Hope in 25 words. The story of Private John Franklin and how letters carried his family's love through the war.

A few words from home can mean everything in wartime. For Private John Franklin, who was held captive by the Japanese in the Second World War, letters and telegrams from his family were a source of hope during his time in Singapore and Japan.

Eighty years later, these personal messages have been donated to the Australian War Memorial. The “Letters from Home” collection offers a glimpse into the bond that helped keep soldiers and their families connected during separation.

“These letters and telegrams offer an extraordinary insight into the love, loss and hope experienced by families separated during the Second World War. It brings us closer to the human cost of conflict,” said Memorial Director Matt Anderson.

"This is not just John’s story, it is universal and remarkable that they have been preserved for 80 years.

“These ‘Dear John’ letters speak to the heartbreak of any family with a loved one at war and the emotional lifeline that letters from home can provide. Telegrams of 25 words can mean the world.”

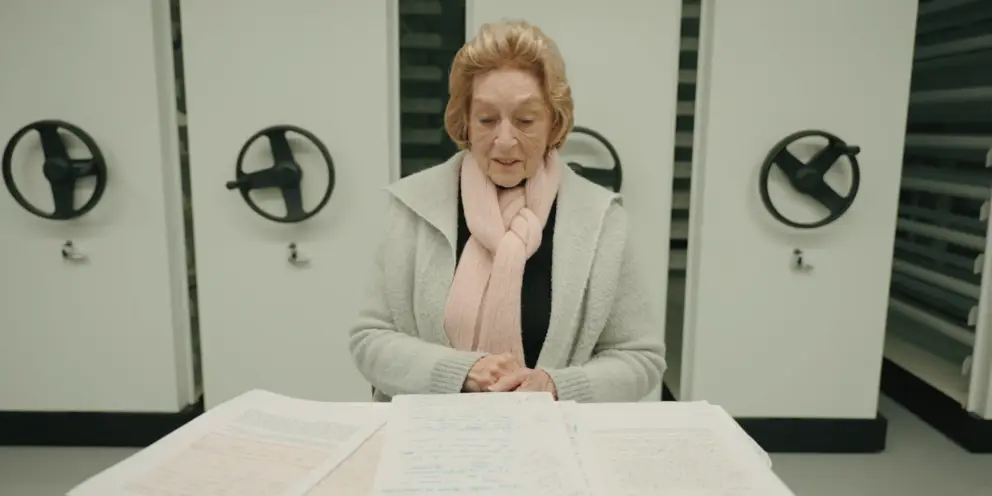

Rae Maree Curtis, 91, sits surrounded by an array of letters.

The heartbreak of separation

Among the letters in the collection, one stands out most. Dated 11 August 1942, this was the first letter John received during his imprisonment.

John’s niece, Rae Maree Curtis, donated the letters and said words from home offered both a lifeline and a look into the home front experience.

“John’s mother and father wrote these letters not knowing if their son was alive or dead,” Ms Curtis reflects. “Uncle John missed out on so much, such as birthdays and marriages, but I imagine it must have given him so much hope to hear about life in Australia.”

In 1943, the Japanese imposed restrictions on correspondence between prisoners of war and their families, allowing only 25 words per telegram. This limit was an attempt to diminish the morale among prisoners but it also made every word even more precious.

“Telegrams were the first tweets. In just 140 characters, John’s mother managed to say everything she could and reassured him that his brothers in Bondi and Artarmon were safe, his family in Worcester were unharmed, and that she and his father were sending loving thoughts.” said Ms Curtis.

John’s niece, Rae Maree Curtis, 91, studies a photograph of her uncle.

Rae Maree Curtis points out her uncle in a photograph.

A full circle story

By 22 August 1945, shortly after Japan’s surrender, John’s mother Minnie wrote a jubilant three-page letter celebrating his freedom.

"This collection tells a full circle story. Uncle John’s one letter, on his way home, is such a contrast to the 25-word messages," said Ms Curtis.

In his letter to his parents, he wrote:

“Believe me I feel as though I’ve been born and am starting life all over again. I feel pretty guilty for the worry I must have caused you, but everything is okay now. Don’t try and send money or anything but I’d give a fortune for a letter.”

The profound impact of receiving letters reflects the personal and emotional weight they carry. The “Letters from Home” collection captures not only the pain of separation but also the joy of reunion. It reminds us that history lives not just in battles but in the quiet moments of love and resilience shared between those on the front lines and those waiting at home.

They wrote for two years not knowing if he was dead or alive.

He didn't know they were writing.

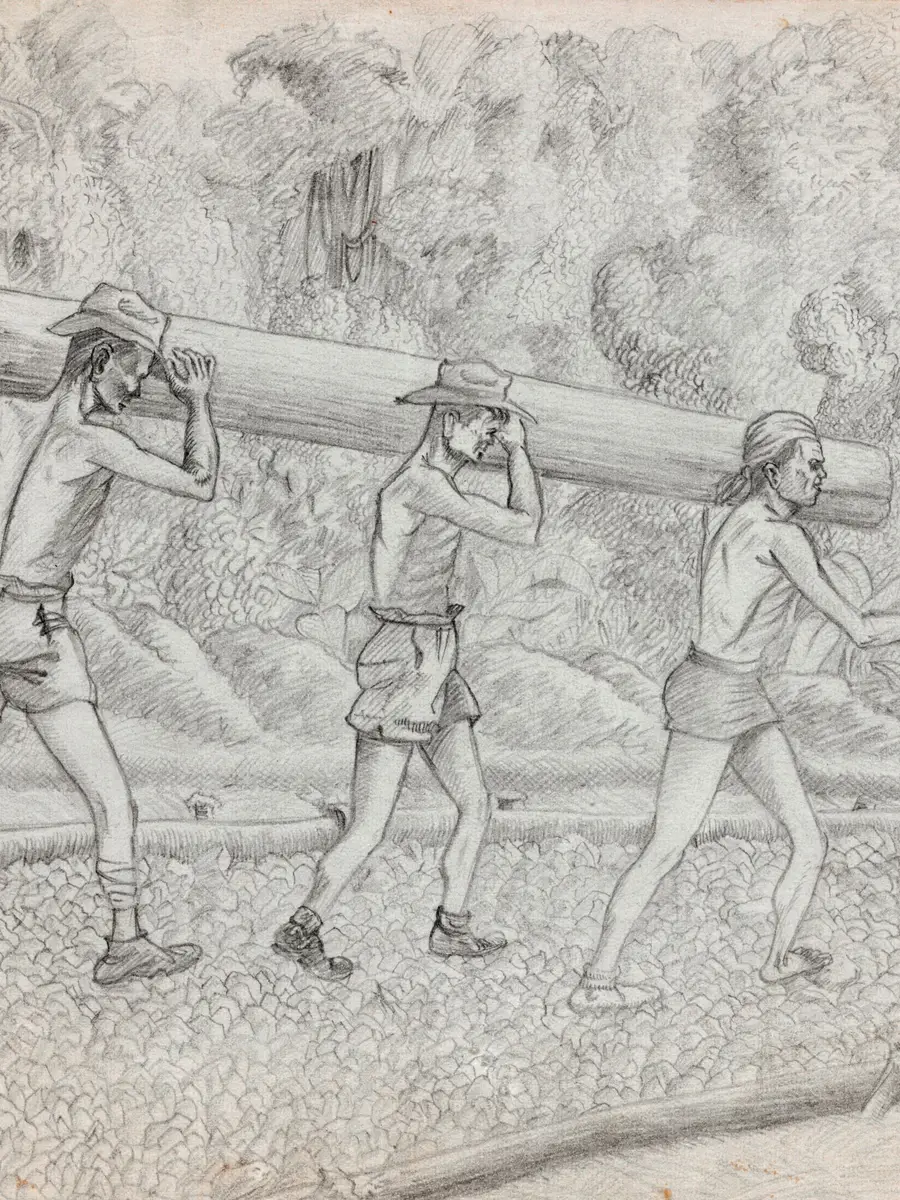

A collection of letters from a family to a prisoner at war.

Through these letters we don't just look at one family's experience of war.

These are representative of a nation at war.

Obviously the Japanese at that time weren't very open about sharing letters and getting postal services going between the POWs and those home.

For some POWs, maybe one or two letters throughout the three and a half years of captivity.

The family's attempt to maintain contact with John and let him know that they're still thinking of him, they love him so much and they can't wait for him to come home.

When you read the one from the mother and she says, "every time I'm knitting a pair of socks, I think of you", the love between all of us when we need to keep that connection, that family connection, it's so strong.

And right at the end of the war you could feel the jubilation in the letters as well, the just complete relief that he is coming home.

Well I am delighted that the letters are going to the War Memorial and this way we keep them for the future generations.

The reason they're coming into this collection is because they tell the nation's story.

I mean I almost feel when I when I read these letters that I'm eavesdropping.

I feel like these are intensely personal, intensely private.

And for the family to donate these to the nation on the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, we couldn't be more thankful.

This is the moment to pause, to remember, to celebrate this family, but to honour all who served Australia during the Second World War.

From me to you, just to remember today.