At surrender ceremonies in 1945, Japanese leaders were made to do the unthinkable: surrender their swords.

On 11 March 1974, almost 29 years after the end of the Pacific War, Second Lieutenant Onoda Hiroo handed over his military sword to President Marcos of the Philippines at Malacañan Palace in Manila. First not knowing about the end of the war, and then not believing in it – Onoda, an intelligence officer educated at the Army spy school, the Nakano Gakkō – had been hiding in the mountains of Lupang Island, 150 kilometres southwest of Manila, and continued waging a guerilla war. After a series of failed attempts by the Japanese government to rescue him, on 9 March Onoda finally responded to the call of his former senior officer in the rescue team; then he was officially discharged from the defunct Imperial Japanese Army. Handing over his sword at the surrender ceremony in Manila symbolised an end to hostilities. For Onoda the war was over at last.

Made in 1413, this short sword was surrendered by Field Marshal Terauchi Hisaichi to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, who presented it to King George VI. RCIN 67300 Royal Collection Trust

Japanese swords have had a special status in Japanese society. In medieval Japan the swords were a symbol of the warrior class, and the pride of every samurai. In east Asia Japanese swords had been famous for their sharpness and toughness since the 11th century, when they took their present form with a slight curve, and became one of the commodities exported to China. The last samurai government, the Tokugawa Shogunate, enjoyed peace for more than 200 years from the mid-17th century. During this period, when swords were no longer in practical use (except for criminal acts, duels, executions and hara-kiri suicide), swords become the status symbol of samurai; as their aesthetic value became more emphasised, they were considered works of art. For samurai, it was a strict rule to wear a set of one long and one short sword when going outside their private residence. This samurai culture ended when political power was restored to the Emperor in 1868, and the new government strived for modernisation after the Western model; but the tradition of samurai carrying a sword survived in the modern military system. During the Pacific War, Japanese non-commissioned officers and warrant officers carried government-issued, mass-produced swords, which were not necessarily inferior to the older swords forged in the traditional way. Officers generally carried old swords that were fitting for their rank; some of the high-ranking officers carried centuries-oldine swords. Officers’ swords were part of military dress, and since they were not government-issued, they were the officers’ private possessions.

At war’s end

After Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied nations, many surrender ceremonies, large and small, were held in the Pacific and south-east Asia, where the Australian forces had been fighting. In most cases the ceremony included the ritual of the commander of the local Japanese force handing over his ceremonial sword to the Allied commander. (A notable exception is the surrender ceremony aboard USS Missouri on 2 September 1945, when the representatives of Japan signed the instrument of surrender in Tokyo Bay.) The highlight of the ceremony was the symbolic scene of handing over the sword, so many photographs were taken by official cameramen to capture the historic moment.

Including the sword ritual in a surrender ceremony may seem to be a natural act for the surrendering Japanese commanders, considering their samurai tradition. In fact, this unique custom was initiated by the Allied side. There was no precedent for the sword ritual earlier in the modern era, since Japanese forces had never attended a surrender ceremony as the defeated, only as victors; nor was there a precedent in ancient times. Furthermore, unconditional surrender meant the Japanese side was not in a position to make any request regarding the procedure that the ceremony might follow. The main purpose of including this ritual was to humiliate the Japanese commanders as the defeated side, and to take their swords as a token of surrender.

Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander of Southeast Asia Command (SEAC), was adamant that his counterpart, Field-Marshal Count Terauchi Hisaichi, the commander of the Southern Expeditionary Army Group, should hand over his sword personally. Mountbatten wanted to reverse the humiliation suffered by the British Empire at the fall of Singapore in 1942, and to restore the former imperial glory of Singapore; to this end, he had organised an extravagant ceremony at the Municipal Building for 12 September 1945. However, Terauchi was at his headquarters in Saigon and was too ill to attend the ceremony. So Mountbatten accepted the Japanese surrender from General Itagaki Seishirō, the commander of the 7th Area Army in Singapore, on Terauchi’s behalf. (Itagaki did not surrender his sword at this ceremony, but he and his senior officers, representing all the Japanese troops in Malaya, later surrendered their swords to Lieutenant General Frank Walter Messervy at a ceremony in Kuala Lumpur on 22 February 1946.)

Singapore, 12 September 1945. Coverage of the Japanese surrender to Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Mountbatten’s demand

But Mountbatten still wanted Terauchi to surrender personally and to hand over his sword to him. General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, was against Mountbatten’s wish, because Terauchi’s sword was a symbol of his authority over his forces. For the time being, Mountbatten needed to depend on Terauchi’s command to maintain law and order in the vast areas suddenly liberated by the Japanese surrender, where nationalist movements were emerging against the former colonial powers (see page 48). In spite of this, Mountbatten insisted Terauchi hand over his sword as a formal gesture of surrender. For Mountbatten, only this would make the surrender complete.

Knowing Mountbatten’s desire for his sword, Terauchi made a special arrangement to send an aircraft to Tokyo with an officer who could contact his family in Nagano and return with his sword. Terauchi surrendered to Mountbatten on 30 November at the rear of Government House in Saigon. The ceremony was on a much smaller scale than that in September, with only senior Allied officers present; this time Mountbatten did not want to expose the sick and old Terauchi to public humiliation. Terauchi presented to Mountbatten not one sword, but two – one long and the other short – in a box. Mountbatten kept the long sword for himself as a trophy of the war and presented the short sword to King George VI as a gift.

This short sword (now housed at Windsor Castle) was Terauchi’s centuries-old heirloom, a truly fine piece of art forged by Yasumitsu in 1413. Japanese officers’ ceremonial swords were usually antiques and were too precious for military use. After being confiscated, many of these fine swords were kept in museums and never used again. But Terauchi’s sword was used again in the most unexpected and absurd way. It was used on 20 November 1947 to cut the cake at the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip, to whom the sword had been given as a wedding present by his father-in-law, King George.

"In receiving your surrender I do not recognise you as an honourable and gallant foe."

General Sir Thomas Blamey

Aboard the Glory

Of course, it was heartbreaking for the Japanese commanders to part with their swords, the pride of their military career. Some commanders thought they could keep their swords, as they were their private possessions, and their only military use was solely ceremonial. General Imamura Hitoshi, commander of the 8th Area Army, attended the surrender ceremony presided over by Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, commander of the First Australian Army, aboard the carrier HMS Glory off Rabaul on 6 September 1945. He and 15 other Japanese delegates were carrying their swords. Imamura had earlier received from Imperial Headquarters the set of instructions regarding disarmament of the forces under their command, which included, “Officers should try to retain their swords and sabres.” Before signing the surrender document, Imamura dared to tell an interpreter that his sword was a symbol of his rank and authority and that he should retain his sword – at least for the time being, so that he could exercise control over the Japanese forces yet to be disarmed. However, Imamura was told by Sturdee to place his sword on the table in token of surrender. Imamura hesitated, but surrendered his sword after all. He may have thought that his sword would be returned, but he and other delegates left the Glory without them.

AT SEA OFF RABAUL, NEW BRITAIN. 1945-09-06. LIEUTENANT GENERAL V.A.H. STURDEE, GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING FIRST ARMY TALKING TO GENERAL H. IMAMURA, COMMANDER EIGHTH AREA ARMY, AT THE SURRENDER CEREMONY ON BOARD THE AIRCRAFT CARRIER HMS GLORY. THE SURRENDER OF ALL JAPANESE FORCES IN NEW GUINEA, NEW BRITAIN AND THE SOLOMONS, BY GENERAL H. IMAMURA, COMMANDER EIGHTH AREA ARMY, AND VICE ADMIRAL J. KUSAKA, COMMANDER SOUTHEAST AREA FLEET, WAS ACCEPTED BY LIEUTENANT GENERAL V.A.H. STURDEE, GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING FIRST ARMY.

Similar humiliation was felt by Rear Admiral Satō Shirō, commanding the 27th Base Force in Kairiru Island. Satō surrendered the naval forces under his command on Muschu and Kairiru Islands to Major General Horace Robertson, commanding the Australian 6th Division. The surrender ceremony took place on 10 September on the quarterdeck of an Australian Fairmile patrol vessel anchored at the ruined former seaplane base on Kairiru Island. Satō and his chief of staff were the only Japanese present, and the ceremony lasted less than five minutes. When instructed to hand over his sword by Robertson, he objected because the Emperor had not mentioned handing over the sword in the terms of surrender. Satō solemnly meditated for half a minute, as if muttering prayers for forgiveness to his ancestors, before complying with the order.

Significance

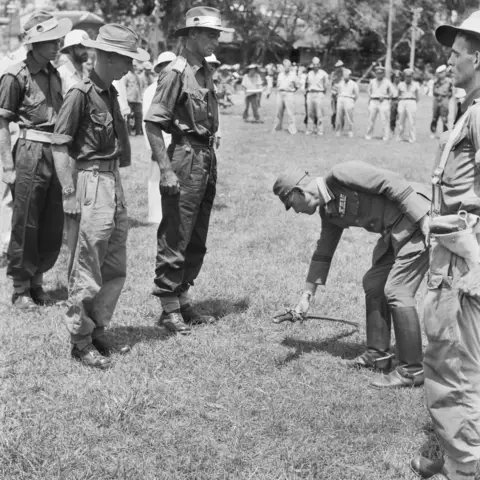

Handing over the sword was a gravely humiliating act for the Japanese commanders, but paradoxically, it was their only chance to show their proud samurai heritage amid the pageantry of public humiliation. Yet even this opportunity was not properly given to some of the Japanese commanders. General Sir Thomas Blamey, Commander-in-Chief of Australian Military Forces, who signed the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on behalf of Australia at Japan’s formal surrender in Tokyo Bay on 2 September, accepted the surrender of Lieutenant General Teshima Fusatarō, commanding the 2nd Army, at Morotai on 9 September. The ceremony was held at the 1st Australian Corps’ sports ground, packed with representatives from all the Australian services, and some members of the forces of the US, Netherlands East Indies and India. The sword was handed over before the signing – but strangely, though many photographers, official and unofficial, attended to capture the historic moment, there is no photograph.

Only one film captures a brief scene of a sword being handed over very curtly before the signing. The highlight of the ceremony is probably Blamey’s speech to the huge crowd after the signing, which includes this stern warning at the end:

In receiving your surrender I do not recognise you as an honourable and gallant foe, but you will be treated with due but severe courtesy in all matters. I recall the treacherous attack upon our ally, China, in 1937. I recall the treacherous attack made upon the British Empire and upon the United States of America in December 1941, at a time when your authorities were making the pretence of ensuring peace between us. I recall the atrocities inflicted upon our nationals as prisoners of war and internees, designed to reduce them by punishment and starvation to slavery. In the light of these evils I will enforce most rigorously all orders issued to you, so let there be no delay or hesitation in their fulfilment at your peril.

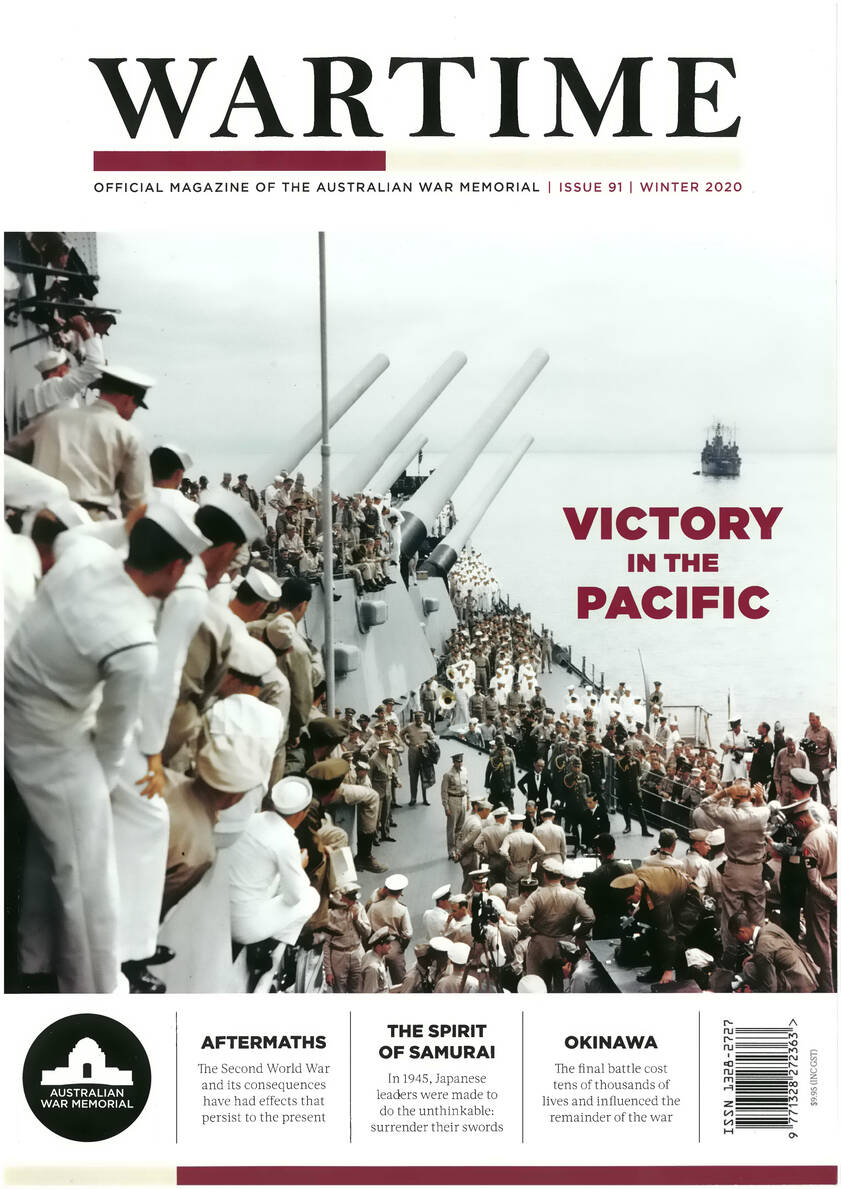

On 2 September 1945 the instrument of surrender on the USS Missouri.

Blamey, knowing the many atrocities committed by the Japanese troops and their ill-treatment of Allied prisoners of war, did not have any room for sympathy. However, an article in The West Australian acknowledged Teshima and the accompanying officers’ fine demeanour amid the intense public humiliation:

In due fairness, it must be said, however, that Lt-General Teshima conducted himself with the greatest dignity throughout and so did the other senior Japanese officers with him.

Major General Uno Michio surrendered his troops, part of the 37th Army, in Bandjermasin, Borneo, to Lieutenant Colonel Murray Robson, commanding 2/31 Battalion, on 17 September. The ceremony was held at a soccer field; Robson, who had lost many of his men in New Guinea and Borneo, ordered Uno to place his sword on the ground. It was a deliberate insult to Uno’s honour, witnessed by hundreds of Japanese servicemen among the crowd of Australian troops and local spectators. Uno refused the order, and Robson told him again to lay down the sword. Uno refused again. A young interpreter, Arthur Papadopoulos, who had grown up in Japan, had to act quickly. Afraid that shame could drive Uno to use the sword in a suicidal attack, Papadopoulos, fluent in Japanese, spoke one word: junshi. In the ancient warrior society it meant “to kill oneself after one’s master’s death” and implies absolute loyalty. In this case the word meant “to surrender following the Emperor’s surrender, leaving personal humiliation behind”. After hearing this single word, Uno laid down his sword.

Major General Uno lays his sword at the feet of Lieutenant Colonel Ewan Murray Robson, Commanding Officer, 2/31 Infantry Battalion in Borneo, 17 September 1945.

118033

The sword ceremony took place even in Japanese prisoner of war camps outside and inside Japan. In the Notogawa Branch of Osaka Camp, the camp commander, Second Lieutenant Nakanishi Yoshio, handed his sword to an Australian prisoner of war, Lieutenant Keith Goddard.

The Notogawa Branch, located south of Lake Biwa in Shiga Prefecture, was opened on 18 May 1945 and held 301 prisoners of war, including 55 Australians. The prisoners were mainly used as agricultural labour; and although they suffered ill-treatment, malnutrition and awful hygiene, there was no danger from Allied bombing, and none of them died. In 1945 systematic bombing raids by American B-29s on military facilities and industrial cities on Japan’s main islands were intensifying.

In May Germany, Japan’s ally, had surrendered to the Allied nations. To most of the Japanese, although they did not say so, it was obvious that Japan was losing the war. They had lost their loved ones, endured food shortages, feared bombings, and above all felt suffocated living under the oppressive military regime, and they longed for the end of war. Now the war was over. Nakanishi surrendered his sword, the spirit of samurai, which was no longer needed for the peaceful new age.