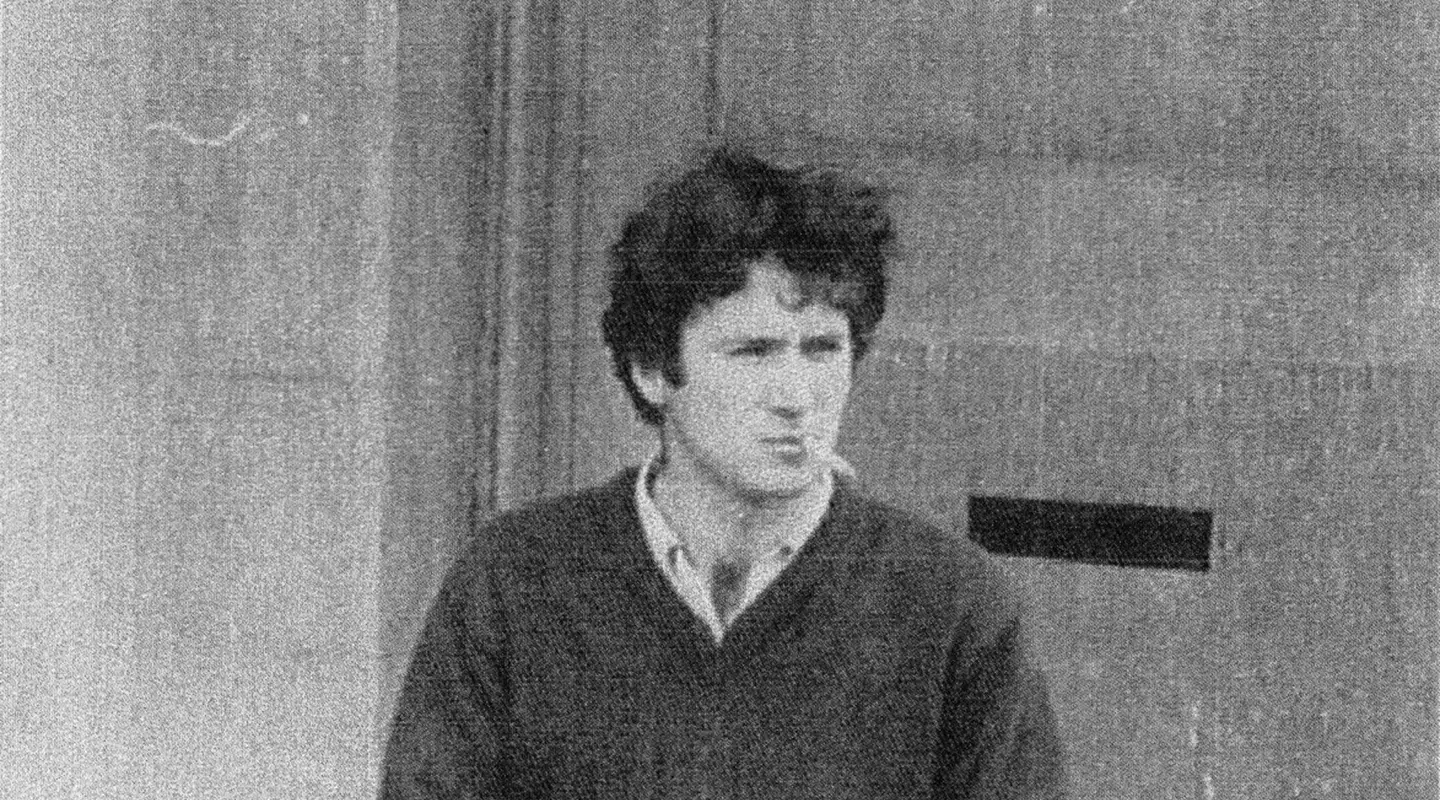

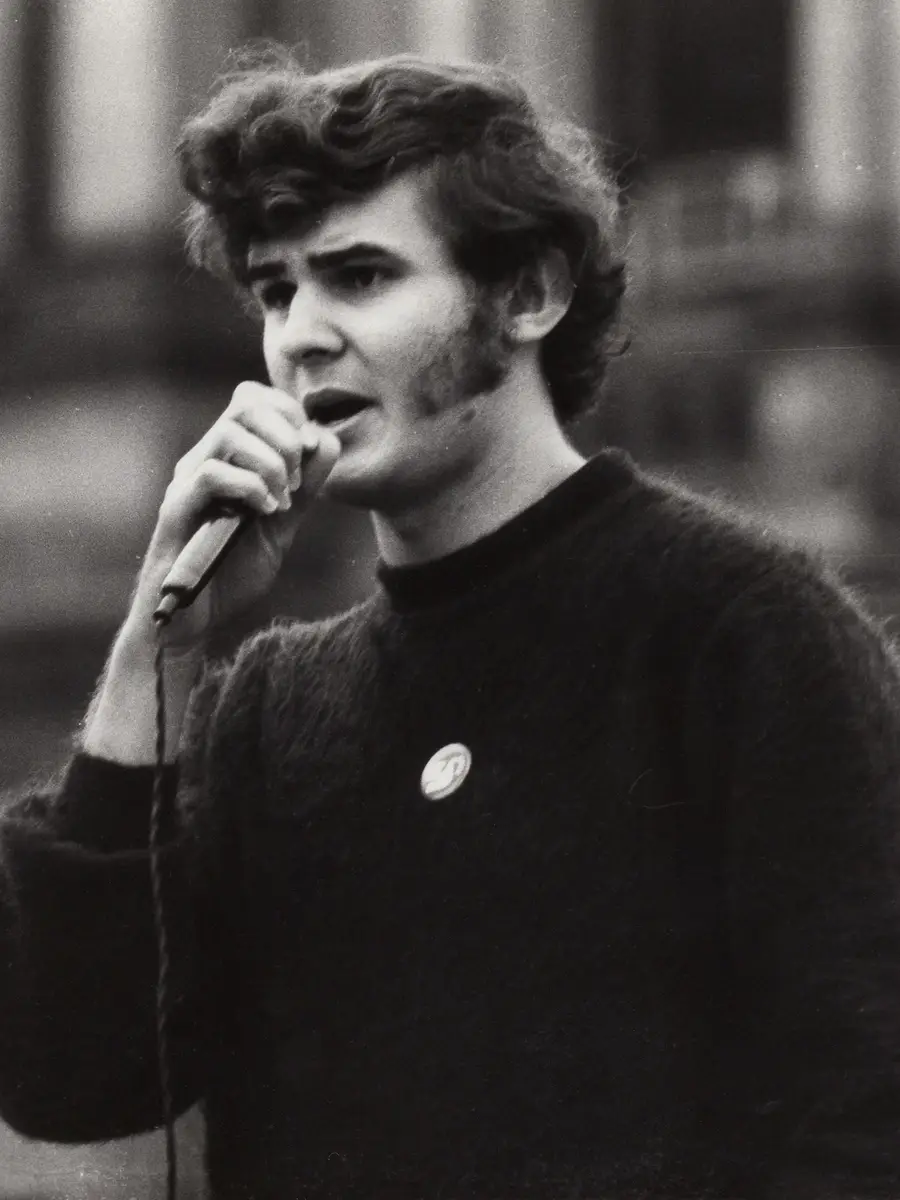

Des Files, Anti-Conscription Activist

And so I have an influence like that.

When I became aware of the government introducing conscription, which I felt was absolutely reprehensible.

It was really the compulsory acquisition of somebody’s life.

It was just forcing people into the Army.

So that’s how I started to evolve - thinking about it. A lot of people in my generation were just so angry about the bastardry of it all.

According to my ASIO file, in August 1965, I went along to a youth campaign against conscription meeting at the Unitarian Peace Memorial Church in Grey Street, East Melbourne.

And that was the formation of the youth campaign against conscription.

There were a lot of young people from churches and the YLA who formed that membership.

But what staggered me then when I read the ASIO file, was that somebody was there from ASIO watching us undertaking what was quite clearly, in my view, a democratic thing that we should be able to do.

We should be able to challenge government policy.

The ordinary man should have the perfect right to have their say in our society.

Otherwise why do we bloody go to wars for to fight for a freedom?

I got absorbed in all this with a, what I can only say is an idealism.

That’s what motivated me because like many of our generation, at a certain point you got to thinking not about the issues that government was putting forward but what sort of society were we going to be if we felt we could kill people in another country, bomb them, napalm them, you know, imprison them, shoot them as Viet Cong.

It became a moral issue.

There was an intensity, an anger about that period which motivated people to be wanting to do something about it, almost week in and week out.

I started campaigning in 1965, got the draft resistance movement up and running during ’68 and by ’69 I was emotionally, financially and physically exhausted because you did it all on your own energies and initiative.

But there certainly was an anger that made people constantly active.

People from all walks of life were starting to think ‘what’s going on here about this war?’.

So I could feel that there was change. The Americans for some reason allowed it to be televised and that turned a lot of people against the war because they just saw night after night this horror and it was such a contrast of what values you felt you had in society.

There’s something I learned from the anti-Vietnam years.

You realise that when a government makes a statement like the Menzies government did about sending Australian troops into Vietnam that it can be three or five people will make that statement within a government and that’ll get passed off as the truth and opinion makers in newspaper editors and television reporters will repeat that truth – in adverted commas - and it’ll do enormous damage.

People have lost their lives.

People have been ruined by 30 and 40 years by having gone to Vietnam as soldiers and having come back you know and their alcoholics or suicided or their family life’s been wrecked.

And it goes back to the way 3 or 4 people at the top of a government can make a decision and put it into effect and it is complete bullshit.

And that’s what I learned then, that you don’t take those positions as solid fact.

Des Files grew up in tough, working class suburbs of northern and inner Melbourne.

Initially influenced by his father and grandfather’s traumatic experience of earlier wars, he was deeply opposed to the conscription of young men of his own generation to fight in Vietnam.

Throughout much of the 1960s Des devoted considerable energy and resources to actively campaigning against the war in general and against conscription in particular, working alongside a diverse mix of other activists including the prominent Labor politician, Jim Cairns.

Ripples of Wartime

Ripples of Wartime is a series of short interviews with Australians involved in and affected by the Vietnam War.

Filmed by Malcolm McKinnon for Brink Productions, they were made in association with the stage production Long Tan, which premiered in Adelaide in 2017.

Recording servicemen and servicewomen, conscripts and volunteers, families of those who served, anti-war activists and protestors, displaced people and post-war immigrants – the project truly reflects the complex and divisive nature of the Vietnam War.