Poor sanitation on Gallipoli was a silent killer on the battlefield.

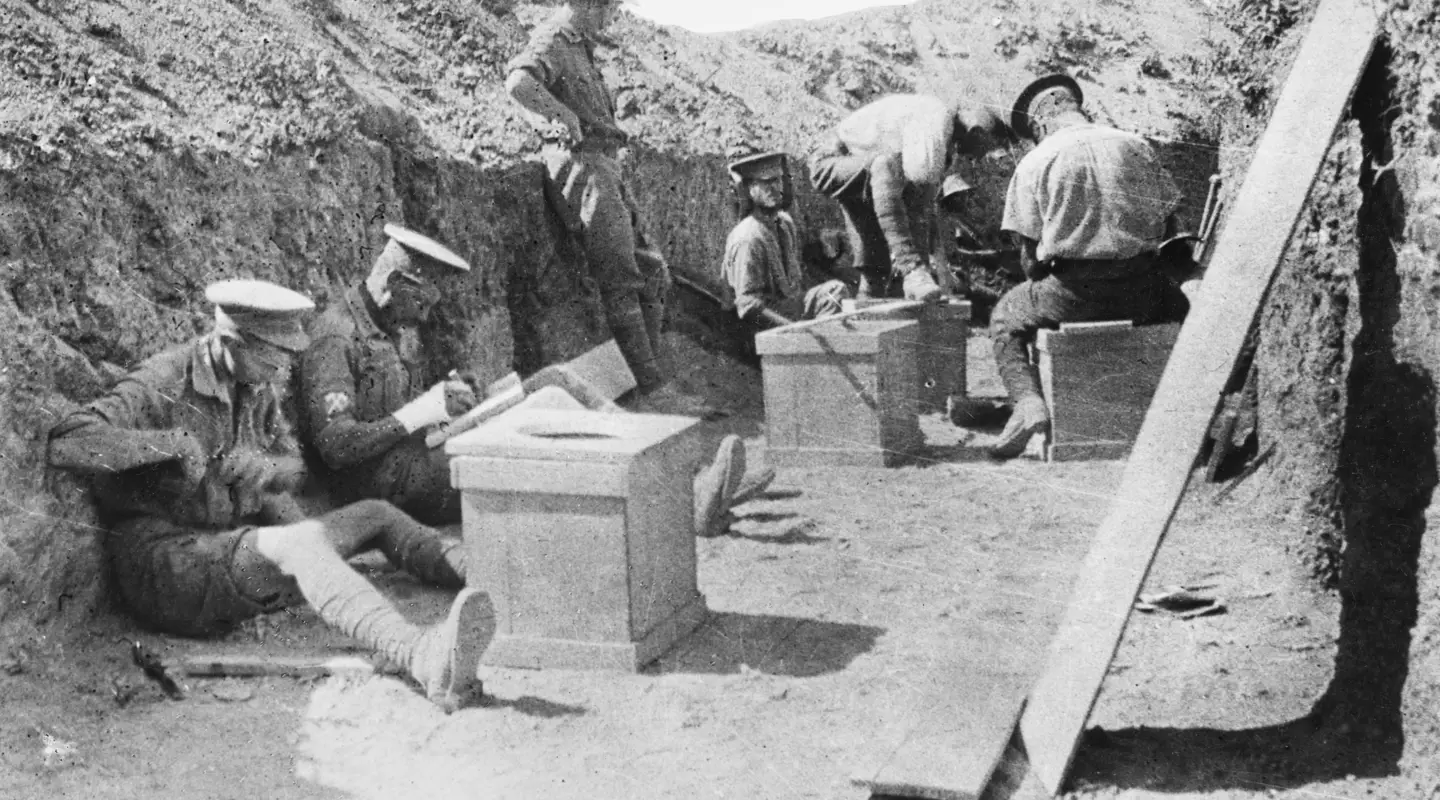

A thunderbox in a well-fortified trench, Gallipoli.

Poor sanitation had an enormous impact on casualties on Gallipoli as disease, particularly intestinal disorders, increased over the summer months. All refuse was supposed to be buried or burned, but because the smoke drew enemy fire, more often it was buried, though that was less effective. Deep pits, with a pole for the men to perch on, were recommended as more sanitary than shallow trench latrines, provided they were regularly covered with several inches of dry dirt to stop flies from breeding.

In early May 1915 a medical officer reported that there was “very little sickness” among the troops. But as the temperature rose, a steep increase in the number of flies, coupled with festering unburied bodies and limited water supplies for washing, led to outbreaks of diarrhoea and dysentery among the men. As the number of sick men increased, so the over-used pit toilets became harder to cover. Swarms of flies carried disease, landing on food and contaminating the unwashed mess tins.

Pioneers of the First Battalion building thunderboxes, August 1915.

Men in fighting positions, where it was impossible to dig pits, used “thunderbox” latrines. Few latrines at Anzac were not exposed to direct or indirect fire, and using facilities could be dangerous. With so many men cramped into such a small area, there was a complete lack of privacy; preserving dignity was a thing of the past.

Gunner Jack Findley, who served with the 4th Brigade on Gallipoli, recounts an incident with a thunderbox

I never got any decorations of any sort from that fight except one.

On Gallipoli ... me and a mate had to go and empty the general’s toilet.

And I lifted the can, put it on me shoulder and we went marching up the hillside and I found it were leaking all over my tunic.

So I was decorated for the rest of the stay there, because we had no water to wash it.

[partial] oral recording of John (Jack) Findley, 1980 AWM S03222

Listen to the full oral recording on the Memorial's website.