The censorship of servicemen’s mail during the Second World War put a gag on their relationships with loved ones.

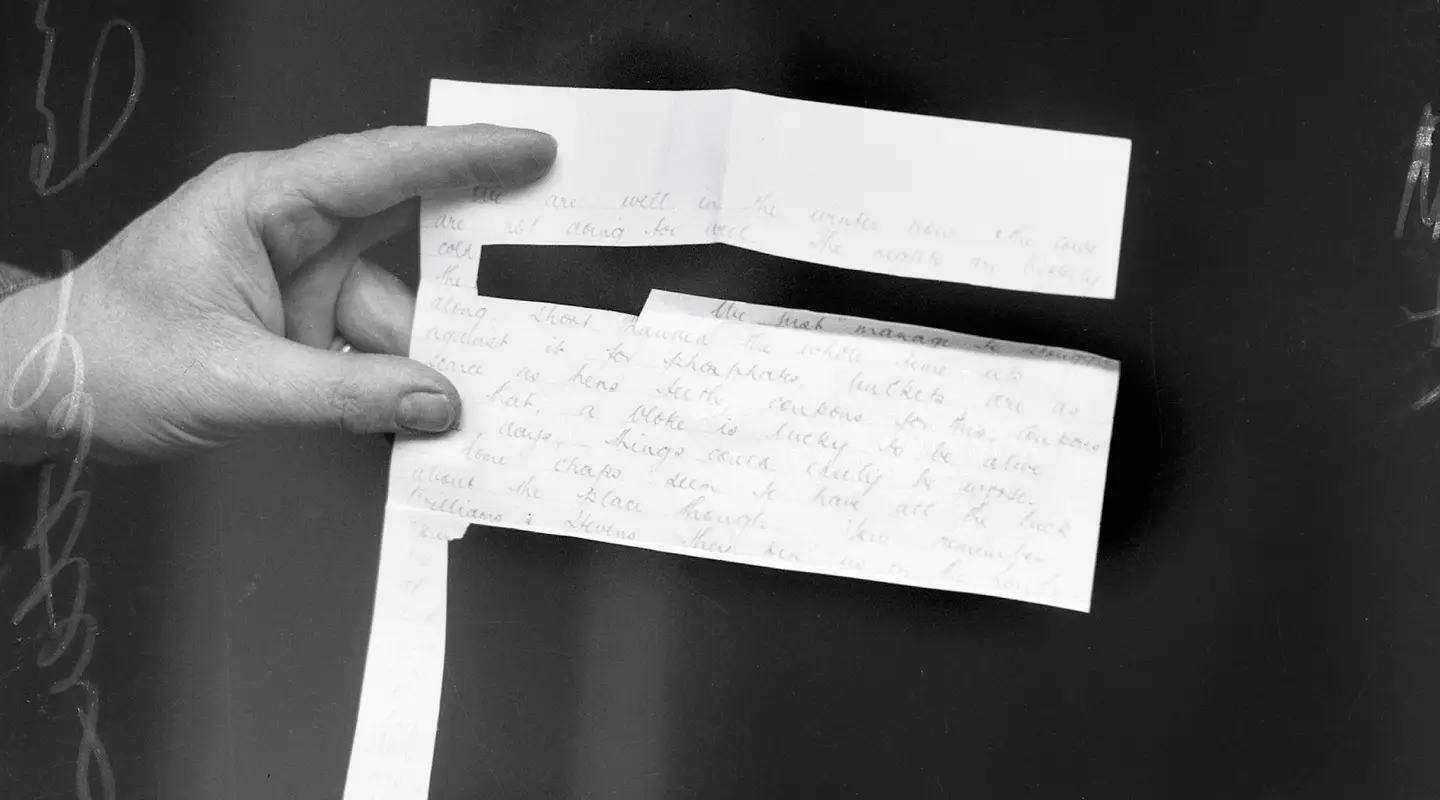

A page of an “indiscreet” letter after it was censored, Melbourne, 1943. Photographer: Melbourne Herald.

"I expect Babs darling that these pages shall suffer the fate of so many of my letters which I have written to you … the thought of other eyes – ‘censors’ – creates an attack of modesty, which proves my undoing ‘as much the destruction of your letter’,” wrote K Section Signals 17 Brigade Corporal Thomas Neeman to his wife Barbara in an undated letter from an unspecified location abroad. Neeman was not the only one to feel anxiety about the way field censorship inhibited how he wrote to loved ones during the war. Many servicemen and their families openly commented in their letters on the unique challenges that the presence of an outside observer brought to their main way of closing the distance and sustaining intimate connections.

Censorship presented an emotional barrier for couples: from the moment men enlisted in the military until they returned home, most of their grievances, their romantic and sexual fantasies, and descriptions of day-to-day experiences were no longer theirs to share with their partners alone. They were often frustrated by what seemed to be an assault on their privacy, and found ways to prevent their letters from being censored. Nonetheless, Australian servicemen had voluntarily enlisted in the military and generally recognised that revealing classified information could have serious consequences. When they attempted to evade censorship, they were trying to replicate the everyday intimacies that they had experienced in their pre-war relationships.

The primary roles of field censorship were to prevent military, economic, social and political information from reaching enemy forces, and to stifle the spread of anti-war and anti-Allied propaganda. The censors were looking out for information such as the number of troops in an area, casualty numbers, and battalion locations – and also for statements that criticised the military, the Australian government and the British Commonwealth. Preventing the spread of sensitive information was presented as justified because it promoted social cohesion and ensured that civilians were not discouraged from enlisting once the initial influx of recruitment slowed in April 1941.

Mentmore fountain pen with snakeskin.

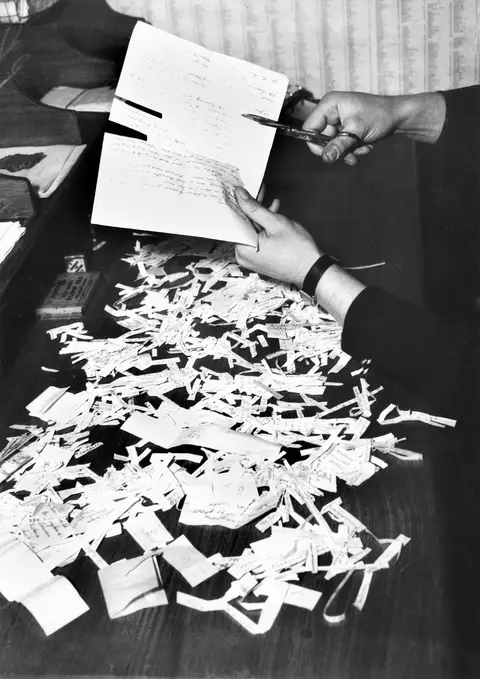

Ultimately, it was the responsibility of Australian military officials to enforce the censorship of private letters written between servicemen and civilians. The system worked similarly in all the armed forces. Officers, chaplains and medical practitioners were assigned to examine the correspondence being sent out by men in their company, while the civilian mail that was sent abroad was read by employees of local post offices. Field censors examined as many of the letters going out from their company as they could. If there was too much problematic content, the letter was returned to the writer to be rewritten; otherwise the censors removed this content by covering it with ink or cutting it out with a razor blade. Envelopes were then stamped to verify that the letters within had been “passed” by the censor. The design of this stamp was frequently altered to make forgery more difficult. To reduce the censors’ workloads, and to offer servicemen some semblance of privacy, every week each man was issued one “green envelope” which was not to be opened by the unit censor. To use these envelopes, the servicemen signed a certificate on the envelope which stipulated that “the contents of the envelope refer to nothing but private and family matters” and did not breach conventional guidelines. Nonetheless, green envelopes were still frequently examined at the writers’ base to ensure that they were not misused, with the result that their contents seldom differed from censored letters.

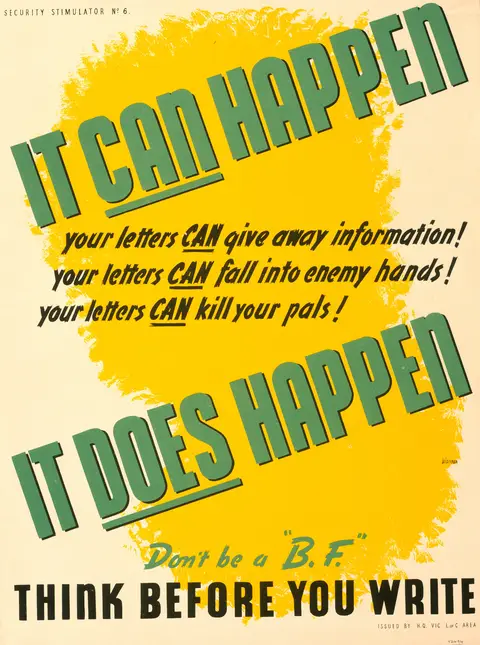

R. Malcolm Warner, It Can Happen, It Does Happen (1943, lithograph, 50 x 37 cm).

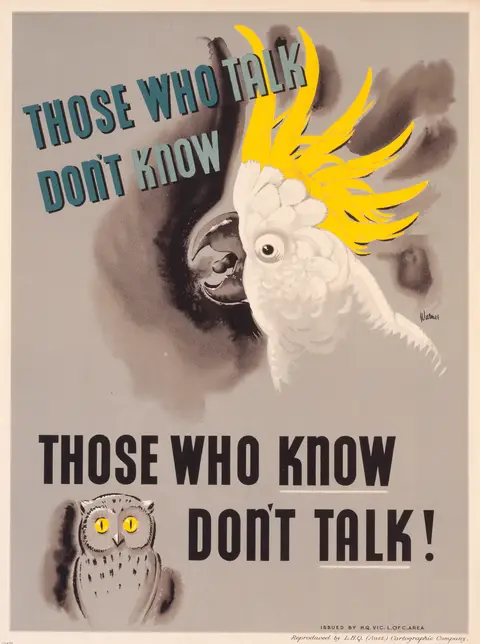

R. Malcolm Warner, Those Who Talk Don’t Know (1943, lithograph, 51 x 38 cm).

Under the eye

Several writers admitted in their letters that they were frustrated by how censorship rules were unclear or prevented the men in other ways from sharing vital information with their partners. For example, AIF 9th Field Ambulance Lance Corporal George Seagrove reflected bitterly to his wife Marjorie in July 1943 on the difficulties that he faced when writing letters home from New Guinea:

Topic of conversation is very boring, I know dear … now that you have told me my letters have been cut … I’m doubtful whether I can say much more then “Hello” to you. I have always been very particular about confining myself to things we have been told that we could mention so I can’t understand the censorship.

Mail censor cutting “indiscreet” material from a letter, Melbourne, 1943. Photographer: Melbourne Herald.

Similarly, in November 1941, while he was at sea, 2/13 Infantry Battalion Lieutenant Frank Bissaker mused over his excitement at seeing his wife Norma again so that he could “tell you all the things that the censor prevents me from relating at present.” A major gripe Frank had was that he could not write about what really happened, to ease Norma’s mind about rumours she had heard in the press about his battalion – including one which had claimed that the ship transporting them had sunk.

Knowing that external eyes were reading their letters made men worry about sharing personal and sensitive content that could be used against them by their superiors. 2/48 Battalion Staff Sergeant William Wiseman alluded to what other servicemen might think of his dedication to and feelings for Florence in a letter dated 23 December 1941. He wrote, “I don’t know what the officer thinks when he reads my letters they must sound like a moonstruck boy … but I don’t worry much about it and I don’t suppose he does either.” Naval officer Rowland Pullin and Field Ambulance Driver Seagrove said they were more bothered by censorship and its imposition on their relationships than Wiseman suggested.

Pullin refused to write a letter to his wife Ellie for several weeks when his mail was first censored while minesweeping on HMAS Swan in Twofold Bay on the New South Wales south coast. He wrote in December 1941, “I didn’t fancy any writing for somebody else to read it.” Eventually, Pullin got over his reluctance to write under censorship, although he admitted in September 1942 that it was difficult because he could not write much about his travels and felt that his “style is cramped by censors”. Seagrove wrote to Marjorie that although there were a lot of things he wanted to write in his letters, he hated to think that a censor might see his “sacred thoughts and perhaps [start] laughing about them.” He recalled an incident in which he had witnessed two officers reading out a letter and mocking the writer, and claimed that he wanted to “sock [them] fair on the chin.”

Lieutenant Thelma Long, Australian Women’s Army Service, censoring mail, Brisbane, October 1942. Photographer unknown.

Writers ensured that the censors realised that their presence in the exchange of letters was resented by addressing the censors directly. For example, Pullin declared that the censorship system “ran a gestapo agency” after a knife that he had asked Ellie to send never arrived. Irish WAAF Corporal Katharine McCall was most eager to attack the censors of her fiancée, RAAF 456 Squadron Leader Robert Cowper, knowing that her own letters would go under the razor. On 7 January 1943, she wrote bitterly from Ballyhalbert, Northern Ireland, “Yours written on the 1st came today. It was a lovely letter darling. At least, what I could read, as the censor really got cracking on it so much that there was hardly anything left. I guess you must have said something that you didn’t ought.” McCall suggested that in his next letter Cowper should again write about whatever had been removed, displaying a defiance of the censor’s authority. RAAF No. 80 Squadron Flight Lieutenant Harry Williams’s wife Helen used wit instead of anger to take on her censor in a letter from their home in Balwyn, when she cheekily finished with “Yours, my darling, with a kiss for the censor”. By offering a kiss, Helen emphasised that this letter was an intimate space for herself and Williams, which she believed was being invaded by the censor’s observation.

The censors themselves were in a unique position, as witnesses of personal discussions, which affected the way they handled their own relationships and built intimacy. Censors of low-ranking servicemen were usually officers in the same company, whose letters were in turn read by senior officers. For example, as an officer, Cowper was responsible for censoring his company’s correspondence. In April 1943, while he was serving in Malta, Cowper outlined how censoring letters made him feel self-conscious about what he wrote to his fiancée, McCall:

As Bob was so concerned about the perception that his writing was less romantic than his peers, it is possible that he and other censors borrowed touching statements from the letters of other men.

Evading censorship

For many writers, the pressure and frustration that censorship imposed on their relationships pushed them to find ways to prevent the censor from reading their messages or identifying problematic content. Most often, separated couples evaded censorship out of a desire to create a private space rather than to share prohibited information. Their methods included using civilian post offices while they were stationed in Australia, or getting a friend who was on leave to take their letters home. Seagrove successfully sent at least four uncensored letters to Marjorie between April 1943 and July 1944. He never specified in these letters the exact methods he had employed to evade censorship, although he implied that they were taken by another serviceman on leave and either posted through civilian channels or hand-delivered to Marjorie. In these four letters, Seagrove included some information that went against censorship, including his present movements; but he wrote more often that writing privately made him feel more comfortable to be sentimental and to describe his sexual fantasies. Aware in a letter of 8 June 1943 that his writing was more saucy than usual, Seagrove back-pedalled later: “Please don’t think that I’ve gone back to the stone age sweetheart but the chance to speak intimately with you is so rare that I must make the most of it.”

Wiseman devised an ingenious way of concealing short messages for his wife Florence by writing them under his postage stamps … he wrote “I Do Love You So Darling” under his stamp.

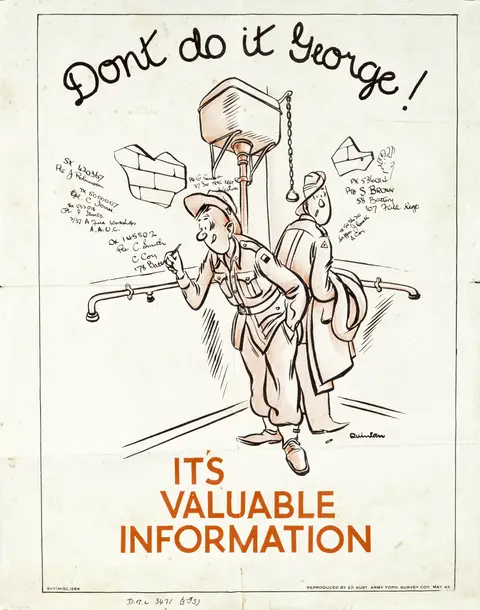

Hal Quinlan, Don’t Do It George, It’s Valuable Information (1943, photolithograph, 43 x 34 cm). A soldier writing his name, number, and unit on a toilet wall.

Once men were posted overseas, it made access to civilian post offices and peers who could deliver their letters increasingly difficult; so servicemen devised other ways of ensuring that what they wrote did not fall victim to the censor’s razor. Slang, codes and parables that only the recipient understood were sometimes adopted by servicemen and their loved ones to send cryptic messages. For example, V. H. Mattingly reported a case to The Daily News in March 1943 when a censor discovered that a serviceman’s seemingly innocent suggestion in letters to his mother to play a game of chess was actually an exchange of secret codes expressed by certain chess pieces or moves on the board.

Couples also found methods of hiding messages to each other. Wiseman devised an ingenious way of concealing short messages for his wife Florence by writing them under his postage stamps. For example, under the stamp on the envelope of his letter written on 9 March 1945, Wiseman wrote, “I would love to feel your hot lips on mine Darling and hold your body in my arms I love you passionately.” On 10 October 1943, he wrote “I Do Love You So Darling” under his stamp and on 19 November 1944 hid the note, “I Love You Sweetheart Passionately”. While most of his secret messages did not breach censorship, Wiseman used at least two of his stamps to disclose his location to Florence. Though he had found a way to get around the censor, most of Wiseman’s notes simply conveyed how much he loved Florence. Although he still wrote copiously about his love for her throughout his censored letters (and was never punished for doing so, beyond occasionally getting “mud slung” at him from peers), Wiseman was still determined to create a small space where he and Florence shared their feelings, away from prying eyes. Other servicemen and their partners probably employed this strategy, or adopted similar ones that successfully glided under the censor’s gaze.